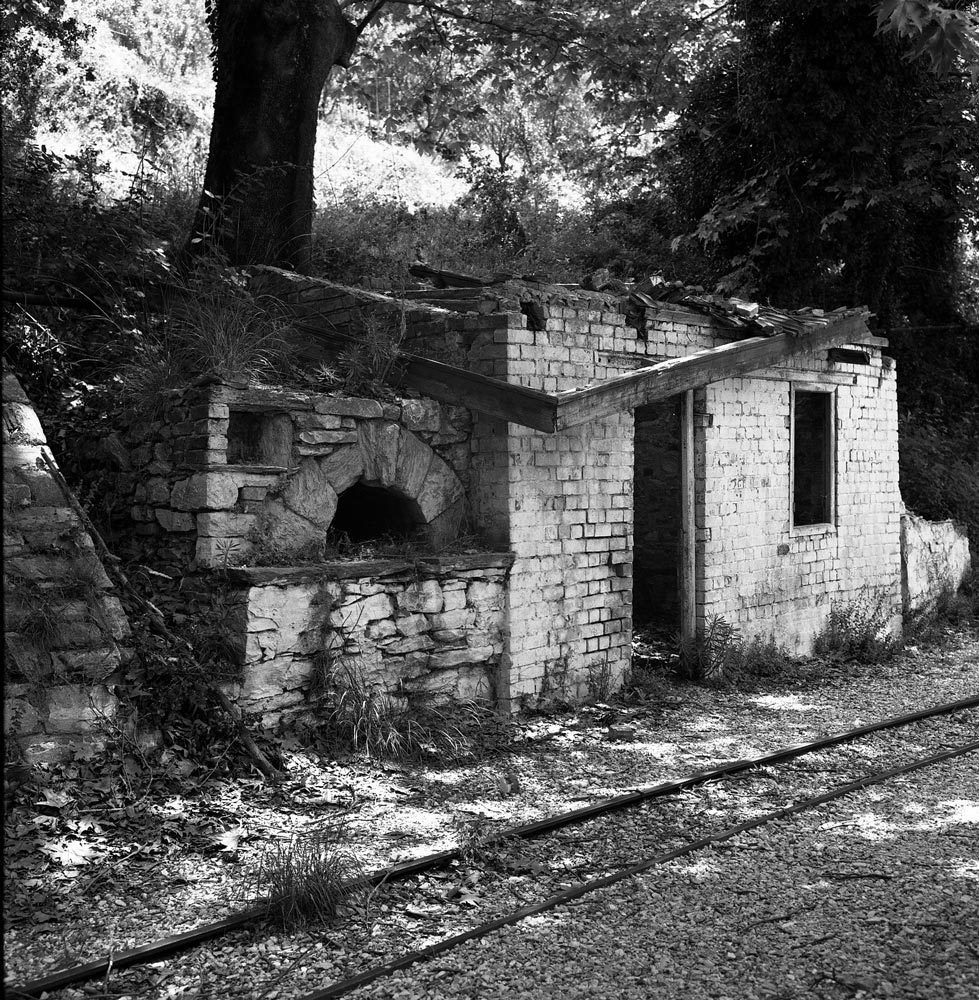

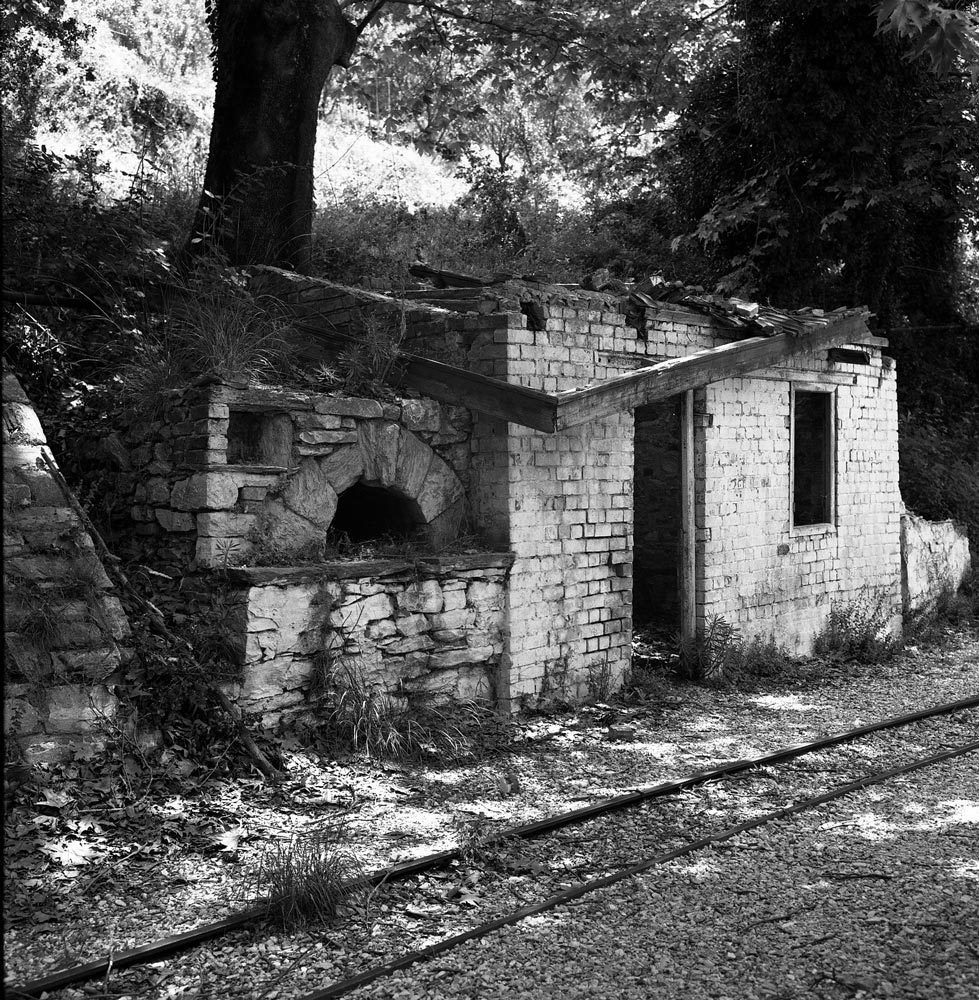

Deserted train station

Milies, Greece

The quiet village of Milies (Greek: Μηλιές) is the end station for the narrow gauge line that runs from the seaport of Volos into the interior of the Pelion Peninsula. Pelio is a rugged, mountainous region in east central Greece.

The lush mountainsides are draped with forests of beech, chestnut and plane trees, and the cherries, apples, and apricots are said to be the finest in Greece. Pelio was so rugged, it had little communication with the rest of Greece until the late 1800s. In winter, heavy snow makes roads impassible. During the centuries of Turkish occupation, the Greek villagers here were renowned freedom fighters.

Because access to the mountainous peninsula was so difficult, the goal of the railroad project was to improve transport and integrate the area into Greece’s economy. According to Wikipedia, “The 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) gauge 27 km line from Volos to Milies, a distance of 28 km, was constructed between 1903 and 1906 by the Italian engineer Evaristo De Chirico.” Service began in 1906. Construction was very difficult because of the need for six stone bridges, one iron bridge, many protective walls, tunnels, and aerial pedestrian bridges. The photograph above shows an example of the arch bridges, all built by hand by skilled rock masons.

When I took these photographs in 1994, the line was unused and the setting had a charming, sleepy, overgrown look to it. Service was discontinued in the 1970s, but may have been restored recently for steam locomotive tourist trains.

In the 1990s, there was a well-known bakery here where Athenians would buy bread before returning to the city (about a 5-hour drive to the south). The village ladies above had probably seen it all—strange tourists with tripods and cameras, and city-slickers with bags of fresh bread and cherries.

