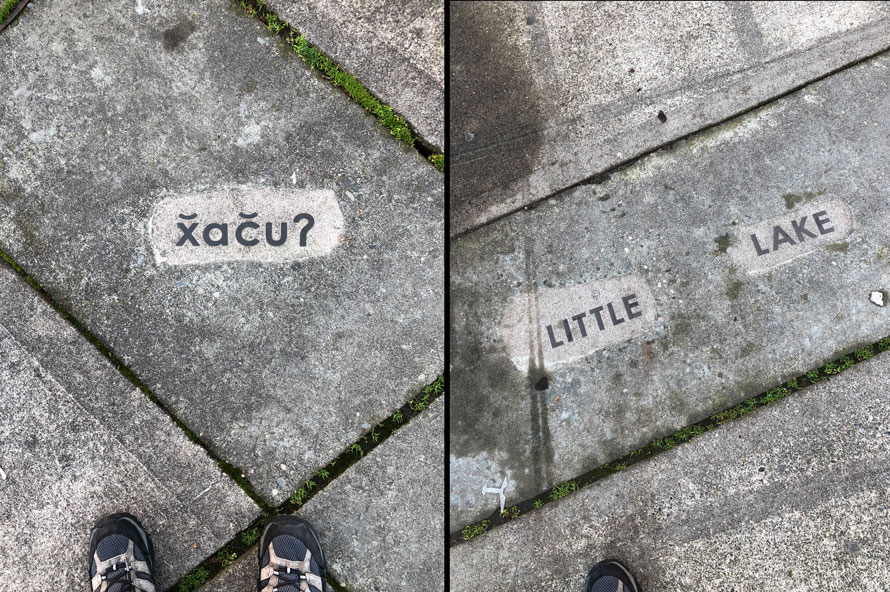

The Indigenous people who lived and thrived on the lakeshore called it Ha-AH-chu, meaning Little Lake. That name is remembered today by a vanishingly small number of speakers of the Duwamish language, Lushootseed. To the settlers and builders who supplanted the first people, it became, and still is, Lake Union. To railroaders, it was Region 4 of the Seattle Division. While that name is lost to time, a work of art remembers lakeshore life and the railroading that once was done there.

From nearly its earliest days, Seattle has been a railroad town. Locally mined coal, locally felled timber, locally produced cedar shingles, and silk fabrics imported from Asia by clipper ship were among the many products that transited the growing metropolis. War and economic boomtimes grew the railroads while economic busts, competitive modes of transportation and, most recently, gentrification have caused the presence of trains to shrink and become virtually invisible.

Seattle’s first railroad was built on the south shore of Lake Union. A narrow gauge operation, it hauled coal. Later, a sprawling coal gasification plant, wedged between shipyards, arose at the north end of the lake, while a tar factory, shipyard dry-docks, a Ford assembly plant and a Navy training installation appeared on the south end. Halfway up the east shore, a man named Boeing opened an airplane parts factory and a float plane base.

Over time, though, the once gritty lakeshore yielded much of its industrial character to growing communities of floating homes (think Sleepless in Seattle) and moorage for pleasure craft ranging from humble runabouts to jaw dropping luxury yachts. What was once a network of switches, sidings and freight houses is now a dense urban core of new apartments and condominiums, tech company offices, hotels and restaurants. Ironically, even as rail in the neighborhood disappeared, light rail was laid for the South Lake Union Trolley, often naughtily referred to by the acronym formed by its initials.

A bicycle and walking path called the Cheshiahud Loop in honor of an Indigenous Duwamish resident of the lakeshore, encircles the lake. On the western shore, the Loop follows the former Northern Pacific right of way. It is there that railroad ghosts are quietly summoned in a work of public art that its creator, Maggie Smith, has called Spur Line.

