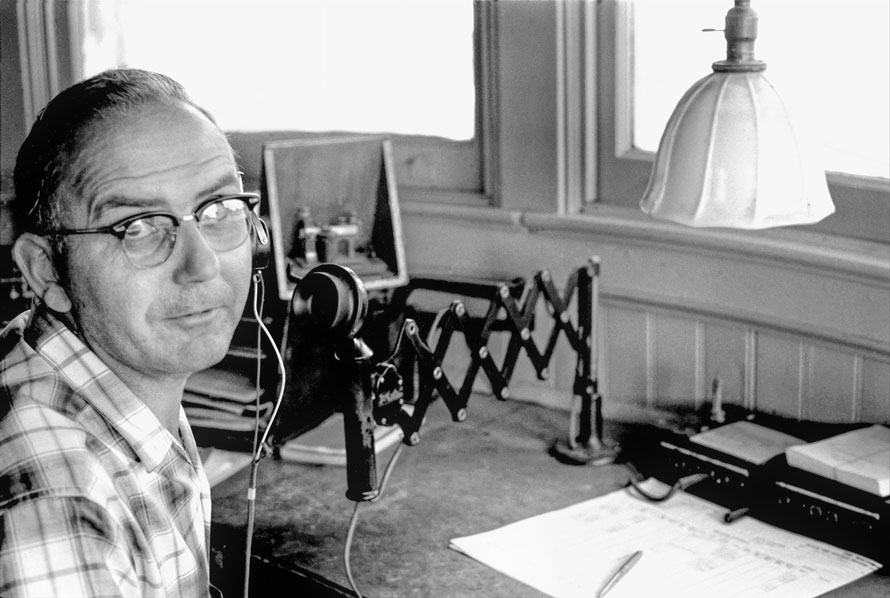

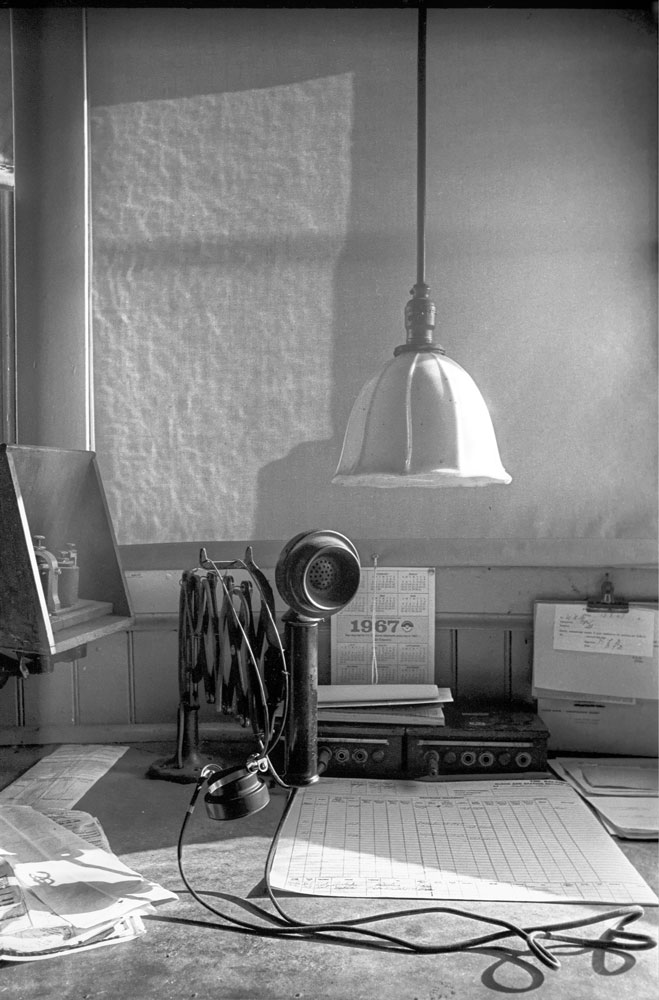

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad station in Madeira, Ohio, was a great place to be in 1967. It had five active telegraph wires. One was for Division use among operators and the dispatcher in Chillicothe, Ohio. A few operators and the DS were old ‘lightning slingers’ so the wire did get some use. Two more were long distance company lines.

The last one was Western Union. Yes, telegrams were still sent and received. Every day at 11:59:30, wire traffic would stop for the national time signal at EXACTLY noon. It ticked down the seconds until a brief pause, then noon. Thereby all clocks everywhere on the system were synchronized.

Of course a Seth Thomas clock sat on the wall, quietly ticking. I got to wind it every now and then.

There was the phone line among operators and the dispatcher. Every train that passed was dutifully OS’ed to the station behind, the station ahead and the DS.

Madeira sat at the top of the ruling eastbound grade out of Cincinnati. The grade leveled out a few feet past the station, then descended more gently.

About thirty-some miles away, past Loveland, stood the station in Midland City. The B&O branched there. One line went north through Washington Court House while the other went east to Chillicothe. There was a small CTC panel controlling a few miles of line. The agent, George Wills, was a grouchy old guy close to retirement.

There was nothing to do but wait and hope and pray. The clock ticks sounded like gunshots in the heavy silence.

At this particular time in December, track work was being done. All of the signals were down, so the entire line between Midland City and Madeira was run as manual block. 19 or 31 orders were hooped up to every train at each end.

