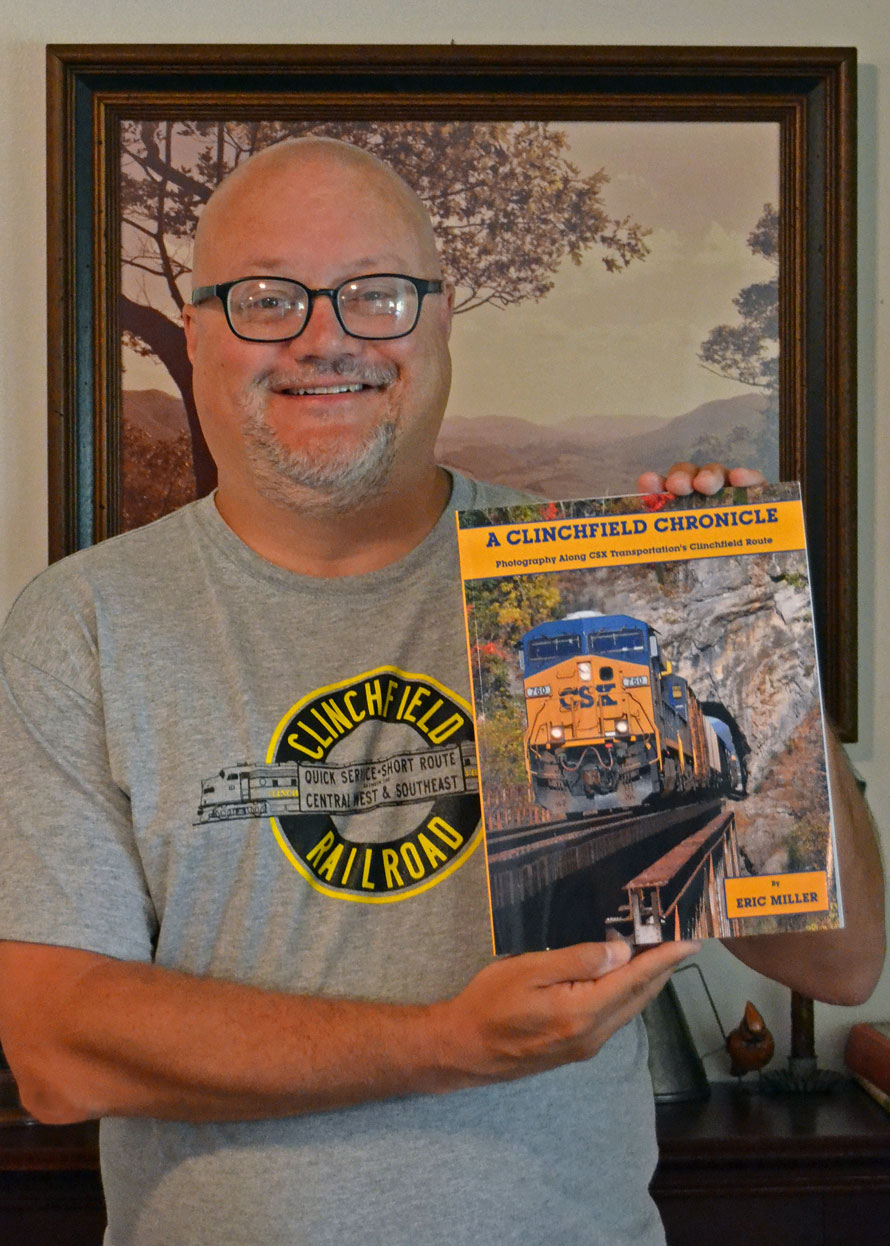

We recently had the opportunity to chat with Eric Miller about his lifelong interest in railroads and photography. Eric is a well known photographer whose work has appeared in numerous publications, including Railfan and Railroad, The Railroad Press, Railroads Illustrated, and Railroad Explorer magazines. His recent story on the Pocohontas subdivision was featured as the cover story in the March, 2017 edition of Railfan and Railroad Magazine. His first book “A Clinchfield Chronicle” was published in June and is available on Amazon.

Edd Fuller, Editor – The Trackside Photographer —Eric, first of all, thanks for taking the time to talk with us. Tell us how long you have been a railfan, and how did you get started? What is there about railroads that grabbed and held your attention?

