Prologue

On a crisp July afternoon in 2012, I stood on the dried up banks of the Des Moines River near Boone, Iowa, watching a train fly overhead on the Union Pacific’s famed Kate Shelley High Bridge. The train was traveling on a portion of the Overland Route, a highly trafficked rail route from Chicago to San Francisco. The massive structure the train crossed stands nearly 190 feet above the river valley, and is a half-mile long. While this certainly was a breathtaking scene for a 14-year-old bridge-hunter from Minnesota, it cannot compare to the story of the young woman for whom the bridge is named. Upon starting Civil Engineering School at Iowa State University in August of 2016, I began to understand the true impact this legendary heroine had on generations of Iowa residents.

A Railroad Family

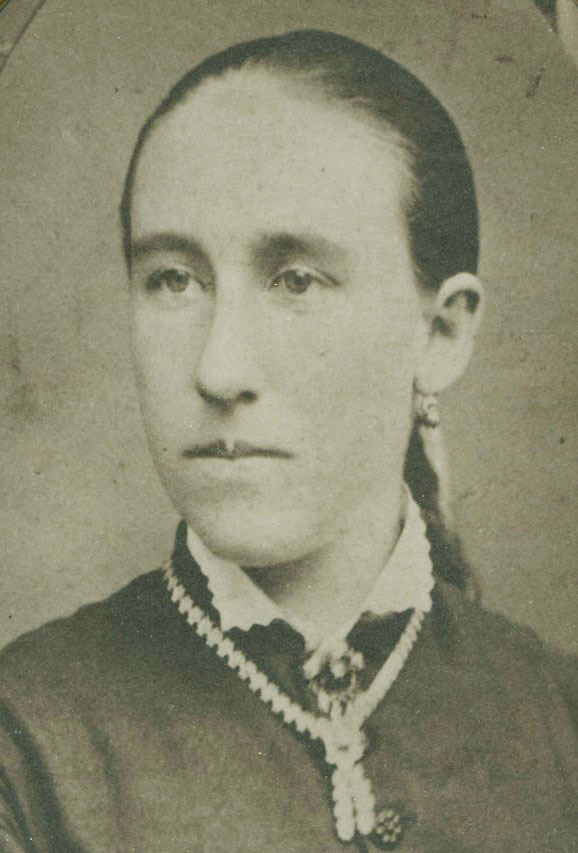

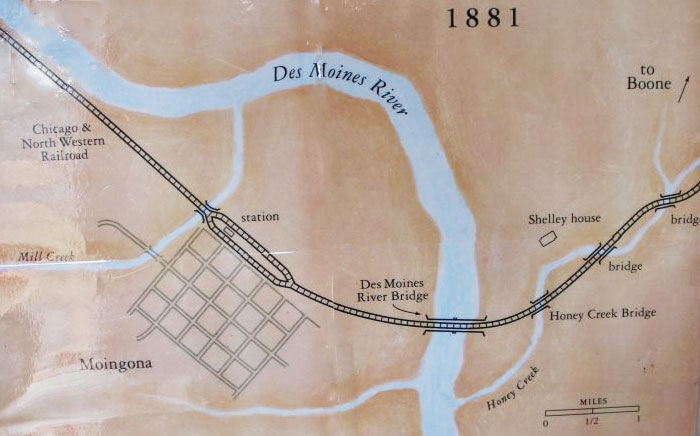

Katherine Carroll “Kate” Shelley was born in Ireland in December of 1863 to Michael and Margaret Shelley. With four additional children the family immigrated to the United States when Kate was one year old. At first, they lived near Freeport, Illinois, but later moved to Boone County, Iowa. The family settled on a large tract of land, which was unsuitable for farming, but the land was near the Chicago & North Western Railway mainline between Chicago and Council Bluffs, near Moingona. Michael took a job as a section foreman for the Chicago & North Western. Their land overlooked the Honey Creek Bridge.

When Kate was 12, sudden tragedy struck the family. Her father was killed in a railroad accident shortly after her brother drowned. Kate was suddenly thrust into control of the household, as her mother’s health declined.

The Beginning of a Legend

On the 6th of July in 1881, a particularly muggy and sunny day led to a series of heavy thunderstorms that came rolling out of the west in the evening. Honey Creek was already running very high from previous storms, and the heavy rains of this night would increase the swell. Kate and her mother kept a close eye on the stream, and at 11 PM heard a train with a four-man crew returning from Moingona to Boone.

