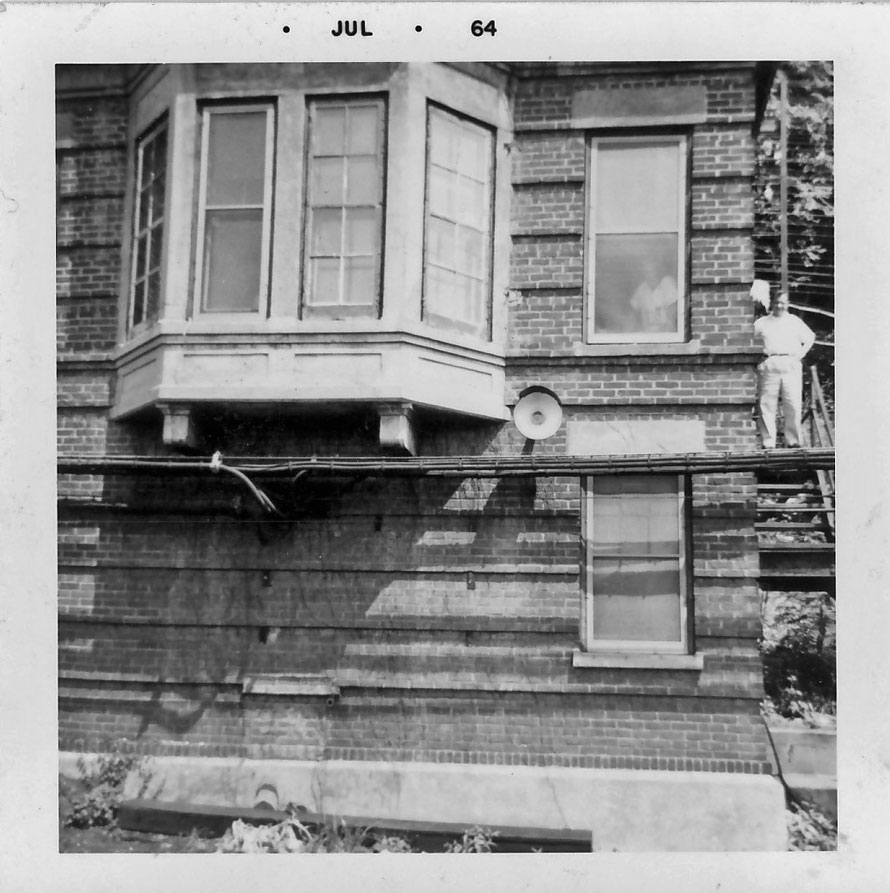

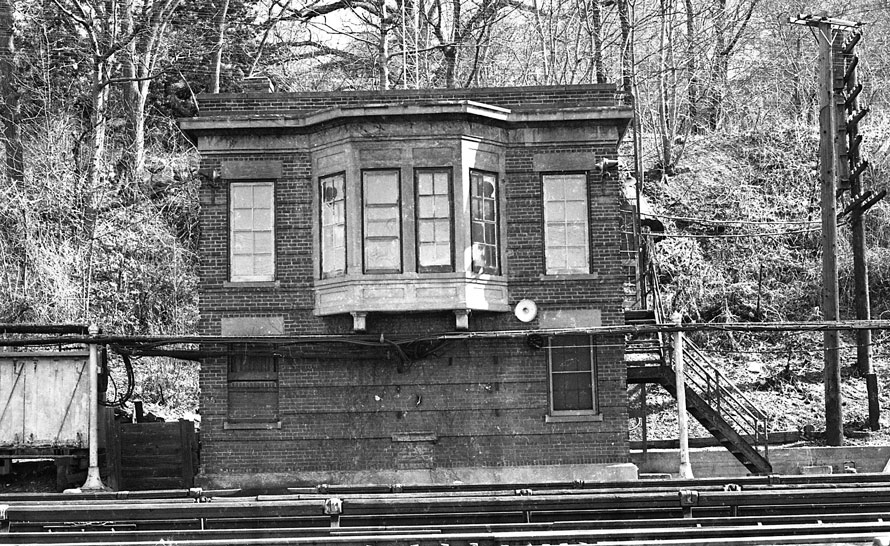

During the mid-nineteen-sixties, my father’s assignment was changed around. He would open OW tower, located almost in the shadow of the Tappan Zee Bridge on New York Central’s Electric Division, on Monday mornings. OW was closed from Saturday afternoon until he got there.

