Introduction

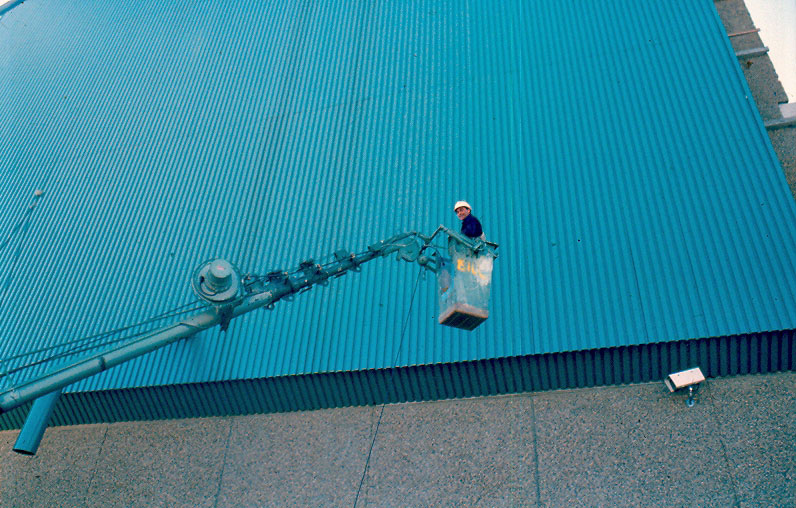

Jim F. Pearson photo

The concrete elevator seen here stands out as a unique example of Alberta’s ingenuity. For a time in the 1980s, it was the ‘Cadillac’ of the grain industry and the future of what was to come, replacing the iconic wooden grain elevators of old (and hopefully spread across Western Canada). The Buffalo-Sloped-Bin (BSB) 1000 series was the name of this futuristic design, created in collaboration between Alberta Wheat Pool (AWP) and Buffalo Engineering Ltd. Out of three examples built of this version, only two remain; one in Fort Saskatchewan and one in Magrath. The other elevator in Vegreville was demolished in 2009.

Background

From the early 1900s to the early 1980s, the wood grain elevator ruled the landscapes across western Canada. The late 1970s were good times for Alberta’s farmers and for one of the major western Canadian grain companies—Alberta Wheat Pool. A few years of bumper crops and high grain prices kept the wooden elevator network humming and added well to the profits of the Pool. With some of the surplus profit, AWP decided to do some design work with an engineer from Edmonton, by the name of Klaus “Nick” Drieger. Drieger and his company, Buffalo Engineering Ltd., drew up the initial concepts of the new concrete grain elevator to be built with large modular precast concrete pieces, sloped grain bins (to help with the grain flow) and clad with non-combustible pre-finished metal panels.

Using pre-cast structural components would help the problem of maintaining a large workforce and help reduce costs in building these grain elevators in remote locations. The modular design would allow for easy increases in capacity by adding additional modules of about 55,000 bushels each, giving the BSB the flexibility to be built to virtually any size. Concrete would also help in reducing over-pressure on the elevator walls during filling and emptying. These pressures are often difficult to determine and costly to design for (and to fix if a hole blows out the side of an elevator). The dual vertical elevating ‘legs’ would include a double row of cups on each belt and the other pieces of equipment were designed to have a capacity of 5,000 bushels per hour (bph)! Five unloading spouts on the track side were also added to speed up the loading of grain cars. The latest and best automation and dust control systems would be implemented as well, including positive air pressure in the office area to maintain a dust-free environment while negative air pressure in the grain handling equipment area would keep the dust in these zones. With previous elevator designs, the elevator agents pre-weighed the grain into separate bins to be loaded into the railcars via the vertical elevating leg (to save time). The BSB elevators utilized an over-the-track bin system that filled with the grain (in layers) prior to being prepared for shipping. Once the appropriate bins were filled, it was directly unloaded into the railway cars below.

