Stations: An Imagined Journey

In the summer of 1992 I attended an industrial archaeology field school at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia and spent my free time investigating railroad action around Martinsburg, Winchester and the surrounding Shenandoah Valley. Two years later, my annual Christmas stocking-stuffer book was Michael Flanagan’s illustrated novel of railroad paintings, Stations: An Imagined Journey which to my surprise was set in the same geographic area. I was immediately drawn to the paintings, many of which looked like familiar places. The narrative seemed cryptic on the first reading. But I kept returning to the book, which eventually led me on my own journey, a personal exploration that rewarded me with a deeper understanding of my attraction to the railroad landscape.

Michael Flanagan was born in 1943 in Buffalo, New York and was raised in Baltimore, Maryland and the Shenandoah Valley. He started photographing trains at age thirteen, and in his 20s he briefly worked on a Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac (RF&P) track gang. Flanagan took art classes at Parsons School of Design and Yale University and supported himself as a book designer, with Jacqueline Onassis as a notable client. In the 1980s Flanagan’s renewed interest in the railroads of his youth influenced his artwork. In 1991, P·P·O·W Gallery in Soho gave Flanagan a one-man show of paintings of his imaginary “Buffalo & Shenandoah Railroad” called “Stations.” He wondered if the paintings could be made into a book and called on his client Jackie Onassis, who was an editor at Doubleday. She was captivated by the words Flanagan had added to the borders of his railroad images, and suggested he create a work of fiction instead of just a coffee table art book. Although Flanagan had never written fiction before, Jackie thought Stations, published by Pantheon Books in late 1994, could be “an American classic.”i

Flanagan documented all the nuances of the railroad landscape and saturated his paintings with them.

