Part Two

Piedmont Subdivision

Trevillian, Pendleton, Buckner, Doswell, Hanover, and Ellerson

Trevillian was a larger wooden depot with the town post office inside the former waiting rooms. I am uncertain what may have been stored in the freight room. Local lore was that the station building was used as a hospital during the civil war, but I am uncertain whether it was the one shown above or an earlier structure.

Pendleton was a closed agency with doors wide open. My understanding is that the agent at Mineral had spent a few hours there daily until the North Anna Power Station at Frederick Hall increased traffic, so that Pendleton became a non-agency station. I retrieved a tariff case from the depot which now resides at Boyce.

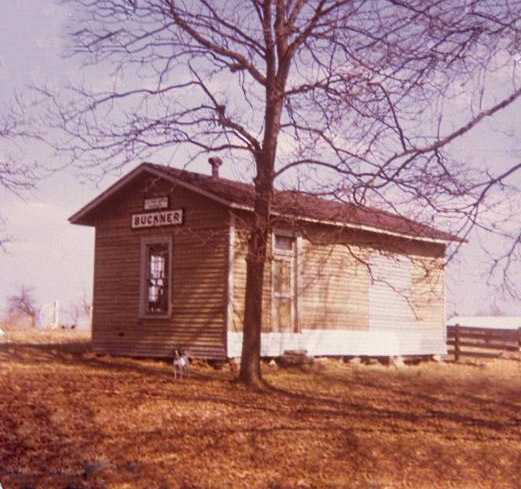

Buckner depot was moved away from the C&O track and onto nearby farmland. My expectation is that none of the original content survived.

The brick station at Doswell and HN Tower appeared then as they do now, except that the tower windows are now boarded up. Going up the steps part of the way, one could see into the tower operator’s bay window. I was certain that I could see the outline of a telegraph sounder resonator box and wrote to the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac (RF&P) Manager of Mail and Express, who was also responsible for towers and agencies. The response was that there weren’t any telegraph items inside the town. I suppose that Charlie Johnson was correct because during a later visit, no such items were within view.

During earlier years, a C&O train order signal was positioned to the right of the tower. I believe the C&O contributed 33 percent of the operator’s wages while the RF&P covered tower maintenance and the remaining cost of operators. Certainly, the majority of movements through this interlocking were RF&P freight and passenger trains. The telegraph call “HN” was derived from the original name, “Hanover Junction.”

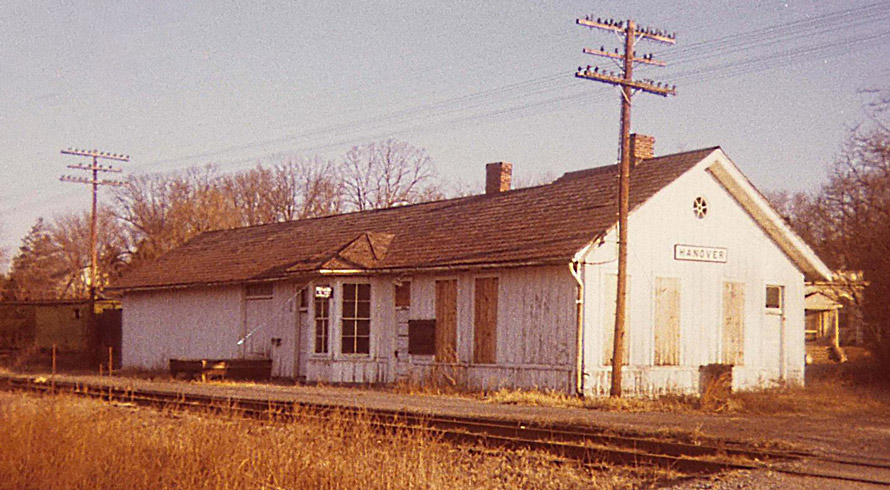

Hiking along the C&O in 1969, I encountered the retired Hanover depot. It had apparently lost its agent not too long before my visit. It was also along a former alignment in sight of the main track without any other buildings in close proximity.

One of the bay windows was unlocked which I slid open to slide inside. The desk telephone still worked and there was little inside other than a shelf in the freight room which had about a dozen 1950s Official Guides. Apparently, some years before someone wanted to find out how far a bullet would penetrate the issues, so they were lined up and shot at once. The bullet made it through almost five issues. I retrieved them all and carried the most damaged one my car to look up rail lines during travels.