Jim F. Pearson photo

With these factors in mind, the AWP was convinced that this was the design of the future, and formed a partnership with Buffalo Engineering The result was Agritec Engineering Systems, which was owned 50% by both companies. Agritec would design, market, and build the BSB ystems. Alberta Wheat Pool analyzed its existing grain elevator network and decided that Magrath would be the location for the first Buffalo terminal. Agritec commenced construction in late January, 1979, while AWP authorized additional BSB 1000 series elevators at Fort Saskatchewan and Vegreville. On June 4th, 1980, the Magrath Buffalo officially opened to the general public. Over 2000 attendees toured the elevator on the first day. On the second day, grain industry officials from Kansas, Chicago, Minneapolis, Winnipeg, Regina, and Edmonton were given a detailed tour and review of the complex. Things were looking up! In 1980 Alberta Beton Limited and Buffalo Beton Limited were formed to assist with the development of these elevators. Alberta Beton would build the elevators, and Buffalo Beton would market the elevators to other grain companies in western Canada. In 1982 the Vegreville BSB elevator was opened for business.

However, not all was rosy. Issues with the construction processes on the 1000 series elevators caused delays on-site. The thirty-degree sloped bins worked well, except for certain grains (barley and oats) which would stick to the rough surface of the concrete, causing plug ups and forcing employees to go inside the bins to get the grain moving. Using all precast components did speed up construction, but it allowed for pockets or oddly shaped corners in the bins which affected the grain storage. The precast panels sometimes didn’t fit flush so gaps would form and then the grain would leak out. (They were plugged up with tubes and tubes of caulking.)

Another setback was the configuration of the new advanced equipment (jumping from conventional elevators to the new style) which utilized horizontal conveyors to move grain between the bins. Typically, in conventional wooden elevators, loading of railcars was done by gravity, while the vertical elevating ‘legs’ were able to move grain between the bins. With the new BSB elevators, both the elevating legs and the horizontal conveyors (two trackside conveyors and a central third conveyor that took the grain to the front of the elevator) had to be in operation at the same time. Also, the complicated gate system at the upper and lower ends of the concrete bins was confusing to operate and had issues with the gates not closing properly and allowing the grain to leak out. All the parties involved knew that it was a new concept and there would be bugs in the system, but if AWP was going to take this concept to more locations, improvements would be needed to fine-tune the design. With Canada entering an economic recession, orders for new BSB elevators slowed and after the Vegreville location was built, the future looked grim.

ABL Engineering Ltd. (re-organized Agritec Engineering) went back to the drawing board and the 2000 series was born. Out of these series three were built at Lyalta in 1981, Foremost in 1983, and Boyle in 1986. But let’s look back a bit more in detail at the BSB 1000 series elevator.

The Magrath BSB 1000

View of the BSB 1000 and the adjacent Alberta Wheat Pool elevator taken in the summer of 1981. Note the P&H grain elevator in the background

Galt Museum & Archives photo P19991805452

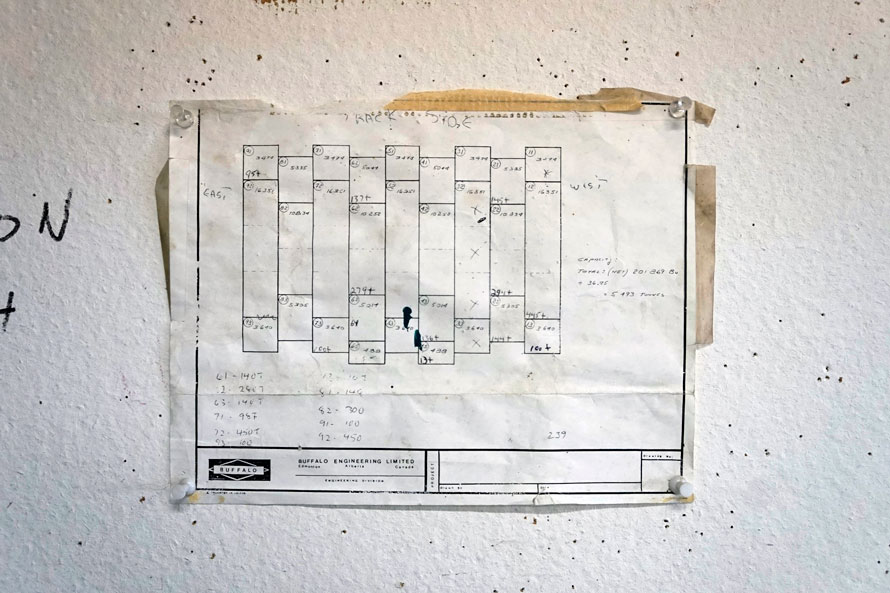

Agritec commenced on the first design of the Buffalo Sloped Bins, the 1000 series. It would be comprised of 42 square pre-cast concrete modules (stacked like cordwood) at a thirty-degree angle from the ground and could hold approximately 206,000 bushels. Each bin within these modules ranged from 3,700 to 5,400 bushels in size. As the grain flowed into the bins in layers of 6 to 8 inches, the bins filled up at the same depth and are maintained over the full length of the bin. From the ground level, the elevator is approximately 120 feet high, or the height of a ten-storey building. The roof slopes to a height of six stories on the track side. At that point, the BSB elevator would include five spouts to load up to five rail cars at a time, unlike the traditional wooden elevator which can only load one rail car at a time. The spouts were semi-enclosed in a metal awning to protect the loading process and were able to divert moisture from the roof.