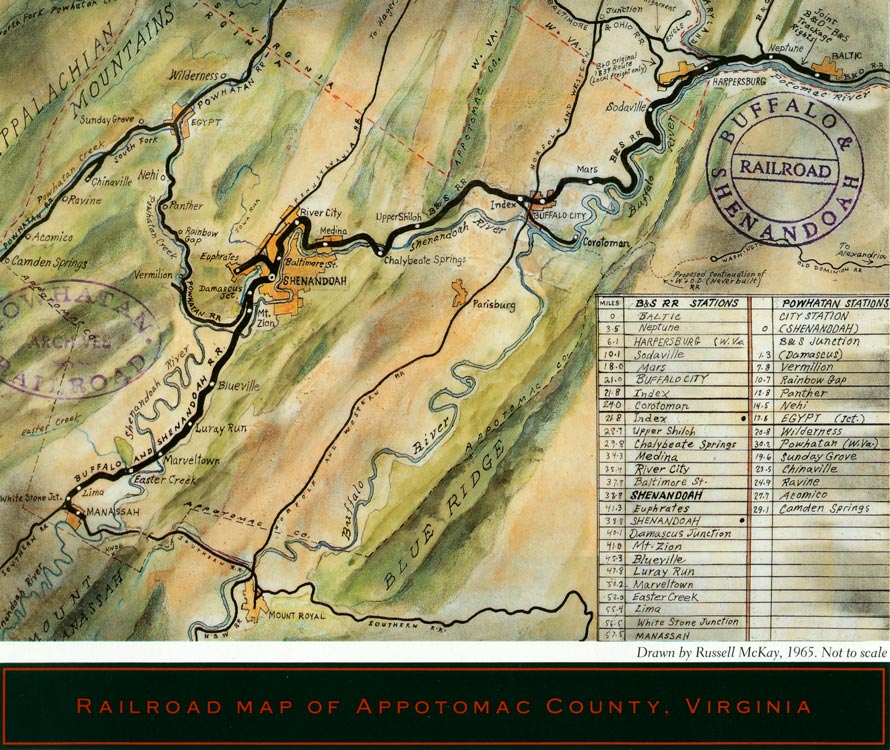

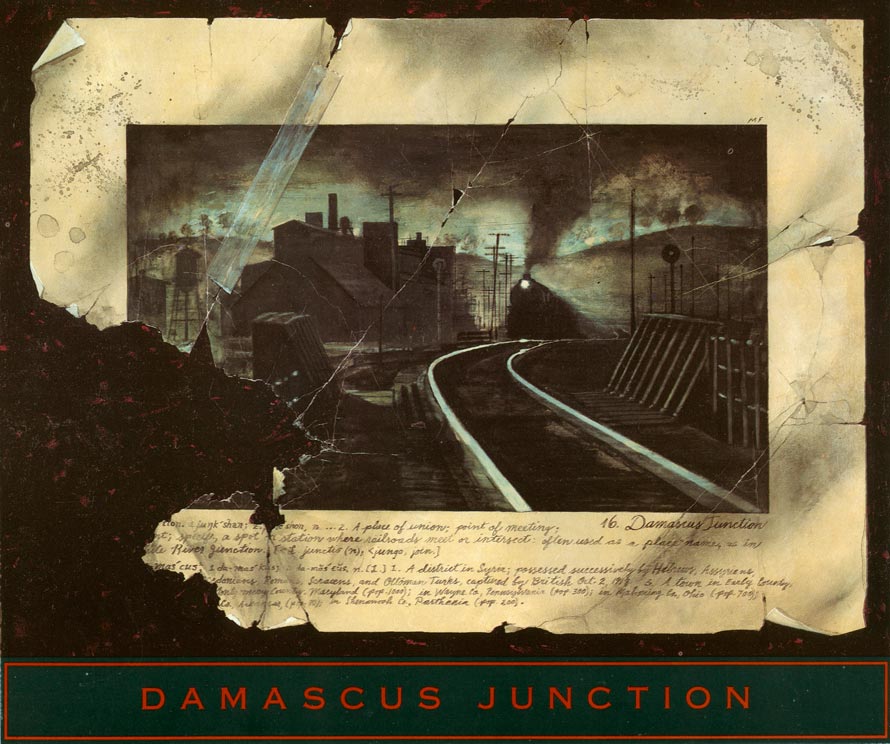

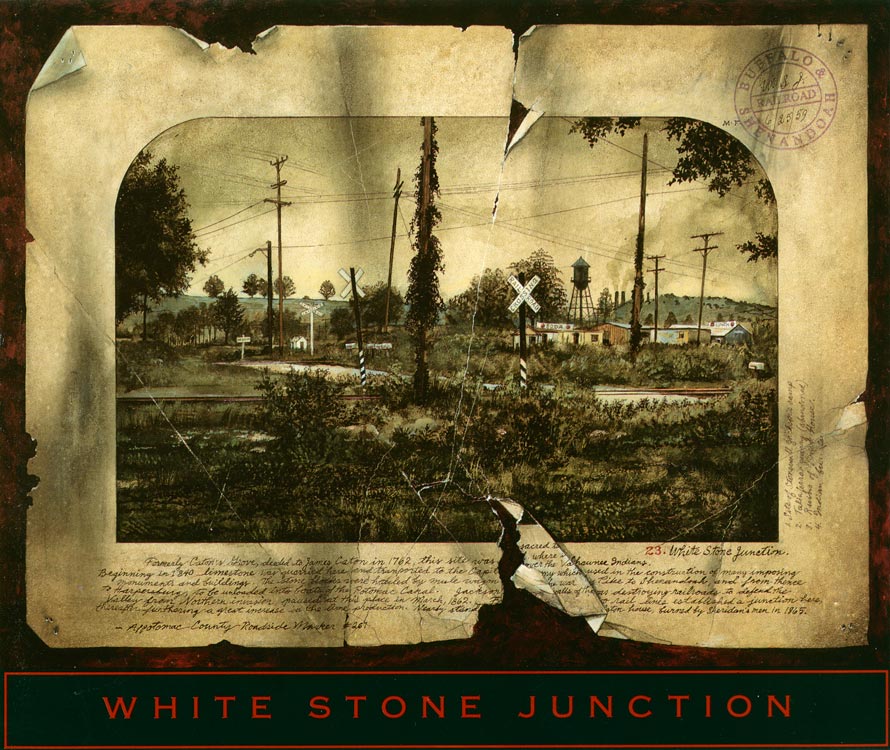

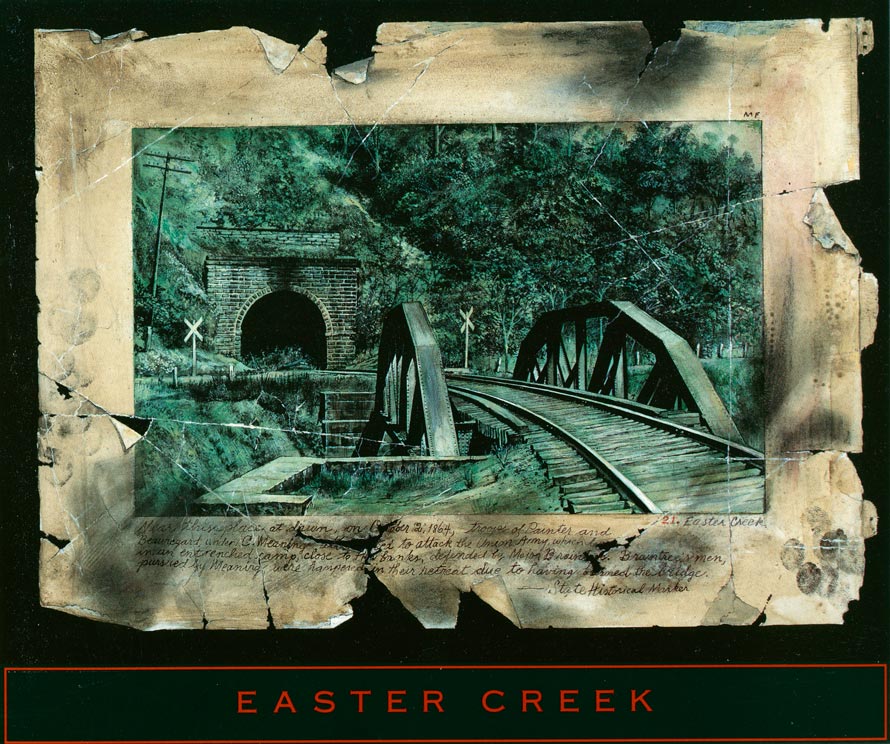

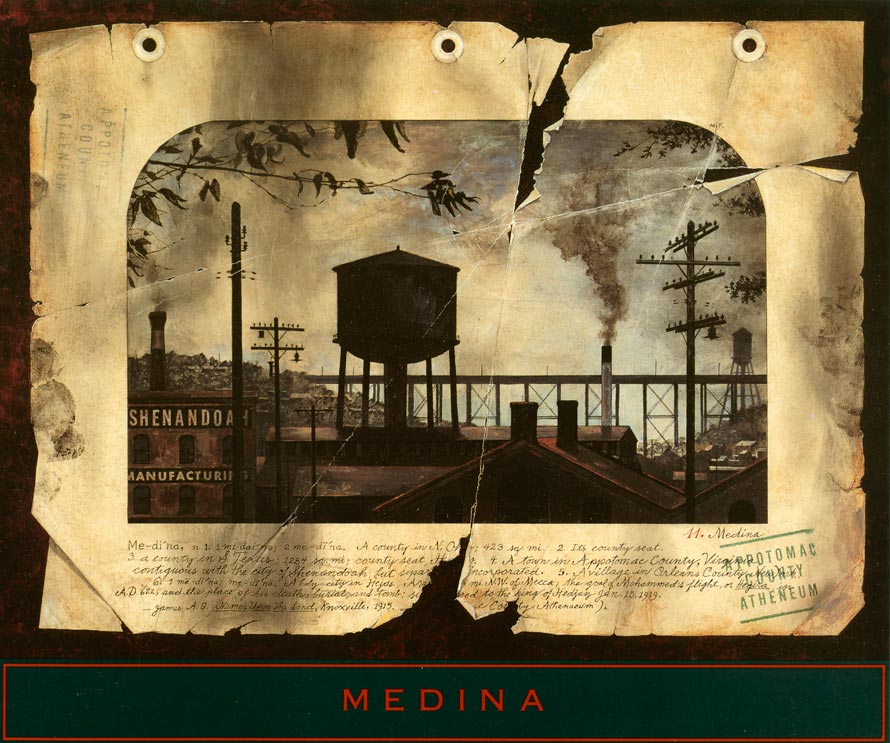

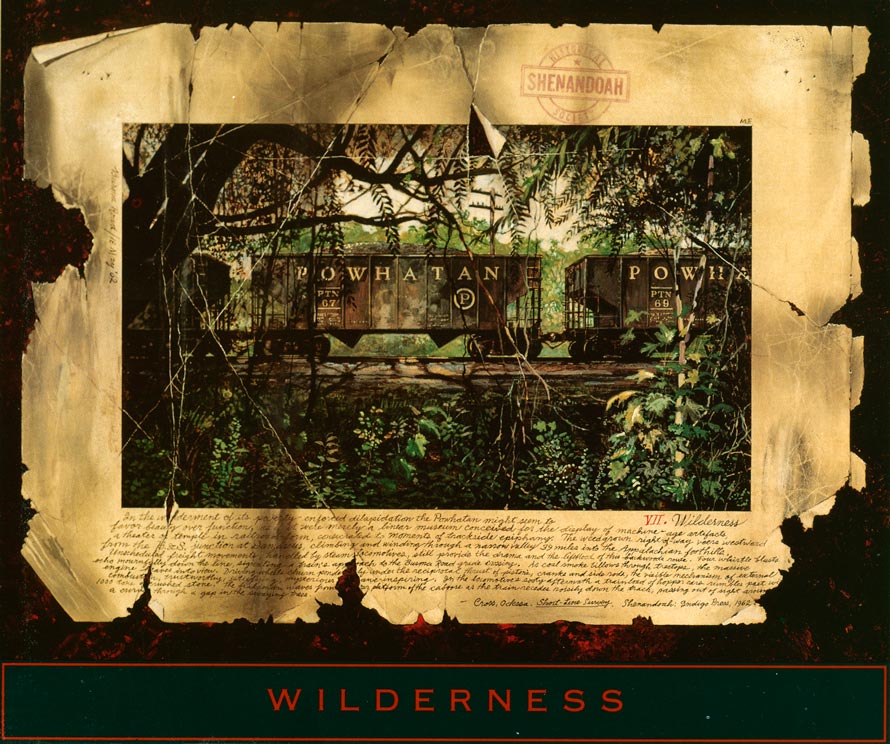

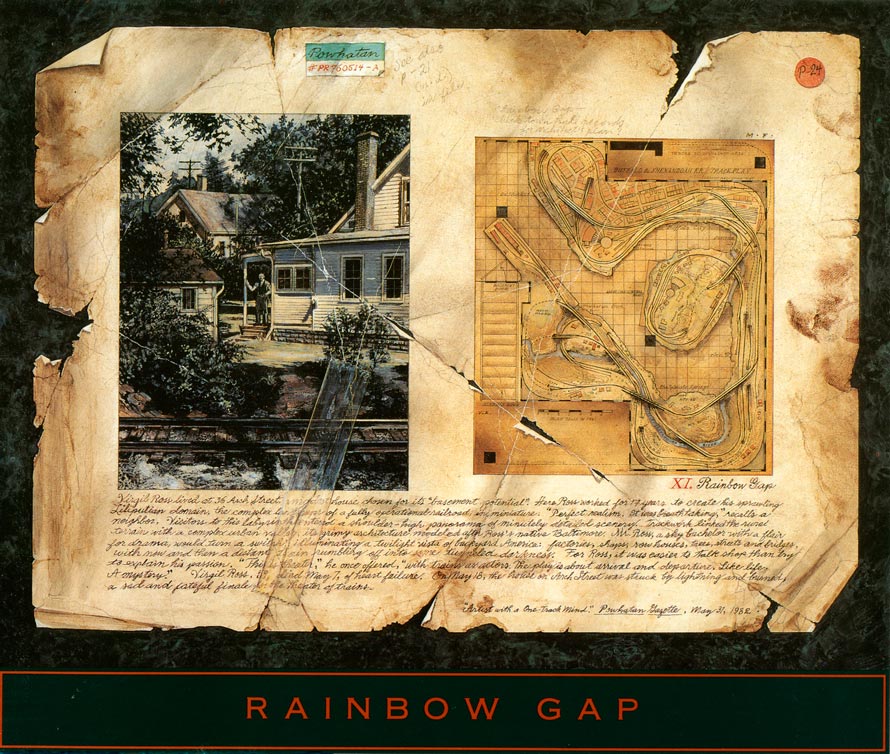

Stations: An Imagined Journey is complex, unconventional and perhaps unique in combining fiction, autobiography, painting, photography, and even model railroading to create not just a book, but an artifact. Harvard University landscape scholar John Stilgoe said, “no summary can adequately address the layers of character and narrative that embed Flanagan’s text and paintings.”ii As I began to research Flanagan’s life and work, it became clear to me that he was speaking about himself through the voices of his invented Stations characters. Flanagan’s narrator for his “imagined journey” is a retired newspaperman, Lucius Caton, who tells a fragmented story about his late cousin, Russell McKay, an itinerant photographer with a passion for documenting steam on shortline railroads in what he called a “genteel state of decay.” McKay had documented every named railroad place, or “station” on two shortlines in fictional Appotomac County, Virginia: the Buffalo & Shenandoah and the Powhatan. His project photo album is lost and is recovered by Caton, the pages damaged and hand annotated with explanations, history and musings. McKay’s photographs and the annotations form the content and structure of Flanagan’s Stations.

