“What brings you here?” I was far from home, and the waitress’s warm smile was very welcome. “Well, I liked the sound of the place.” There followed a quizzical tilt of the blonde head, and I had to admit that hers wasn’t an easy question to answer.

Partly, it was trees. Now I love trees; being an outdoor man trees are what I do. And on the map, ‘Woodland,’ a reasonable-sized town in the Sacramento Valley of California, sounded right up my street. A little research showed that Woodland was originally carved from the ancient Woodland Oak Forest. There was even a Woodland Tree Foundation. But there was so much more to what I was doing here than trees. I had shot the Southern Pacific in the 1950s, and grew to like the San Joaquin and northern and southern Sacramento Valley towns with their tall, civic water tanks that you could see for miles. As you drove, there would be a blur of farmland and open space to either side, an unending horizon where yellow met blue…and then a sign…’Woodland’ maybe?

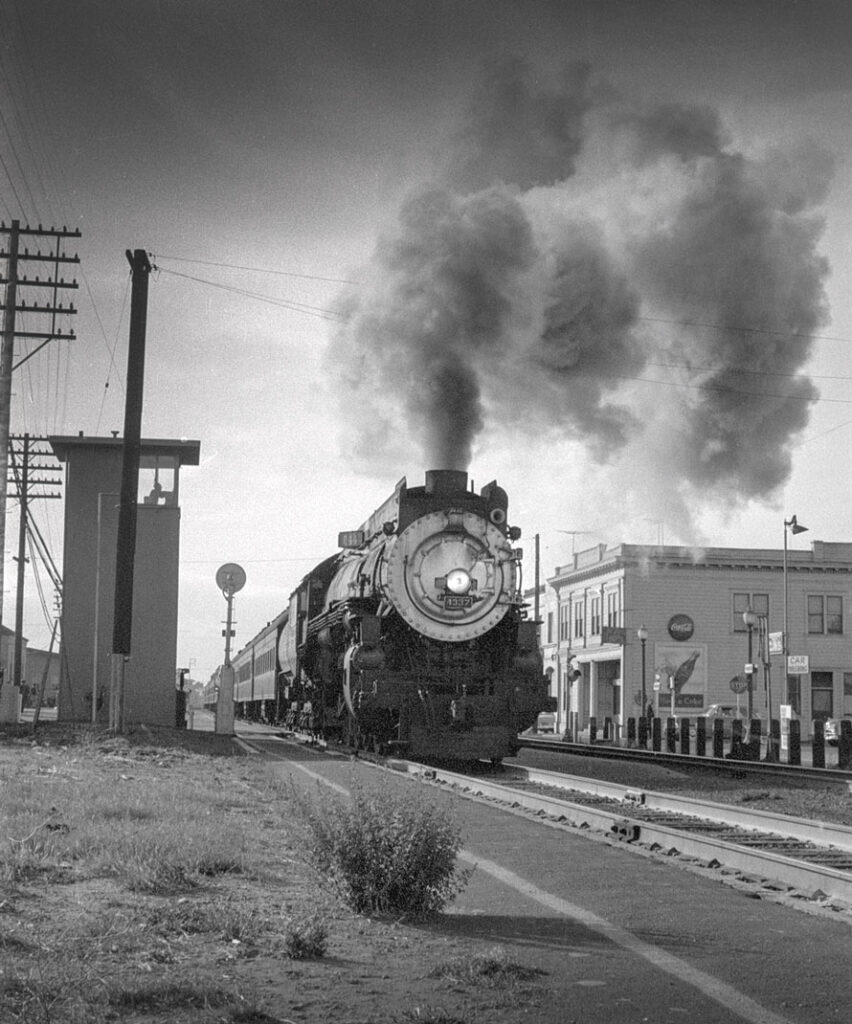

There would be gently proportioned buildings to either side, Spanish architecture with oval doorways, people going unhurriedly about their business and greeting passers-by; there would be intriguing side-streets and cafes. Ahead, the crossing gates would come down, followed by a gentle wait, followed by a steam whistle or a diesel horn and the rumble of a train with multicoloured railroad names on the sides from everywhere in the country.