As mentioned previously, the issues with building these grain elevators and the growing pains of the new, advanced conveyor and dust equipment caused considerable headaches to Agritec and to the elevator agents of the AWP.

The Magrath example served Alberta Wheat Pool well, and later on, under the Agricore banner. In the mid-1990s, the AWP construction crew performed a major upgrade of the Magrath Buffalo elevator, and the middle portion of the roof was ‘bumped-out’ to accommodate new enclosed distributors, new dust-handling equipment, and upgraded horizontal conveyors (based on the improvements of the BSB 2000 series). Included with the upgrade was additional piping to load the railway cars directly from the vertical leg (with increases in capacity to 8,000 bph), and a new automated scale. These upgrades not only kept AWP competitive but reduced capital costs in the lean years, and kept the valuable construction staff employed. However, it was one of the several hundred elevators that would be sold off when Agricore merged with United Grain Growers in 2001. It was then sold to competitor Parrish & Heimbecker, a smaller player in the Canadian grain industry who had already owned a couple of wooden grain elevators in Magrath. P&H owned the Buffalo for a few years before selling it off, along with a couple of the original wooden elevators, to a local farming company; Ben & Donna Walters, who operate them currently.

Jason Paul Sailer photo

Touring the Buffalo

Jason Paul Sailer photo

Fast forward to January 2017. After visiting the Foremost Buffalo 2000 example in October 2016, my appetite was whetted and I look forward to going after another local Buffalo example, the Magrath elevator, which I had driven by many times before on the way to and from Waterton Lakes National Park. I often wondered what the heck was that elevator about? After some initial research and ‘old-fashioned elbow grease,’ I was able to contact the current owners of the elevator who still uses the facility and who graciously allowed us access. I invited a close friend, Chris Doering, who also enjoyed photographing elevators, to accompany us on the tour. On a cool weekday afternoon, we arrived at Magrath and with the company’s elevator agent Richard Kirk unlocking the door, we began our tour!

From the outside, it looks very similar to when it first opened in 1979, except for the absent railway tracks, a bump-out on the roof, a faded Parrish & Heimbecker shield logo on the north front facade and the town’s name sign below that. It is interesting to see a grain elevator that is painted in the blue/green colours of the AWP with a P&H logo painted on it!