I recall that we got up in the dark, because he had to be there at 7 a.m. My dad was not a morning person, and so we did not talk much on our drive to the tower, even though I was always excited to be with him going to work. We had to park and walk a bit to the tower, and if I went with him during winter while I was on vacation from school, he would always grumble about how we had to drive into a lumber yard that had not been plowed and then push our way to the tower along a path that had not been cleared. When we got to the tower and climbed up the two flights of stairs, he would, after I pestered him, let me take out his NYC switch key to open the padlock.

OW had a coal furnace, and sometime Sunday night someone, I never knew who, came and fired up that furnace so the tower would be warm for us. In winter you always left the faucet in the tower sinks drip, otherwise the water lines that came from the passenger station in exposed pipes would freeze up. My father never let me put coal in the furnace in case something bad happened; he would put it in when we got there. The signal maintainers took care of it after that.

My position during the morning rush hour was to sit and watch trains go by, and my father would let me pull and push the levers sometimes, as he always said it was easier for him to do it than to call the moves. Since I did not get to this tower with him often, I never learned the machine as I did at JO and NW. After the morning rush he would call the moves and watch and make sure I pulled the correct levers. Since I learned how to read the boards in other towers I was able to do that at any tower and after a bit it would come to you.

One move that I always wanted to do was to cross the trains at Philips Manor from Track 4 to Track 2. That move was very different, because it was far away and the levers for the move were on the OW machine. I believe at one time there was a tower at Philips Manor, but when we went there the switches and signals were controlled from OW.

In those days, as you know, we had named trains with observation cars on the rear, and my father always told me when the 20th Century Limited was coming. If you plugged the Century for any reason, it had to be good! So No. 26 would go by, and I would watch for the observation car with the blue and white sign on the rear. There was one other train with an observation car that went by on his shift also.

I’d see the jobs coming east from Poughkeepsie towed by electrics as well as the crack trains. Freights ran mostly at night, but as a rule one would go by going east while we were there. I believe it was NY-2 or NY-4. I would count the cars, and in those days the conductor or rear brakeman would come out of the back and you’d give him a wave and he would return it. There were different hand signals you would give if something was wrong. I remember my dad said was if you pinched your nose and pointed down to the ground it meant the train had a hot box.

After the morning rush hour my dad would get a call, and it would be one of the Harmon traveling switchers that he would put into the Chevrolet Plant. As a rule, one of them would come out of the plant and bring cars down to the siding at the tower for the westbound freight to pick up at night. Sometimes the conductor on the job would drop off at the tower and come up. On one of those days he asked my dad if it was OK to take me for a ride on the engine while they made the move. Of course he said OK, and out the door I went. That was my first freight train ride, and I never forgot it. When I hired out in 1970 there were five traveling switchers coming out of Croton East. Four of them, as I remember, came to Tarrytown to keep the Chevrolet Plant switched out, and he would place cars east of OW for pickup at night, or bring cars back to Croton Yard.

