John Sanderson is a New York City based photographer whose work has appeared in Railroad Heritage , Trains , BBC News , Slate , Wall Street Journal, the Oxford American magazine and numerous other print and online publications. His work has been shown widely in both group and solo exhibitions, including “Railroad Landscapes” a major solo exhibition at the New York Transit Museum in Brooklyn, New York. John was the recipient of the Center for Railroad Photography & Art Docent Scholarship award in 2013 and 2015 and he was a featured speaker at the Center’s 2016 Conference. Visit John’s website to learn more.

Edd Fuller , Editor , The Trackside Photographer – John, I have followed your work for several years and have been looking forward to the opportunity to talk with you about it. Your photographic approach to railroads as part of a broader visual and cultural landscape really resonates with the ideas behind The Trackside Photographer. Tell us how you got started as a photographer.

John Sanderson – Hello Edd. First off I want to thank you for the interview. I am a long time fan of The Trackside Photographer. I began taking pictures at fifteen with a 35mm film camera. Our family friend Ivan Shaw was the photo editor at Vogue Magazine for many years and he encouraged me to pursue photography. If he saw something in my work, I must be on to something. At first I played around with a point & shoot and then moved onto a Minolta SLR. This early work was a return to the memory of time spent with my father exploring the northeast United States. My photography grew from there.

Edd – I can’t find it now, but I read somewhere that you started to realize what you wanted a photograph to be when you began working with large format cameras. How did you come to work with large format film in this digital age.

John – Film photography is where I started. This was around 1998 when digital was coming on the scene. It was a natural progression for many photographers in the film days to begin with 35mm and move to other formats depending on how their style was developing. Since I was landscape oriented, everyone from a mentor in high school to a Great Plains rail photographer named Kent Staubus nudged me to try large format. Kent sent me some of his 4 x 5 in. slides in the mail. Seeing his film quality blew me away. I was sad I had to send them back!

My first large format camera was a Horseman L. It was a heavy monorail camera which was difficult to transport. It was great to learn with because it has full camera movements (all the special tools that allow you to control perspective and sharpness) and was very precise. After that I worked with an Ebony field camera because I was doing long walking trips around New York City and needed light-weight. Now I work with an Arca Swiss F- Line, it is also a monorail camera but is quite light and portable. It does everything I need. My traveling equipment still consists of three large camera bags, two tripods, and a collapsible ladder. Not light by any means.

Edd – Tell us about your working method in the field, and what shooting large format film brings to the process.

John – Because of the slower process, it encourages me to stick around and let the experience of weather, light and mood really sink in. I’ll dwell there until I feel the picture is just right. Then I’ll make one, two or at most three exposures and set off to the next location. Because the camera is unusual to most, strangers will often approach and start up a conversation. This often leads to greater insight into the area I’m working in. Just recently I was in Lewistown, Pennsylvania with fellow photographer Yoav Friedlander (we were shooting material for the Rust Belt Biennial). As we were shooting a building a man came up and asked us about our project. He lead us to another site which yielded some excellent photographs. He also gave us insight into the town’s history and economic decline.

I’ll take a picture of anything that intrigues me and figure out later on what it means . . .

Edd – I am guessing from your work that your artistic antecedents are not necessarily associated with railroads. Who are some of the artists and photographers who influenced and inspired you along the way?

John – My older sister Laurie took the initiative to expose me to art at an early age. We’d go to the big museums in New York City. Pieter Bruegel the Elder remains vivid in my mind since I saw his paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His expansive world landscape paintings inform me to this day. I can see his influence when I seek out an elevated viewpoint in order to render all the little details which communicate a sense of place. Our visits to the museums also exposed me to the work of Caspar David Friedrich. The mood he set in his paintings, often including figures gazing out into a weathered scene, resonated with me. I also liked the subjects he chose: scraggly trees, ruins and crashing seas. Painters have influenced me to a huge degree up through the 20th century with American modernists such as Burchfield, Sheeler and Edward Hopper. The history of painting has influenced me as much as photography.

Edd – Aside from railroad subjects, what kinds of things draw your eye?