Eric Miller – I have literally been a railfan all my life, and was born and raised (and still live) in the heart of the Appalachian coalfields. When I was a child, we still had the Louisville & Nashville, Clinchfield, Norfolk & Western, Chesapeake & Ohio, and Southern/Interstate operating as independent railroads, and I saw them all the time. We’d go out to dinner or shopping, you’d see L&N and N&W and Southern; they were almost omnipresent. Plus, most young boys (and girls) like trains when they’re little; I just never grew out of that fascination with trains. Helping cement that fascination was meeting Kenny Fannon, the greatest Southwest Virginia railfan without a camera, when I was four years old. Kenny’s love of trains is infectious, and his friendship only made my own love grow. Through Kenny I eventually met Ron Flanary, and through Ron, I met many of the railfan photographers that I call friends today.

Edd – Photography is a big part of your railfan activities. When did you first pick up a camera?

Eric – My dad momentarily let me use his venerable Pentax K-1000 to photograph a Southern/Interstate mine run in 1980. It’s an out-of-focus, blurry mess, but it’s my first railroad photograph. I actually began railroad photography in earnest in 1987, at the beginning of the true CSX era, and their ex-L&N Cumberland Valley Subdivision was my haunt.

Edd – Among railroad photographers past and present, who do you most admire? Who has influenced your own work, or provided inspiration?

Eric – When I first began, I was just making pictures of trains. I had no idea what constituted a “good” railroad photograph. I had some railroad books, but they were mass-market books intended for a non-railfan audience. Then, in 1989, I was given Steve King’s “Clinchfield Country” as a Christmas gift, and it was a revelation. Not only was it the first “serious” railfan photography book I ever owned, but it was the first book dealing with railroading right in my back yard. Talk about an eye opener. From then on, I insisted on books intended for railfans, new or old. I soon found that H. Reid and John Krause had visited my area back in the 40’s and 50’s, and they are no doubt the oldest influences on my own photography. Reid was a newspaperman, and brought a definite journalistic bent to his photography, and that influences me today – just cover what you see.

Of course, my closest railfan friend, Ron Flanary, is my biggest inspiration, and my mentor and muse. Ron first insisted that I upgrade to an SLR camera, and to switch from color negative film to color slides. I would also count Travis Dewitz (probably the best railfan photographer working today), Tom Nanos, and Robin Coombes as the biggest current influences on my work… What those guys are doing is just off the chart. I can only attempt to emulate them.

Edd – Are there photographers not normally associated with railroad subjects that inspire you?

Eric – In lots of ways, railroad photography is landscape photography, and I’m supposed to say Ansel Adams. For me, though, Adams’ work is too ethereal to be accessible. It stands beyond photography or art and you just have to stand in awe of it. Outside of railfan photographers, I’ve enjoyed studying the work of Sally Mann, who is best known probably for her portrait work, but she’s done some incredible landscapes, too. I’ve also been affected by the work of Shelby Lee Adams, an Appalachian photographer whose work also consists of a lot of portraiture, but also the environment and the scene. His work has really informed my own when it comes to “disappearing Appalachia.”

Edd – What three words best describe you as a railroad photographer?

Eric – Competent, diligent, unusual.

Edd – One of the things that I particularly enjoy about your work is that your photos, even when the train is the primary focus, give us plenty of context. There is always lots to see. What do you look for in scouting a location What makes a great railroad photograph for you?

Eric – Probably the single most important thing for me, when composing a railroad photograph, is to make sure the scene is distinctive. I call these “signature scenes,” spots that can’t be confused with anyplace else. (In contrast, I call the ¾-wedge made from a grade crossing “Anyplace, USA.”) I strive to make photographs that a knowledgeable observer can look at and immediately say, “Ah! That’s Elkhorn City on the Clinchfield,” or wherever. In an old, beloved article in Trains magazine, the author said, “Trains alone do not a railroad make,” and that’s so very true for me., which is why I try to include so much context. I also particularly enjoy juxtaposing trains, which are usually large and sensory assaulting, against a much bigger background. “The mountains are so big and my train is so small.”

Edd – How much time do you spend researching and planning a shoot? Or do you rely more on catching the moment as you explore?

