Back in 1980, the member railroads authorized the Association of American Railroads (AAR) to conduct testing of locomotives to study diesel exhaust emissions. The Research & Test Department was allocated a budget to develop a mobile testing lab that could be taken to railroad facilities to measure fuel and air flow inputs and emissions and power outputs of locomotives. Our test plan was to select locomotives that had recently been overhauled and compare their emissions of nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and sulfur dioxide to locomotives of a similar make and model that were at the end of their useful lives, just prior to overhaul.

The R&T Department had offices in Washington, D.C., where I was located, and in Chicago on the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology. The Chicago office conducted a great deal of testing in support of the AAR’s Mechanical Standards and had much useful equipment available. We converted a motor home they had into the new mobile lab and worked with a contractor that was experienced in measuring emissions from fixed facilities like power plants. Bench-work and equipment racks were designed and installed, measurement equipment purchased, computers acquired, (which we had to learn how to use—remember, this was 1980), and an array of other equipment obtained and outfitted. This is a little story about the creativity and ingenuity of some of the railroad people who actually made it work.

We spent some time at the Santa Fe’s Corwith Yard in Chicago to familiarize ourselves with the locomotives and determine how we would set up our equipment. They lent us a new SD40-2 and we did our initial test planning with that. Dry runs were conducted to see how everything worked before we went out to begin testing. Once we were satisfied that we had a workable plan, we arranged with the C&NW to set up at the 40th St. locomotive shop, also known as M-19A, for actual emissions and fuel testing to make sure everything worked properly.

It was a cold, windy, snowy Chicago winter. We thought if we could successfully test in Chicago under those conditions, we could go anywhere and work under any conditions. We were right and we were wrong.