John – I’ll take a picture of anything that intrigues me and figure out later on what it means, or what potential project it fits into. One new project developing now is called Carbon County. It’s work from Wyoming taken in 2017 when I worked as photographer at Brush Creek Ranch.

Edd – Regardless of the subject, your style is remarkably consistent. Can you share one of your photographs that is not related to railroads and tell us a bit about it?

John – The photograph Explorers, Egmont Key, Florida is an image that has stood out to me in the last few years. I rarely make portraits, and when I do it’s often because the surroundings resonate with the subject. Context remains a guiding force even when photographing people. I had set up the 8 x 10 camera to photograph the blue structure, a coastal artillery battery from the Endicott Period, but I felt something was missing. I decided to include people in the scene. I waited for about an hour until the right subjects came by, four boys who were exploring the empty structures. Their experience resonated with the memory of my childhood. As an interesting aside, there are a set of twins in the picture, at the time we were expecting twin boys, who would be born three months later.

Edd – Well, we have to get to it sooner or later, so let’s talk railroad. How did you become interested in railroads? Did railroads spark you interest in photography, or was it the other way around?

John – It started with the rails. As a boy I had O-Gauge electric trains and an eight-by-ten foot board to run them on. My dad built it. We also took family road trips around the northeast including visits to Scranton and the Strasburg Railroad in Pennsylvania. When I first explored Scranton with dad in the late 1980s it was before the Lackawanna Railroad shops were restored into Steamtown National Historic Site. The Union Pacific Big Boy was there, but the old locomotive shops were falling apart. It’s vivid in my memory, the smell of creosote and oil. The crisp winter air. We walked over earth blackened from years of coal and oil deposits. Yet among all this were small trees and grasses sprouting up through the empty tracks and roundhouse structures. These sensory experiences of place continue to inform the work I do, as does exploring the balance between the built and natural environment.

My early work with 35mm was a return to many of the locations I visited with my father back then. He had passed away a year before I began photography. As I developed from that early work, I branched out into other subjects, yet the memory of those early days are still with me.

Edd – Among railroad photographers, whom do you admire?

John – At first it was O. Winston Link. I saw his work in book form, and later the prints at Robert Mann Gallery. What stuck with me was the nuance of his scenes, how he was able to photograph the railroad without actually making it the central subject of the image. The trains were ancillary, but at the same a motif underscoring every picture. It was only after when I discovered Carleton Watkins and William H. Rau, whose work focused on the railroad landscape at a time when the construction of railroad, rather than the trains themselves, was the biggest feat. As I begin looking to contemporary work, the photographs of Jeff Brouws, and later Michael Froio were important. I give them also my deepest thanks for having been great resources in helping me pursue these projects.

Edd – In your own work, why no trains?

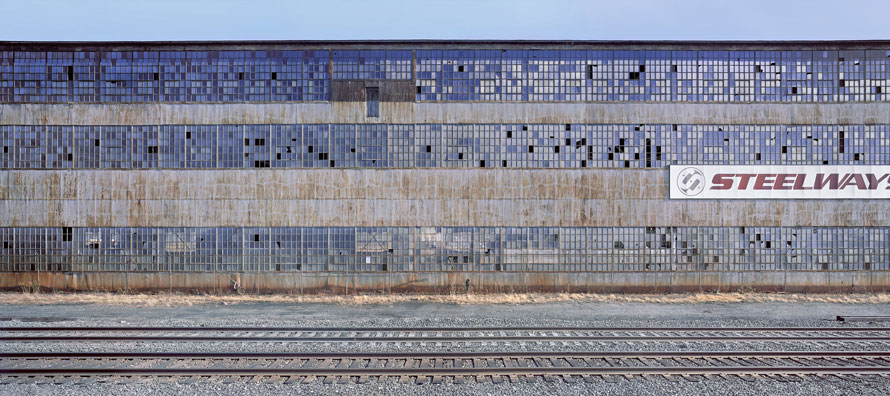

John – I’d have to compose differently to adjust for a train. If you look at an image like Steelways Shipyard , the camera is positioned in such a way a train would obliterate the gesture of tracks as well as the building. The empty tracks also remove the picture from being about the train, and instead it becomes about the environment. This is important to the work I do in the Railroad Landscapes project.