Eric – There is actually a lot of planning and research involved in my photography. There are, of course, times when I just go out and make a train picture for the heck of it. But most of the time, there is an overarching goal in mind. I spent several years making a considerable effort to cover as much of CSX Transportation’s former Clinchfield as possible, with a list of “signature scenes” to photograph, and then making a concerted effort to capture those scenes. It was literally a matter of checking off items on a list. I similarly covered Norfolk Southern’s ex-N&W “Pokey.” I approach the articles that I’ve written and photographed for the railroad magazines the same way – with a checklist in mind of what scenes are needed to best illustrate the piece. I then work rather systematically toward making those photographs. And of course, there are always some “grab” shots along the way.

Edd – A photograph of yours that I really love is the “Bluestone Interiors” building with the blurred nose of a Norfolk-Southern locomotive just entering the frame from the right. It does not seem to me to be a “grab shot.” I picture you carefully framing this and then waiting for the train. Tell us a bit about how this photo came to be.

Eric – The location of the “Bluestone Interiors” shot is Bluefield, Virginia, a spot where the Norfolk and Western Pocahontas and Clinch Valley mains come together. It’s a pretty well-worn location as far as railroad photography goes, and that old Bluestone Interiors building has been incorporated into countless photographs over the years. I wanted to do something a bit different yet at the same time easily recognizable. I framed the shot as perpendicular to the Bluestone Interiors building as possible, and used the slowest shutter speed I could while still holding the camera by hand. I knew in advance that an unusual crop would be called for in the post processing, and you see the result.

Edd – In looking through your Flickr Photostream, I see that it is not all about railroads. When you are not shooting trains, what other subjects attract your camera?

Eric– I’ve always had an interest in landscape photography, which I attribute to my dad, who was an amateur photographer in the 1970’s and 80’s. Of course, being out along the railroad presents lots of opportunities for landscape photography, sometimes during the “down” time between trains, or other times when you’re enroute to a particular location. I also enjoy photographing “disappearing Appalachia,” the decline of the coal towns in which I grew up, and I like shooting old barns, for their uniqueness and the textures that they offer in closeup.

Edd – Your Flickr photos are predominately color, but there are some black and white as well. How do you determine that a scene should be presented in B&W? Do you make this decision as you are shooting, or do you decide during post processing?

Eric – I shot some black and white back when I was shooting film in the early 90’s, for two reasons: one, to try something different, and two, as part of a photography course that I took when I was a senior in college, to satisfy my degree’s “art” requirement. Today, I shoot everything in color, with the intention of presenting the finished photograph in color. Sometimes, though, it just doesn’t work out that way. Converting a photo to black and white is always something I agonize over, and not a decision I make lightly. It is usually a matter of the lighting conditions at the time of the photograph that will push me to make a final black and white conversion. I have a great disdain for converting photographs of steam locomotives into black and white and then saying it’s “classic.” To me, such efforts are hokey and contrived. If you see a black and white photo from me, it’s because the original color version just didn’t work to my satisfaction.

Edd – Tell us about one of your favorite photographs. What makes this shot meaningful to you? Is there a backstory ?

Eric – One of my very favorites is, amongst all the photographs I’ve ever made, a rather unremarkable one, I suppose. It’s of CSX Extra 99 South, a loaded southbound coal train, very slowly grinding its way out of Towers Tunnel, deep in the Breaks canyon on the Clinchfield. There’s a reverse curve in the foreground, and a big belch of black smoke as the lead units clear their throats after the slow slog through the tunnel. There’s still a lot of snails pace climb to go for that train as it heads toward the summit of the Clinchfield at Sandy Ridge Tunnel. I’d spent the day in the Breaks and this was one of the last trains of the day, and one of the most dramatic in terms of the experience. That photo, for me, sums up my experiences on the Clinchfield, and really defines what railfanning on the Clinchfield was like.

Edd – What projects are in your future? Do you have a dream project?

Eric – As usual, I’m working on some magazine articles, one of which is finished and two others which are in various stages of completion. I also have at least two more book projects in mind, one of which would be my “dream” project, a coffee table book that transcends the railfan audience.

Edd – If you could go anywhere in the world to photograph railroads, where would you go? If you could return to a place, where would it be?

Eric – I’ve always been interested in the railroads of Australia and New Zealand, and would love to go “down under” for a month or so of railroad photography. I was in Colorado in the summer of 1989, but with an amateur camera, and I might like to go back there now, with better equipment and more experience, even though the Grande is gone and the BN subsumed into BNSF.

