Rebirth of the Wiscasset, Waterville, and Farmington Railway

On June 15, 1933 the southbound train of the Wiscasset, Waterville, and Farmington Railway (WW&F) jumped the track in Whitefield, Maine. The locomotive nosed down an embankment towards the Sheepscot River, coming to rest just feet from the water’s edge. Although the WW&F had been resurrected from near-closure on at least two other occasions, this time it was not to be. The WW&F was closed for good. Following closure, the railway’s mainline was scrapped to satisfy the creditors, and equipment was either scrapped or sold. While the railway faded from the daily lives of residents in the Sheepscot Valley, it would live on in their memory. Well remembered especially by children, like Harry Percival, who grew up along the right-of-way. For them, the railway was a playground where their imagination could run wild. Percival’s memory proved to be the ember that, when fanned, gave rise to today’s WW&F Railway.

Percival’s lifelong interest in the WW&F led to a number of unique opportunities, each of which allowed a fragment of the broken WW&F to be put back into its rightful place. Through his employer, Central Maine Power, Percival learned that the railway’s right-of-way was being sold off by Winter Scientific Institutes. Percival approached them with an offer which they accepted, transferring the remaining WW&F right-of-way to him and, eventually, to the WW&F Railway Museum.

After acquiring the right-of-way, Percival applied to the state of Maine to establish a new company called the Wiscasset and Quebec Railroad Company (W&Q)—the name of the original railway which became the WW&F in 1901. The state refused the application on the grounds that the original W&Q had never been formally dissolved. They instructed Percival to hold a stockholders meeting and elect new officers to revive the dormant company. He did and the W&Q was back in business!

Despite the encouraging progress, there was a problem—the reborn railway had no equipment to run and no rail to lay upon their right-of-way. Percival had been working on this piece of the puzzle since the 1970’s. After the railway closed, a locomotive, boxcar, and flatcar along with some rail from the defunct Kennebec Central Railway was moved to Frank Ramsdell’s farm in Connecticut. After Frank’s death, his daughter Alice continued to maintain the equipment and the family farm. Percival reached out to Alice Ramsdell in an effort to help maintain the equipment and ensure its long term preservation. Today museum members joke that he spent most of his time at the Ramsdell Farm doing farm chores, but his tenacity helped gain Alice’s trust and return items from the original WW&F to Maine. First to arrive was the flatcar, followed by the boxcar, and later, Number 9 – the last extant locomotive from the original WW&F.

While working to return original WW&F equipment to the railway, the museum also acquired two internal combustion locomotives, including WW&F locomotive No. 52, a Plymouth diesel locomotive manufactured in 1961, that have proved invaluable in the museum’s efforts to rebuild the railway. The museum returned steam power to the railway in 1999 and has continued to restore and build new rolling stock. In addition, the museum has ensured that all existing WW&F locomotives and equipment have been preserved in a museum setting, and they have reconstructed or restored many buildings from the original railway.

What really sets the museum apart is the pervasive ethos that today’s railway is a continuation of the original railway, rather than a recreation or demonstration. Museum volunteers have adopted a work ethic and ideals similar to those of the original railways employees. No task is impossible or too large to be undertaken. Given time, ingenuity, and enthusiasm, anything is possible. They have taken up the work that was left in 1933 and continued it with contagious fervor.