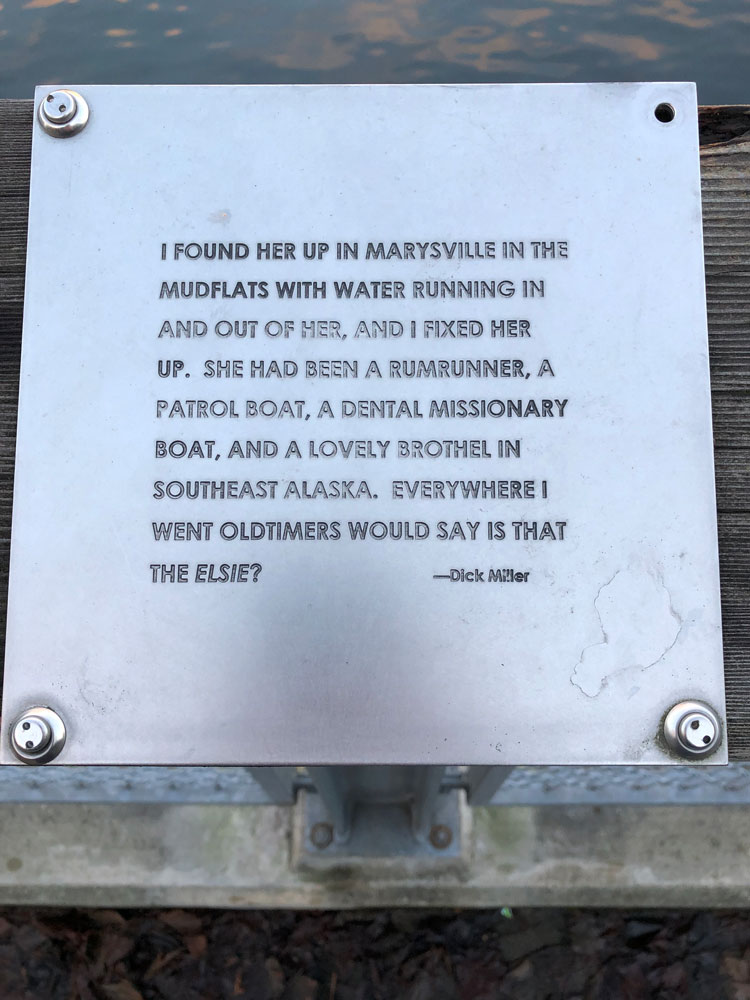

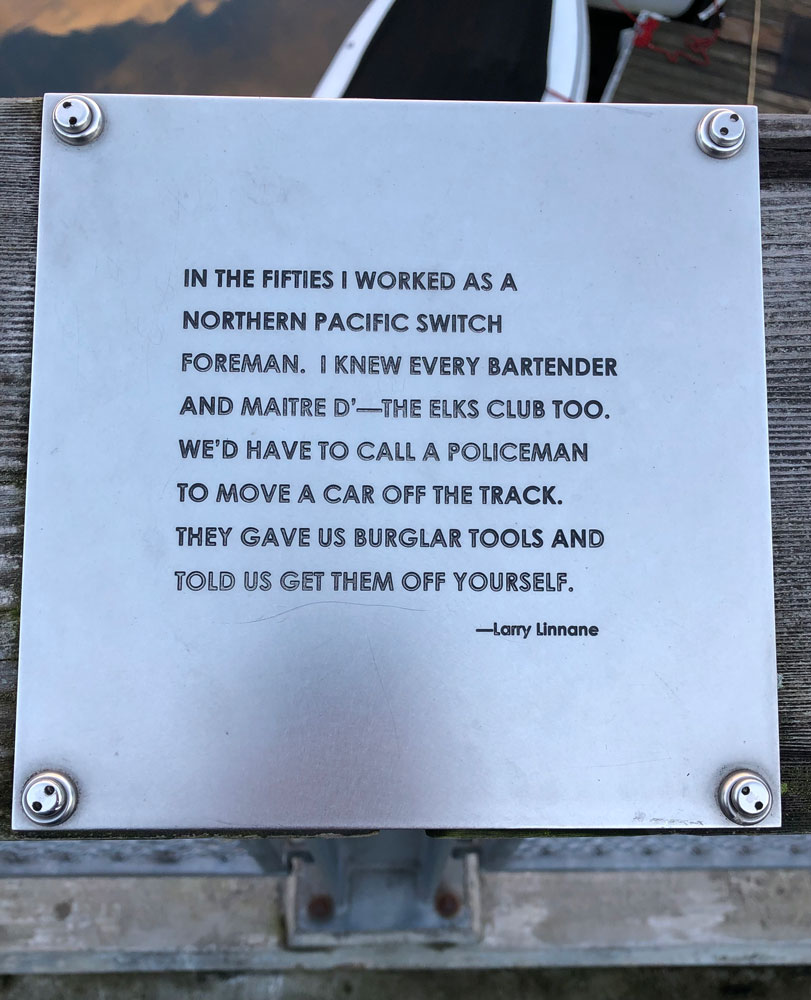

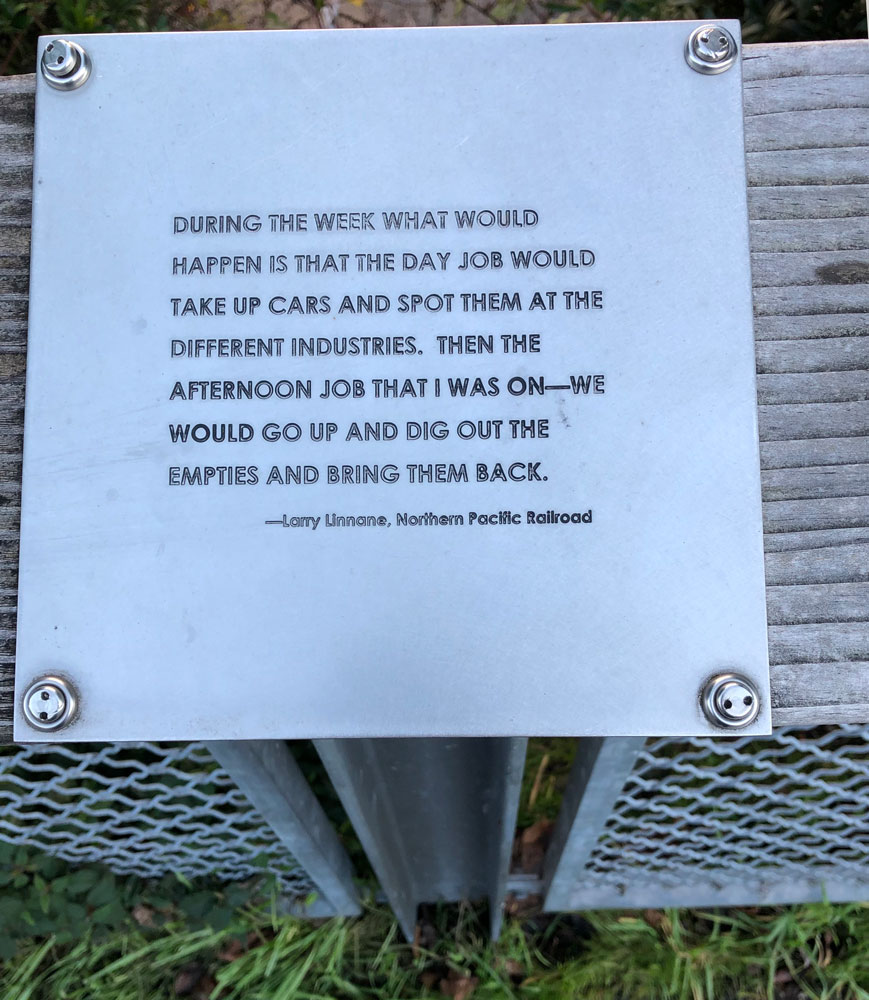

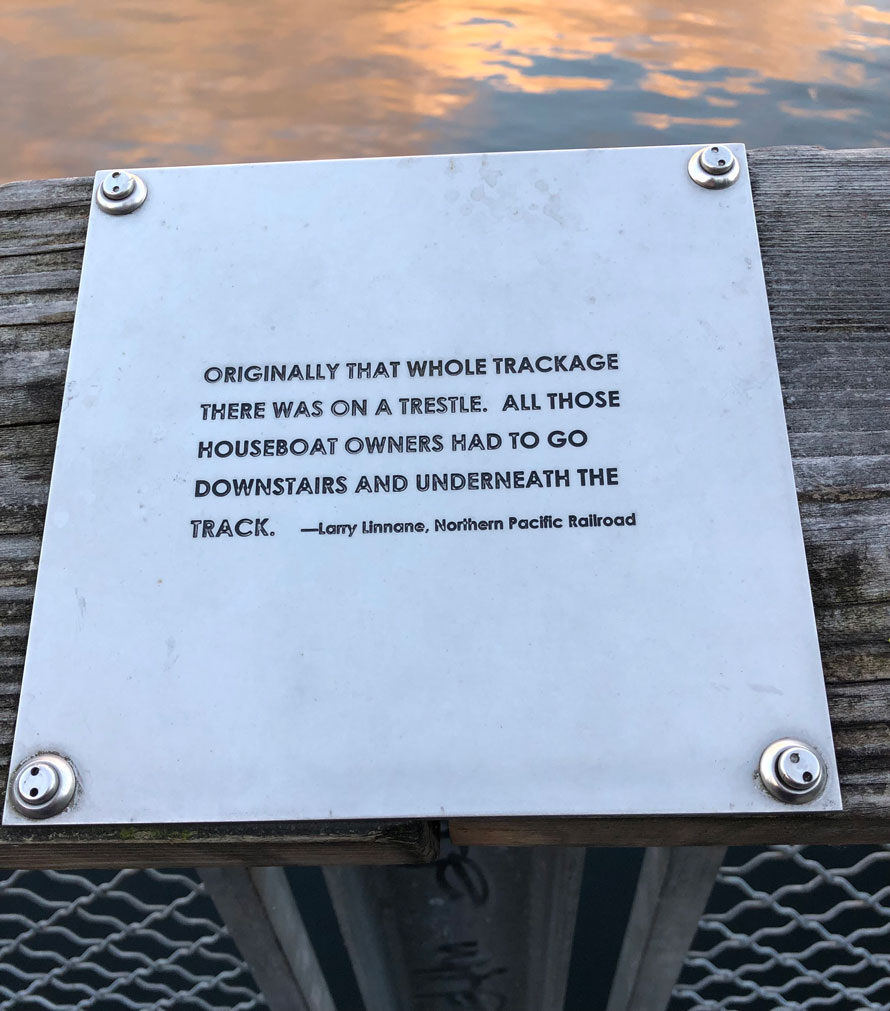

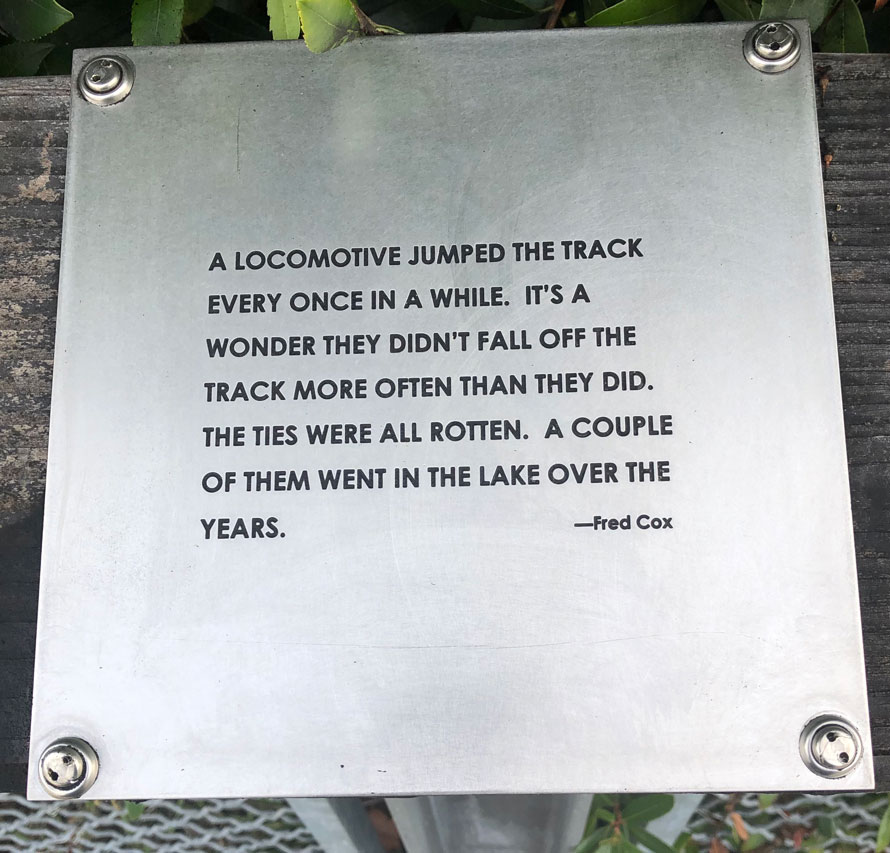

Spur Line’s gentle integration with its surroundings belies more than a century of often rowdy, sprawling competition to use the lakeshore as a place to manufacture and refine, to build or just to live. Spur Line remembers how some houseboat residents had to walk across the tracks or even between pilings under the tracks to leave or come home. It is, in part, about a time when cuts of rail cars waiting to be spotted or taken back to the nearby freight yard blocked access to a lakeside bar, causing thirsty patrons to climb over the couplers to get there. Strong, colorful