All in a Night’s Work

Dispatcher On The Radio: “Mr. MacDermot, AB2 had to set off a unit last night account a slipped pinion. It’s on the siding near the signal on the west side of Richmondville hill; could you arrange to get someone out there to cut the pinion off so we can move the unit?” (“Slipped pinion” is railroad lingo for a locked axle, usually.)

“What’s the unit number and did they say what axle has the slipped pinion?”

“It’s one of them ex-Detroit Edison 6-axle EMD SD40’s; I think he said it’s number three pair of wheels that were locking up.”

“OK, I’ll see if I can get someone from Oneonta to meet me out there – might have to get a track department person to slide a tie out to make room to drop the gear case.” Dispatcher Over-And-Out

I called Oneonta; the Diesel Track already knew of the problem. “We’re going to have an electrician head out and meet you there.” That seemed odd to me; would an electrician be equipped to drop a gearcase and cut off a traction motor pinion? Sounded more like a job for the road truck to me, but “ours is not to reason why.” Lets see what we’ve got first.

Why Cut A Pinion?

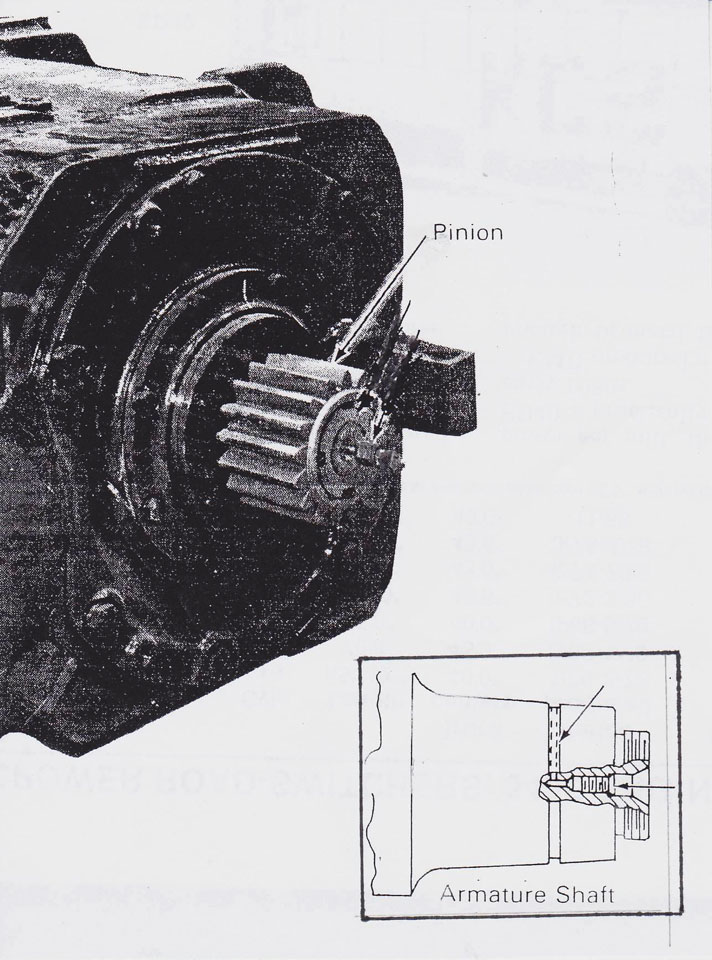

On a locomotive, when mechanical failure causes one pair of wheels to lock up, there is really no alternative but to make repairs “in situ”; the unit is essentially immovable. You hope the crew was able to nurse it into a siding; if not, repairs will have to be done wherever it stopped, on the main included. A seized motor armature, a slipped pinion or a failed journal bearing are the three possibilities. It can be one nasty job!

I arrived thirty minutes or so ahead of the electrician; the unit was running so I test-ran it back and forth an engine length to see what would happen. It didn’t want to go forward but seemed to move normally in reverse. I checked underneath; no damage was evident; we might have enough height to drop the gear case, or the track department might have to be summoned to remove a tie. My Oneonta electrician rolled in, and at the same time, a threatening black cloud opened up, accompanied with lightning, thunder and torrential rain.

“Get up in the cab and let’s wait this out; if you try to work underneath right now you’ll either drown or get electrocuted.”

We sat in the cab and chatted; the skies had opened up and by now there was an inch of water under the unit – remember, we were on a little used siding, overgrown with grass, not the main.

Electrician: “I’ll have to wait a while until that dries up; I’m not laying in that mud trying to cut no pinion.”

I had the doors to the high voltage locker open looking things over, so I asked my electrician, “make sure the independent brake is set and take throttle notch one in reverse so I can see what is going on here.” Things looked OK.