Jason Paul Sailer photo

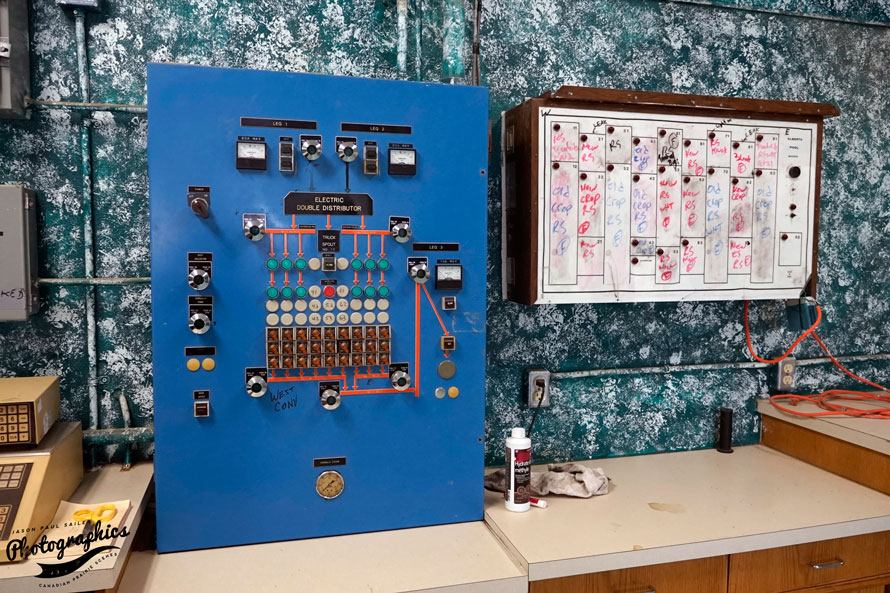

Walking inside the office, the first thing we noticed was the modular layout of the concrete beams & columns, which was the basis of the Buffalo design. With Richard explaining the operation of the instrument panel, we suddenly pause to hear trickling grain behind us! We all turn around and watch in amazement a steady trickle of grain seeping out of a small crack in the ceiling above until it slowed down and then stopped. Richard walked over and quickly swept the loose grain up, and smirked at our surprised looks on my and Chris’ faces. A normal occurrence he says and then takes us through a side door to go downstairs.

Jason Paul Sailer photo

I pause at top of the stairs and look down to see a 50-pound man-lift weight used as a doorstop! Interestingly enough it is stamped with ‘Alberta Wheat Pool Elevator A’. Walking through the door I had to take a step back as I was looking into the belly of the Buffalo, where a maze of galvanized metal pipes, conveyor belts, massive concrete columns, hydraulic rams, and green painted gates that controlled the flow of grain was located. As Richard was explaining the process to Chris, I walked slowly around taking it all in. We were adjacent to where the trackside operations would have occurred originally. Richard mentioned they use the trackside loading spouts to load semi-trucks when the demand warrants. He pointed out the gap-filling techniques that Alberta Wheat Pool, P&H, and themselves undertook to reduce grain loss that had resulted from the original design flaws the precast panels presented. He gestured to the pipes overhead and explained how grain was released from the rear of the bins down a chute to two horizontal conveyors that would transfer the grain to a central conveyor belt that directed the grain to a scale at the front of the elevator and then to the rear loading spouts just to the outside of our location. The conveyor system worked well but required a fair bit of maintenance, something AWP would soon learn in the early years of running the Buffalo elevators.

Jason Paul Sailer photo

We then went back up the stairs to the main level, and up a separate set of stairs to the upstairs levels. Through the first door, we entered a rectangular room where the scale was located. Along one wall, there were several green painted metal bin access doors, and in one corner were some boxes, and a red man-lift standing there! Richard mentioned the man-lift came from one of the wooden grain elevators that had stood nearby the concrete Buffalo. Leaving the room and going up another set of stairs we enter another room that was directly above the driveway space, and through an opening in the slab, we could see the driveway below. Directly to our right is the double vertical lifting legs that would take grain from the driveway level upwards to the top of the Buffalo (where it would get distributed to the proper bins). The floor level is lighted with clear Plexiglas panels which rattle slightly with the wind outside, and with the sloped concrete grain bins above our heads, it was a bit intimidating!

Jason Paul Sailer photo

At the door, we could of went up another long flight of stairs to the top level of the Buffalo, where the dust collection equipment and the distributors were located, but Richard had to go to one of the neighboring grain elevators to get the driveway ready for an incoming semi truckload, so we decided to head back downstairs.

Chris and I looked through the office a bit more (noting the former Buffalo Engineering bin diagrams pinned to the bulletin board) and then proceeded down a dusty hallway past empty offices to another reception area that was currently being used as storage. From what he told us it was used by the neighboring Richardson grain company for a bit while they were renovating the offices at their facility. Through the side door, we enter the driveway that was framed out with precast panels (with their embedded lifting rings) and the massive concrete columns. After a few minutes of exploring we went outside while Richard headed over to the former P&H grain elevator to meet the semi-truck.

Jason Paul Sailer photo

Jason Paul Sailer photo

Rounding the corner of the concrete elevator we can see the five loading spouts where the metal grain hopper cars (or boxcars) would have been loaded. Potentially up to five cars could have been loaded at a time, averaging thirty minutes per car to load. Not bad for a 1980s design, but slow considering the present-day high-output grain elevators average loading time of seven minutes per car! Additionally, the rail car siding capacity at these elevators came into play as well. Several of the BSB terminals were located on branch lines that had smaller siding capacity (usually twenty-five cars or less—most times twelve cars), unlike the newer high-output elevators that have fifty or more car capacity on their sidings.