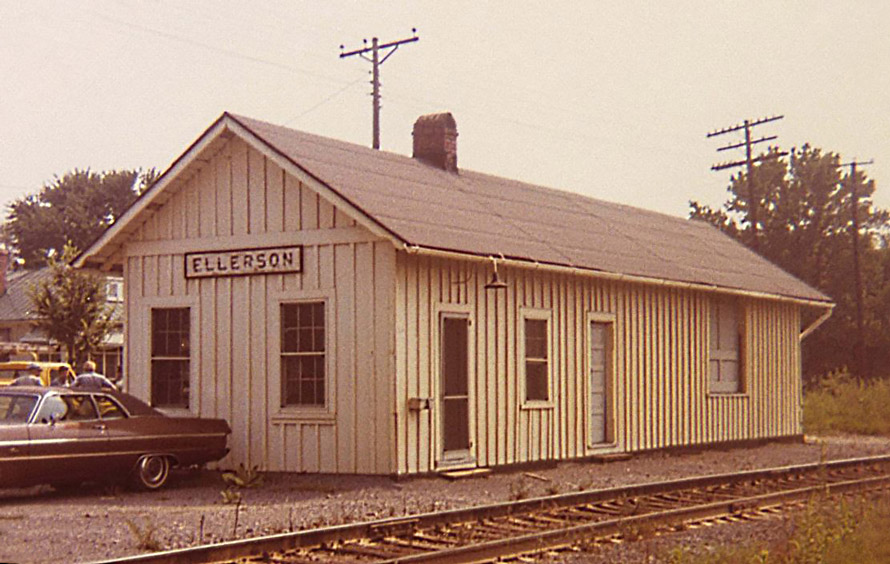

My first glimpse of Ellerson was as I rode a C&O train to Richmond to meet the Chief Dispatcher, Jim Pickett. It was a white depot and I think the agent’s name was Herbert Wiseman. It was not an agency that I ever had an opportunity to work and believe it covered car loadings of sand at Sandco.

Gordonsville, Virginia

There were two separate functions at Gordonsville: the depot agency and the interlocking tower. Kenny Williams was the daylight operator at G Cabin. His brother Herbert Williams was agent, a position that I never worked. At one time, there was also a clerk, but I believe passenger and freight traffic had declined by 1971 so that there was only a daytime agent. Freight traffic at Gordonsville was pulpwood loading onto wood-rack cars, plus an occasional propane tank car delivered to a retailer a mile east of Gordonsville.

G Cabin was my “home terminal, meaning that when I worked at that location, no per diem was paid. All of my mileage to other locations on the Piedmont and Peninsula Subdivisions were calculated by track miles. Road miles were used for locations on the Rivanna Subdivision.

The tower had a Union Switch and Signal Centralized Traffic Control machine which controlled passing tracks at Massie, Campbell, Lindsay, and Gordonsville. Most of these passing sidings were short and seldom used. The track configuration at Lindsay was configured for the era when steam coal would be set out at Strathmore from eastbound trains on the Rivanna Subdivision. A mallet (called a “Bull Dog”) would haul the coal from Strathmore to Lindsay, pulling up on a track adjacent to the main line, leaving the loads, then picking up any set-out empties for a return trip to Strathmore via the Virginia Air Line (VAL) Subdivision. The loaded or empty hopper cars were transported between Lindsay and Potomac Yards via freight trains 890, 891, 892, 893, 894, and 895.

As a sidebar note: I had been told that there were three passenger trains each way across the original C&O main lines, each departing their initial terminals approximately eight hours apart. There were connections between Newport News and Charlottesville as well as between Ashland and Louisville. A similar approach was used for freight trains; they had scheduled departures from their initial terminals with similar connections. For example, train 95 operated westbound from Newport News to Clifton Forge via Gladstone. Train 795 operated between Richmond and Clifton Forge via Charlottesville. Train 895 departed Potomac Yard for Charlottesville via Gordonsville. This summary may not be entirely accurate, but that’s my understanding of oral history.

By 1971, activities at G Cabin were substantially diminished. There were at one time three manifest trains each way daily between Charlottesville Yard and Potomac Yard, a local freight covering that line to Orange as well as between Gordonsville and Fulton, plus three passenger trains each way between Charlottesville and Washington along with Charlottesville and Richmond Main Street Station. When I began posting, Amtrak trains were limited to one each way between Washington, Newport News, and Charlottesville. Likewise, there were a pair of freight trains between Charlottesville Yard and Potomac Yard, plus a westbound manifest freight and a local freight eastbound between Charlottesville Yard and Fulton Yard. Consequently, there were long lulls during each trick. I recall that between 1:00 and 5:00 a.m. the model board was dark.

Prior to around 1969, G Cabin was a teletype office. When there were car pick-ups and set-outs at Lindsay, the train consist tape from either Potomac Yard or Charlottesville Yard was received, then the punched tape for the cars added/dropped were transmitted to the destination terminal at the end of the original tape. Strathmore created the wheel report as a teletype message for loads heading northbound. G Cabin created the teletype report back to Strathmore for empty hoppers.

All trains heading eastbound toward Richmond at G Cabin received a clearance card because the territory past the interlocking limits was automatic block territory from there to Sandco. All trains ran as extras, therefore, a train order was also required, which usually read much like this:

Order ## C&E Extra #### East Engine #### run extra Gordonsville to Sandco. Gordonsville [time] all superior regular trains have arrived or left. J.L.P.

No trains operated over the VAL during any of my G Cabin tricks, which also would have required a clearance card. I’m uncertain how that would have been accomplished, since Lindsay was seven miles from G Cabin, unless the Bull Dog engines during the steam era ran to Gordonsville for water and to be turned on the wye for a return trip to Strathmore. The local freight from Charlottesville Yard for the Piedmont Subdivision was the only regular clearance card recipient that I recall. It usually departed Charlottesville Yard around 5:00 p.m. with no work prior to Gordonsville. The agents at Louisa, Mineral, and Beaverdam would call G Cabin on the block line and dictate a message to the conductor that stated how many loads or empties were to be picked up and where the waybills were located. There were no bill boxes on these three stations, so the waybills and switch-list (if there was one) was left in the telephone box closest to each depot.