A Ride on the Piraeus, Athens, and Peloponnese Railway

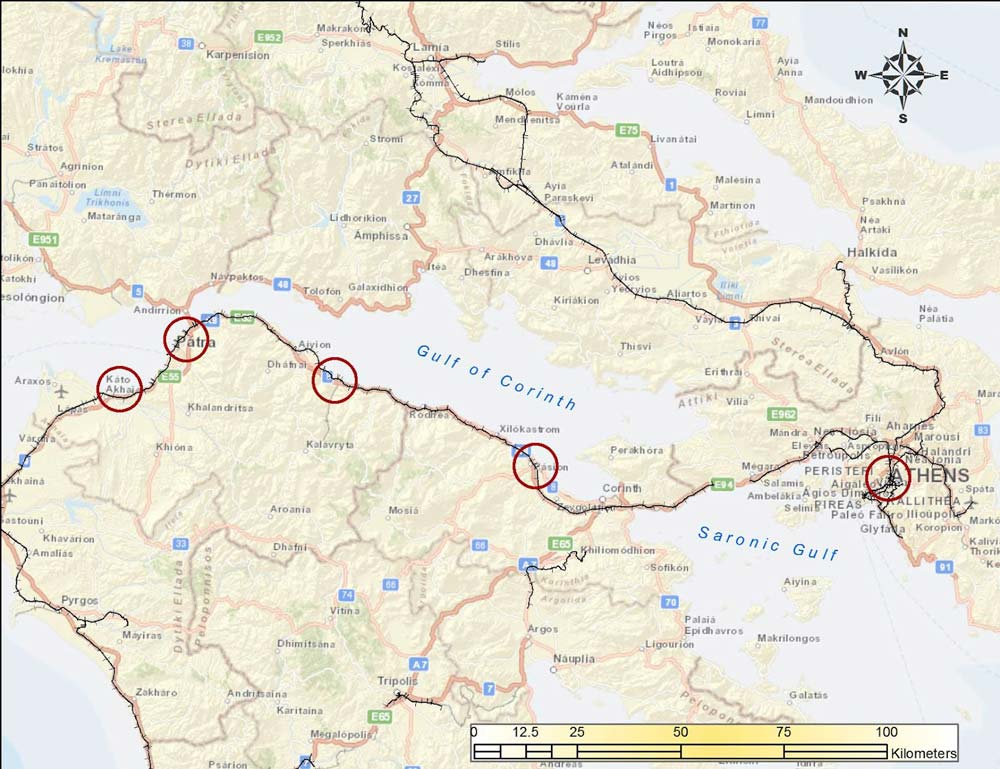

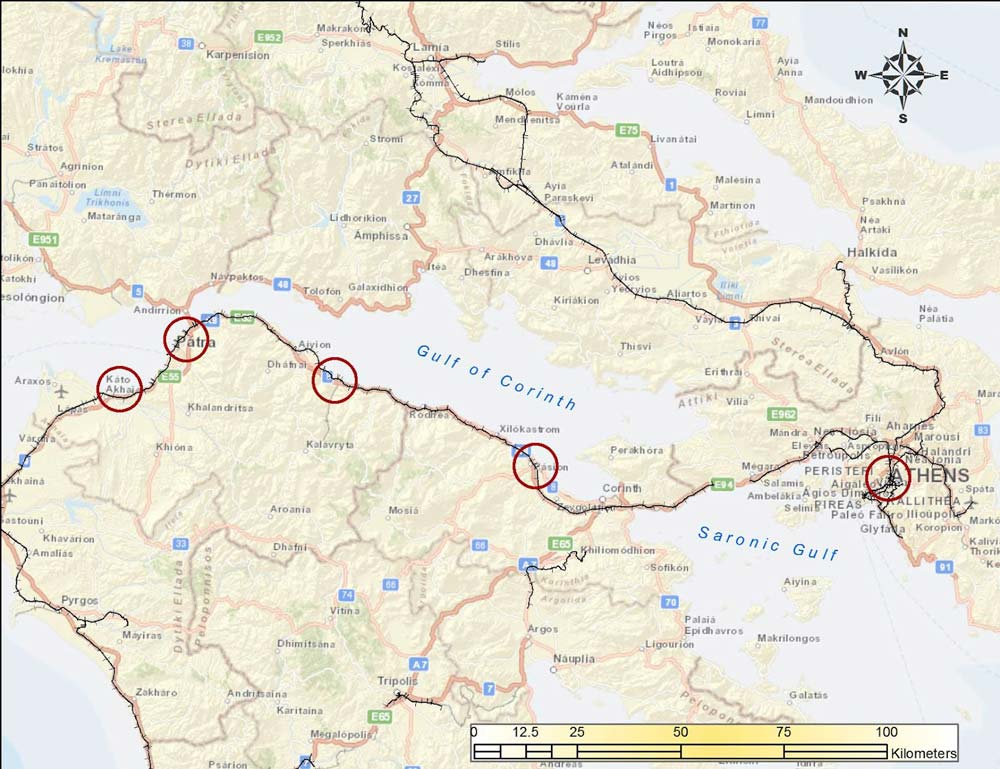

The Piraeus, Athens and Peloponnese Railway was a narrow gauge (1.00-meter) line that once connected small towns in the Peleponnese area of Greece with Athens. Our trip will carry us along the rails from the west end of the Gulf of Corinth to Athens.

The circles show locations of photographs. Background maps from ESRI Maps and Data.

This is the station at Kato Achaia, a farming community west of Patras. It has a sleepy land-that-time-forgot look to it. The water tank for steam locomotives still stands. As I recall, the train was delayed and we sat at a café for an hour or two.

As of 1997, the train consisted of modern but well-used diesel-electric rail cars. The windows were open and the train trundled along through vineyards and orange groves.

In Patras, we had to change trains for the main line to Athens. This was a busy station because tourists from Italy disembarked from ferry boats and many boarded the train here.

You see some refugees or gypsies on a bench. A historical note: After the Communist Bloc collapsed in 1989, thousands of Greeks from Bulgaria, Romania, and other countries were finally free to return home. Some had been stranded in the Soviet Union since the 1917 revolution. In Czarist Russia, Greeks were an important part of the merchant class and traveled throughout the vast land, but when the Bolsheviks imposed Communism, the Greeks were unable to leave. Many of their descendants spoke no Greek and had not been able to worship in Orthodox churches. After 1989, Gypsies (the Roma) also were able to travel across borders that had formerly been