A water tank’s chain rattles in the desert wind.

We’ve all noticed it. There’s something atmospheric about most railroad structures. There are so many examples. From major stations (and there would be much to say about the atmosphere of stations!) all the way through to the humble mile board’s increments of distance.

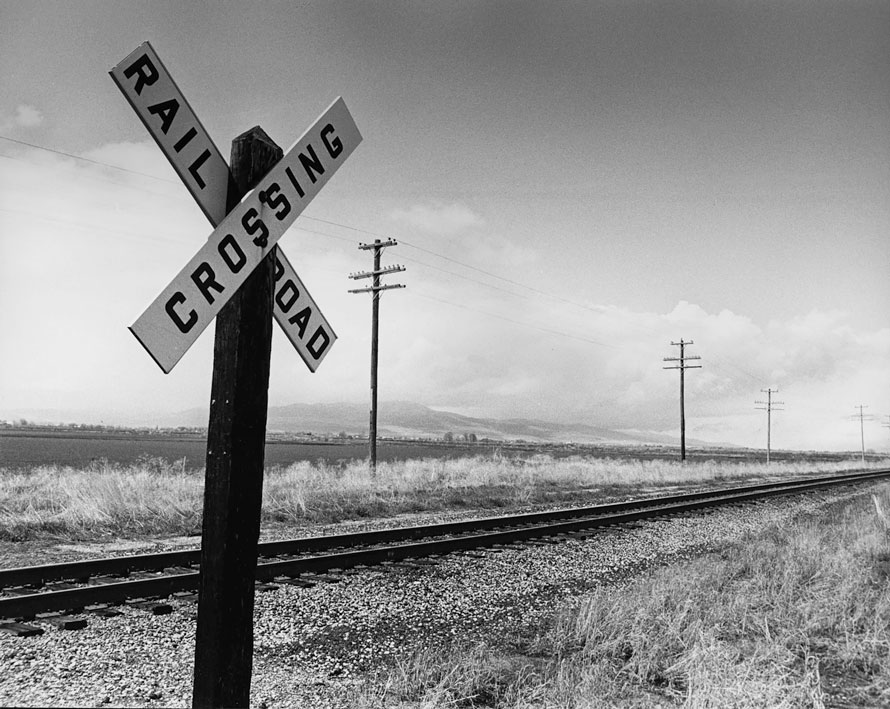

Then again there are these crossbucks at an isolated location not far from Promontory, Utah.

We drive up to the horizon which is a thin line of rails framed with inert sentinels. Here at its barest elements the railroad says to us that space and time can sometimes feel a little alien.

On the other hand if we want a less severe example of atmosphere (among many) how about the ephemerally yellowed windows of an interlocking tower at twilight?

Let’s think now about one thoroughly iconic railroad structure. Thousands of water tanks (or towers) were dotted around North America and they came in all shapes and sizes. Some were monumentally tall . . .

. . . and others were a little more improvised but most were an attractive marriage of form and function. The standout thing about all water tanks, however, is that every time you saw one it gave you a strong sense of place.

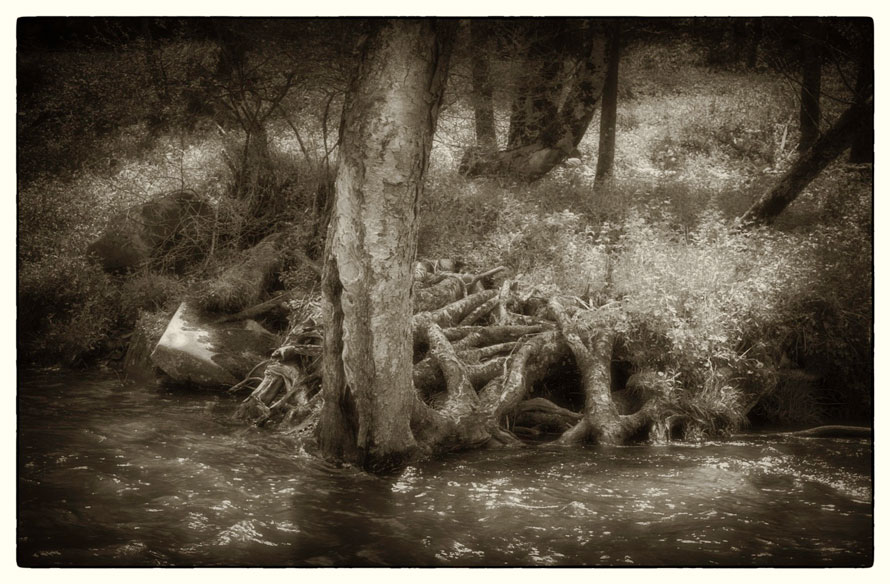

I came across a memorably rough-and-ready specimen while chasing a 1963 excursion on the Feather River Railway in Northern California. The FRR was a standard-gauge logging line that ran from the mill at Feather Falls to a connection with the Western Pacific at Bidwell Bar in the Feather River Canyon. Much of this railroad was inaccessible by car unless you were up for fording the odd rough stream, but about mid-day I caught up with this double-headed excursion train half-way to Bidwell at a leaking tank fed by a sluice from a nearby spring.