Then the gates would come up, and the world would begin moving once again, people crossing the road, greeting others, opening the door of the barber shop. I seemed to see them, looking back, becoming history in front of my eyes. Manteca with its endless vistas of flat farmland. Modesto, with its skewed hotel and its ‘Thirties‘ booster sign: “water, wealth, contentment, health.” And Paradise. (Paradise!). Now, in 1992, I wanted to see what remained. “Wait a minute,” said the gent leaning on the lunch counter, “there’s a place forty miles up the road called ‘Williams’ that’s more like what you want.” And in truth, Woodland had lots of blue skies, waving grasses, sunsets, patterns, interesting if modern buildings, clouds. Nice smiles. Not many actual trees. Woodland was large, modern and bustling. The all-important scale of life had changed.

While driving on to Williams in my rented Buick Century (and I put some mileage on that car) I reflected that it isn’t strictly true that landmarks simply disappeared after 1960, or that places became unrecognizable. It is just that when you do recognize something, it has lost its scale, its relative importance and it seems much diminished, so that it’s more real in memory than in existence. To say that nothing was allowed to remain in any one state for any extended period of time without being moved about and reconstructed is, then, not a moral or an aesthetic comment, but a fact. After all, there is nothing to suggest that anything is more than twenty years old. Half the offices and malls (megalopian impositions) have been built since 1980; fifty percent of housing stock dates from 1960, which is, in fact, the cut off point for our time beyond which the past is just the past. Not measured in centuries, but from 1960. We are not talking about demolition per se, or even about recovering a lost reality: but about the destruction, or the death, of scale.

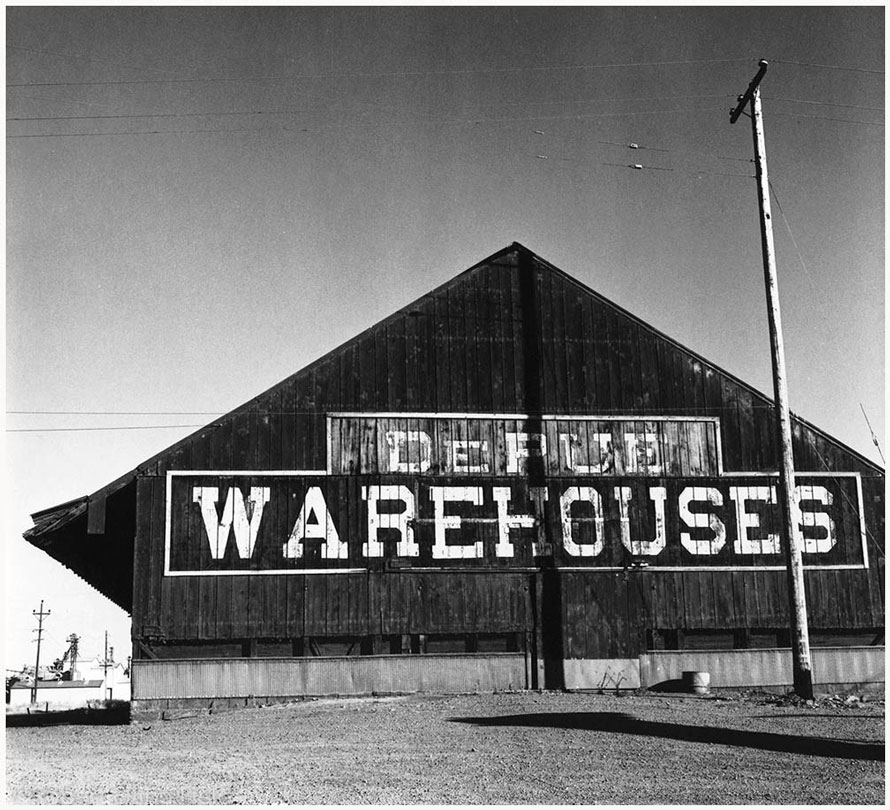

Williams, as I found it, is a place where the eye is not encouraged to linger. This old patchwork of buildings only survives because it is cheaper to buy vacant land for development. The ‘real’ is thus rendered invisible, being off the main flow of traffic and consequently separated from the direct field of vision. It is a town of things which are not.