I enjoy going into the unknown and leaving the process of photographing as open-ended as possible. One must be open to surprises.

There was also a style of railroad photography that began around 2000 with a photographer named Brian Plant. He often posted on various railroad photography forums and published in magazines at the time. His images were captivating. His style was to photograph the approaching train’s lights

illuminating its surroundings. If he could do that so well, I said to myself why not take it to the extreme and leave the train out entirely?

Edd – More than trains and railroad structures, the tracks themselves are often the key ingredient in your compositions. Why tracks, and how do they function in your photographs?

John – It’s interesting to explore how the tracks interact visually within various environments. Some gesture outward from the camera and others cross the frame horizontally. Because the surrounding environment often determines the picture, the railroad often falls curiously into the scene. I really enjoy that understated presence. They are also a visual motif connecting each picture, which is important in the overall structure of the project. Throughout the series you will see various angles and perspectives of the tracks. I like to think each one has a different feeling.

Edd – How do you choose locations, and decide what you will shoot? I picture this as being a pretty deliberate process, particularly when working with large format cameras. Do you research and scout locations in advance, or depend more on serendipity?

John – Most of my work outside New York has been taken on two week to month-long road trips. I waypoint specific locations when planning a trip, however, the most interesting photographs and locations are often discovered while en route to these destinations. Because I like to photograph in various light conditions, I will be working all day and make up driving time during the night. That said, I enjoy going into the unknown and leaving the process of photographing as open-ended as possible. One must be open to surprises. It is indeed a combination of research and serendipity.

Edd – What is it about a place or a scene that draws you in, that makes you want to take a picture?

John – It’s that feeling in your bones. You see something you can’t say no to picturing it. A lot of this is working on the subconscious level. Much of what dictates the decision is light and weather conditions. If you look at the image below from Oklahoma, the sky is completely clear. The image worked because of the luminance of the building was so bright that the shadows are completely open despite being totally back-lit. This isn’t something I could have planned, but I had to be there to experience.

Edd – “Railroad Landscapes” is a long term project that has in some ways defined your work and opened many doors for you. How did this project come about? Did you know what you wanted going in, or did the project take shape as you explored.

John – It came out of photographing trains along the Hudson River and Pennsylvania during my teenage years when I was teaching myself photography. There was no epiphanic moment where I decided to do this project, but I just kept making photographs and the project evolved and started to take up more of my energy. I decided early on that I didn’t want to just photograph abandoned rail lines, but places which are still active. The environment might be abandoned, but trains still run by.

Edd – Railfans tend to look at photographs for what they tell us about railroads, but I think in your photographs, we see what the railroad tells us about America. The railroad has played a major role in the cultural, economic and political landscape of this country. How does that history come into play when you are photographing railroad subjects?

John – I am not only picturing buildings, tracks and landscapes but also the status the railroad has achieved in American society. Antiquated, old, no longer relevant are ideas arising around the subject. I want to go beyond that. The number of railroad companies was once in the hundreds. All those smaller roads have merged into a few larger corporations. What remains are the corridors set forth during the formative stages of this country, and while some are still busy with trains and others are abandoned, throughout the emptiness is a void the viewer can fill. Railroad companies have come and gone, but our collective experience of the railroad as a shared place has remained. The tracks are akin to this man made river that led to ambitions as great as the transcontinental railroad or as low as the destruction of

Penn Station. It’s there where I search for meaning.

Edd – When I look at this work, I think of Walker Evans and his concept of “lyric documentary.” “Railroad Landscapes” can be seen as documentary, but it is poetic at the same time. How do you see the relationship between the documentary and the poetic, and how does this relationship inform your work?

John – There is an inseparable counterpoint between the two. Escaping the vestigial element of the railroad landscape is impossible. Some of these locations were once of greater economic and social relevance. The passage of time has rarefied these places. This is the documentary. I’m not impartial

enough with the subject to claim myself as a documentarian. Through photographing and printing I impart a lot of my own creative impulse into the final image. This is the poetic, or lyric. When making a picture, it’s a hard line between over-sentimentalizing and waxing nostalgia. You can’t really “shoot poetically” and get away with it because the result will end up generalizing the mood of the scene. In letting the subject speak for itself, the poetic, or lyric aspect enters the image. This is why Evan’s work is so poignant.