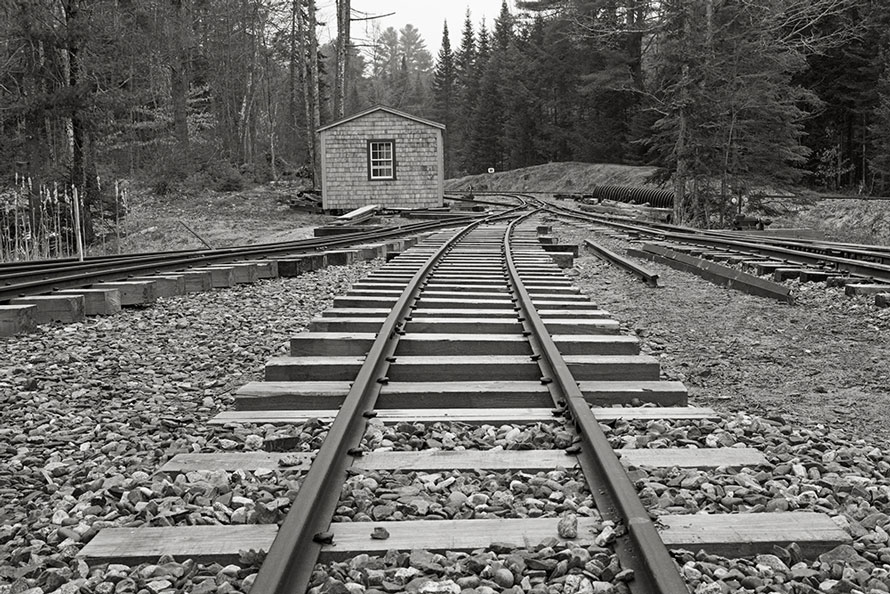

Visitors to the WW&F who are unfamiliar with the Railway’s history are often surprised to learn that nearly everything they see has been built or restored since 1989. Such is the authenticity of the WW&F. Although today’s railway is of new construction, the museum has been sensitive to preserving historic construction and maintenance techniques. With few exceptions, tasks are carried out today in a similar fashion to those that would have been employed over one hundred years ago. Members and volunteers have continued to bring together elements of the WW&F which were believed to be lost to time. Most importantly, they continue to share their enthusiasm for the WW&F, just as Harry Percival did, and they continue to invite individuals to participate in the railways rebirth.

. . . a sense of place almost as strong as the land itself.”

Just after dawn the railway is at its pinnacle. Narrow gauge rails unfurl towards the horizon. Early morning dampness is draped across the forests and right of way, hinting at the railway’s proximity to the shore, and its reason for being. (Originally the railway was meant to connect the interior of Maine and Quebec with an ice-free ocean port in Wiscasset) Ensconced in such sylvan environs, the woods and fields drown out the modern intrusions which have penetrated so much of the world we inhabit. Veiled in the early morning light the only interruption of the serene stillness comes from the sounds of nature: a wild turkeys strident gobble; the whistle of a red-tailed hawk; the crunch of leaves under hooves of nearby white-tailed deer. The placid sounds of nature are even more timeless than the railway itself, and thus the railway becomes the only intrusion – the singular mark humanity has left upon the land.

If we wait long enough we may hear the distant, throaty moan of the steam whistle, followed by the paced exhaust of the locomotive and the wail of steel wheel against steel rail. The golden glow of the locomotive’s headlight will punch through the horizon and make its way toward us until it is lapping at our toes, connecting us with the rest of humanity in a way that is ephemeral in its occurrence, yet lasting in our minds eye. Soon we will be alone again as the train slips over the distant horizon, and the rails return to their slumber.

The original railway, in its various forms served the Sheepscot Valley well. The rise and fall of the railway closely patterned the valley’s own success in agriculture and rural industry. Although the railway was gone for a time, it was not forgotten. What was preserved in the minds of some was returned to reality by others: it only ceased for a time awaiting the perfect moment to return to its place among the hills and dales. There, it has a sense of place almost as strong as the land itself.

(All photographs were taken on April 28, 2016)

Photographs Copyright 2017 by Matthew Malkiewicz – Lost Tracks of Time

Text Copyright 2017 by Stephen Piwowarski – WW&F Museum

What a great story of a surprising railway rebirth!

Wow! What a great story!

Great pictures that blend with the interesting story.

What a beautiful telling of a fine railway preservation. As a Narrow Gauge lover I thought I knew a fair amount about the railway and I still learned much. Thanks for sharing!

Great story and excellent images. Well done.

Great story along with some awesome shots!

This is so great, so much of the old railroads is lost forever. When I was a kid 8 or 10 yrs old, the the passenger trains used to stop in my town, to pick up people from the surronding towns. that’s all gone now. But it’s a great memorie, all the buildings are gone, and the the cattle pens for loading the cars.

I remember the little buildings that used to set beside the tracks, I remember most the sounds of the engines starting to pull away from the station, when they would lose traction and rev up and then back down to a chug chug chug and then break lose again rev up, it was so great, I lived 6 city blocks from the tracks and I listen to it ever night in my bed, it was beautiful.

I am a member and have a connection to the original in that both my father and grandfather were employees…..The volunteers that have recaptured the time and flavor of the original are awesome