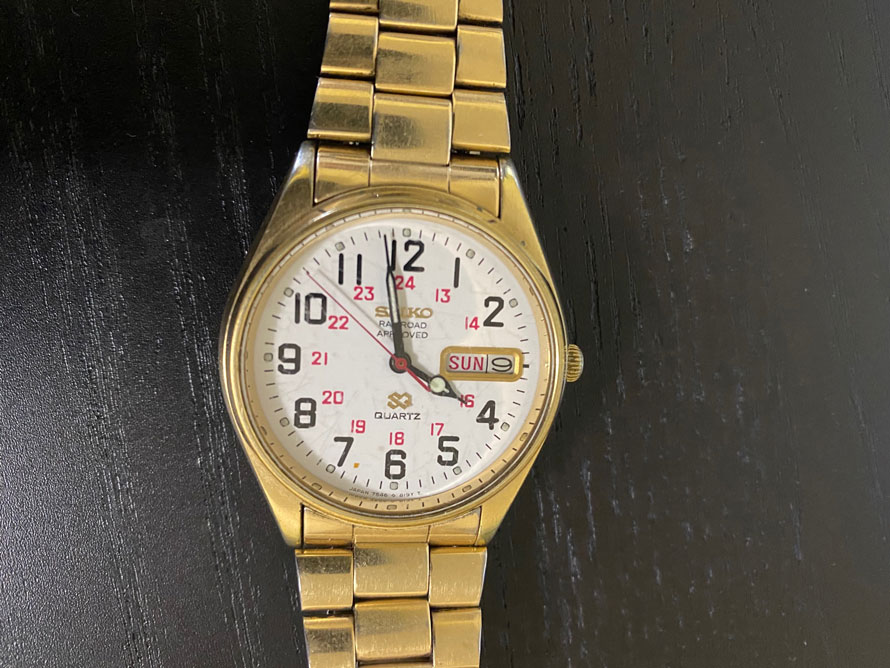

Not long after I joined the Association of American Railroads’ Research & Test Department, I decided that I needed to have an official railroad watch. My wife bought me a beautiful old Hamilton 992 with the Pioneer Zephyr engraved on the back of the case to celebrate my new job. But I only had one suit with vest pockets so I couldn’t wear it to work very often. Many of the railroad people I had met wore a Bulova Accutron or a Seiko railroad approved wristwatch and, well, I wanted to have one too. So, during lunch breaks I visited some jewelry stores in downtown Washington, DC, and one day found one that had a Seiko on sale. I got my watch and was quite proud of it too.

Not long afterwards, I rode the Crescent overnight from DC to Atlanta, Georgia, and met up with a fellow from the Southern Railway’s Research & Test Department to inspect some vegetation control test trackage in southern Georgia. One of my responsibilities in the AAR R&T Department. was to keep up with EPA’s regulations on the use of pesticides like creosote and weed sprays. It was a terribly hot and humid summer’s day, but we were in an air-conditioned car heading south on I-75 toward Cordele. All of a sudden, he exited the interstate and pulled into a very small town. Seeing no railroad tracks, I asked where we were going. His response was that he was hungry. Okay, I thought, I could eat, too. No problem. He drove through the tiny town of Pinehurst, but I didn’t see any restaurants. He drove out around back of the three or four buildings that comprised the town center, and parked by a field of watermelons, big and ripe. We climbed out of the car, and, to my amazement, he picked up a melon and threw it to the ground, breaking it open. He picked up a piece of the reddest, juiciest watermelon I’d ever seen and started eating. I was dumfounded. Then he told me that he owned the field. I suppose I should have guessed from his accent. We finished the delicious melon, got back into the car, and headed to the test area a few miles away.

We spent the next few hours looking at sections of right of way where different herbicides had been applied and he made notes about his impression of their effectiveness. The heat was oven-like, and the humidity was oppressive. We were in and out of the air-conditioned car all afternoon. We were finally done late in the day, and it was time to head back to Atlanta and a cold shower. I glanced at my new watch but was startled that I couldn’t see the face. The glass was fogged up and drops of water were on the inside. I exclaimed “it’s raining in my watch”. I was crestfallen. My new railroad approved railroad approved wristwatch was defective.