What stays in the memory is the silence, except for the sounds of dripping water, rattlesnakes and jointed rails creeping in the mid-morning heat. There was also the sweet smell of fir trees and a sense of anticipation. Just here it’s worth mentioning an experience once common to all backwoods railroads: the train can appear suddenly as if from nowhere! This is the muffling effect of trees and hills and the relative absence of grade crossings. Lastly there was the sound of volumes of water, the hiss of steam and the smell of hot oil on a summer’s day. You came away with a vivid sense of this particular place imprinted on your mind.

It meant the abiding value of day-to-day living referenced in the familiar buildings, landscape, routines, rules and rituals of the railroad.

Now I know that eccentric water tanks on bygone logging railroads weren’t scarce. But there remains one unusual fact about the Feather River Railway. Parts of its right-of-way now lie beneath an artificial lake created by the Oroville Dam, completed not long after these pictures were made. (A flood during this period increased the effect several fold.) Not only are the traces of rails, water tank, roadbed and spindly bridges largely gone but some of the surrounding lower hills, trees and streams will have disappeared too. I haven’t returned there but it’s a good guess that what was once a working railroad landscape has been altered almost beyond recognition.

We’re lucky then that an authentic reprise of taking water on a back-country railroad using geared steam locomotives can be experienced today. This takes place notably on the Cass Scenic Railroad historical operation in West Virginia where one of the Feather River’s Shays survives. A sense of place lives on at the Cass Scenic, even in preservation, and even without a train . . .

. . . though a locomotive will be along in a minute:

Indeed, so close is the continuity between the past and the present (and you could reverse the equation) that time on the Cass Scenic stands almost still. In the modern era this railroad continues to fit seamlessly into its natural environment:

And by the way, you might just spot another photographer!

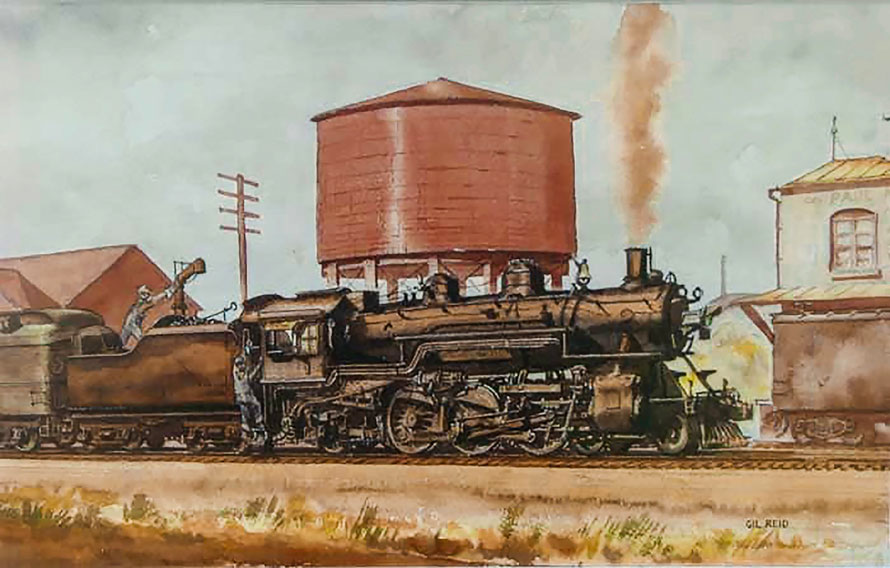

This brings us finally to Gil Reid’s watercolor artwork from 1943, “Noonday Water Stop,” originally published in Trains magazine and sold as a poster for decades in their back-page marketplace. It’s a deceptively modest picture of an indeterminate railroad. (Maybe it’s the Soo, Milwaukee, Chicago & Northwestern or Erie.) But there was an important reason for the longevity of this picture.

To Mr. Reid, a train stopping for water at a country station represented life as he would like to think of it on the home front during World War Two. (He was wounded at Anzio in 1944.) “There is an orderliness about the railroad,” he said.

A timetabled halt for water meant to Gil Reid a sense of well-being. It meant the abiding value of day-to-day living referenced in the familiar buildings, landscape, routines, rules and rituals of the railroad. If we were sitting solitary in one of his coaches you and I wouldn’t be able to take in the entire scene just as Reid painted it. But I think we would sense the ‘atmosphere’ of the occasion. And I’ll bet we would understand what it meant.

Call this ‘from another era’ if you must. But remember that other industries only have something they call ‘infrastructure.’

Robert Field – Photographs and text Copyright 2020

Learn more about the railroad art and career of Gil Reid at GilReid.com

Great photos, as usual. Great writing as well! Thanks.

Thanks Jim. I enjoyed doing it but what really matters is hitting the right note with someone else. So thanks again. Robert

My first time seeing your material Robert. Excellent story telling well-connected to superb photography. As I read, I’m feeling the light breeze, the scents in the air, and hearing crickets and wind through the grass. I’ll be back

Thanks so much Erik. These unique experiences on the railroad stick in the memory don’t they? Very pleased you liked the story. Robert.