Lost

Firmly ensconced in the suburban sprawl of Concord, NC, lay a railroad past bypassed with explosive growth in the Charlotte metropolitan region. As time has marched onward, the expansion of Concord has cloaked a past not unlike numerous cities and towns throughout the North Carolina Piedmont. Whereas the dependence on the railroad, whether it be for passenger travel or the corridor for a bygone textile industry, is gone, the stamp of the past remains conspicuous along this former Southern Railway main line. Modern day annals, however, tend to overlook Concord as compared to other locations along the route such as Salisbury, Spencer, and Kannapolis. Archival photographs of the railroad in Concord are few in number which has continued to trend as there are few contemporary photos taken here as compared to other locations.

The railroad origins of Concord date to the antebellum period a decade before the onset of the Civil War. In 1848, the North Carolina Legislature passed a bill for the construction of a railroad connecting the coastal region of the state with the interior Piedmont. The following year, the North Carolina Railroad (NCRR) was chartered with the intent of constructing a 223 mile corridor between Goldsboro and Charlotte. On July 11, 1852, a groundbreaking ceremony was held in Greensboro and construction of the railroad began. Four years later, towns along the route, including Concord, witnessed the passage of the first train to traverse the length of the railroad in January 1856.

After the tumultuous Civil War years, the Richmond & Danville Railroad (R&D) signed an operational lease with the NCRR in 1871. This lease remained in effect until the R&D was acquired by the Southern Railway in 1894. Maps of Concord during this era are in existence and indicate the exact location of the first depot. However, there appears to be no photographs or artist renditions in the public domain to reveal the early appearance of this structure.