people lived and worked around the lake—railroaders, boaters, shipwrights and laborers, side by side. Spur Line remembers them.

Look for the beginning of Spur Line as you walk from near the southwest corner of Lake Union. In the space of less than a mile, heading north, you will encounter ten separate locations where Spur Line evokes memory on engraved steel plaques that recount railroad and boating vignettes. Elsewhere, segments of rail are embedded in the pavement, many embellished with references to trains or to the lake. Path-side benches that repurpose old boom logs, tie plates, rails and spikes echo the theme. Even some of the fencing incorporates old rail salvaged from the line.

In a short distance, like the spur line it honors, Spur Line ends without fanfare, even without notice, leaving you to wonder if there are any other signs of the old line to discover. That switch stand on the corner of Mercer and Westlake? Gone. Those team tracks where John Wayne searched for a criminal in the 1974 movie, McQ? Gone. The Terry Avenue Freight House? All gone.

It’s quiet here in the soft, dappled light.

But walk just a little further. Underneath the Aurora Bridge, almost hidden by trees, is a remnant; a few yards of rusted, moss covered track, still resting on decaying pilings. It’s quiet here in the soft, dappled light. In fact, it’s quiet enough that you might still hear the rumbles, creaks and squeals of box cars, flat cars and gondolas being shepherded to and from the lake’s old industries.

You will have to listen with great care, though; the sounds will come to you from a long time ago.

John Mueller – Photographs and text Copyright 2022

The author wishes to thank Maggie Smith, who generously provided insight on how Spur Line developed from original concept to installed public art.

The fine art of preservation exemplified in this work is appreciated. Bring more.

Just as the information, memories and stories bring life on the railroad, the people and place in history, in the Dispatchers, so this open book speaks profoundly.

I could hear the sound of the coupler opening and the brake hose coming apart after the brakemen tied the hand brake down, also the groans of the wheels as the cars were moved! Great job!

Many thanks, John. Coming from such a skilled and knowledgeable railroader and writer, your comments mean a lot to me.