I

Railroad architecture isn’t only stones and cement, iron and steel, vertical elevations and so on. It’s also the spirit, or as we may say, the ‘atmosphere’ of the place. And equally, it’s the culture of the lives that have used it.

If therefore you wanted to know more about major railroad stations with a long history, you could do worse than listen to the opening clip from a radio program called Grand Central Station. The program was sponsored by the Pillsbury Flour company and it aired until 1954. Every week, the listener was drawn into a world where the railroad and the station building intersected with human life.

The program began with a voice-over:

“Drawn by the magnetic force of the fantastic metropolis, great trains rush toward the Hudson River, sweep down its eastern bank for one hundred and forty miles, flash briefly by the long red rows of tenement houses south of 125th street, dive with a roar into the two-and-one-half mile tunnel which burrows beneath the glitter and swank of Park Avenue, and then—with a squeal of brakes—Grand Central Station!“

. . . stations in those days were the classic locations for separation and homecoming.

Wasn’t that a remarkable thing to hear on an otherwise mundane Saturday morning? You could be driving somewhere on the West Coast or across the open plains of Nebraska or the Dakotas, but the radio sound-effects of the tunnel under Park Avenue took you straight into Grand Central itself. And once ‘arrived’ under the vaulted roof, a myriad of individual stories passed in front of you. Which one would you be presented with on this particular morning?

The majority of these tales were decidedly heart-warming and today this might sound a little (even more than a little) dated to our ears. But it’s worth remembering that these people had just been through a world war and to my mind this experience was reflected in the way they perceived their built environment. This is because major railroad stations in those days were the classic locations for separation and homecoming.

The other important thing about Grand Central Station is that none of the program’s opening ambience needed explanation. The program wouldn’t have existed without instant public recognition of the railroad environment in which it was set. None of its basic assumptions about the drama and the grandeur of the railroad atmosphere needed spelling out. And this was because the epic nature of this ambience was part of the texture of everyone’s life.

Now as it happens no one has written better about large stations than the novelist Thomas Wolfe, who thought the voice of time murmured along their walls, ceilings and concourses. I have always thought that Wolfe’s depiction which follows is an imaginative amalgamation of Grand Central and Penn Station:

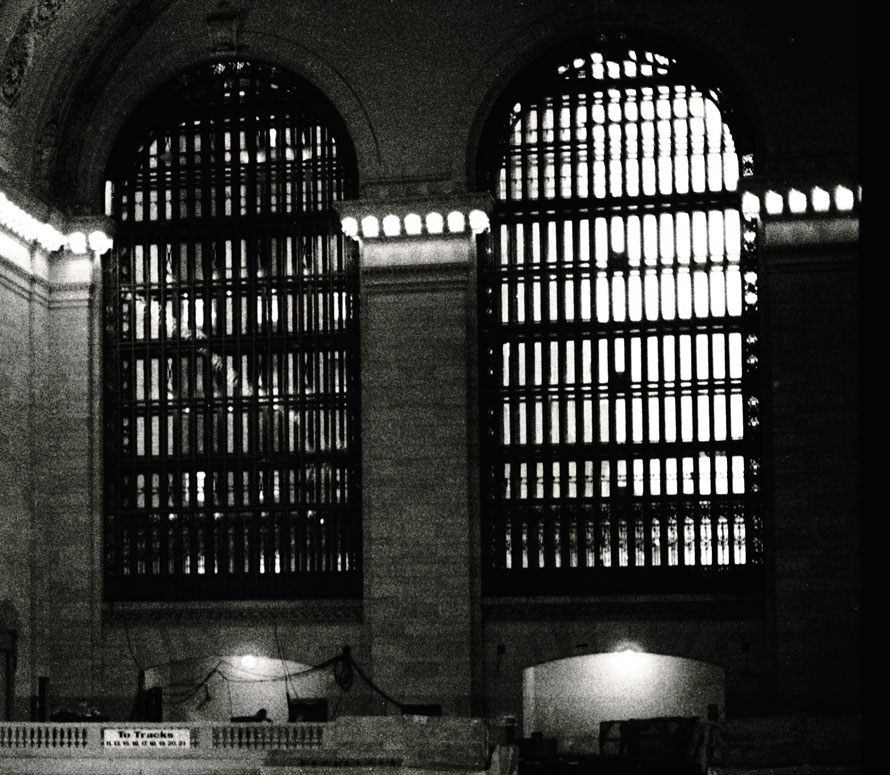

“The station, as he entered it, was murmurous with the immense and distant sound of time. Great, slant beams of moted light fell ponderously athwart the station floor, and the calm voice of time hovered along the walls and ceiling of that mighty room, distilled out of the voices and movements of the people who swarmed beneath. It had the murmur of a distant sea, the languorous lapse and flow of waters on a beach. It was elemental, detached, and indifferent to the lives of men.