There are several vivid recollections about the other operators:

Kenny Williams – He wore a suit and tie every day to the tower. After arrival he hung the jacket and took off the tie, then settled into the operator’s chair. My perception was that since Gordonsville was a rural community with few white-collar workers, he wanted to distinguish himself as a professional while in public. Soft-spoken, he was still a proficient telegrapher. Blair Thompson brought a key and sounder to the town once. Kenny connected the phone line to the Southern Operator at Orange, said nothing, and sent the office call “OH … OH … OH…”

The operator replied, “Who’s calling OH?”

Buddy Mahanes – As the swing operator, he kindly shared a lunch sandwich with me while I was posting. Buddy was a Justice of the Peace and occasionally scheduled a marriage after he was off duty. During quiet periods at the tower, he prepared grievances since he was a Local Chairman, Brotherhood of Railway, Airline, and Steamship Clerks (BRAC) which represented agents, operators, and clerks on the Piedmont Subdivision. Since he was a member of the Gordonsville Volunteer Fire Department and G Cabin was the only 24-hours daily, 7-days weekly activity in town, he arranged with the C&O to allow the emergency phone number at the tower, Temple 2-2222. Instructions were to answer the phone when it rang, record the name, address, phone number, and emergency type. Next, there was a magneto box on the wall that was cranked which initiated the fire alarm. When a volunteer responded, they called the emergency phone to request the address information.

King Joseph Tardiff – He was the last of the boomer operators. He had previously worked for the Southern Railway Washington Division until so many stations were eliminated that there was no work for extra operators. During a previous year while photographing Southern depots, I found a clearance card at North Garden station which was vacant and open to the wind. King had an appearance similar to Buddy Hackett, with similar humor. He was working third trick one morning when I had arrived around 7:30 a.m. to relieve him. During the turnover—which never took long and was more small-talk than train line-ups—the emergency phone rang. King answered “Fire Emergency,” listened, eyes widened, the he said “You have a wrong number, this is TE-2-2222.” After he hung up, he confided:

“That was a lady; she said ‘You can come over now; the old man is gone.’”

Lewis M. Patterson – Lewis usually worked second trick. He owned a back-hoe and during daytimes was a contractor for digging holes or ditches. There was plenty of evening time for him to prepare invoices and record payments.

Percy Heath – He lived in Gladstone and commuted to G Cabin for the midnight to 8 AM shift. Affable and as I previously mentioned, he worked a slow shift. I’m uncertain how he stayed awake.

During July 1971, Assistant Trainmaster Frank Schumaker arranged for a rules refresher class for agent-operators in the Gordonsville depot waiting room. My perception is that there hadn’t been one for several years. The notable aspect was that Hunter Miller and Lewis Patterson had never met each other face to face. People arrived gradually and were mostly quiet, but when Hunter spoke to Steve Thruston, Lewis recognized his voice. For that moment, it seemed like a family reunion of long-lost relatives.

1972 was an eventful summer. I finished my Bachelor’s degree at the University of Virginia during early June. Rather than walking in the procession through the Rotunda and down the Lawn, then sitting for two hours in the June sun in front of Old Cabell Hall, I watched a few friends in caps and gowns pass, then ducked into New Cabell Hall and picked up my degree. By 4:00 p.m. I was seated in the operator’s chair a G Cabin. I definitely made the better choice of how to spend my afternoon and evening.

A few weeks afterwards, I had finished the daylight shift at G Cabin. A storm was approaching and I drove to my Charlottesville apartmen—now gone and replaced by high-rise apartment buildings. As soon as I arrived at my apartment shortly after 5:00 p.m. the phone was ringing as I entered. The Chief Dispatcher’s Office asked if I could get back to G Cabin for the midnight trick because Percy Heath, the regular operator, was stranded by rising water near Bremo Bluff. By the time I got back on the road, the route between Shadwell and Gordonsville was impassable. I drove through a downpour that was like Niagara Falls on the windshield, riding up US Highway 29 with the North and South Branches of the Rivanna River close under the highway bridges. I made it to Ruckersville, then rode east on US Highway 33 to Gordonsville. I sat along with Lewis Patterson as the storm began to ease, then took over at midnight although no trains were moving.

During the ensuing morning, Ellis O. “Eli” Fortney, track supervisor, high-railed from Gordonsville to Louisa. There was one wash-out along the line that was repaired with dumped ballast. I don’t recall other roadway damage between Charlottesville, Orange, and Richmond. It was a different story along the James River; the small trailer placed at Bremo to replace the damaged wooden station during Hurricane Camille in 1969 was swept away.

Louisa, Virginia

During the summer of 1971, Louisa was the only passenger train stop between Trevillians and Sandco on the Piedmont Subdivision. I did not have an assignment there until 1972; by then, the passenger stop had been discontinued. It was the only station which had a clerk. That position disappeared by 1973 since there was no passenger service and shipments of agricultural implements and other freight declined.