“Try that for me in Forward.”

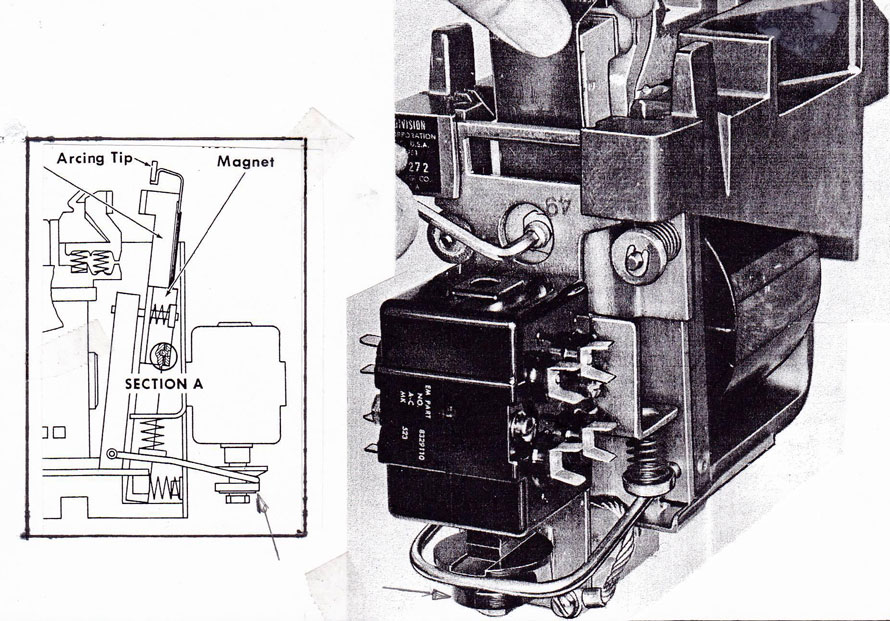

The correct contactors were not closing for forward motoring. What was happening, other than that it was still pouring rain?

I peered into the locker, repeating the tests until daylight finally dawned: a bobbin was missing under the interlock block on one contactor. So the motor they thought had a slipped pinion was trying to go the opposite direction to the other five motors, making it appear one pair of wheels was locking up.

“Don’t bother unloading your tools, you won’t have to cut a pinion today.”

There is an old joke about the guy who had to change a flat tire, but while he was away getting it patched, squirrels stole all five lug nuts. As he dejectedly sat by his car figuring he was really stranded now, a forth grader walking home from school stopped to see what was wrong. Hearing his story, the fourth grader promptly told him, “All you have to do is borrow one nut off each of the other wheels; three nuts will be good enough to get you home.”

My subconscious mind must have remembered this because as I studied the high voltage cabinet and its array of switchgear, it occurred to me a couple of dynamic braking contactors were sitting there with perfectly good bobbins; dynamic brake contactors don’t need to be picked up in motoring.

I asked my electrician, “Why can’t we just steal a bobbin off a braking contactor and replace our broken one? We can tag the unit “Dynamic brake inoperative, do not use”, then when they pick it up, it can go right in consist and they can put it to work.”

My electrician didn’t have suitable tools, but I did, so I changed the bobbin, moved the unit an engine length in each direction to make sure it was OK and told the electrician, “We’re done – you can go home”. When he got back to Oneonta, he could have his foreman call the dispatcher and tell him he could pick up and use the unit.

Epilogue

A few months later I was working in Binghamton shop when shop manager Jim Ratchford asked me if I could come upstairs – the local chairman of the electricians was griping about some grievance he claimed I knew about. I joined the meeting – “So what’s the problem?”

“Well the Oneonta electrician says you were working on a locomotive and that he can prove it; he wants to get paid a call”. (A “call” typically would be some number of hours agreed to in the contract, a half shift for example.)

“Did he explain the circumstances?” (I’m not happy; in fact I’m pissed, if you will excuse the language.) I explained the circumstances, clearly, for the benefit of all present.

Local Chairman, looking a bit uncomfortable: “Well he thinks he’s entitled to a claim, Mr. MacDermot agrees he was working on the unit.”

Me: “Jim, the company saved this locomotive a trip to Colonie Diesel Shop for a combo change (a combo is a new traction motor-wheelset assembly; the locomotive has to be spotted on the drop-table, the bad order assembly removed and a new combo raised into position, cables and brake rigging re-connected), plus at least a week of out-of-service time, not to mention saving your electrician from a tough job under hazardous conditions. So, if this man feels he really deserves it, I definitely think we can justify paying his claim. And wish him a nice day from me.”

C.G. MacDermot – Copyright 2017