Few buildings are vast enough to hold the sound of time, and . . . there was a superb fitness in the fact that one which held it better than all others should be a railroad station.” – Thomas Wolfe, from You Can’t Go Home Again

The moted light spoken of so memorably by Wolfe shared a vision with the Pantheon in Rome, evoking something mesmerising about the idea and the unfathomable reality of Time. What I particularly remember about old Penn station was the staircase which took you down one step at a time into the cavernous interior. In those days passengers seemed to walk and not to run. Partly, this was because of the heavy coats and the hats that they wore—the women with the added impediments of high-heeled shoes—and partly it was because many passengers carried large suitcases in view of their long journeys by rail. Everyone milled, they didn’t rush. As if borne by a magnetic force. It was like stepping into a rehearsal for eternity.

II

Located at the end of the transcontinental railroad across the Bay from San Francisco, Oakland Pier was one of the most memorable and unusual of the large stations. (It was disused after 1960.) Here there was the sound of the sea and of many voices beneath the Southern Pacific stained-glass window, a window on the sea and infinity: or better, a window on infinity and eternity. This window has always reminded me of the poem by Edwin Arlington Robinson, Luke Havergal.

Go to the western gate, Luke Havergal . . .

No, there is not a dawn in eastern skies

To rift the fiery night that’s in your eyes

But there, where western glooms are gathering,

The dark will end the dark, if anything. . .

The passengers look both ways, towards the Continent and towards the sea.

When we look at this scene today, we recognize something that in those days everyone knew in their minds, even if they didn’t voice it. The railroad, when all is said, is fundamentally about time and distance and (in North America especially) about infinity. We had a glimpse of our own destiny as we stood beneath that bright medallion, waiting to board our ferry to the other side.

The sun, by the way, never did set on the 13,000-mile Southern Pacific system. It simply wouldn’t dare.

III

It was pointed out to one of the producers of the Grand Central Station radio show that the building should be called a ‘terminal’ and that there were no steam locomotives anywhere near it, although they could be heard in the audio background to the show. He replied to the effect that ‘everyone has their own Grand Central,’ a statement that is every bit as valid today as it was then. Grand Central is still with us. The Pennsylvania station colonnades and Oakland Pier with its overarching wood-and-iron train shed are long gone. But I believe that the vanished architecture of that built environment remains still within the part of our psyches dedicated to meeting and parting. Large railroad stations take on new attitudes and aspects of modern culture but they also bring with them the collective feelings of days gone by. Stations today may be viewed by some as utilitarian jumping-off points, yet there is no doubt in my mind that the Thomas Wolfe view of great railroad stations remains a part of our collective experience and memory.

Robert Field – Photographs and text Copyright 2022

The radio program name may be part of the reason so many people can no ot get Grand Central’s name right. Tiresome.

There was another old radio show from the same era…1948 thru ’54. “The Railroad Hour” was sponsored by the Association of American Railroads. It was hosted by Gordon MacRae , and came on “every Monday night”. Basically, a musical variety show featuring popular performers from that era. Eventually cut to a one-half hour format. Killed off by that wonder of wonders…television !

You’re right Greg, of course, I’d completely forgotten. It does show you how much the railroad was entwined with peoples’ lives in those days, even if it was a sponsored program. Robert

I never got to see the Oakland Pier, but I spent a lot of time at Grand Central as well as some time in the now-lost Penn Station. Everything that Thomas Wolfe wrote abut a big train station was, and even still is, true. Kudos on both the marvelously evocative essay and the wonderful photos.

Many thanks John. These are very strong memories and I think they never leave us. Robert

I started going to GCT almost 60 years ago when I was a kid, I worked in and out of there from 1970 till 1983 and saw how dirty it was and saw how it got a major facelift and was saved because of Jackie Onassis. Your story is a great tribute to this grand station.

John, I also remember that the interior of Penn Station (or ‘Broadway station’ as I used to call it (am I alone here?) was papered with advertisements (some even lighted) in the late ’50s, also true to a degree of Grand Central. There was still a lot to see and experience, but Inevitably this did obscure some of what the architects had intended, especially where GC is concerned the magnificent display of light you see in the Hulton picture library (now Getty library) images, with the ‘suits and hats’ swarming beneath. IMHO the top station picture of all time is Alvin Langdon Coburn’s of ‘Station roofs, Pittsburg’ c.1910. People tell me I have a romantic streak, not surprising as we both lived through an age which in some respects was very romantic. Thanks for your comment, also for the reminder about Jackie Kennedy Onassis. Robert