For many years, V. E. Kiblinger had been agent, but he retired a year or so before I began working. Hunter Miller, who had been working at Beaverdam, bid on the assignment. The attractive benefits of that agency was the assistance of Dorothy McDonald, clerk, as well as the Railway Express Agency commission. A custom wood-working and furniture shop made frequent shipments of high value express shipments. I handled the billing of one during a 1972 week, but of course Hunter collected the commission when he prepared the monthly statement.

The clerk handled all of the preparation of bills of lading, submitting daily reports to the Zone Accounting Bureau at Richmond, and demurrage records. There weren’t many tariffs kept at agencies while I was working but when supplements were received, the clerk was responsible for filing these. The agent was responsible for the blind siding reports and preparing messages for local freight work. When there were passenger trains, ticket sales, maintaining on-hand cash reports, accounting for ticket stock, and making bank remittances were also part of the Lousia agent’s workday. As the operator, the usual duties included preparing clearance cards and train orders, ordering and releasing cars, and OS’ing trains on the daily train movement report.

After Hunter retired, Drema Coleman was the agent without a clerk. The Louisa agency closed around 1980, after which I purchased the Victor safe. After passenger trains were discontinued, there were still cash remittances for Railway Express collect or prepaid shipments. Hunter taught me to count the money in the safe at the beginning and ending of a shift, even if there were no transactions during the day. By 1973, all that was kept in the safe were pencils.

The purchase of the Victor safe during 1980 was arranged through the B&O Museum at Baltimore, Maryland. At that time the B&O Museum handled railroad artifacts through a catalog, but if someone wanted to purchase a specific item, the B&O Museum contacted the division office to discuss availability. For $500 as-is, where-is, the safe was mine. I hired a safe moving company to relocate the safe from the depot to my Alexandria home. Chris Topalu, Manager – Station Operations met us and unlocked Louisa. The safe was the only remaining item that I recall inside the depot; the train order levers frame had been smashed rather than unbolted from the floor for removal as scrap metal.

Mineral, Virginia

As I mentioned in Part One, Steve Thruston taught me the principles of agency work. If I had a question during the first summer I was working on the C&O, he was the first person I checked with via the block line phone. Steve began working around 1947 at Providence Forge, but had settled in Mineral and lived in a house a few blocks away. I think that when he retired around 1980, “he took his job with him” and the agency closed.

During the construction period of nuclear units 1 and 2 at the North Anna Power Station, Mineral’s agency could have justified a clerk but never received one. During 1971, there were almost daily deliveries of between ten and twenty carloads of piping strapped to flat cars or in gondolas. The construction materiel was consigned to Brown and Root or Bechtel. My speculation is that the revenue for carload deliveries to Frederick Hall under the Mineral agency probably exceeded the total for all other Piedmont Subdivision agencies combined.

Within the Mineral town limits, there was an occasional load of pulpwood shipped to West Point or Covington, Virginia paper mills. It was otherwise a sleepy community; a far cry from 1920s mining activities that gave the town its name.

A notable feature in the agent’s office was the patch board. All communication wires along the Piedmont Subdivision bridged through that panel, many of which were not accessible at any other station. In the event of a line problem, the wire chief would contact the Mineral agent-operator to insert cords to patch around the failure. A story about Howard “Buddy” Mahanes during the 1950s was that he was a student operator at the station. There was a clothing factory nearby and many of the women workers would take their bag lunch and sit on the station’s loading dock in the early afternoon shade. Buddy, with operator’s bay windows open, would impress the passers-by as he practiced typing to copy Associated Press news reports from the AP wire. It was said that operators in earlier years became sports announcers to town residents congregating at the depot by giving play-by-play reports of sports events on the news wires.

Like most C&O stations, Mineral was of wooden board-and-batten construction. It was air-conditioned in the winter and heated in the summer. In that rural community it was often chilly despite being a June, July, or August morning. More than once while working there, I lit the coal “Warm Morning” stove in the agent’s office. If there had been a means for averaging the daybreak chill with the setting sun heat, the agent’s office would have been comfortable all day.

Steve decorated the office with calendars featuring cutesy kittens. The waiting rooms were barren and unused. Occasional visitors were shown the Tucker Alarm Tills under the ticket window ledge. The agent could open the cash drawer by pulling a particular combination of four tabs under the drawer. If the correct tabs were not pulled, the drawer made a bell-ding sound. That was early 20th Century security technology at its best.

Beaverdam, Virginia

There was a wide gap in agencies between Mineral and Beaverdam, mostly because there was no local industry and small communities. Were it not for an aplite mine at Beaverdam, there likely would not have been an open depot at that location. Aplite is a form of silica used for glass making. The only other aplite mine along the Richmond Division that I am aware of was at Dillwyn at the end of the Buckingham Branch. In both cases, the commodity is high-revenue. A small covered hopper car dedicated to that service had a 100-ton capacity. During a usual weekday, about five cars were loaded at Beaverdam.