Edd – You recently published a book titled “A Clinchfield Chronicle.” Tell us how that project came about, and how you became interested in the Clinchfield.

Eric– The Beatles once sang, “The Long and Winding Road,” and that’s apropos for this first book. I’d been asked by lots of folks when I was going to do a book, and I’d always answer, “Well, someday.” When someday finally seemed to roll around, the book was originally going to be a collection of my railroad photographs and railroad-related poetry. I started on it, but it rather quickly fell to the wayside with work and other hobby obligations (mostly magazine articles).

As I mentioned earlier, the Clinchfield was one of those railroads that I grew up with, and many of my pre-camera railfan experiences were along that storied route. When I began my “career” as a railroad photographer, the Clinchfield was always a regular stomping ground for me. After CSX closed the Clinchfield as a through-route in October 2015, I turned my thoughts to a retrospective of my photography on the CRR. Originally, I was going to include ALL of my Clinchfield photography, including the film work, but then decided that it might be best to just showcase the digital photos, and to limit the time frame to 2006-2016.

Edd – New technology and consolidations have made for rapid changes in the railroad industry. What elements of the railroad landscape that have disappeared do you miss most? What subjects do you wish you had photographed more while you had the opportunity?

Eric – Aside from the disappearance of the railroad companies that I came to love from the very beginning, I think I’ve most been affected by the loss of the caboose in the early 1990’s, and the more recent falling of the Norfolk & Western’s distinctive color position light signals. I detailed some of these changes in my “In Remembrance” piece that I did for The Trackside Photographer a few months ago, but losing cabooses and the CPL’s has hit me hardest. I am a sentimentalist at heart, and I long for the “way it was” when I first started in this hobby, when I was a child. As for regrets, there’s lots of things I wish I had photographed more of when I had the chance—the CPL signals on my hometown N&W Clinch Valley District, mine runs on now-gone Interstate Railroad branch-lines, and most of all, the men and women that worked on the railroad, people that were dear friends to me, some of whom are retired, and many of whom have passed.

Edd – Do you have any stories about a day trackside that went completely wrong, or wonderfully and unexpectedly right?

Eric – That’s the story of any railfan’s life, isn’t it? Even on the busiest lines, you can get totally “skunked.” I immediately think of a day that we spent on Norfolk Southern’s “Pokey” main in McDowell County, West Virginia; normally this route would be good for at least ten trains, and that would be a “bad” day. It was one of those late spring days that’s more like the height of summer… Hot and sticky humid, but we didn’t mind, because we’d see a bunch of trains. Instead, what we got was TWO trains, and one of which was a work train that wasn’t moving. And I can’t count the number of days that have been near-busts on Norfolk Southern’s Bristol to Radford, VA Pulaski District.

You temper those bad days with the good ones, and there’ve been lots of those, too. Days when we were expecting, by design, to only see two or three trains and we’ve ended up seeing 15. Or getting totally and completely surprised by the appearance of a Norfolk Southern heritage unit leading an empty coal train. Trains showing up at the precise moment when the lighting is just perfect. It can be feast or famine out there, and you learn two things quickly: be patient, and take the good with the bad.

Edd – You are mentoring you son, Tristan, in rail lore and photography and he has recently had some success at getting published. You must be proud. What is the most important piece advice that you have given Tristan in his pursuit of railroads and photography?

Eric – Tristan didn’t stand a chance not liking trains, growing up in a house full of railroad photographs and books, and being exposed to trains all the time. However, his mother and I have not “forced” him to continue his interest; it’s been purely his decision to become a railroad photographer. If he’d have grown out of it and wanted to take up fishing or watercolor painting, that would have been fine with us, and we’d have supported him in the fullest. So, of course, I’m bursting with pride that he’s becoming a darned good railroad photographer; in many ways, I’m now just the chauffeur, driving him to wherever he wants to go do some photography. Besides some technical advice, both in-camera and in editing/processing, I think the most important thing I’ve imparted to him is, like I said in the last question, be patient. Work hard, and be patient. Learn from your mistakes. Every time you snap that shutter is not going to result in a perfect photograph. You don’t get the shot today, go back and try again. The train didn’t show up when you needed it to? It will, just some other day. Take the good with the bad.