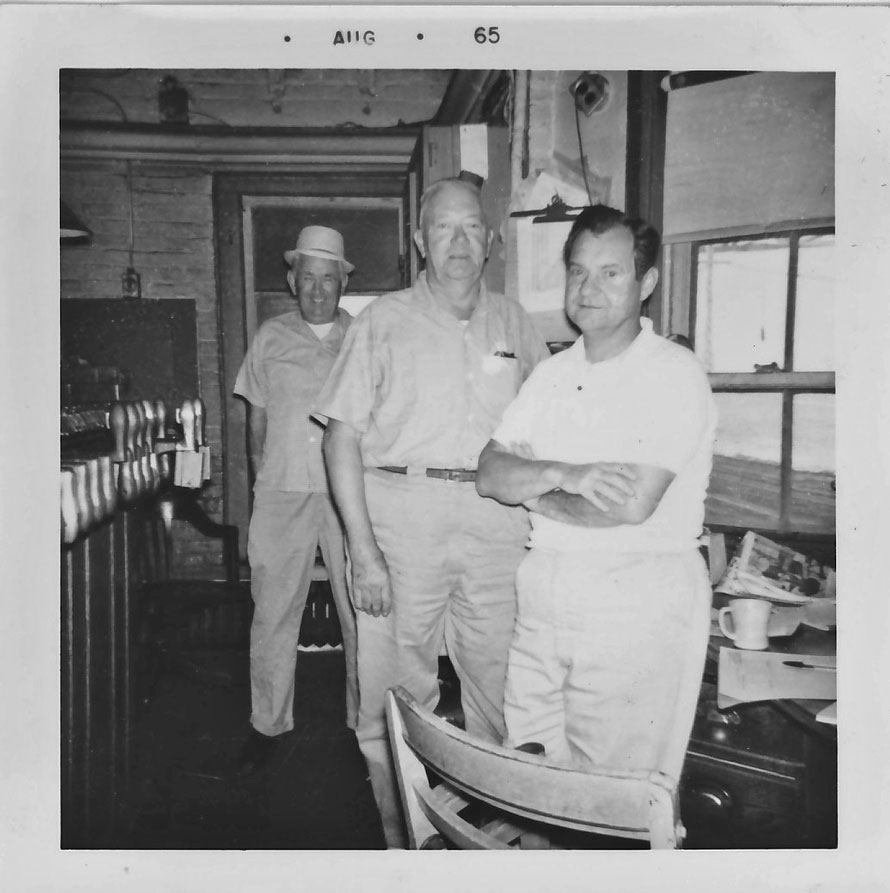

Some people I never see written about are the signal maintainers. Without them and all they did, nothing would work right at any interlocking. Today those men are called the C&S Department in many places, but the job they do is the same—putting oil and graphite on switches, checking switch heaters, signals, and in those days, cleaning the lever machine. Today, with computers and a mouse, there is no machine in a tower to keep clean and oiled. But the job they do is just as important because when a dispatcher says he can’t get a switch, or the circuit drops out and he can’t clear a signal, those are the people who fix the problem. Joe Hard and Fred Gunther were the maintainers at OW. Since the GM plant was such a big customer, I suspect that is why the railroad had two of them on duty. They were very happy-go-lucky guys, and I expect this was because they were very close to retirement when I met them.

In the photo of my father at his desk you can see a black box in front of him. They had an approach bell for all four tracks so the operator knew a train was coming and could clear up for them. On the left side of the desk was the horn where you could hear the dispatcher and other towers talking. In front of that is the mouthpiece he spoke into to give the OS for all trains and to answer any questions the dispatcher might have for him. On his right were two phones—one a regular land line and the other a direct phone to the GM plant so the crews working there could speak to him directly and vice versa.

There was also a block phone for the call boxes along the tracks. In those days a crew member who had a problem would open that big box carefully. The reason for the care was that bees made nests in them. When he knew the box was OK he would crank the handle on the phone. They had a list in the box of how many cranks for what tower or station you were trying to reach. In those days the only trains with radios were the long-haul freights.

Every tower had a clipboard or something like it to post the bulletins on pertaining to special instructions that were not in the timetable. Things like track work and temporary slowdowns were covered on these bulletins. The big clock you see in front of my father had several large batteries in it, and each day at 11 a.m. the dispatcher would give a time check. Some of them would say “11 o’clock” about three times then say “now,” and the operator would push a button to set the clock so it was exact. The second shift people did the same thing at 7 p.m. When all was quiet you did hear the clock tick.

My father carried a personal AM radio with him to have a little back ground music. Without that, those eight hours went by very slowly when you were not busy. But for me it all went by too quickly, and there is nothing I would not do to bring those wonderful days with my father back. I hope you enjoyed reading this. Because my dad often took me with him, I had a great childhood. Now I enjoy sharing stories of what it was like.

John Springer – Photographs and text Copyright 2020

This story first appeared in the New York Central Historical Society's Magazine, Central Headlight.

What a great piece – so glad that all those photos and memories are shared – a true segment of rail history!

Thank you Jim, I was a very lucky kid to have the father I had.

Thanks for a very interesting article. How were the switches controlled during the weekend closing from Saturday afternoon until 7:00 AM Monday?

Bill the switches were all lined straight, the signals put in. Nothing crossed over or went to the Chevy plant till Monday morning.

