August 11, 1982

My first assignment after joining the Association of American Railroads (AAR) Research & Test Deptartment (R&T) at the end of 1977 as an environmental specialist was to support the development of national noise standards for the railroad industry. We measured sound levels of locomotives, retarders, car coupling, load testing, refrigerator cars, and other noise sources at several railyards around the country. I’d like to share with you some images from one of the yards we studied: Southern Railway’s Brosnan hump yard at Macon, Georgia.

With Precision Scheduled Railroading (PSR) the latest plan to improve rail service, hump yards are beginning to disappear. At one time, there were about 120 around the country. With the increase in the use of unit trains, which don’t require in-route switching, many yards were being bypassed. With the recent shift to PSR, numerous hump yards have been converted to flat switching yards or downgraded to storage of excess cars and locomotives. In this article, we’ll visit the former Southern Railway’s Brosnan Yard in Macon, Georgia. Some of the photos were made over a week in cold and cloudy February, 1978, during our early noise measurements and others in hot and humid August, 1982, on a trip of the American Railway Engineering Association’s Environmental Engineering Committee. I’ve tried to describe here what I saw at Brosnan Yard and include a brief explanation of hump yards in general.

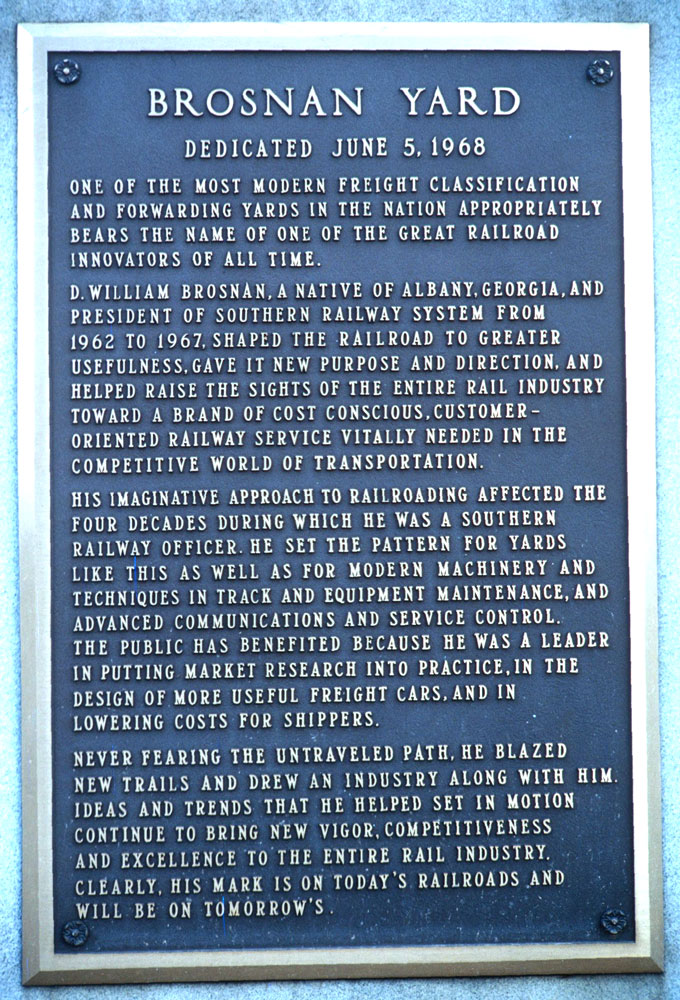

Brosnan Yard, named for Southern’s illustrious president, D.W. Brosnan, was dedicated in 1968 and was a very busy place for over 50 years.

The key feature of a hump yard is a hill up which a train is slowly pushed and its cars uncoupled at the crest and allowed to roll down into an assigned track in a classification yard made up of numerous tracks to become part of a new train. A locomotive or combination of locomotives would couple up to the rear of the inbound train and once ready, start shoving it up to the hump, producing plenty of noise as the engines load up. A list of cars in the train would have already been communicated with the yard office and each car in the train would be assigned to a specific track in the yard bowl. Hump yards are graded with a little depression in the center of the yard to help keep cars from rolling out the other end, hence the bowl concept. A pin-puller would have a list of which cars to cut off as the train is pushed over the hump.