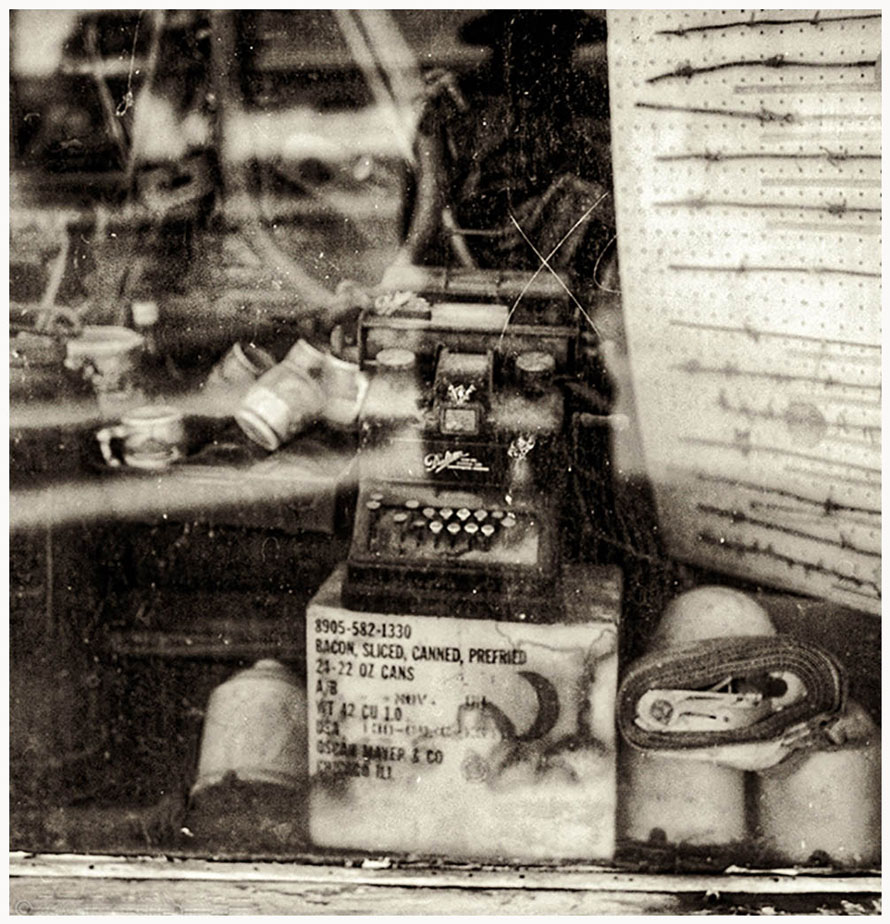

Or to put this in another way, it is a town of real things in a way that other, prefab buildings, or tract houses, are not. It has a texture: there are tactile, wooden, stuccoed buildings of different heights, styles (although the Spanish-modern predominates) and shapes. Every building has a personality, the most notable being the ‘Antigue’ (sic) shop. Shadows and light interact and fall symmetrically across the scene like a kind of sun dial. Vertical offices have internal staircases, so evoking the town banker, the town lawyer.

it is in the photographer’s gift to rescue continuity.

I could see now that there is something deeply sympathetic about this place, much more so than walking into a film set or a theme park. Williams et al. weren’t just places, but ideas. Here there is an essential this-ness, peculiar to North America, which makes a grain elevator, a pile of scrap, something other than it would have been: makes it significant, even artistic. From Acquinas, through Lockeian philosophy, Shakespeare (‘E’en this?….this?) to the present day…..this-ness, the place, the locus, the point in a continuum of life and time; of a landscape, or an argument or a description, and therefore a sense of place, is an important value in the scale of photographic meaning. And what we are seeking in a place like Williams is not a before or an after, but a continuity. And why? Because it is in the photographer’s gift to rescue continuity.