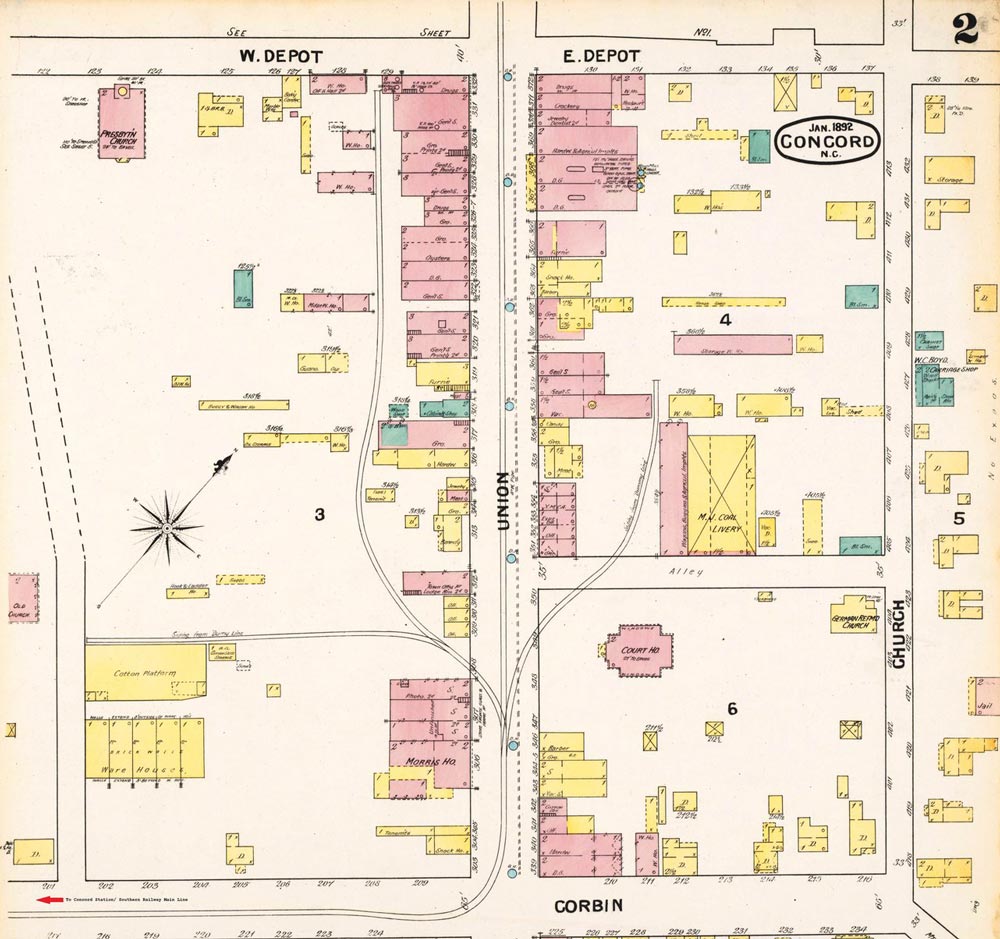

During the early 1890s, the Concord Railroad Company constructed a line from the depot area into the downtown district to serve the local businesses. Due to the topographical layout of Concord, the town is located on the heights above the railroad and the public sought improved efficiency for transport. Rather than walk or traverse these grades by horse and wagon, an inner city line was constructed to alleviate these concerns. Designed as a “steam” line and dubbed the “Dummy Line”, this street track diverged from the Richmond and Danville main line and ran on Corban Avenue until reaching the business district at Union Street. Here, it turned west and split numerous times with spurs to serve the local proprietors. Within a few years, it was extended further north on Union Street and to the Gibson Mills plant at present day McGill Avenue. In spite of these efforts, the “Dummy Line” was plagued with problems, most notably pertaining to reliability issues. Concord was among the first urban areas in the United States to utilize battery powered street cars and their usage on this route was generally unsuccessful. The battery life was short and passengers frequently assisted by pushing these cars. By the end of the century, the “Dummy Line” was history and Concord constructed a true streetcar system which partially utilized this former route.

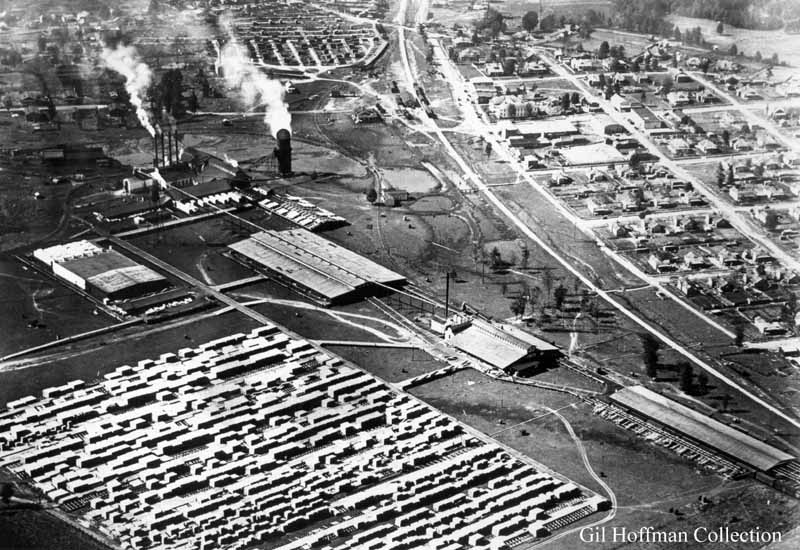

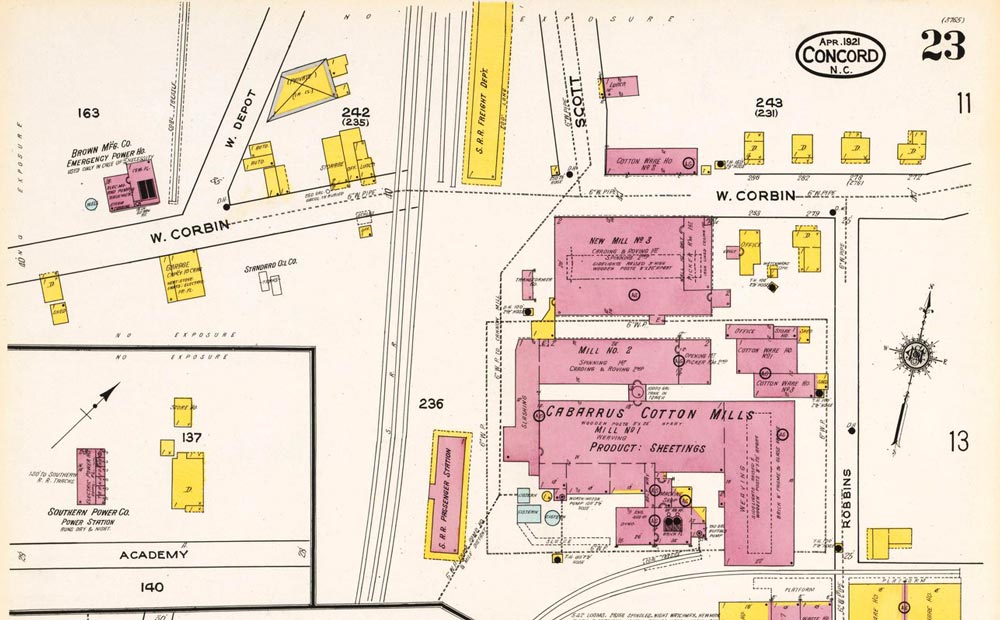

By 1892, a Sanborn Fire Insurance map indicates that a small wooden passenger station existed on the west side of the now Southern Railway main line opposite the freight depot and cotton platform on the east side. A separate smaller structure was located adjacent to it. Perhaps this was also the location for the original station as well—structurally repaired as needed but oddly located opposite the town district side of the railroad. It was also during this era that the Cabarrus Cotton Mills was constructed opposite the station on the same side of the tracks as the freight depot.

At the turn of the century, a new passenger station was constructed on the east side of the railroad by the Corban Avenue grade crossing south of the freight depot. This structure was also of wood construction and included a separate baggage office. The life span of this station was through the first decade of the 1900s until 1913. It was that year that a new passenger station would be constructed serving Concord until the 1970s.