The brick depot had the distinction of being among the oldest buildings anywhere. Local lore was that it was burned by both Confederate and Union forces as the area north of Richmond was occupied by one side or the other. Possibly because of events 120 or so years earlier, the brick wall had deteriorated. Inside the freight room, there was pre-1900 graffiti and later cans and bottles tossed from the freight room onto the ceiling over the agent’s office. At one time, the village post office was located in the east end of the freight room. It was relocated to a new stand-alone brick building during the 1950s.

The Piedmont dispatcher was blind in the automatic block signal territory, relying upon train passing times reported by open agencies. Beaverdam had an eastbound signal visible from the operator’s bay window that was ahead of the manual switch for the spur into the aplite mine tipple and a switch to the house track behind the depot. These automatic block signals were lit on approach from either direction, so the operator at Beaverdam knew of an approaching train within an OS report from the previous station via the block line. Mineral alerted Beaverdam about eastbound trains, but there was no open station between Sandco and Beaverdam for a westbound train passing report. On occasion, the dispatcher would ask the operator if the signal was actuated to judge the progress of a train on the Piedmont Subdivision.

I enjoyed working at Beaverdam, in part because I had good memories of my first paid week on the C&O. At 4:00 p.m. I pulled down the shades, locked the doors, and relaxed until the following weekday morning at 8 a.m. On occasion, I would make the next day easier by typing several straight bills of lading (BOLs) for outbound carloads, so that all that was required to finish the BOLs was to add the car initial, number and weight.

The first week at Beaverdam was memorable for its beginning. As I mentioned, I did not have a place to stay during the 1971 summer since I had the expectation that I would be working at G Cabin. I had sub-leased the Charlottesville apartment I would occupy during my fourth year at the University of Virginia. The boarding house basement bed at Gordonsville was rented week-to-week, so I moved to Charlottesville. I received a Sunday afternoon telephone call from the Chief Dispatcher’s office assigning me to Beaverdam for the following Monday through Friday. I hadn’t expected that, but checked with Blair Thompson and he referred me to a fellow in town from Ashland that was visiting other friends. He agreed to drop me off on his way home and would leave at 9:00 p.m.

We traveled along Interstate 64 and naïve me, I expected to see the town name on an Interstate exit sign. Neither of us had a map and I had no idea where Beaverdam was via highways. Although he originally promised to take me to the depot, he reneged and dropped me at the RF&P crossing at Ashland around 11:00 p.m. Not knowing what else to do, but having hiked along railroad tracks before at a rate of about three miles per hour, I figured that I could walk north along the RF&P to Doswell and then west along the C&O to Beaverdam and arrive by daybreak. However, a few blocks north of where I was dropped off, I saw a light in the Ashland taxicab office. It seems that the dispatcher was also the driver of the one-cab company. He agreed to drive me to Beaverdam for $20. I was willing to pay much more than that since I didn’t want to be a no-show for my first assignment. About 45 minutes later, we pulled alongside the depot. The C&O had not issued a switch key to me, but I had a Southern Railway key I had purchased off of a railroadiana list which I knew would fit into the C&O lock keyway. I let myself in through the freight room door with a huge sigh of relief. Soon thereafter, I fell asleep on a trackside waiting room bench, which I would use for several other overnight stays.

Richmond City

Q Office

Q Office was a teletype relay office on the top floor of the First National Bank Building at Ninth and East Main Streets. The Richmond Division Superintendent’s and General Manager’s offices were one floor below. I was not proficient at teletype then but given enough time I could create or relay a message using punched tape. I only worked at that office once and the Chief Dispatcher’s office must have been scraping the bottom of the barrel with no other alternative than to send me. Fortunately, the 11:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m. shift was slow and mainly consisted of receiving morning report messages for the officers and recording these transmissions.

There were trunk line telegraph wires between Richmond, Washington, Newport News, Clifton Forge, Huntington, Cincinnati, and Cleveland. There may have been others that I don’t recall or fail to remember. The most important responsibility of the office shortly after midnight was to send a message to each of the other relay offices. It read something like this:

CHARVAT July 11, 1971 12:05 AM 18 SENT 24 RECEIVED GN&GM RICHVAT

I may not recall the teletype addresses such as CHARVAT correctly, but that particular one is CHARlottesville VA Teletype. The “GN&GM” greeting was the abbreviation for “Good Night and Good Morning;” that brief moment at midnight which closes one day and begins the next.

The purpose of these messages was to confirm that all sent and received were accounted for. If the Charlottesville teletype office had sent a different number of messages to Q Office than 24, or showed receipt of something other than 18 messages, a reconciliation with that office would ensue to determine the discrepancies. During my assignment, everything checked out because the first and second trick operators were more experienced. I don’t recall their names, but believe there were two operators on daylight, one of which was the office manager. The evening shift and night shifts each had one operator. Q was a continuous office.

DO Office

The operator at DO Office occupied a room adjacent to the dispatcher’s office at Main Street Station on the third floor. Seaboard Air Line offices had been on the fourth floor but were vacated shortly after the formation of Seaboard Coast Line in 1967. My understanding is that most of the staff moved to 3200 West Broad Street, formerly Atlantic Coast Line offices within Richmond.