Jason Paul Sailer photo

Currently, the newer elevators include a ‘loop track’ which enables the railways to bring the cars onto the property and leave the engine & cars for an separate crew to operate them on the elevator property. Then the elevator would load the cars and then call the railway back to pick them up when they were done. These types of tracks could easily hold an entire train (up to 135 cars) without the need to break them up into smaller units! With the smaller siding capacity came the issue of moving the loaded cars as well to keep the process going at a good rate. The older methods of a winch system did work but weren’t as fast as a car mover or a dedicated locomotive moving the cars along.

Jason Paul Sailer photo

Jason Paul Sailer photo

Overhead we can see the more recent upgrade of a gantry where employees would tie safety lines as they walked along the grain hopper cars’ walkways during the loading process. Looking towards the southeast we see the P&H grain elevator (a former Ellison Mills) where Richard’s truck is parked outside.

Jason Paul Sailer photo

The oldest elevator in Magrath still standing dates back to 1917. It’s painted in Parrish and Heimbecker colours, the firm’s logo still displayed on its sides. Originally built for the Ellison Milling Company, it was acquired by the P&H company when that firm took over all of Ellison’s operations in 1975. In approximately 1972 Ellison added the round metal “annex” bins, as a way to increase capacity and upgraded the elevator legs. The wood one on the opposite side, is much older, dating to the late 1930s. Looking towards the southwest we see a vertical concrete grain elevator, built in the 1970s, owned by the local Church of Latter-Day Saints, and directly west of the Buffalo was a former Alberta Pacific/Federal/Alberta Wheat Pool elevator that dates back to 1937.

By 1903, Magrath was a significant grain delivery point for the area with a single elevator and flour mill in operation. By 1911, it had increased to four-grain elevators with a combined capacity of 116,000 bushels. By 1920 there were six elevators, though a single elevator would be lost sometime afterwards and the remaining elevators would remain as status quo well in the late 1980s. In its day two long elevator tracks on either side of the mainline were needed to service these elevators, plus the associated industries including fertilizer sales, twine, chemical, coal, etc. The Ellison/P&H, the concrete Buffalo, and the Alberta Pacific/Federal/AWP elevators are all owned by B&D Walters Farms, so Richard is busy doing work at any one of them at any given time!

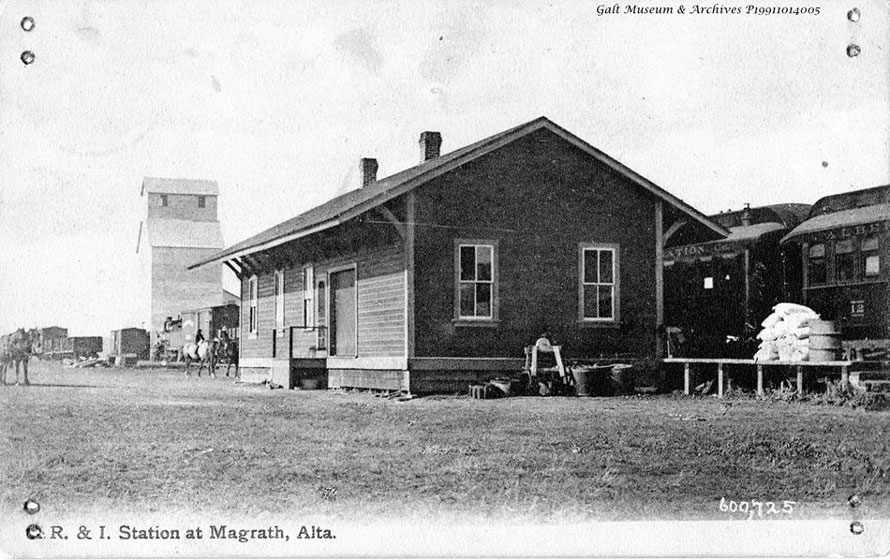

Alberta Railway and Irrigation Company train station at Magrath, 1909.

Courtesy Galt Museum & Archives P19911014005

The Cardston CPR Subdivision

In 1900, as irrigation was developing in southwestern Alberta, the Galt family of Lethbridge commenced another railway project under the name of the St. Mary’s River Railway Company (SMRRC). The railway was narrow gauge and extend from Stirling west to the intake of the St. Mary’s canal at Spring Coulee. Recently emigrated Mormon settlers from Utah were employed by the Galts to build both the railway and irrigation canals. The railway used the equipment of the parent Alberta Railway & Coal Company (AR&CC) and later Alberta Railway & Irrigation Company (AR&IC). Between Raymond and Magrath, the railway line crossed Pothole creek on a low-level wooden bridge, and two other railway trestles had to be built between Magrath and Cardston. By 1902, the railway had reached Cardston and narrow gauge trains were in operation. In addition, a branch line was built from Raley (the station before crossing the St. Mary’s River by Cardston) southwest towards the settlement of Kimball. It split halfway between the two points and turned slightly east and stopped at Woolford. In 1907, work began on upgrading the narrow-gauge line to standard gauge and work was completed by the end of the year.