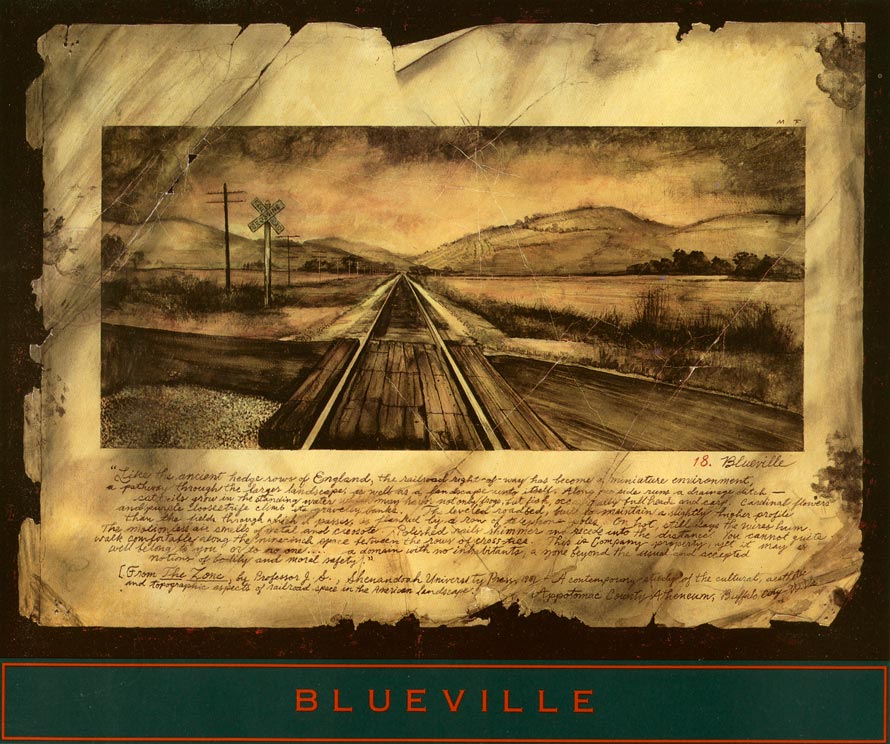

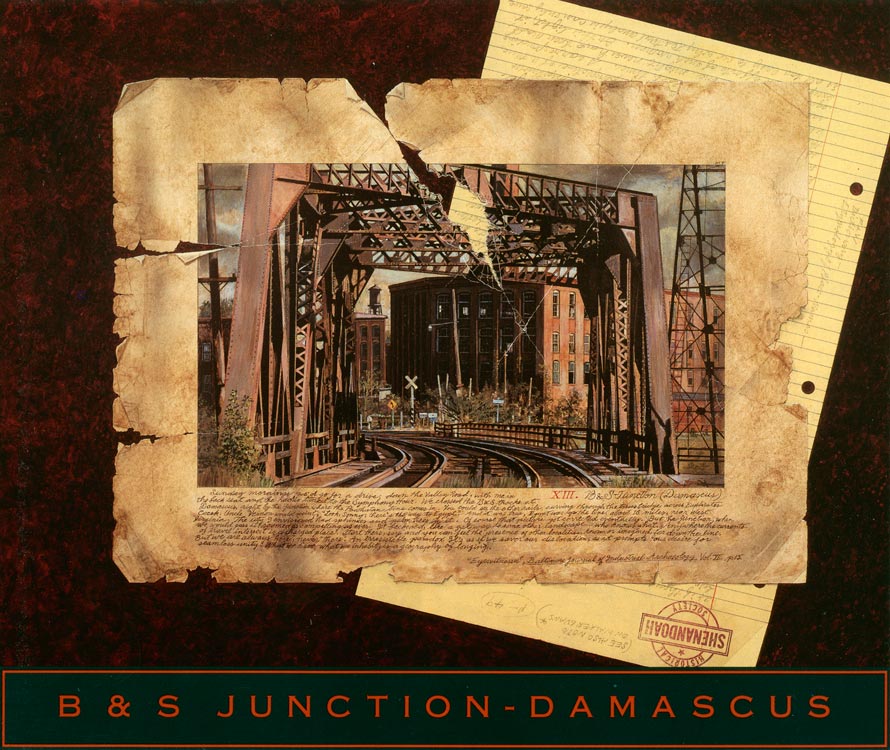

The paintings in Stations are based on photographs of real places taken by Flanagan or in some cases adapted from other sources, and then altered. The paintings look like black-and-white photographs mounted onto pages torn from a bound album, hand-colored and annotated in the margins. The paintings are done in a meticulous trompe l’oeil technique, appearing as distressed pages floating over marbleized backgrounds. My visits to Flanagan’s Connecticut studio were like visiting a little museum full of railroad atlases, maps and guides, books on Eastern United States Appalachian and Piedmont railroads, reference works on buildings and railroad equipment, and indexed boxes of reference photographs. Flanagan documented all the nuances of the railroad landscape and saturated his paintings with them. Through the cumulative weight of so many characteristic details, he succeeded in creating such a powerful “fictional authenticity” that his paintings make one feel they have somehow seen these places before. Indeed, according to Flanagan’s fictional narrator Lucius Caton, his cousin Russell McKay “was earnest about wanting to document and record these scenes, and getting the facts right.”

I’ve been interested or obsessed with trains and railroads ever since I was a child. Not so much with the hardware of railroads, but with the notion of railroads as routes.”

Like the paintings, the Stations text is also a complex combination of fiction and reality. The page opposite each painting includes sections of Lucius Caton’s narrative, Russell McKay quotes, and passages from an invented body of academic literature Flanagan created to contextualize his imaginary Appotomac County. These texts make sly reference to real-life American landscape scholars that some readers may recognize. They will also recognize references to O. Winston Link. Flanagan, speaking about Stations protagonist Russel McKay, revealed “it is Link’s voice and delivery, and my imagination.”iii Michael Flanagan knew O.W. Link well; they were in fact distantly related. Link may be the “voice” of Russell McKay, but a likely model for the character may have been photographer James P. Gallagher, who had the foresight to document fading steam railroads in the 1950s in the same Shenandoah Valley territory as Flanagan’s Russell McKay.

Of the thirty-eight Stations paintings, only ten show trains, and seven of those just locomotives, all steam. However, the paintings contain a multitude of bridges, grade crossings, tunnels, crossings, telephone poles, and above all, water towers. Michael Flanagan said, “I’ve been interested or obsessed with trains and railroads ever since I was a child. Not so much with the hardware of railroads, but with the notion of railroads as routes. I like trains, but it’s the track that comes first.”iv

More poetic, she said, to leave out the trains.”