Thanks!

You’re welcome Fred

Thank you for sharing this… such great memories!

Your welcome

Great story and good photos. It’s great that you record stuff like this, these are the stories that few are bothering to record!

Lee, my dad never could understand why I took those pictures:-) when I started writing these stories just before he died and he saw that people enjoyed them he smiled!

Those were the days when non-employees could be on the property. As litigation increases access by family members decreases. When sons visited parents they could be helpful, my experience was that my preteen son was a more valuable worker than some of the employees; he was intelligent, motivated and listened. I’m sure the description suits John Springer.

The happy go lucky guys were probably typical of many employees in the northeast. As an railroad employee with the Reading and Southern I noticed an attitudinal difference in the different regions. Both had warm friendships but happy go lucky was definitely not a southern thing.

I sometimes took my visiting father with me during track inspections. He wasn’t asked to contribute much to the work but was pleased to learn things about railroading that his train engineer father never imparted. I imagine it proved useful when socializing with several of his in-laws who were railroaders.

Robert,

Thank you for the kind words. Yes today things are much different, not for the better either. I lost a very dear friend a few months ago he was a track foreman.and while he was sick I met a group of trackmen who stuck by him, right to the end. Because I was an engineer i never got to meet many of these guys and I must tell you I’m sorry I didn’t. They are a very close group and today when they get together every couple of months they include me along with my friends brother and we swap stories. Several times my father got caught with me in the tower each time the boss who was there said the same thing. They asked if I was his son and would smile at me and tell him I’m going to make a good railroad man. Yes things were very different then.

You’re a lucky man to have such terrific memories.

I really am John and I know it, what I would not do to have another day in the tower with my dad now. But I know I had. Any good years and later on when he retired I took him with me we had a great life together and I miss him a great deal.

Wonderful, Wonderful, Wonderful! Thank you so much for sharing!

Thanks Ed

What a great story, loved hearing the operational details. Wonderful father son and railroading memories you’ve enjoyed. Thank you for sharing!

Thank you Glenn.

That is a wonderfully written story with great photographs.

Thank you Paul glad you enjoyed it.

Absolutely wonderful, as always, John; thank you so much for sharing these memories. That square snapshot of the three men in the tower brought me up a little short when I read the date: Aug 65, the very month of my birth. My own experiences on the Electric Division do not go nearly as deep as yours — my father did not work for the railroad — but we did get to spend some time inside DV Tower at Spuyten Duyvil, making friends with Mickey Shapp, the towerman, in the later 1960s and early ’70s, and we made the acquaintance of the signal maintainers, Eddie Kemple and Rudy (whose last name I can never remember). These two railroaders had hired on during World War II, so they had seen a LOT by 1980; woe that I never wrote any of their stories down, or even took a photo of them . . . but joy that you, John, can bring me just a little closer to those glorious childhood days. Keep the stories coming!

Oren,

So glad this brought back some good memories for you. I knew Rudy! I met him at North White! He had a brass whistle he had on his key ring I use to take it and go outside the tower and blow it, one day he gave it to me. I think of it often but never could remember what happened to it. I guess I lost it. He was a really nice guy.

Rudy Frank

That’s right! Bill did you work with him? Real nice guy

Another brilliant piece John ….. WELL DONE

Thank you glad you enjoyed it.

My Dad & I both love reading the stories about you and your Dad! Keep up the good work!

Thanks Danny, good to see you last week in Springfield

Wonderful memories you have, John. Thank you for sharing them with us. Seeing the date stamp on some of your photos really brings back wonderful reminders of the what seems today as a less congested life back in the ’60s.

Yes Russell the 60’s were a great time for me! Glad you enjoyed it and it brought back good memories for you

A nice testimonial to your dad and to railroaders of the past. I knew your dad when I worked in the signal dept. and electric zone towers during summer vacations from College in the early 1960’s. Signal jobs were hq’d at Harmon and Peekskill and most of the tower jobs were on the Harlem side including NW, JO, NK and RK. Seems to me like your dad was at JO then but could have been NW too — a long time ago. I remember a “Rudy” too but cana’t think of his last name or job.

Fantastic Story. I’m training as a dispatcher at Metro-North now. This really does a lot to explain why OW Tower and OW Yard were such important components of railroad operations