Midway down the third floor hallway, there was a door entrance into the Chief Dispatcher’s office. Walking through that door, the Chief Dispatcher’s desk was facing the door. To the right, as one faced the desk, was a door with a pebbled glass panel with black lettering “Dispatcher’s Office – Strictly Private.” At the end of the hallway was the door into DO Office, staffed 24 hours by teletype operators. I worked there on two occasions, a single evening each time. Furnishings were lean: a desk and a teletype. Main responsibilities were preparing passenger train consists which by 1971 amounted to one passenger train each way between Newport News and Charlottesville. The origin terminal for each train prepared a train consist and unless there was a change at Richmond, the same consist was received as a tape output that could be used for the outbound train report to the next terminal after creating a new header tape with departure time and crew information.

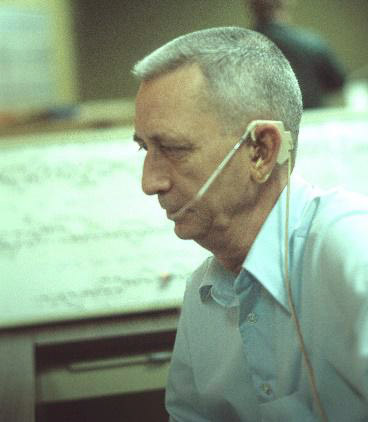

The best aspect of working DO office was the opportunity to meet some the dispatchers who previously I only knew from their voices. Of the group, Wendell Miles was the dispatcher I enjoyed working with most. He had a rich, salubrious voice which evoked images of a handsome Rhett Butler character. When I met him face to face, he had a weathered, lined-face and flat-top-style white hair, accompanying a slender build.

By 1983, the Richmond and Clifton Forge Division dispatchers were relocated to a new building in Fulton, west of downtown Richmond. Jim Pickett, Wendell Miles, and E. E. Scott were relocated to that office within a then state-of-the-art dispatching center. While working for Virginia Electric and Power, I was able to see these familiar faces again after ten years.

John Poindexter was nicknamed “Pointy” by Scotty at R Cabin. Aside from his C&O career, he was said to have liked bargain pricing. In the era before warehouse clubs such as Costco, he bought a case of peanuts at an irresistible price –even though he didn’t eat peanuts.

The “River” dispatchers had a very straightforward job when compared with Piedmont/Peninsula dispatcher. With CTC covering their entire territory, all train movements were visible to and controlled by them. There was double track midway between Bremo and Shores, which was the main location for meeting eastbound coal trains with westbound empty hopper trains. Double track between Westham and Rivanna Junction likewise facilitated movements at the east end of the dispatcher’s territory.

I was assigned to DO for an evening during July 1972. During daytime, the ground floor office door on the west side of Main Street Station was unlocked. After dark, regular employees were issued a door key for entry.

Shortly after midnight after finishing my eight-hour assignment, I rode the elevator to the ground level and exited, with the outside door closing firmly behind me. My car was parked at the corner of the lot generally under the former Seaboard Air Line viaduct which runs along the west side of Main Street station. The area is dark aside from occasional street lights, desolate and not in the best part of town during the early 1970s. I got in my 1965 Dodge Coronet, turned the ignition key, and . . . nothing. Repeated attempts remained futile.

In that era before cell phones, there were no pay phones in sight. I checked the doors for Main Street Station and all were securely shut. I was in a quandary regarding what to do until two policeman walking their beat happened by. I requested their help with much relief because I felt like prey in the silent neighborhood without passing traffic amid abandoned buildings. Fortunately, one of the officers was a backyard mechanic and after raising the hood, adjusted the carburetor with a pocketknife. After some tinkering, the engine started and ran, allowing me to drive back to Charlottesville. I owed him a debt of gratitude and don’t think I expressed it enough aside from many thank-you’s as I prepared to head west along Main Street toward Interstate 64.

R Cabin

During 1972 and 1973 summers, I worked at R Cabin more often than any other relief assignment. R Cabin was formerly a mechanical interlocking tower that controlled switches and signals at the west end throat of Fulton Yard. During the 1940s, a Union Switch and Signal Centralized Traffic Control (CTC) machine was installed so that its western limit was Rivanna Junction and its eastern control point was a westbound home signal near the Darbytown Road crossing. That location was the east end yard limits of Fulton yard. Between R Cabin and Rivanna Junction were signals at “Coney Island” which included a turnout that went to the Church Hill tunnel. This tunnel was the early entry to Richmond before Main Street Station and the viaduct were constructed. The eastern portion of the tunnel remained open as a tail-track for a yard engine to handle a cut of up to twenty cars to the Southern Railway interchange track. Coney Island was a hill with the viaducts extending from either side and was visible along Virginia Route 5 after the east end of Main Street crested and descended towards Fulton Bottom. This area had the Richmond Gas Works tanks, all defunct by the 1970s. The eastbound home signal to R Cabin interlocking was on Coney Island.

R Cabin worked as much with the Fulton yardmaster as it did with the Peninsula and Piedmont Dispatcher. There was an intercom box with the yardmaster. A large plate-glass window was on the east side of the tower allowing a wide view of the Fulton Yard west end throat. The yardmaster advised R Cabin’s operator about freight trains departures as well as other yard movements since the R Cabin interlocking was within the yard limits. The CTC machine was L-shaped with the left leg controlling trackage between R interlocking and Rivanna Junctions, which was to the right of the operator when facing the machine.