For many Stations readers, the paintings are more accessible than the text. That was the case for me at first, but once I understood the autobiographical content in Flanagan’s narrative, it was clear that he needed another, different medium to express his feelings in a way no less important than the paintings. Many of the motivations and stories Flanagan attributed to his Caton and McKay characters were based on his own life. Flanagan said, “the text became as important to me as the pictures. It helped unlock this world, bring it to life. I want my paintings to be like detective stories. There are clues planted in the text and in the pictures that should inspire the viewer to hunt, to find the sources, to discover that this fictional place does have a real life correspondence, to compare how it departs from reality or how it is close to reality.”v

Model railroading, another art form that combines fantasy and reality, was important to Michael Flanagan and the construction of the Stations paintings. Flanagan always wanted to build a model railroad and originally conceived his Buffalo & Shenandoah as an HO-scale layout before he began the paintings, but building the B&S in three dimensions was limited by physical constraints. Once the two-dimensional paintings emerged, space was no longer limited, and Flanagan was free to expand his imaginary world and invent the adjoining Powhatan railroad and its series of paintings. Flanagan’s approach to featuring and altering real structures to create authenticity in his paintings is similar to the process scale modelers call “prototyping.” Flanagan’s paintings are not literal copies of photographs, they are “scratch-built,” to use another modeling term, with added elements from a library of visual reference material and personal experiences. They are certainly “weathered.” Later in life Flanagan finally built his own HO-scale layout and got to know several accomplished model railroaders. Like Stations, his layout was an imaginary world and a personal reflection modeled on a pastiche of northern Shenandoah Valley towns.

A railroad is a conduit, it links you to places you can’t see. For me that’s the ultimate: to stand by the tracks, waiting for a message from afar.”

Michael Flanagan was forthcoming about the meaning of his work. For him, Stations was about the evocative power of railroad tracks, human obsession, and coping with loss. For Flanagan, the power in railroads was not really in the trains, but in the places where they had been, or could be. Encountering or lingering in this “outlaw landscape” as he called it, created an automatic anticipation and heightened awareness. Flanagan said, “a railroad is a conduit, it links you to places you can’t see. For me that’s the ultimate: to stand by the tracks, waiting for a message from afar.”vi Stations is also about human obsession with the past, with machinery, with arcane special interests. Flanagan said, “the book isn’t really about trains. What I’m interested in is the subject of obsession, whatever it would be. Something bites you at an early age, gets under your skin, and you can’t get rid of it.”vii As Lucius Caton observed of Russel McKay, “passion breeds its own subculture…its own literature and terminology, a whole vocabulary of shared mania.” Finally, Stations is about dealing with loss. According to those who knew him, Flanagan mourned his whole life for the lost era of his childhood, not just steam trains, but all the vernacular details of the world they ran in. Flanagan’s Lucius Caton said about looking down railroad tracks, “it beckoned like a gateway to some other landscape… But we are always “here,” never “there,” what we have, what we inhabit, is a geography of longing.” And Flanagan’s Russell McKay said, “some of us express longing through art.”

Flanagan said, “my paintings are about travel, about the unconscious, the imagination and our ultimate paths in life. I’m interested in the past as it constantly asserts itself in my own memory, my own childhood. It hammers at me, it pulls at me, it’s very alive for me. Not in the sense of a weepy nostalgic yearning for the good old days, but in the sense of some unfathomable mystery.”viii Flanagan wrote in his Stations project notebook, “it is a common impulse to honor the deep mysteries of time and place through acceptable pursuits like archaeology, and the classification of minutiae, which only mask a deeper, unacknowledged, irrational fascination. Only the mystery counts. Not the “stuff,” but what kind of feelings the stuff evokes.”ix Stations was Flanagan’s way of externalizing, exploring and addressing his feelings of loss and obsession with “the tracks” by evoking that landscape in a fantastic way. From reality and imagination, he built a two-dimensional fictional world, with its own imaginary creative and intellectual “support group” of people who cared enough to photograph it, write about it, reflect on it, and honor it.

“I came to bid farewell to a piece of history, a familiar landscape, a whole way of life.”

Although Stations is just one artist’s attempt to address and express his feelings about the railroad landscape, it has potential to help all of us who are drawn to that environment understand and explore our feelings about it.

Michael Flanagan died in Connecticut in August, 2012 after an 8-year battle with colon cancer. A quote from one of Flanagan’s fictional Stations characters serves as a fitting epitaph: Oscar Caton, a local historian interviewed about the last passenger train on the Powhatan railroad, said: “I came to bid farewell to a piece of history, a familiar landscape, a whole way of life.”

