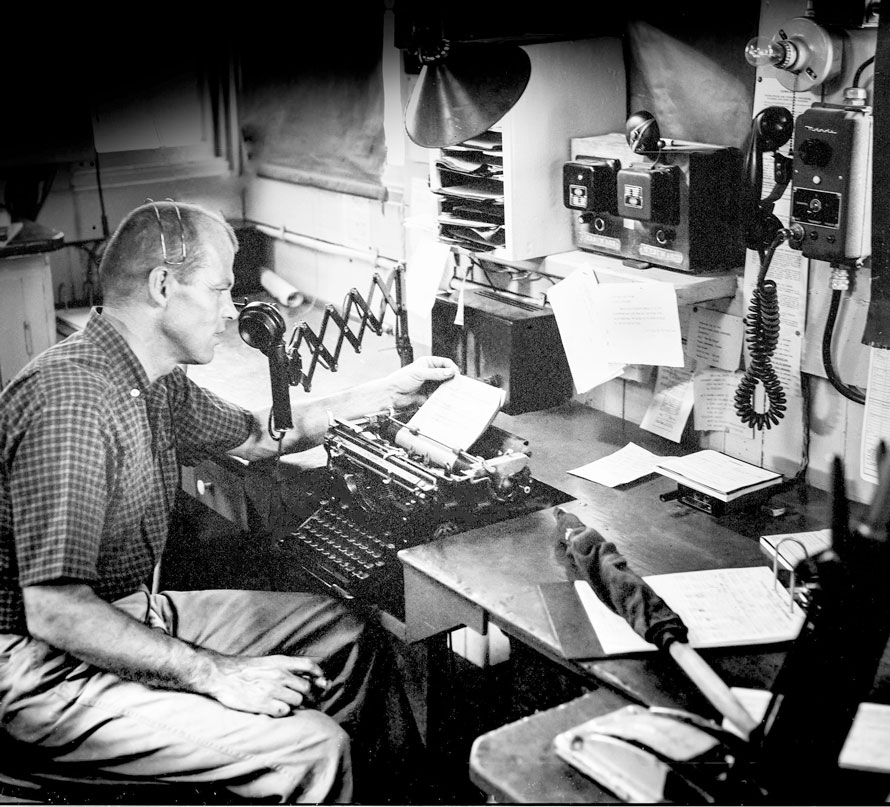

This is Dale Bryan, thirty-three-year-old Southern Pacific relief second-trick telegrapher-clerk at Paso Robles, California (Paso de Robles/pass of oaks) on a warm July evening in 1960. And these are the tools of his trade:

Clockwise: earphone; scissors phone; shelves for 3-, 5-, 7- and 9-copy blank train-order forms (with carbons at the ready); dispatcher’s loudspeaker; westbound and eastbound annunciators (‘bells’); Motorola radio; clearance cards; telephone line ‘jacks’; ‘O.S.’ sheet; levers for westbound and eastbound train-order semaphores (‘order boards’ on the SP); a red flag and of course a classic Underwood typewriter. Although he is still referred to officially as a ‘telegrapher,’ Dale no longer has Morse code in his job description: the key and sounder were removed three years earlier. The new-fangled Motorola is the future of train control.

By 1960 Paso Robles, with its single overhead bulb burning in the dark, was the only fully-open, 24-hour train-order office remaining between Santa Margarita (which is north of San Luis Obispo and at the foot of the Cuesta grade) and King City. This is a distance of 75 miles.

What I remember is the understated manner with which Dale handled his duties while engaged in a great enterprise with all its dangers and opportunities to make consequential mistakes. Train-orders on single track were often about taking time from superior trains and lending it to inferior ones. Dale needed to transcribe his dispatcher’s orders quickly and with complete accuracy because as little as a typo would invalidate the order and stop a train. What’s more, that error would be magnified over distance causing further delays and recalculations up the line. No pressure then!

And Paso Robles’ annunciators gave minimal warning. How much ground did No. 99, the westbound Coast Daylight, cover in two-and-a-half minutes? The classic Hollywood films High Noon (Gary Cooper) and Suddenly (Frank Sinatra) drew on the dramatic potential in a rural California station like Paso Robles. Cue the ticking clock and the unseen inevitability of a fast-closing express.

The railroad will always be about time and distance

It’s worth remembering that the railroad in those days didn’t run only on rails. It ran also on an invisible matrix with real people passing detailed computations of time and distance from one to another. And these computations were of great importance, since the railroad was literally the main line of commerce and communication.

Now I guess it’s only natural that the sight of my old friend at his operator’s desk sixty years ago will shout analog, even if many of us do find historical railroad technology important and interesting. But whether analog or digital, steam or turbocharged diesel-electric, the railroad will always be about time and distance. From this modest station and using comparatively primitive and manually-dependent communications, time was given and time taken away. How many people could put that in their job description?

Robert Field – Photographs and text Copyright 2020

As the son of a towermen and a volunteer at the SONO switch tower museum this was one of best story’s about what operators did the picture and description is spot on. You missed nothing. Anyone that knows about tower and block stations would agree. Thanks for sending this in.

Thanks, John, appreciate your comments. When you walked in to one of these rural stations and heard the ticking clock and the rail joints creaking in the Summer heat….you didn’t need a train, you simply knew all was right with the world. I’m sure that something like this will still happen on the railroad, but in a different form and not in a way that’s so accessible to the public? Robert

Because of 911 much has changed Robert. Even taking pictures in dispatchers offices is frowned upon. Towers are all gone here where I am. With the help of a friend we have a working display for the public to see and listen to.,

John

Great story. Worked on the road where train orders ruled our way of life. It was daunting hanging out on bottom steps of a locomotive/caboose grabbing orders on “the fly”! Wish I could do it one more time!