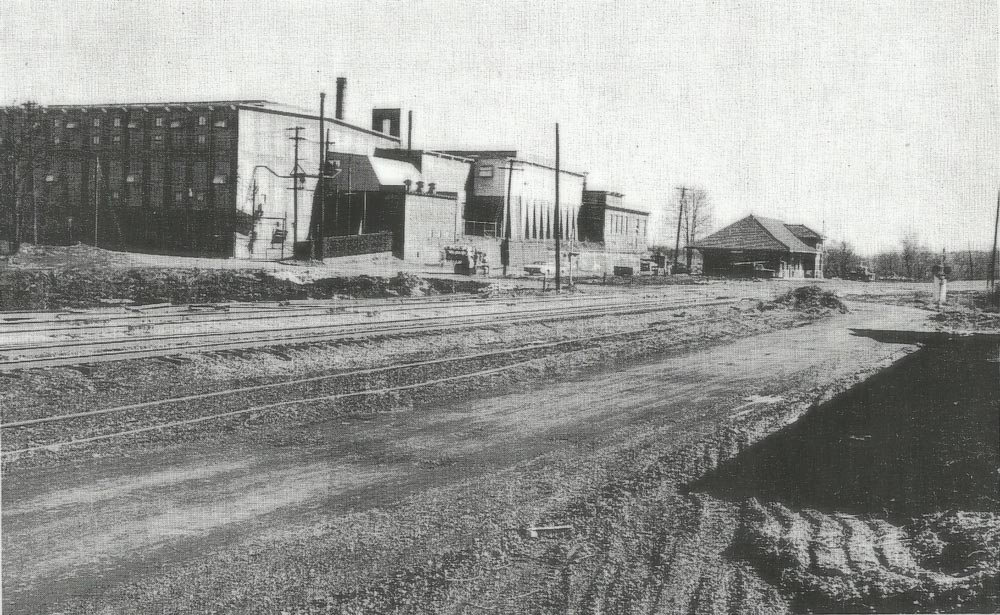

Construction began on the larger station several hundred feet south of the existing depot. The location, in effect, sandwiched the new site between the Southern Railway main line and the Cabarrus Cotton Mills. This new station, built with brick and trimmed in wood, was resplendent in the Victorian influence of the era. Solid and attractively designed, it became the railroad centerpiece for Concord during the halcyon years before the end of passenger service. The World War II years in Concord, as in countless other stations throughout the nation, proved a bright but brief zenith of the passenger train in full glory. As an example, in 1941, fourteen trains still called at Concord. Name trains such as the Piedmont Limited #33 and #34, the Peach Queen #29 and #30, and regionals such as #11 and #12, the Danville, VA – Greenville, SC, all stopped at Concord.

In the postwar years, as passengers left the rails in mass exodus, trains were either combined or abolished. Examples affecting the patronage at Concord included combining service from two trains into Southern’s flagship Crescent Limited. The southbound Aiken-Augusta Special was absorbed into the Crescent in 1956 and the northbound Peach Queen several years later in 1964. Further cutbacks would ensue as the passenger base eroded and services were discontinued. In 1971, what remained of the national passenger network was forged into Amtrak but the Southern Railway remained a stalwart by continuing to provide its own service that would continue through the 1970s.

In March of 1974, northbound manifest train 158 was passing through Concord when a defective wheel on a freight car picked a switch causing a derailment. This resulted in a pile up at the station area and the building sustained damage to its south and west sides. The damage was repaired but by this date, the venerable old structure was nearing the end of its useful life. In 1976, came the coup de grace. Trains #1, the southbound Southern Crescent, and #5 and #6, the Piedmont, remained on the timetable but by the end of the year, the Piedmont was abolished. With the discontinuance of the Piedmont, Concord was eliminated as a passenger stop. The Southern Crescent existed for another three years until the Southern Railway turned over its passenger operations to Amtrak.

On March 28, 1978, an epoch ended. The noble Concord passenger station, standing in silent vigil to a bygone era, met its end. Demolition began on this date and as the bricks crumbled, the visible connection to passenger rail at Concord belonged to history. It is, in a sense ironic, as a regional passenger rail renaissance occurred the following decade. In 1984, a joint effort by the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT)and AMTRAK resurrected the Piedmont train although it lasted but a year due to agreement conflicts. After a five year hiatus, service was resumed in 1990 and subsequently expanded in the 21st century. Today, eight passenger trains—the Crescent Limited and six Piedmonts— pass through Concord by the empty lot where its station once stood. With no structure to serve as a stop, Concord is now but a milepost location along the main line, nestled between the stops at Kannapolis and Charlotte. Whether a new station is constructed to restore Concord as a terminal may be a topic of future city discussion.”

Dan Robie – Photographs and text Copyright 2016

See more of Dan’s work at his website WVNC Rails.