On the morning of Tuesday, November 22, 1994, a friend of mine who was the environmental manager at the Southern Pacific in Denver, Colorado, called me at my office at the Transportation Technology Center to say that there had been a derailment early that morning on Tennessee Pass. The air brakes on a train load of taconite pellets failed to function after cresting the top of the pass. Almost the entire train derailed on a 10 degree curve, he said, and that there were some injuries but fortunately no lives were lost. I wanted to see the aftermath but couldn’t get away until Sunday morning.

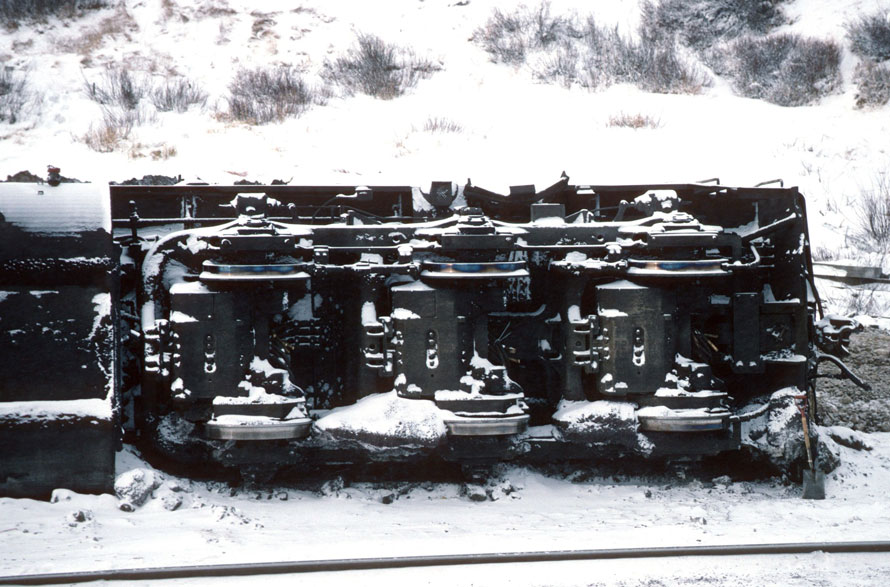

My son and I drove up to Leadville from Pueblo early on a very cold morning, had a bite to eat there, and went on up the road. As we came around a bend, we saw the snow-covered wreck all along the left side of the track. Whatever track damage had been sustained had been repaired but the cars and locomotives still lay pretty much as they fell. I was able to take a few photos, which I thought I might be able to use at our Emergency Response Training Center at the TTC in Pueblo.

From my friend at the SP and other sources, I learned that the train had originated in Wisconsin, probably from one of the ore handling facilities I had seen on an early trip to that area and was headed to Geneva Steel in Utah. It had left Pueblo late on the night before the accident and that it operated uphill all the way to the summit without using its brakes. When the engineer applied the air brakes after setting up the dynamic brakes to maintain a 15-mph speed, nothing happened. No air brakes. Though the locomotive brakes apparently worked, the track was on a 3% grade downhill and the train very quickly reached 60 mph. The conductor jumped and sustained a broken leg, while the engineer stayed on board and was not seriously injured. The lead engine did not derail but the three trailing units and 51 of the 54 loaded cars went off the track. The derailed locomotives and cars were later taken to Pueblo and scrapped.

An investigation later determined that while the train was in the Pueblo, the yard crew had supplied air to the train brake system from the yard air system and that there was moisture in it. That moisture froze during the run up the mountain and blocked air flow in the trainline, thus disabling the air brakes on the cars.

One interesting thing about the accident was that I asked the SP for a cab from one of the locomotives. At the time, I was working to develop a locomotive engineer training program at TTC and thought that the cab would be a useful addition to the program. We were planning to use computer generated imagery to simulate various train operations and I had visited some other railroad training facilities where they had created a very realistic system using cabs from retired locomotives. In fact, one training officer told me that it was so realistic that one of the old heads actually spit tobacco juice out the window during a simulated run inside the training building. Anyway, the cab from DRGW 5370 sat for a while in the former Missouri Pacific yard where the scrapping work was taking place in Pueblo before being brought out to TTC, where it sat for a while longer before it was finally returned to the scrapper when my training plans failed to materialize. But that’s another story.

Peter Conlon – Photographs and text Copyright 2022

At first, I thought these were B/W photos until I could make out the blue truck and yellow side-boom tractor….and the red hard hat of a worker. The Pass would officially be shut down to rail traffic about three years after this derailment. I suppose like Saluda Grade in N.C. this scenic stretch of railroad will never see another train. Thanks.

I remember we used a brake hose with a metal ball built into it that was filled with alcohol and from the engines back the vapor went through the train line to prevent this from happening. The crew was very lucky.