sealed. Finally, Albania, once a forbidden dictatorship every bit as secretive as North Korea is now, collapsed, opening the borders to thousands of impoverished Albanians who desperately wanted to find work in Greece. The people on the bench may be gypsies. These refugees have caused major disruptions to Greek society and its fragile economy.

This “Splendid” hotel was across the street from the Patras rail station. It was probably clean enough but noisy; I will pass.

The next major junction was Diakopto, where tourists could take the famous rack train up the gorge to Kalavrita.

Further east, the station at Narantza has not been used in decades. I used to vacation near here, and from my sister’s house we would hear the trains periodically rumble by. One engineer was distinctive because he tooted the horn more than other train drivers. Continuing east, the train would have stopped in the city of Korinthos.

Then the train crosses the narrow Corinth Canal (Διώρυγα της Κορίνθου), which connects the Gulf of Corinth (Korinthiakos Kolpos) with the Saronic Gulf (Saronikos Kolpos). The canal, dug in the 1890s, is narrow and mostly used by cruise boats.

Finally, after chugging through the industrial suburbs of west Athens, we reached the Peloponnese Railroad Station on Sidirodromon Street (built in 1889). It was pretty sleepy in 1997 and some men were sitting around playing backgammon and drinking coffee (Greek gents do a lot of this). I think the station is now unused and am not sure what its fate will be.

(This is Part 2 of a two part article on the Railways of Greece. Click here to read Part 1)

Andrew Morang – Photographs and text Copyright 2016

See more of Andrew’s work at his blog, Urban Decay.