Edd – What are the greatest challenges that you face as you continue to grow as a photographer.

John – The greatest challenge is finding the resources to continue to exhibit and get the work out there. It is an expensive endeavor and I am always looking for support to continue the work. I have to give thanks to organizations such as the Center for Railroad Photography & Art and the New York Transit Museum as well as those individuals who have supported me through the years.

I like to see the artist searching for meaning in picture to picture. That takes me on a journey.

Edd – What do your photographs say about you as a person?

John — I am on the move and never content with what I’ve got. It’s part of being an American; the restlessness. Thomas Wolfe said it well when he wrote that “Perhaps this is our strange and haunting paradox here in America—that we are fixed and certain only when we are in movement.” When looking at a photographs I like to see the artist searching for meaning in picture to picture. That takes me on a journey. I hope these qualities come across in my work.

Secondly, I’m an American. Examining our collective history and the necessity to document the places we inhabit as a society underpins what I do. Having ancestors who fought in the American Revolution and Civil War, I’ve inherited a strong bond to the land. I grew up with John Ford’s Westerns playing on my father’s TV set, the faint sound of a baseball game emanating from the radio, and eating hotcakes at McDonald’s. All this stuff informs what I’m attracted to in pictures, from urban to rural, suburban to industrial. There’s a story everywhere.

Edd – Where do you go from here? Any new projects or ideas that you would like to pursue?

John – I am going to photograph from the Pacific Northwest to Texas to gain a more holistic rendering for my projects. Along the way I will collect more streamliners for the Locomotive series. It’s my return to photographing trains.

Edd – I think one of the keys to your success has been your consistent style and vision across a broad range of work. What advice would you have for a photographer just starting out, and looking for his own voice.

John – Work hard and absorb a lot of other artwork: photographs, paintings, music, literature. Let it all sink in and find a community to support you. When I was first starting out I can remember being frustrated and blocked. I often thought I have nothing to add to the medium. I kept making work until themes began surfacing in various pictures, which then became connected. I passed through all that mess to find something that calls out to me. I could not foresee this developing. My advice is to just go out there and make the work. Look at your pictures in aggregate and you will start to develop your voice. One thing is certain, this process cannot be rushed. Follow your intuition and let it develop organically.

Edd – And one final question. You have traveled widely in pursuit of your vision and must have many interesting stories to tell. Is there an experience, either good or bad, that stands out in you memory?

John – It was 2015. My day began early with photography across South Dakota of Railroad Landscapes—grain silos, small towns, lone trees against the vast expanse of the Great Plains. I was on the road to Wyoming. I had mapped out the location of locomotives along the way. Actually I had been planning to photograph this particular one for over a year because of its unique placement in the landscape. I planned to arrive here in late afternoon to catch light on the nose of the engine. I felt the day was pretty fruitful so far—but as I began my final approach to photograph this locomotive, I encountered some nasty weather. Driving along I-90 the sky darkened dramatically, everything was near pitch-black as rain came down in buckets and traffic on the interstate decreased to a snail’s pace. I was resigned to my fate. I didn’t think I’d make it there before dusk.

The sky was still very dark and rain continued to fall as I closed in on the town of Murdo, South Dakota. I gave up photographing the streamliner. I didn’t want to risk rain damage to the large format lenses so I began working with the medium format on other subjects. Suddenly the rain stopped and the sky began to break apart in the West, where the sun was falling. Light! I saw an opportunity, grabbed my 8 x 10 camera and placed it in front of the locomotive. I shot one sheet out of fear; having traveled this far from New York I didn’t want to leave here without something , even if it’s not perfect. I waited longer but time was running out. After praying to St. Ansel, the sky cleared again and this is what unfolded in front of me.

Edd – John, thanks so much for talking with us. Your work is an inspiration and I wish you the best of luck as you continue to travel down the road you are on. I can’t wait to see where that road leads!

John – Thank you for the opportunity and for running The Trackside Photographer.