In the spring of 1912, the Galts began negotiations with CPR to take over the remaining railway network, including the line to Cardston. By June, a deal was in place and the CPR took over ownership and the former Galt network was placed under the CPR Medicine Hat division. The former SMRCC track was renamed the CPR Cardston subdivision, and the track from Raley south was renamed the CPR Woolford subdivision.

In 1927, CPR extended the railway line west from Cardston through the Blood Indian reserve to Hillspring and Glenwood in order to serve the needs of the newly created United Irrigation District. In 1929 the former railway line from Raley to Woolford was re-instated and later extended southeast towards the International Border, ending at a point called Fareham, later Whiskey Gap.

Passenger train service varied in the early years of the CPR takeover; starting with daily (except Sunday) service between Lethbridge and Cardston, and cutting back to three days a week in the early 1930s and later transitioned to mixed train service by 1933. In 1948, gas-electric car service ‘doodlebugs’ were put into place running daily (except Sunday) from Lethbridge to Glenwood. However, not enough passengers meant the route to Glenwood was cancelled in 1950, and the mixed train option ended in 1955.

By the mid-1970s, CPR began re-analyzing its rail network and began selecting the lower mileage / non-productive branch lines to be abandoned. As per the Federal government regulations at the time, the appointed Hall Commission reviewed all the applications including portions of the Cardston subdivision. At the time, trains operated on a mixture of 80 and 85-pound steel rails, and the main grain delivery points included Welling, Spring Coulee, Magrath, Cardston, Hillspring, and Glenwood. AWP operated at all those points, United Grain Growers at Cardston and Hillspring, and P&H at Cardston only. For a period of ten years (1964 – 1974) approx. 3,000,000 bushels of grain was hauled from the region by CPR trains. Nevertheless, the Hall Commission recommended the track from Cardston to Glenwood be abandoned by 1980.

As the years pass the line suffered from deferred maintenance and service became unreliable at best. CPR became disenchanted with the money-losing branch lines and did everything in their powers to rid themselves of them—only government regulations kept this from happening faster. In the spring of 2000, service ended between Cardston and Magrath, and the track between the two centers was removed. In 2001, service to Magrath was severed when a flash flood washed out several culverts supporting the track across Pothole Creek, just east of the town. CPR had installed the culverts just a few years prior when it retired its wooden trestle. At the time, CPR didn’t operate many trains down to Magrath. By 2002, train traffic on the former Cardston subdivision was reduced from Stirling to Raymond only. CPR removed the track between Magrath and Raymond, and a large portion of it was donated to the Great Canadian Plains Railway Society, for the development of the Galt Historic Railway Park at the junction of the CPR Cardston & Coutts (later Montana) subdivisions just outside of Stirling. The portion from Raymond to Stirling was placed on the abandonment list in August 2005 and continues to be on the list, with no real future left.

Nick Korchinski Collection

Great Canadian Plains Railway Society / Galt Historic Railway Park

Endangered Species

The grain companies (Alberta Wheat Pool included) suffered from the economic recession in the mid 1980s as well as the few years of bad harvests, due to poor weather—drought one year and damp another. This hurt the company coffers and bottom line as the elevator agents would have to spend more time drying the damp grain and not shipping it out. Rising inflation hurt the construction of newer high-output elevators (like the BSB elevators), as the older wooden elevators were having trouble keeping up with the new changes in the transportation. It was harder to load grain hopper cars on sidings that were made for grain boxcars, and several elevators couldn’t manage that well. With a fluctuating economy and dwindling profit, it was decided that the pricier BSB elevators would have to be put on hold for the meantime until things improved. As mentioned previously, only three of the BSB 2000 series elevators were built. It was decided to upgrade and renovate some of the older, larger elevators and to build a few wood cribbed double composite ‘high-output’ grain elevators in the meantime until things improved. Some of the upgrades for the wooden grain elevators included new semi-truck capable driveways and scales, increased mechanization and drying equipment inside the elevators, additional steel grain bins added on the exterior, and where if possible the addition of increased railcar capacity up to twelve cars per track, with some places up to twenty-five car capacity. With the renovated grain elevators and the few new wood cribbed elevators built, the Alberta Wheat Pool was able to get by through this period.