Hi Jim, you know, I felt for the crew of a train that got a restricting train-order (or a ’31’ as they were called in the East). No warning other than a red train-order signal; fireman grabs the order, removes it from the string, then quickly crosses the cab; engineer reads the order & then stops the train, maybe all within no more than 100 yards from the order-mast to the fouling point with the passing track. I guess this is why dispatchers avoided restricting orders where possible, but it does show the tension that took place behind the scenes. Thanks again for your comment. Robert

Robert did you work on the railroad?

So far as I remember I’d finished the first trick & had a bite to eat, then talked Dale into having his picture taken. Summer job, learning curve!

A “31” order required the signature of an engineer or conducted and could not be delivered on the fly. The rule for the “31” order in the ARA and AAR rule books and as adopted by subscribing carriers was quite clear on this matter. Only a “19” order could be delivered on the fly.

As for a train order being received immediately before it becomes geographically effective, that would be considered a restricting train order and the train would have to stop and the condr or engr sign the order to acknowledge receipt to assure safety and integrity of the process.

To allow a train to pick up such an order on the fly is an immediate hazard and extremely unsafe.

As comment, I was asst mgr of operating rules on SP prior to the UP consumption of SP on Sept. 11, 1996, and was a train order train dispr on the San Antonio Division going back to June, 1972.

It wasn’t always necessary, but we were able to make as many as 11 copies of a 19 order using double-sided carbon paper. Yes, it could get very stressful! Boston division, Penn Central/Amtrak/former NYNH&H RR Shore Line, 1975-1989.

Thanks for your comment Fred, yes the extra copies and fiddly carbons made it more difficult especially if the operator was in a great hurry. On the SP the additional copies were for a second Conductor (if the train was very long) or for a helper, e.g. for the hill at Cuesta. There was a slot on the ‘speed’ order frame for hanging the extra set of orders. In Morse days of course there was the key to deal with as well as the typewriter, more-or-less together! Of course, once armed with these skills, an experienced telegrapher-operator could travel the country (and Canada as well) working where he wanted for as long as he wanted. You could almost call it a kind of universal language. Robert

My brother, Bob Hughes, would have loved this story.

Yes he would have. He wrote some very good stories and I enjoyed his company at the tower in Norwalk. We all miss him very much.

Good to hear Sharon, thank you. Robert

Thanks, Sharon. We will be remembering Bob and reprinting one of his stories next Thursday (Christmas Eve) so be sure to check back then.

Very well-detailed capture of a time and profession that was on its way to extinction. The explanation of what the items are in the image of the operator’s bay has huge value for those who missed out on these scenes. The spirit of the great railroad writer Harry Bedwell and the SP he knew is not very far away. Thank you for putting this in print.

Thank you Robert. Yes the Harry Bedwell stories were authentic and fascinating and the accompanying illustrations and drawings were excellent too. I suspect today some of these illustrations would be classed as in the ‘Norman Rockwell school’? They wouldn’t have been possible without a large audience for whom the railroad was a part of everyday life. Thanks again Robert for your comment. R

What is the wall-mounted light bulb next to radio handset? On other railroads lights above the desk would indicate block occupancy to give the operator a heads up. Could that be what this one is for?

Yes it is. I imagine it will date to before the SP installed ‘annunciators’ on the desk. These could fail, so it was kept in place. It has a cord-pull so the light can be turned on and off. The Santa Fe I think didn’t use ‘buzzers’ so the only warning was when a light like this went on, silently of course. One other thing: Dale didn’t really need to use a head-set and a scissors-phone at the same time. I asked him to do this for the photograph and, being a kindly-disposed young man, he agreed. Thanks for comment.

The light bulb was wired in series with the lamp on the Train-Order mast. To let the operator know if the lamp had burned out.

The Operator was more the, hands, eyes and ears of the Dispatcher.

The Dispatcher was the one that was doing all the calculations and seeing the bigger picture.

It was the Dispatchers railroad.

Ray Eiser

A train crew would be quick to tell you on the radio if the semaphore light had burned out. Signal maintainers changed them out on a regular basis so a dud bulb shouldn’t happen. I don’t remember ever ‘testing’ a semaphore bulb.

The annunciator is sitting on the shelf in the pic. Other SP train order offices have the socket without a chain. Also trains did not have radios until the late 1950’s.

As I said the bulb was wired so of one or the other went out they both went off.

I’m approaching from an SP prospective.

As that is the railroad I have interest in.

Ray Eiser

Regarding semaphore signals with lamps burned out, at night, if the position of the blade can be seen by the headlight of the locomotive, the signal aspect will be respected.

AAR Rule 27 as revised January 17, 1928: “A signal imperfectly displayed, or the absence of a signal at a place where a signal is usually shown, must be regarded as the most restrictive indication that can be given by that signal, except that when the day indication is plainly seen it will govern . . .”

Cool,

SP Rule 221 (Pre 1976)

Paragraph 9

“When light is not displayed in train-order signal at night, report must be made from next open train or the office, unless special instructions provide that light will not be displayed.”

221 also went by position of the arms of the train-order signal. Unless light-type.

The bulb was more a convenience for the operator as you could not always see the lamp from the operators bay. It also had a side benefit of lowering the current of the series bulbs to extend the life of both bulbs.

Ray Eiser

Very nice pictures. Brings back a lot of memories. I worked as an Agent/Operator for the B&O for a few years in the early 70s. Almost all the orders I copied were hand written with a stylus on the onion skin/carbon sheets with a sheet metal backer. Only “standing” orders that would be issued to all trains during the shift were typed.

Where are all those gray underwood 5 uppercase typewriters? You can’t find them anywhere unless they are stored somewhere locked up