Part Two

Standard 60‑Foot Full RPO Car (1928)

All 60‑foot RPO cars built after 1912 were of all‑steel construction. These cars were used for the distribution and handling of mail only; the interior had built‑in letter cases and pouch and paper racks, plus overhead boxes.

The cars were heated by steam heat, with long protected steam pipes along the baseboard on each side of the car, except near the doorways where there were large upright protected radiators. During the advance distribution of the mail at the initial terminal, the car’s steam line was connected to permanent terminal steam lines, when needed. En route, the steam was furnished by the locomotive, whether it was diesel or steam powered.

There was a clothes closet in one corner at the letter case end of the car, across the car from a semi‑private flush toilet, and swing-down wash basin. (In later years, the toilet and wash basin were enclosed.) The water was provided by a large cylindrical storage tank, suspended across the car below the ceiling. This tank was filled from the outside of the car. The train steam line was connected to the water supply at the wash basin, for heating the water. By turning the water off and the steam on, it was possible to make coffee and heat food for lunch. There was also an iced water cooler at that end of the car; it was iced en route when coolers in the passenger cars were iced.

Even with the ceiling fans on and running with the doors open, the sun’s shining on the all‑steel car in the summer time made it quite hot. In later years, folding iron gates were installed in the four doorways, as a precaution against losing mail out of the door while en route. Still later, a few cars were equipped with air conditioning, although generally it wasn’t practical.

There were also a signal cord and an air brake cord in all cars. About the only time the signal cord was used was for flag stops, when fragile mail was to be dispatched; this occurred mostly on local runs, before there was alternate service for fragile mail. After the engineer gave one long whistle for the station, the signal cord was pulled three times, just as train crews did when there were passengers for flag stop stations. The engineer would answer the signal with three train whistles, indicating he would stop. The air brake line was pulled only in extreme emergencies, as it applied the air brakes, locking all wheels of the train.

Mail Cranes

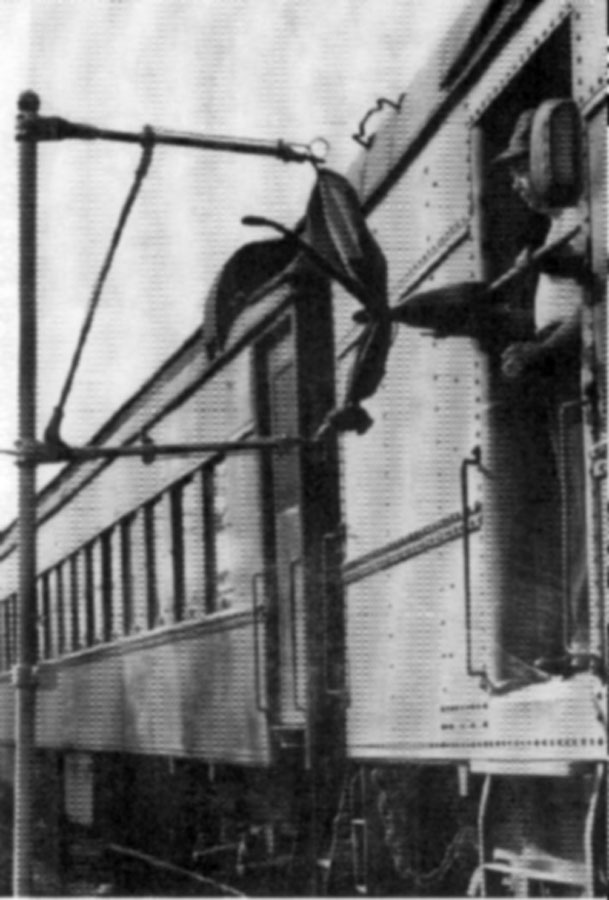

Starting in 1869, railroad companies installed mail cranes for the exchange of non‑fragile mail at non‑stop stations. There were two arms on the crane, the upper arm pointing up and the lower arm pointing down when not in use. There was a swivel pin at the end of each arm, where the catcher pouch was attached. These arms were folded parallel toward the track when the pouch was hung, the spring tension of the arms holding the pouch about three feet from the side of the train. As soon as the pouch was caught, the arms sprang back to their original position. The crane had to be installed in perfect alignment, as to its height and its distance from the track.