Stations remains a hidden classic of railroad art and literature that deserves a spot on the shelf of any thoughtful railfan.

Notes All artwork and quotes unless otherwise cited or credited are excerpted from Stations by Michael Flanagan: Original artwork and text from STATIONS by Michael Flanagan. Copyright © 1994 by Michael Flanagan. First published by Pantheon Books. Permission arranged with the estate of the Michael Flanagan. All rights reserved. This essay is based on author Matt Kierstead’s longer article, “Michael Flanagan’s Stations: An Imagined Journey: An Artist’s Multi-Layered Exploration of the Railroad Landscape” which appeared on pages 32-47 of the Center for Railroad Photography & Art’s Winter 2015 issue of their quarterly publication, Railroad Heritage. Interested readers will find more information on Michael Flanagan’s Stations paintings, text and meanings in that essay. Stations is long out of print, however used copies are readily available from the usual Internet sources. Matt Kierstead welcomes comments or questions about Stations at: matthew.a.kierstead@gmail.com.

i "Famous," unpublished 1999 Michael Flanagan essay, estate of Michael Flanagan. ii Stilgoe, John. "Michael Flanagan's Stations." American Art, Vol.11, No.2, Summer 1997, p.45. iii Michael Flanagan as quoted by Jerry Tallmer in "Michael Flanagan," New York Post Weekend, "Eye on Art," March 8, 1991, p. 47. iv Michael Flanagan as quoted by Trinkett Clark in "Parameters," a catalog printed in conjunction with a one-man show of Michael Flanagan's railroad paintings at the Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia, October 18, 1992-January 3, 1993. v Michael Flanagan as quoted by Trinkett Clark in "Parameters." vi Michael Flanagan as quoted in "The Imaginary Railroad," The New York Times Magazine, Sept. 25, 1994, p. 50. vii Michael Flanagan as quoted by Jerry Tallmer in "Remembrance of Trains Passed," The Observatory, December 26, 1994-January 2, 1995, p. 19. viii Michael Flanagan as quoted by Trinkett Clark in "Parameters." ix Michael Flanagan’s Stations project notebook, estate of Michael Flanagan.

Matthew Kierstead – Copyright 2017

When Stations first came out, my stepmother bought a copy for my father; I read it, and I didn’t get it at all. Fast-forward twenty years, and Matt Kierstead’s deep explanation of the book and everything it embodies changed the way I looked at the book completely, and it also made clearer the reasons I have chased trains and photographed them for almost my entire life: not about the stuff, but about the feelings the stuff evokes. Stations indeed deserves the adjective “classic”, and it does indeed deserve a spot on every thoughtful railfan’s shelf.

I met Matt through Oren; the three of us have done some train chasing and exploring in the anthracite region of Pennsylvania. I was fortunate enough to be attendance for Matt’s presentation of “Stations” at the Conversations Northeast 2016 by the Center for Railroad Photography and Art. Similar to Oren, I was given a copy of the book by Matt prior, but was not overly impressed. After Matt’s passionate and well researched talk, the book now ranks high in my collection. “Stations” and this essay is a perfect match for this website – about the environment and landscape the train resides in more than the machine itself.

I too was given a copy of the book as a gift and loved the style and content of each of the paintings. Each has a romantic vision of the railroad and supporting infrastructure that appealed to me. I have looked at the book many times, but never read more than a few pages of the text as I couldn’t grasp the story. Matt’s presentation at the Northeast Conversations completely changed my understanding of the book and I went back and read it cover to cover. The story is a bit overly complex, but I was now determined to uncover its layers with the insight that Matt provided. I get it now, but I think part of it is that I also matured and can relate to the book’s emotional perspective of the railroad and not just as a bunch of cool pretty pictures. Like Oren wrote, I now see trains as more than just “stuff”, but for the emotions and connotations they carry. It took 20 years of growing and Matt’s presentation for me to see the gift of this book.

As an engineer who ran trains on branch lines as well as along main lines that went through industrial areas these few pictures look very familiar even though it is little parts of them that do so! Excellent story