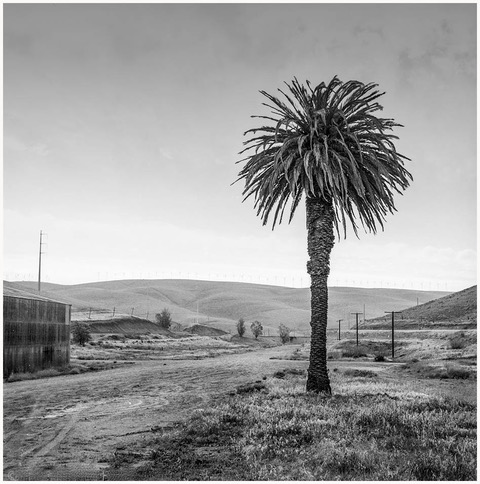

It’s the last day of November in the foothills of the California Sierra-Nevada and remarkably warm for the time of year. The station-board by the main line reads “Rocklin.” There is no longer a station building here but you can usually spot the location of a former Southern Pacific station by the presence of a mature palm tree, and in 1957 Rocklin has a fine specimen.

At one time, this was a staging point for the long climb to Donner Summit, but its roundhouse and its busy turntable are long gone. In 1957 Rocklin is a quiet, peaceful and unspoilt place. (Today, in 2022, there is an elevated highway interchange at this location.) On either side of the tracks a few wildflowers mix with the tall grasses, including some California poppies which have been dormant over the hottest months of the Summer. Jointed rails creak in the midday heat.

Two societies have chartered a special train with the last operating cab-ahead 4-8-8-2 to Reno, Nevada on November 30th and returning on December 1st: the now-legendary “Last Cab-Forward over Donner Summit.” The locomotive has been attached at Sacramento, and at Rocklin the wait for the train is made longer by the extra-board rear brakeman (a man more familiar with freight service) neglecting to initiate the running brake test. As instructed by Mr Harjes, the road foreman, who is in the cab, the engineer has had to do the running test for himself, bringing the train to a firm halt a few miles up the line. There is time to take up a camera position in the cut at Rocklin and listen to the grasses rustling in the autumnal breeze. There is certainly a hint of winter: already there are patches of snow by the right-of-way.

Just a few more minutes and a battered pickup truck bumps over the grade crossing and stops in the rustling leaves not far from Ruby’s Variety Store on the other side. The netted swing-door slams shut and bounces once or twice. The driver doesn’t know that what is about to happen at Rocklin will never happen again.

You don’t see the yellow steam headlight at first because it’s lost in the shimmering heat-haze. Then the wig-wag at the foot of the cut begins laconically to swing and ding, a classic “Hollywood film” sound which despite its ridiculous understatement—or perhaps because of it—never fails to be exciting. Mr Sorensen is using his steam whistle now. The locomotive also has a powerful air horn but at this speed the steam whistle is electrifying and now the ground is literally shaking, making you wonder how you will hold the bellows camera (already vintage in 1957) with its tiny viewing glass steady enough to get a shot. Then in seconds they are past, the rolling stock rocking in a cloud of roadbed dust, the locomotive canting upwards at the beginning of the stiff grade that will take them all the way to the Summit. Wheel-clicks fade and the very last thing that you hear, oddly enough, are the whistling compound air-pumps of an AC 4-8-8-2 receding into the distance.

Another minute, and when the grasses have stopped rustling and the air has settled, the door of Ruby’s Variety Store swings open and the pickup’s driver exits with a newspaper under one arm and a bottle of milk in the other hand. Then the door slams shut and bounces two or three times. Everything is the same again. Jointed rails creak in the midday heat.

But everything has changed.

II

Until the end of the steam age, rail photographers were inclined to see a landscape with a railroad running through it simply as a stage for steam photography. You can understand this because steam locomotives in regular use took on the atmosphere of the countryside through which they ran. Think of the Southern Pacific in California, the Santa Fe in the Southwest and the New York Central along the Hudson River; and we might add Winston Link’s photographs of the Norfolk & Western in the Appalachians as particularly good illustrations of this phenomenon. After all a railroad (whether steam or not) folds itself into the landscape in a way that nothing else can. The railroad and the landscape have always been intimately connected.