Another railfan, Rick Little, and I were at the station late one early winter afternoon. The call bell rang out most urgently. It was George Wills. He hooped 19 orders and the Clearance Card Form A to three light diesel units passing through. But! He forgot to attach a message. It said to watch for the local crew who would be taking the siding at Loveland. George was frantically calling to see if anyone could stop the light engines. Couldn’t be done: no roads, no company facilities, no way to contact the crew.

There was nothing to do but wait and hope and pray. The clock ticks sounded like gunshots in the heavy silence.

The railroad phone rang. It was Loveland Tower: WRECK!

Rick and I jumped into my car, and we made for the site. We knew how to get there. It was getting dark, would there be enough light for photos?

FOUND IT! As we drove closer, a very large, gruff, Railroad Bull came our way. “You guys get the hell outta . . . oh, it’s you.” It was Mr. Priddy, who knew us well. He told us to get in and shoot fast because the Super was on his way. Mr. Priddy would give us a shout when he arrived.

It didn’t look so bad at the head end.

We drove to the hind end.

It was bad.

The rear-end crew had been on the ground while taking the siding. Miraculously, no casualties! But the caboose was hit so hard it literally flew almost completely into the gondola car in front of it. The front of the lead light unit didn’t look so hot, either.

I got a couple of shots when we heard Mr. Priddy shout and saw him waving his arms. Time to go, quickly.

Because of the accident, all traffic was stopped. I managed one last shot in the fast fading light.

So, what happened? The crew should have paid closer attention to the Clearance Card. They should have stopped and backed up when the message was missing. But they didn’t. It should have been OK-ish, because with signals out, the light units should not have been traveling faster than 15 mph.

The engineer had the light units running at 45 mph when he came around a curve with obstructed vision. He saw the local and made an emergency set on the brakes, but it too late. They plowed into the caboose.

There was fallout. George Wills was fired and lost his pension not long before his scheduled retirement. The engine crew was furloughed for several years before they were called back.

These are the only photos. And it took only forty-five years for them to surface.

William R. Jolitz – Photographs and text Copyright 2020

I’m glad nobody was hurt! Good thing you were there to capture the incident… and share it, finally!

Interesting article on MBS (Manual Block System). I was familiar with this type of operation on PC’s former Springfield Div (ex-Boston and Albany RR). We had double track mainline CP 187 (Post Road)-CP 4 (Beacon Park , Boston), with a few TCS (old NYC Traffic Control System) portions of a mostly ABS (Automatic Block Signals), timetable direction (TK 2 east/TK 1 west).

Also to facilitate movement on mainline, hand thrown cross over switches were at various points between CP 187-CP 99 (Niverville, Chatham, East Chatham (automatic interlocking with spring switches), CP 150-CP 148 (Pittsfield), Hinsdale, Washington, Chester, Russell, Westfield and Trap Rock.

It was at these locations that the West End Disp could establish “temporary” Manual Block Stations in charge of an operator, to cross over trains to run “against the current of traffic” (i.e., BA-4 operate TK 1 CP 148-Hinsdale, and crossover TK1 to TK 2 and operate normal on TK 2).

This is what we called “railroading” back in the day.

I should “clear” up my comments further. When we operated with Operators in charge of hand thrown crossovers (in PC/CR days), it was for a variety of operational reasons, derailments on either of the mainlines between CP 187-CP 44 (Worcester was start of TCS on TK1-TK 2), scheduled track work that would take one track out of service between points on RR where you could cross a train/engine from one track to another, stalled train on the mountain (between, say Chester and Pittsfield), train with mechanical issue (drawbar and/or knuckle train separation).

Sometimes, when the Dispatcher couldn’t establish a Block Station, Clearance Form “A”, along with 19 Order (train order issued by radio to train or engine), with specific limits (from /to crossovers, with milepost) were issued to affected movements to operate “against the current of traffic” that is, most of the old B & A was ABS territory, with established by timetable direction of traffic, TK 2 was eastbound, TK 1 was westbound.

I hope I cleared up my previous comments.

My main point (and the the one in the B & O article), was that running train orders, on track obstructed, out of service track was serious business and everyone should be aware of exactly what your 19 Order implies in relation to operating your train and/or engine.

My Great, Great Uncle Mr. Dennis Ryan was a Civil War Veteran, who got “Drafted” into the Confederate Army when he got off his Sail Ship from Ireland in 1862. After the War was over, in 1865. Dennis Ryan took a Job as a Laborer for the Railroad in Kentucky and worked his way up to Madeira lying track. On Camargo Road he saw a Big White Farm house being built at which he asked the Builder: Mr. Black. If it was For Sale and they agreed on the price, completed the deal. Which is now my home…

I wonder if the Mr. Priddy you spoke of was the Mr. Richard (Dick) Priddy that I knew years later when he was director of government relations for CSX in Washington DC. Dick was a long-time B&O man and was very kind to me as a relatively new AAR employee. He knew I was interested in railroading beyond my job responsibilities and often invited me and my family to ride passenger specials out of DC, and even invited me to ride one of the steam specials from Cumberland MD to Terra Alta WV, up 17 mile grade, unassisted. That amazing trip began with an inspection of the cab of the 614. I have one photo of him smiling broadly, enjoying the ride in the rear seat of the last car on that train, which I’d be glad to forward to you if you send me your email address.