The hump master oversees the computer system that controls the car retarders, an external braking system that includes a master retarder on the main track and group retarders on tracks as they spread out in the yard to control the rolling speed, and the switches to put the cars in the correct track. Retarders in operation produce very high-pitched squeal as the brake shows squeeze against the rim and flange of the wheels. Cars rolling down into the yard are nearly silent but when they couple up with parked cars at normally 4 mph (but sometimes faster), the collision produces a startling crashing or booming sound. If the coupling fails, locomotives, sometimes called trim engines, would push the cars from the end of the track at the far end of the yard to couple them together and so the air hoses on each car can be connected.

Once a train is made up, which may involve more than one track full of cars, the string of cars is pulled to the departure yard. The road locomotives are coupled to the train and an end-of-train device would be attached to the coupler and air line of the last car. A compressed air line from a stationary air compressor in the yard may be connected to the first or last car to charge the train’s air brakes or the road locomotives may be used to supply the air. Car inspectors examine each car on the train to ensure that there are no obvious defects and to check the application and release of the train brakes. Once everything is satisfactory, the train is ready to depart.

But there is much more going on in a hump yard. Trains entering the yard are guided to a receiving yard in preparation for the humping process. The road power is uncoupled and sent to an engine servicing area where the locomotives are inspected, fueled, traction sand reservoirs refilled, cabs cleaned, ice water replenished, windows washed, and minor repairs made as needed. More serious problems mean that a locomotive will be moved to a locomotive shop adjacent to the yard or moved to a shop at another location on the railroad’s system. Locomotives idling in the service area produce low frequency sound that can transmit over long distances. These days, automatic engine start-stop technology on locomotives reduces the amount of time that engines idle, but back in the last century, it was common for engines to idle for hours and sometimes days on end.

End-of-train devices are stored, checked, and distributed from a shop in the yard. Before EOT’s, caboose tracks were maintained to clean and replenish supplies on cabooses. Back before end-of train devices, arriving caboose would be moved to a caboose track to be cleaned and serviced. Freight cars needing repairs are moved to a car repair area, typically called a ‘RIP Track’ (Repair in Place) or ‘One-Spot’, where most any repair to the running gear and safety appliances car be made. Train crews have facilities for preparing for their trips or filing any reports at the end of their runs. Other maintenance crews such as bridge and building, communications and signal, etc., generally have areas of the yard for their equipment and buildings. Another rapidly disappearing feature is the wreck train, which is seen in the last couple of photos.

Brosnan Yard was another casualty of Precision Scheduled Railroading. The hump was shut down in 2020 and the yard was converted to flat switching. However, as this article was being completed, Norfolk Southern announced that it was reactivating the hump operation, citing traffic increases in the southern region and the need to free up yard crews to help relieve crew shortages. If there’s one thing for sure in railroading, it’s that it is always changing.

Peter Conlon – Photographs and text Copyright 2022

Thanks you so much! Interesting!!

Peter,

Great story and pictures. Everything you said is spot on, I hired on the Penn Central and was set up in 74 and worked the hump in New Haven Connecticut. I will be honest and tell you I never cared for those jobs very much and preferred to be out on the road 🙂 we had 2 engines around the clock working back then, today there is nothing. Thank you for bringing back memories. They still have a hump in Selkirk NY where I did run freight trains in and out of for a number of years and the engine house up there did have all the noise you described!

Thanks for your comments, John. I appreciate hearing that I brought back some memories, even if they weren’t as fond as running on the main line.

An excellent essay on hump yards, where the work is done. Not as glamorous as a hotshot blowing the pigeons off the depot roof at 60 per. But without the humps and flat yards, no hotshot.

Interesting about how humps get reborn. If the normal traffic volume decreases, send more work to the hump There are ways to do this!

Jack, Thanks for your comments. If only you and I were running the railroad…

Thanks for the great insight into hump yards. We still have an active hump at CN’s Symington Yard here in Winnipeg, one of the few left running in Canada. It’s amazing to watch the cars quietly roll down the hill by themselves.

I went to Symington Yard and the Transcona shops with a great friend from CN back around 1990 or so and have been thinking of writing a short story about that trip. Thanks for your comment and I’ll start drafting that article soon. Pete

Thank you, Sir, for the insight on a rarely seen or explained part of railroading.

I’m glad you found this story interesting, Ed. I’ve been to quite a few big yards and shops that few people get to explore and will write about some of them as I scan the old slides.

Thanks pete, brought back lots of memories. This was my home terminal for thirty one year, I became a qualified trainman in 1977 then a car retarded operator and then a yardmaster for The last twenty three years.

Ted, I’m pleased that you took the time to read the story. Only being there for a few days many years ago was a bit of a challenge to write about. Hope I got all the facts right. I always enjoyed spending time with the fine people on the Southern Railway. Thanks, Pete

Great article, Pete!