If the exchange was made after dark, a lighted lantern was hung on the crane. It was the duty of the mail messenger who carried the mail between the post office and the station to witness the exchange. It was the engineer’s duty to give a station whistle (one long), allowing the clerk time to get to the door. A good “local clerk” had his own landmarks or sounds and did not depend on the engineer’s whistle. In later years, safety goggles were provided to clerks making local exchanges. Thousands of these exchanges were made each day by the RPOs.

Catcher pouches were subject to very hard use, both by being thrown from the train when dispatching and by being caught from the crane. They were made of very heavy canvas, reinforced with leather on both ends, where there were large iron rings for attaching the pouch to the crane. The mail was equally divided in the pouch and a strap in the center was drawn tight; that was the point at which the end of the catcher arm first made contact. The pouch was hung on the crane in an upside‑down position.

Average Day of RPO Clerks

A RPO clerk’s position was unique in that so many of the necessary tasks demanded of him could not be accomplished while he was on duty, and, therefore, had to be performed at the clerk’s home or at a terminal of his run, while he was off duty.

General orders were received each week from the Chief Clerk’s (District Superintendent’s) office; these contained corrections to the state schemes, schedules, and the Postal Laws & Regulations. Schemes, schedules, and PL&R had to be maintained correctly at all times. In some cases, depending on a clerk’s study assignment, general orders were received from as many as three divisions.

Studying for examinations, especially case exams, and going to the Chief Clerk’s office to take exams had to be accomplished on the clerk’s own time.

Printed letter slips, and pouch and paper labels (strips containing five labels), were requisitioned by the senior clerk on the assignment. After printing, the Chief Clerk’s office would divide the total amount of each equally among the clerks on the assignment. Upon receiving the letter slips, they were “run out” in the order that the clerk placed them in the letter case of the RPO. (Slips in each pile were identical and uncollated, and one to three slips from each pile were needed each trip.) Strip labels were “run out” the same way.

Every slip or label used had to be stamped by the clerk, bearing the name of the RPO, train number, date, and clerk’s name. In case of error, this made it easy to place responsibility.

The clerk who handled registers self‑addressed the register receipts to his home, where they were later checked to ensure that a receipt was received for every register handled.

Clerks‑in‑charge had to make pouch records (a list of all the pouches due to be received and dispatched each trip), which were checked each day for irregularities.

All clerks were required to read their Chief Clerk’s order book at the terminals of their run before reporting to work at the postal car.

For this time spent while off duty, a RPO clerk was given one hour and forty minutes each working day, making his average work day six hours and twenty minutes instead of eight hours. His layoff was based on the number of trips his assignment was due to make each week, and the amount of time involved in each round trip. Some assignments had up to four hours advance time before the train was due to leave.

40 Years of Changes

| 1928 | 1968 | |

|---|---|---|

| Work Week | 48 hours | 40 hours |

| Clerk's Salary | $2,450 | $7,708 |

| Annual Leave | 15 days | 26 days |

| Sick Leave | 10 days | 13 days |

| Travel Allowance | $3.00/day | $9.00/day |

| Night Differential | 10% | 10% |

| Holidays | 7 | 7 |

| Overtime Pay | Regular rate | Time-and-a-half |

Interesting RPO Information

Clerks‑in‑charge of RPOs had to have stamps available, in case they were needed by the public. Stamps on letters mailed at the postal car or at depot letter boxes were canceled by a hand postmarker, showing the name of the RPO, the train number, and the date.

The shortest RPO was the 10‑1/2 mile Thurmond, W.Va., & Mt. Hope, W.Va., RPO (Chesapeake & Ohio RWY) which was discontinued in 1949.

The longest RPO was the 1168.9 mile Williston, N.D., & Seattle RPO (Great Northern RR) which had three divisions.

The largest RPO was the New York & Chicago RPO (Western Division) Train 14, which had three full RPO cars with more than 25 clerks, running between Chicago and Cleveland in 1951. This line also had the longest RPO cars (80 feet long), the extra 20 feet being used for storage. The following cities were worked by some of the RPO trains on this line: New York City, Brooklyn, Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Cleveland, Toledo, Detroit, and Chicago.

Clarence R. Wilking – Copyright 2018 – The Railway Mail Service Library

Used with the kind permission of Dr. Frank R. Scheer - Dr. Scheer is the curator of The Railway Mail Service Library, Inc., which is located in the Boyce (Virginia) Depot . Email him at: f_scheer@yahoo.com

Very interesting read.

This has been fascinating to read. I’ve been in a couple of Canadian RPOs at museums but it’s great to have this kind of detail to reference.

Great read!