Edd – Words to live by. Tristan is lucky to have you for a dad.

Of course, I have to ask about gear for the benefit of all us camera geeks. What is in your camera bag on a typical day as you set out to photograph trackside?

Eric – I literally laughed out loud (LOL, as the youngsters would say) at this question. I currently have a nearly worn-out Nikon D90 that I’ve used since I bought it new in 2009. It’s well past time to replace it, and it’s becoming rather cantankerous to use, particularly in the low-light conditions that I enjoy. I have for many years used only two lenses, and there’s only two in my camera bag now, a Nikon 18-110 and a Tamron 70-300. I have found through 30 years of railroad photography that these two are really all I need.

Edd – It is refreshing to hear that you are out there taking great photographs without obsessing over the latest equipment. Do you have a favorite “go-to” piece of camera gear. What non-photo gear do you consider essential when you are trackside?

Eric – I use my Nikon 18-110 lens quite a bit, as it allows me to first and foremost closely replicate what the human eye “sees” as it looks at a scene, and you’ll often find me in that 35 to 50 mm range. That particular lens also offers the opportunity to go wide when I need to, as well as a little bit of zoom. That lens is the one that’s always attached to my camera when it’s between shots, or when I’ve put it away.

My earliest railfan photography experiences were made up of literally just going trackside and waiting to see if something showed up. I quickly learned to read signal indications, and would stop in to railroad yard offices to ask if something was running. Around 1992, I was given my first radio scanner as a gift, and I can’t really imagine railfanning without one.

Edd – So much of our photographic output ends up on-line these days. Do you print your work? Do you sell prints or participate in gallery shows or other “off-line” venues?

Eric – I have typically only done prints for hanging in my own home, or for friends, when they’ve asked for one, or as a gift. I have done some prints and donated them to local nonprofits for sale in fundraisers or silent auctions. So far, there has yet to be an Eric Miller gallery show.

Edd – Certainly, the entire field of railroad photography has changed in the past twenty-five or so years. Has digital technology and social media changed the way you work?

Eric – Absolutely! I come from a film background, and I used Kodachrome 64 for many years. Kodachrome 64 wasn’t known for its latitude nor its forgiveness of exposure errors. Plus, it was pretty expensive for someone my age at the time. So, conservation was key. I had to make every shot count, and I didn’t do too much experimenting. Digital photography changed all that, and changed it for the better. As long as you’ve got space on your memory card, you can burn all the pixels you want, and be as creative as you want… If it didn’t work, just delete it and move on. Digital has opened up the opportunity for a whole world of creativity and experimentation that I didn’t have when I was shooting film.

I’ve never belonged to any of the online groups like Trainorders, but I have gotten lots of “heads ups” about special movements or unique locomotives nearby through Facebook. I run a group on Facebook, the Southwest Virginia Railfan Association, and the members are really good about posting train sightings and updates, and that has taken out some of the uncertainty about being trackside.

Edd – And one last question. We all tend to change and grow creatively over time. What future directions do you see for your work? What new paths would you like to follow?

Eric – I’ve become known for making “bad weather” photographs, particularly on cloudy days. There was a time when if the sun wasn’t going to be completely dominant of the sky, I wouldn’t even think about making a railroad photo. I’ve grown past that; trains run in any weather, and some shots that I need to get can only be done, due to lighting angles, on overcast days. I also like pushing the limits of my camera in low-light situations, and intend to continue doing so after I get a new camera, which will be soon. I have some more lines in mind that I intend to cover photographically as comprehensively as I’ve done the Clinchfield and the Pokey. I have an entire project in mind that is part railroad, part “not” railroad, and it will be done exclusively in what most would consider poor lighting conditions, and hopefully, if it works out, exclusively in bad weather.

Technology moves so fast these days, and I sometimes struggle to keep up. However, I don’t see myself with an ATCS-equipped laptop, nor a drone. For the foreseeable future, I see me as I have been, a camera and a scanner, documenting whatever comes down the track.

Edd – Eric, thanks so much for taking the time to talk about your work with us. I, along with many others, look forward to seeing where your railroad journey takes you.

Eric – I appreciate the opportunity to have discussed my photography with you, and welcome the kind words and well wishes. I particularly thank The Trackside Photographer for featuring some of my writing and photography.

Photos and Text Copyright 2017 by Eric Miller