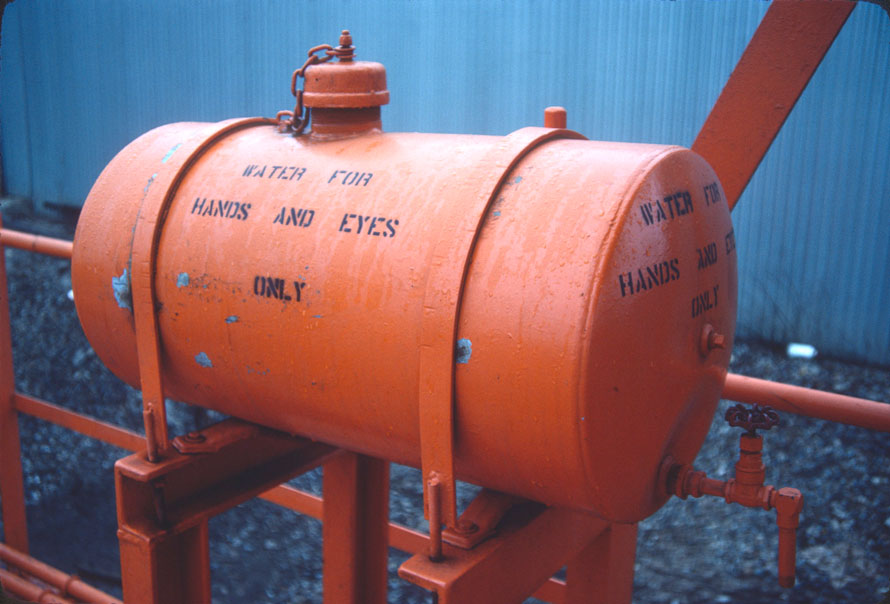

After returning to Atlanta, I went out the next day to observe the vegetation control operation along the mainline between Atlanta and Chattanooga. I left my wet watch in the hotel room hoping it might dry out and headed out to the yard early in the morning. The Southern had its own weed spray train and the Engineering Department ran the spray equipment. It was a short train; a few tank cars of the weed spray mixture, two flat cars for the spray crew and equipment, one engine and a caboose. It was a foggy morning in Atlanta and rain was threatening. The spray train crew had little shelter on the open cars. The train was already assembled, and final preparations for the day’s work were being made. The diesel-powered pump was clogged with scaly debris and the crew was busy cleaning it out. Once everything was cleaned and back together, we were off.

Weed spray solution was drawn from the tank car and pumped from the lead flat car carrying the diesel-powered pump and hoses to nozzles mounted on both sides at the trailing end of the second flat car and operated with compressed air from the train line. The two-man crew on the forward end of the car operated the nozzles. Standard operating procedure was to stop spraying when approaching waterways and grade crossings, so the crew had to keep a close watch of the track ahead so they could quickly shut off the spray. It was a pleasant and interesting morning riding along out in the open. Kudzu vines were abundant, and stories were told about its rapid growth over buildings and old cars along the right-of-way. The rain held off as I rode along watching the operation until being dropped off at Dallas, Georgia, to catch a ride back into Atlanta.

When I got back to DC, I took my defective watch to the jeweler, who laughed and said it was nothing serious, just the seal under the bezel had failed and between the heat, humidity, and air conditioning, moisture had found its way in. It was fixed that afternoon and I wore that watch for over 30 years. I rarely wear a watch these days, but I keep it going with a new battery every five years.

Peter Conlon – Photographs and text Copyright 2021

What a fascinating account of an almost invisible activity. I am struck by how exposed those 1980’s railroad men were to the herbicide, and would hope that today they would either be in a sealed control compartment or would be wearing protective jump suits, gloves and respirators. Now that would be comfortable on a hot, humid Georgia day!

I too had a Seiko railroad watch that lasted more than 30 years. After my too few years with the railroad, I became a nurse. My watch was better than a secret handshake in terms of being recognized by patients who had been railroaders. I had some wonderful conversations and learned a lot from the old heads.

Thanks for this marvelous story and photographs.

The operators of the spray train were either Supervisors or Management Trainees as evidenced by the white hard hats. I had the privilege of operating the spray gun and coupling/uncoupling the hoses. My first experience was in 1972 from Danville, VA to Richmond, VA which was halted by the arrival of Hurricane Agnes and its aftermath.

I assumed the spray was relatively benign after it spilled on an open cut I had and failed to produce any negative reactions then or later..

The restrictions to spraying were basic e.g. water, roadways (vehicles) and visible animal life. I expanded them to areas where adjacent landowners “improved” the right of way with lawn maintenance, gardens or the like.

This was one of the more enjoyable jobs on the railroad

Great article. The last picture shows the Southern Railway style Whistle Board (alerting trains to blow a warning for an upcoming grade crossing). An engineer didn’t have to know the horn sequence because the sign tells him two blow two long, one short and a final long sound, the last one ending after passing the crossing, as if after doing it tens of thousands of times he wouldn’t remember.

Unless it has changed in the last five years, which I doubt that it will ever change, train crews don’t wear hard hats.

Love this glimpse into the spray trains. I’ve seen one or two moving around but it’s nice to see it from the railroad’s perspective. I too wonder about the crew being exposed to the herbicide but I guess times were different then. Railways seem to spray a lot less than they used to, which is probably good for the environment but not so good for the roadbed.