But what’s interesting to me about the Rocklin experience in 1957 is a change in perception. I was now registering background details that I might not have seen so clearly in earlier days. From there, it’s only a small (albeit a significant) step to photographing the natural and built environments of the railroad—objects like the Variety storefront—as subjects of interest in themselves. And this is not very different from how we all look at the railroad today as we can regularly see from posts on The Trackside Photographer.

Ours is not, of course, the railroad world of 1957. We do live now in a world of contingency and circumstance rather than in one of the dramatic event. Today, we aren’t focused so much on awe and spectacle, which in any case may be more difficult to come by now than it was in the last mid-century. And it’s true that such a prevailing ambience of change is not unattractive in itself. In railroad photography, it lends a contextual depth of shadow, twilight and abstraction to what we see.

But the bottom line is that, in any age, it’s not always the “legendary” happenings that decades later stand out most prominently in the memory. The things that we see on the edges of our vision, which may at the time seem insignificant or even trivial, can turn out in retrospect to be just as important as the major events. These peripheral things make a bridge between the past and the present. This is because their disappearance, or their survival, are important to the way in which we measure time, like an old pickup truck disappearing down a dusty road and a statuesque palm tree with a history; things which, as it happens, make up the very stuff of modern landscape photography.

Robert Field – Photographs and text Copyright 2022

Nice pictures…wonderful story. I lived in Reno at the time. I watched this exact train pull into the Reno Depot. I was a young kid. A family friend knew the engineer and he invited me into the cab of 4274 as it sat at the Reno depot!! Lucky kid I was!!

I too have had a similar experience in my lifetime. As a B&O enthusiast I would spend hours milling over B&O books full of those wonderful scenes of steam locomotives at various locations around the system. Once I got a license, I spent the last two decades of the B&ORR photographing the same scenes that I had seen in books from two and three decades earlier. I was amazed at the changes that had occurred in 30+ years. CSX has been in charge of the former B&O now for over 35 years now. What was, when I was photographing the B&O has radically been changed. Yards have disappeared, foliage that wasn’t, now is, in abundance and even mainlines have disappeared. Yes, I can totally relate to what was and what is now.

Classic steam engineers were softly-spoken, dignified men, the very models of easy, confident masculinity. It was something about the job, and Mr Sorensen was not an exception to this rule. I can’t think of another occupation that did that to the same degree. The westbound man was called McClintock? Thanks for the kind comment and I’m glad this brought back a few memories. It’s become kind of a famous event.

Yes definitely on the same wavelength & I’m guessing we’re not alone. Over the years I’ve had to accept that almost everything changes over time, the railroad, its built environment and even its landscape all included. Documenting these changes is well worth doing and can produce ‘time-less’ pictures in its own right. Incidentally the last of the two images was made at Altamont Summit CA in 1991, with the old, lifted SP running through the middle, and the site of Altamont station just beyond the palm tree. It might still look the same as in ’91, or it could be completely changed? Either way, it seems worth documenting.

I, too, experience a slowly evolving enlightenment that comes with age and a continuing interest in the railroad. Most of my railroad photography has been more of the documentary sort rather than any attempt at artistic portrayals. Not particularly interesting pictures. Yet, when I look at my own photographs and those of others, my eyes now tend to look beyond the primary object of my attention and begin to see what’s around in the scene and, maybe equally important, how it makes me feel. Other senses come to life–the smell of the track in summer, the sound or silence of the surroundings when there is no train–the imagination goes to work then. Some of the greats, like Dick Steinheimer, seemed to know that right from the start. I wish I knew about that back when, but I do understand it a bit now. This website, The Trackside Photographer, has helped me to realize that there is much more to this passion than just the train. I am hopeful that someone will step up and take over from Edd Fuller, to give him time to go exploring and to give the rest of us more opportunity to explore our own experiences in writing and with our old images.

I couldn’t agree more! `i especially liked the comment about the sound/silence when there is no train. It did take me a while to get there, but all the same I think it does work away in the back of your mind, to be retrieved later. Thanks for your comment!