What’s more, Williams in the 1990’s looked exactly like the still-extant remnant of a railroad town –for which read a town built around a railroad running through it in the mid-1950’s, i.e. in the steam-to-diesel era. Rounder-edged and broken elevations go together with the size and elevation of steam and first-generation diesels. There are the obvious things: the architecture; the water tanks; the inevitable palm tree; wig-wags; and the less obvious: a vanished station, the seeming echo of a thin line of Morse code. Telephone wires and poles equal distance, something so simple that says so much, like a radio signal from the space of the past right through to us today. Even structures like an agricultural shed take on an iconic meaning through their past association with the railroad.

The vanished station, which is the missing piece in the jigsaw that is Williams, would have been a study in classic Harriman lines and in kindly and sharp-eyed faces. Target signals, golden fields and palm and eucalyptus trees, spaced for shade in front of clapboard section houses, each with its verandah from which to take the evening breeze. When this was part of the Southern Pacific main line, the Shasta Daylight and the Cascade went through here to the sound of chime-horns and crossing bells, leaving behind the rustling of eucalyptus leaves and kernels and the sound of a prop plane droning overhead. When real time equaled real life and not simply nostalgia.

And there was latent power in that steam-age diorama. As we see it now, steam is fairly sedate, but it could be awe-inspiring and occasionally heart-stopping. One day in 1955 at old San Mateo station (on the Peninsula near what is now Silicon Valley) I was waiting in just such a diorama for an evening express to pass through, when the gates went down and the bells stopped ringing, leaving an unusually eerie silence. An elderly gentleman had strolled confusedly onto the double track and stood facing in the wrong direction. Then the rapid, staccato beats of a locomotive running at high speed were suddenly cut off; the warm, steam-era headlight became an angry beam: and the whistle screamed plaintive, desperate notes into the air. Finally, someone in the nick of time pulled the behatted gentleman away, whereupon a furious engineer pulled back hard on the throttle, thus ripping apart the fire, and the locomotive seemed to leap from the rails. Now events such as this have rightly been called ‘the machine’s sudden entrance into the landscape’ by Leo Marx (The Machine in the Garden, 1964). But is it a disruptive entrance? That locomotive belonged exactly where it was within its classic landscape. Am I alone in thinking that the places where railroad scenes like this occurred retain a special aura?

But beyond all that, there remains something about these places that is simply indefinable and Williams has that indefinable quality. Woodland, Williams and their almost-forgotten sisters may not have retained all that many trees. But they have time, they have truth and they have reality. They are, as you might say, real estate.

On the way back, I stopped again at the Woodland diner. The helpful gent in the battered hat was munching through his late breakfast, and he may be still. And thirty years on, the quizzical, warm-hearted blonde waitress is still smiling. But O the lure of trackside structures! Now let’s see, what would ‘Arbuckle’ be like? Or (wait a minute), ‘Willows…..’

Robert Field – Photographs and text Copyright 2023

Wonderful!! I use to train watch as a kid in Davis. This piece brought back memories. Thanks!!

What a wonderful collection of images and a captivating narrative to boot!

Great story about how things have changed so much. Not all for the better either. Great pictures!

Thanks John. It’s true of course that modern buildings can also be photogenic in an abstract kind of way. Personally though I’d like to have seen a more gradual integration with the ‘old’ instead of what sometimes seemed like a car-crash of change c. 1960; ditto the end of the steam era, with everything concentrated within a short ten years or so. Indeed I think it was the end of steam that made me particularly sensitive to changes in the built environment. One man’s view, of course; others may well see it differently!

Many thanks to you both. Putting this together is a little like a tree falling in a forest (pardon the pun) so it’s always good to know when someone’s on the same wavelength!

The ability of you, and so many who write here, to re-create the “feel” of those times is just incredible! I do not have much knowledge re: locomotives and the culture around them but the track near my childhood home was the source of many adventures and “dares” from the late ’70’s to early ’90’s! Broke my heart when they shut the line down a few years back…

Thank you!

Thank you very much Doc. I can only say that I will miss Trackside Photographer and the adventures and experiences that landed in my inbox every week. Pretty well unique as an online community. Really glad you liked the piece.