There was no train order signal at R Cabin because all trains originating at Fulton Yard required a clearance card. There were usually several train orders on top of the CTC cabinet, usually slow orders for the Rivanna and Piedmont Subdivisions. The Peninsula Subdivision was CTC controlled by the Piedmont-Peninsula Dispatcher, so no clearance card was required for trains heading east from Richmond. The conductor for westbound freight trains would drive to the base of R Cabin and honk the car horn before driving to the yard for their train. The operator would toss down the conductor’s and engineer’s clearance cards accompanied by any required train orders or messages. The operator would prepare a clearance card for a train about an hour prior to its departure; the retrieval by the conductor was about a half-hour later.

All freight trains operating westbound to the Piedmont Subdivision at Rivanna Junction required a “run extra” order and sometimes a “time order.” The “run extra” order was similar to the one I’ve described for G Cabin. When there was a first class or previously-ordered eastbound freight train on the Piedmont Subdivision, the time order read:

C&E Extra #### [Lead locomotive number] West Extra #### wait at Hanover 10:05 AM Doswell 10:30 AM Beaverdam 11:00 AM Frederick Hall 11:30 AM Mineral 11:45 AM Louisa 12:01 PM Gordonsville 12:30 PM J.L.P.

This wording may not be precisely accurate since I don’t have a copy of an order for reference. According to this order, the train was not to pass the westbound passing siding turnout at these stations prior to specified times so that a later meet order could be issued. Piedmont Subdivision train orders were issued jointly to G Cabin, DO Office, and R Cabin. R Cabin had the dispatcher’s line on a loudspeaker, so the dispatcher usually had to say “R Cabin” with the operator responding “R Cabin.” If there wasn’t an immediate response, the dispatcher rang the R Cabin selector, just as he would have if DO or G didn’t answer. When all three operators were on the line, the dispatcher started with the office handling the originating train, such as “R Cabin copy three; DO copy three; G Cabin copy three.” G Cabin would set its eastward train order signal to display yellow, then responded “Yellow East, G.” DO and R Cabin did not have train order signals so those operators responded “NS DO” and “NS R.” After the order was issued, each operator repeated the order in the sequence that they were originally addressed. After all operators properly repeated the order, the dispatcher said “Make it complete at [time],” with each operator replying “Complete” and their initials.

Regarding the time order, there was rarely an opposing train on the Piedmont Subdivision between Sandco and Gordonsville. My recollection is that the dispatcher set up the order since there was no train schedule for an extra. This was automatic block signal territory and the times in the order were typically about five or so minutes before that of a train’s usual running time between station locations, so that basically the train could run at maximum authorized speed. The order gave the dispatcher the ability to later issue an order at Beaverdam, Mineral, or Louisa if there was an unforeseen movement in the opposite direction or there was a track condition that arose requiring a slow order. That’s how I remember it—at least during the 1970s when train frequency had diminished.

Since yard switching was a continuous activity except for about an hour during each shift change, the westbound dwarf signals from each of the two switching leads were designed to show restricting automatically after a yard engine returned past the signal. There was usually one engine and sometimes two that were “drilling” cars into the classification tracks.

The Peninsula Sub-Division was double track during the 1970s from Rivanna Junction to XA Cabin at Newport News. Although the dispatcher had several control points, trains operated with the current of traffic according to Rule 251; that is, eastbound along Track One and westbound on Track Two. The Piedmont-Peninsula dispatcher would notify the R Cabin operator of a westbound freight train as it passed Providence Forge station. When passenger trains were on schedule, there was no alert either eastbound or westbound. I overlooked lining up for a westbound Amtrak train at the Darbytown Road home signal and received a call on the trackside phone from the engineer. I never made that error again, usually lining up for the passenger move a half-hour in advance so I would not forget if other activities distracted me. The same was true at G Cabin; I lined up from Charlottesville to Massie for Train 2 and Orange to Gordonsville for Train 1 well in advance.

R Cabin had a hot-box detector reader for a unit at Westham. As a train passed, a tape ran showing straight two parallel lines representing each rail and bumps for each passing journal. If all of the bumps were a similar height, the journals were running cool, although the bump for a roller bearing was slightly warmer than those with friction bearings. If there was an unusually high reading for one of the journals, the Rivanna dispatcher was notified who stopped a westbound train near Sabot or an eastbound train near the Tredegar Iron Works before the train started onto the James River Viaduct. The R Cabin operator would count the bumps from the head or rear of the train –whichever was shorter—and advise “high reading, North (or South) rail, ## axles from the front (or rear).”