While this was going on, in the background the AWP began analyzing their current elevator network and picked some of the older, smaller capacity elevators to be closed. To keep the costs down, it was the best thing to do, especially with the added talk from the Federal Government on keeping the railway branch lines operating until the year 2000. There was lots of uncertainty by the grain companies on this announcement—what would happen to the elevators after that date and if the railway ceases operation on these branch lines? The grain companies would be stuck with elevators and no way of getting grain to and from them. On the other end of the spectrum, the railways were reluctant to invest in some of the ageing prairie branch-line networks. The railways were also dealing with shortages of both locomotives & grain cars, and reduced revenue due to the Crowsnest Pass Act Agreement (aka the ‘Crow Rate’). The Crow Rate would be replaced by the Western Grain Transportation Act in 1984. Who was to blame for this situation? The grain companies? The railways? The farmers? Why would the railways invest in these money-losing lines when the grain companies don’t invest in repairs or new grain facilities along these lines? If the railways don’t come to move the grain then the farmer’s grain can’t be moved and he can’t make any money, money that would go back into repairs and new grain terminals.

Given the extensive nature of the prairie branch-lines (a result of intensive competition between CN and CPR and their predecessor companies to get the most $$ from the Federal Government at the turn of the century to build them), several branch-lines became candidates for abandonment as there wasn’t enough business to keep them going. Subsidiaries from the Federal Government to the railways did help in the short term in operating these money-losing lines, though any money from that rarely or never went to the maintenance of the track—this would lead to more drastic measures later on. In 1974, the Federal Government announced a basic prairie branch-line network of 12,414 miles (19,978 km) that would be kept safe to the year 2000. An additional 6,322 miles (10,174 km) would be analyzed by the Hall Commission to either be saved or abandoned. The Hall Commission later determined that out of that number, 2,165 miles (3,483 km) would be abandoned and the remainder would be transferred to another Government agency, the Prairie Rail Authority (PRA). The PRA would have the authority to gradually dispose of these lines over a twenty-five-year period. However, the Federal Government disagreed with the Hall Commission’s report and decided that an additional 1,498 miles (2,411 km) originally slotted to the PRA would be abandoned instead.

With the older grain boxcars wearing out, a new method of transportation was needed to improve efficiency and profitability for everyone involved. The boxcars were labour-intensive and time consuming to load & unload, so hopper cars were eyed up as their replacements. The Federal Government assisted in the funding of approx 12,400 steel and 2,000 aluminum grain hopper cars to be divided equally between CN and CP, with railways looking after the maintenance. Nicknamed “Trudeau Hoppers” (after the Liberal government at the time) these new cars were a welcome sight for both the railways and the grain companies. The remaining grain boxcars weren’t ignored, as they received funding from the Federal Government for repairs as well. Now with the oncoming influx of new hopper cars, the ageing railway tracks weren’t able to accommodate these new cars! Again, the Federal Government was pressed to help update the railway branch-lines to allow the railways to get the grain moving, and referring to the track picked by the Hall Commission, a plan was put into place. Where the track was upgraded, those lines would get hopper cars and the ones who didn’t get updated would use the rehabilitated grain boxcars. However, by the late 1990s / early 2000s some of these rehabilitated branch-lines would be abandoned by the railways (for either cost or dwindling business) and some would get re-sold to local area farmers to start short line railway operations, and some cases the tracks and material was removed and sent to another branch-line to be reused.

By the early 1990s, the first of the slip-form concrete high-output terminals were being built, with increased railcar capacity that allowed for bigger trains to be unloaded and loaded in more efficient ways. As mentioned previously, the Buffalos could load grain relatively faster into boxcars and grain hoppers compared to the traditional wood grain elevators, but they couldn’t match the present-day high-output terminals in loading times. The slip-form concrete elevators utilized a quick-setting concrete to be poured continuously in a moving form, allowing for cast-in-place (no joints or seams). Inside and outside forms create the cavity of the walls, and inside the cavity, reinforcing steel is tied together vertically & horizontally to reinforce. The form is then connected to jack rods with hydraulic jacks which move the form vertically in minute increments as the concrete is being poured. The rate of “jacking” is in direct relation to the rate at which the concrete cures sufficiently to advance the forms. Typically, the forms are raised 20 – 24 feet per 24 hours. Once pouring begins, it continues around the clock until the top of the structure is reached, allowing for a monolithic poured concrete structure. Actually, the method of slip-forming has been around since the early 1900s, with many grain terminals at the Ports that were built with the same concept. It fell out of favour for a while but gained resurgence in the mid to late 1980s. Alberta Wheat Pool’s first slip-form elevator would be located at Grande Prairie, AB in 1989.