The next thing they knew, tragedy struck. As Kate later recalled, there “…came the horrible crash and the fierce hissing of steam”. As the train attempted to cross the Honey Creek Bridge, the wooden trestle gave way and sent the engine, and its four-man crew plunging into the creek. Despite the initial shock of the accident, another thought came through the 17-year-old girl’s mind. Another train, The Midnight Express, would be coming eastbound in about an hour, and Kate decided it was time to race into action. Running to Honey Creek in an old dress and a tattered overcoat, she noticed two of the men clinging to branches. Ed Wood and Adam Agar had escaped the tragic accident with their lives, clinging to trees to prevent that from changing.

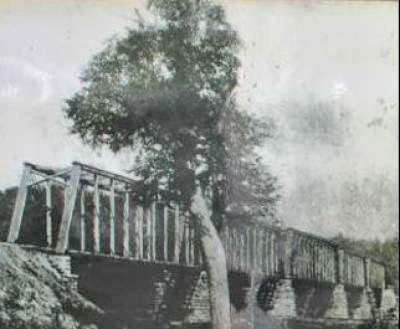

In the meantime, Kate knew she had to get to Moingona to stop the train. She left the men in the perilous safety to prevent another tragedy. The biggest obstacle was crossing the Des Moines River Bridge, a bridge that sat about 30 feet off the ground. However, to discourage trespassing, the railroad removed some of the boards. Kate would be in for quite a challenge as she crossed the bridge, literally on hands and knees. With lightning and wind still fiercely surrounding her, she fought off splinters and ripped clothing to make it to Moingona, before collapsing.

When Kate regained consciousness a short time later, she was told that the stationmaster had recognized her as the daughter of Michael and suddenly realized the express must be stopped. Kate insisted that a rescue party must be formed, and she returned with them to the Honey Creek Bridge. Ed Wood was tossed a rope and helped to safety, while Adam Agar was rescued once the waters receded. The other two crew members perished in the accident.

The news of the young heroine spread around Iowa, and eventually even made news internationally. Reporters from all corners of the United States traveled to Iowa to interview her. The ordeal, however, kept her bedridden for three months after the incident.

A World Waiting

When Kate regained her strength later that fall, the whole world was waiting. Passengers from the train she had saved pooled together a few hundred dollars for her. School children in Dubuque gave her a medal, and the State of Iowa contributed another. The railroad gave her a lifetime pass, among other supplies. A gold watch came from The Order of Railway Conductors. In addition, she instantly became a sensation with poems and songs written about her. Some were so impressed with her quick thinking, they raised enough money to send her to Simpson College in Indianola. Even the college president was raising money for her to come, being so enamored by her bravery. However, she came back home after one year, feeling that she belonged in Moingona.

As the years passed, her fame faded. She became a schoolteacher in Worth Township, making $35 a month. However, this money was not enough for ends to meet. In 1890, it was discovered that her home was mortgaged, and she was in danger of losing it. The public response for Shelley was nothing short of amazing. The mortgage was paid off by auction of a rug in Chicago, and she was granted a large sum of money by the State of Iowa. She was even written about for a grade school textbook.

Even in 2016, many children in Iowa learn about this figure from 135 years ago. However, her fame was far from over; and her biggest rewards were yet to come…

This is Part One of The Kate Shelley Story. Click here to read Part Two.

John Marvig – Photographs and text Copyright 2016

See more of John’s work at John Marvig’s Railroad Bridge Photography

I had always vaguely known about Kate Shelley’s heroism but never knew the full story. Thank you for a wonderful read and I very much look forward to the next installment!

The Des Moines River Bridge was built down in the valley. Trains ran down the valley side, over the bridge and up the other side. Pusher locomotives were necessary to help trains up the steep grade.

The locomotive that fell into Honey Creek was a pusher locomotive. It was checking the route for storm damage.

The construction of the high-level Boone Viaduct in 1901 offered a new, level route across the valley. This viaduct became known as the Kate Shelley High Bridge.

Thank you for this site! I always teach this story in my nonfiction section. The book does not have good photos of the bridge but with this site the children have a better idea of the wooden railroad bridge.

yah