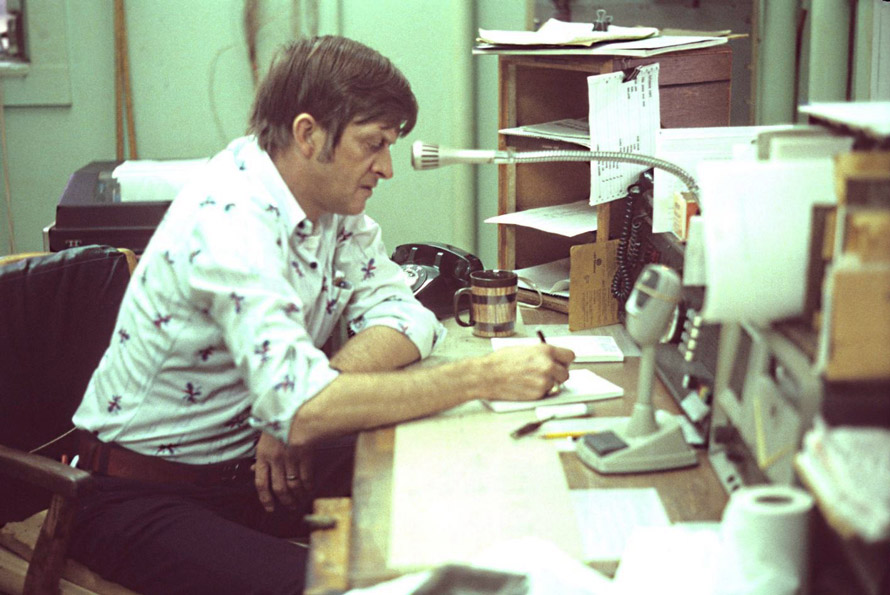

There were three regular operators: E. E. “Scotty” Scott, daylight; Lawrence R. “Larry” Wright, evening; and Kenneth “Kenny” Bryant, night. The swing operator position had become vacant and the C&O asked me to post the tower for training during June 1972. Another fellow in his 50s from another railroad was also training; both of us were together during first trick one afternoon with Scotty. At 4 PM, the other fellow suggested that we go to the Jade Garden on West Broad Street for dinner. I picked up the tab, figuring he’d reciprocate on another occasion. That was the last I saw him; Larry later mentioned that he became frazzled during an evening with him and quit. R Cabin was hectic at times but I never considered it to be difficult. Several other relief operators didn’t choose to train at R Cabin, so I had a full schedule of assignments for 1972 and 1973 summers.

Dr. Frank R. Scheer – Photographs and text Copyright 2018

Join us next month for Part Three of this Three-Part story, which will cover the Chesapeake & Ohio's Peninsula, Rivanna and Virginia Air Lines Subdivisions.

Wonderful! I enjoyed the text and I love photos of old depots. neat writing and pictures. Keep up the great work. Thanks for posting all your photos and text!!

Dr. Scheer, this is masterful. The stories about the operators and dispatcher make everything come alive and capture the wonderful, human industry that railroading used to be. Much has been lost with the elimination of towers and stations in the name of progress. Thank you for writing this so eloquently.

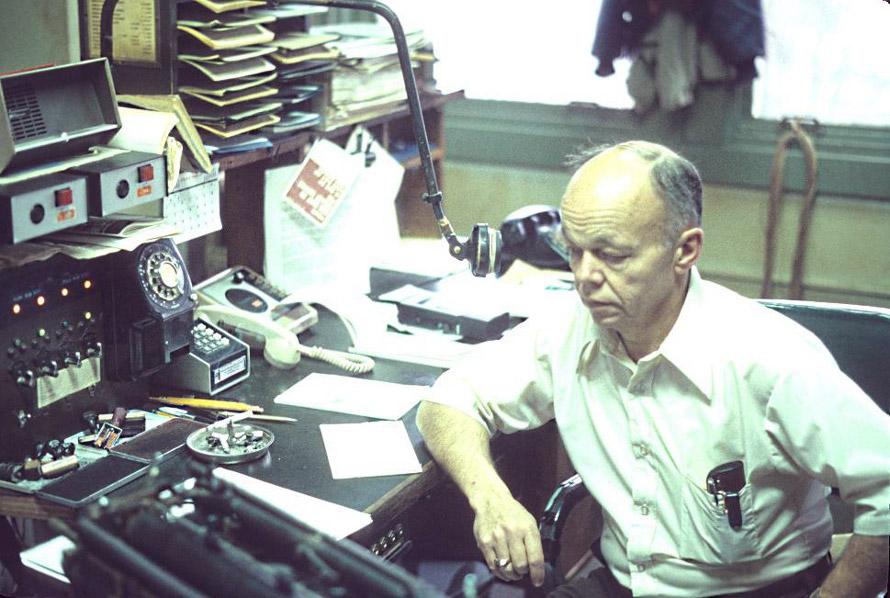

Hello, Frank. I very much enjoyed reading your memories and seeing the photos. Fulton Yard’s R Cabin was the first job I trained on when I went to work there in 1982. I knew E. E. Scott well, though by that time he held a job in the general office building. The photo shows him actually working at what was known as “new” R Cabin, built in the 1950s to supplant “old” R Cabin, which is pictured. New R Cabin was demolished long ago, much sooner than old R Cabin. Old R Cabin was demolished during my last years at Fulton, 2008 to 2015. I took a whole series of photos from the beginning to the end.

Although I have no special interest in the C&O or Virginia railroads, and doubt I will ever set foot in the state, I found the information and phots presented here to be absorbing. I wish that something similar could be done for every part of the country. And Canada, too! Take that as a challenge, if you wish . . .