Always Look Back

Out of the original six BSB elevators in Alberta only four remain; the Vegreville & Boyle examples were demolished in 2009 and 2010 respectively.

The BSB 3000 was a proposal for a west coast grain terminal, to be located at Prince George, British Columbia, in the early 1980s. Buffalo Beton made several presentations to the grain terminal consortium at the time (consisting of 34% AWP, 30% Saskatchewan Pool, 15% United Grain Growers, 9% Pioneer Grain, 9% Cargill Grain, and 3% Manitoba Pool ownership of the shares). On a side note, the terminal was 50% funded by the Alberta Government and 50% by the stakeholders in the consortium. The push behind the construction of a new grain terminal in Rupert, however, was more than a consequence of this change in market conditions. The Alberta economy in the 1970s had been fueled by rising oil revenues and commodity prices. Flush with cash and with a Heritage Trust Fund started in 1976, Alberta sought to invest in projects of relevance to the provincial economy. Since grain exports were hindered by the lack of developed infrastructure, it was the provincial government of Alberta that pushed for and helped finance the construction of the new grain terminal in Prince Rupert. The provincial government of Alberta assumed the dominant leadership role in 1979 and threatened to pursue other options if the grain companies did not back the Rupert port. Supported by Alberta money, up to 80% of the costs of the eventual $277 million investment were guaranteed by the province, the grain terminal went ahead (with a conventional design instead of the BSB 3000 in the end) and was completed in 1984.

Ironically the Buffalo design survives in Brazil, where Buffalo Beton Limited was able to secure contracts with the Brazillian government to build five terminals in 1982. These elevators were designated BSB 4000 series, building on the successes of the BSB 2000 series. four elevators at a capacity of 600,000 bushels and the final elevator at a whooping 3,750,000 bushels. Although the Alberta Wheat Pool was not involved in the financing or construction arrangements, they received royalty payments for the transfer of the technology, which assisted the financial aspects considering the economic recession at the time. The Brazilian BSB terminals would be fully operational by mid-1985. Buffalo Beton continued to drum the BSB system internationally and at one point had up to twenty countries (including the USSR, Egypt, and China) signed up, but for reasons unknown, their respective deals didn’t go any farther than paper contracts.

Jason Paul Sailer – Photographs and text Copyright 2020

Acknowledgements Hope & Richard at B&D Walter’s Farms – THANK YOU! Alberta Historic Resources Foundation (Judy Larmour) https://albertashistoricplaces.wordpress.com/2014/07/31/a-futuristic-elevator-that-lives-on-in-brazil/ Chris & Connie aka BIGDoer.com http://www.bigdoer.com/6084/exploring-history/buffalo-2000-grain-elevator-lyalta-alberta/ http://www.bigdoer.com/25048/exploring-history/buffalo-2000/ https://www.bigdoer.com/29112/exploring-history/grain-elevators-of-magrath/ Steve Boyko http://blog.traingeek.ca/2015/03/buffalo-grain-elevators.html http://blog.traingeek.ca/2016/03/the-branchline-rehabilitation-program.html Eric Gagnon http://tracksidetreasure.blogspot.ca/2009/01/cp-grain-boxcars.html http://tracksidetreasure.blogspot.ca/2010/04/canadas-cylindrical-grain-cars.html Alberta Wheat Pool collection, Glenbow Museum Jim A. Pearson (Vanishing Sentinels) Jim F. Pearson (retired AWP engineer)

Years ago when I was officiating at the Canada Summer Games in Saskatchewan (Saskatoon I think), we had a tour of one of the new elevators. It seemed to be quite efficient. Sad to hear that they are now being torn down. Not sure of the year, but it was probably in the 1980’s.

Great article, Jason! It’s great to see the inside of the elevator through your lens!

Thanks Steve! Photographing it in 2014 with you helped to spur my interest in these type of elevators.