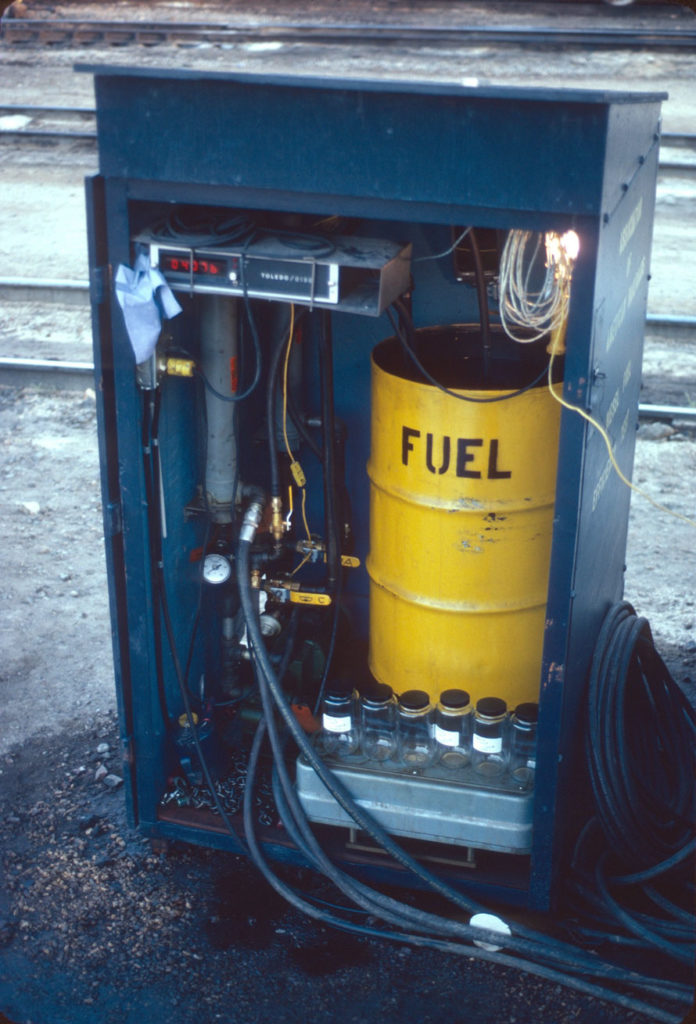

A key piece of equipment was a scale to weigh the diesel fuel used during a test so we could calculate how much fuel was actually used at each notch. It was a large platform scale, about three feet square, built by Mettler. Fairly heavy, it had to be moved with a forklift, and we didn’t plan to carry one around but instead to rely on each shop we visited for help getting the scale in place. A fuel line was connected from the locomotive to a 55-gallon barrel placed on the scale. Fuel from the barrel ran the engine during test mode. A return line from the engine to the barrel with a heat exchanger completed the system. Not all the fuel pumped to the injectors is used; some is returned, hot, to the tank, so we had to account for the actual amount used during a test by cooling the fuel and keeping the fuel in the barrel at a fairly constant temperature. Version 1 was just placed on an open platform and was exposed to the elements.

We quickly realized that the fuel measurement equipment needed to be protected from the elements. After some head scratching and sand house discussion with the Northwestern shopmen, a plan was hatched to build a small, portable building in which the scale and the heat exchangers would be housed. The fuel lines could also be stored in it when not in use. While we busied ourselves setting up our other equipment and working out just how the testing would be carried out, the shopmen were fabricating our scale house.

Like all good railroad shop men, these guys could do anything they set their minds to and do it well. In a just a few days’ time, they cut the wood, welded the frame, assembled the structure, installed the equipment, and painted and stenciled our new scale house. Truly a work of railroad artistry, or perhaps should I say, backyard art because it looked an awful lot like a building out behind the barn well known for its lack of plumbing.

It was a very cold couple of weeks; outside or inside it didn’t seem to matter, but we learned a lot about what would and wouldn’t work. The scale house was perfect. The motor home didn’t survive; we traded it for a utility van for the instrumentation and a flatbed truck to carry the calibration gas bottles, scale house, and assorted other equipment. We went on to perform our testing, in better weather for the most part, and carried out sixty-five tests at such fabled railroad locomotive shops as North Little Rock (MP), Salt Lake City (UP), Barstow (ATSF), and Sacramento (SP) over the next year or so.

While there was a statistically significant difference in emissions between freshly overhauled and end-of-useful life engines for the most part, there were too many variables that needed to be controlled during field testing to accurately model the effects of worn critical components and predict emissions as a function of engine condition. From this early work came more carefully planned and executed testing at test laboratories where the variables could be better controlled.

As part of the federal government’s efforts to reduce air pollution, national standards for locomotive emissions were established in 1999. EPA developed highly detailed testing standards for certifying locomotives to the emissions standards. Fuel used for emissions testing must meet strict specifications, so using fuel from the test locomotive’s fuel tank is not acceptable. Computer technology improvements have enabled more precise emissions measurements with vastly improved data analyses. And emissions control of locomotive engines now is more finely tuned with the development of computer-controlled fuel injection and on-board engine performance monitoring, resulting in significantly lower emissions in new and re-manufactured locomotives.

The locomotive manufacturers have labs for testing and certification of new and re-manufactured units. Laboratories such as Southwest Research Institute (SWRI) provide emissions certification testing services for the railroads and after-market emissions kit suppliers. We’ve certainly come a long way from our 1981 tests as you can see in the photos of the SWRI test facility.

Peter Conlon – Photographs and text Copyright 2021

Great story. I enjoy the more detailed technical aspects of railroad operations that are often overlooked. Steve Crise

This is in fact a very good story and well written. I went to the AAR web page to see if a public document of the official findings was published but could not find such a document. Did a report result from this research?

The report was published by the AAR in 1983 and copies distributed to the member roads. I don’t think that copies are available any longer since it is so far out of date. but you might contact the Transportation Technology Center, Inc. (www.aar.com) since they maintain the AAR’s research reports. I don’t even have a copy anymore. Locomotive technology and missions testing have evolved significantly over the last several years, making the results of our 1981-2 work obsolete.

Great story on something nobody talks about. In the early Penn Central days we had Alco diesels and the fumes that came out the stack! I think they would have destroyed your outhouse:-)

Peter

this is a great article and I wondered if you would give me permission to republish it in the NMRA British Region magazine Roundhouse?

Peter Bowen