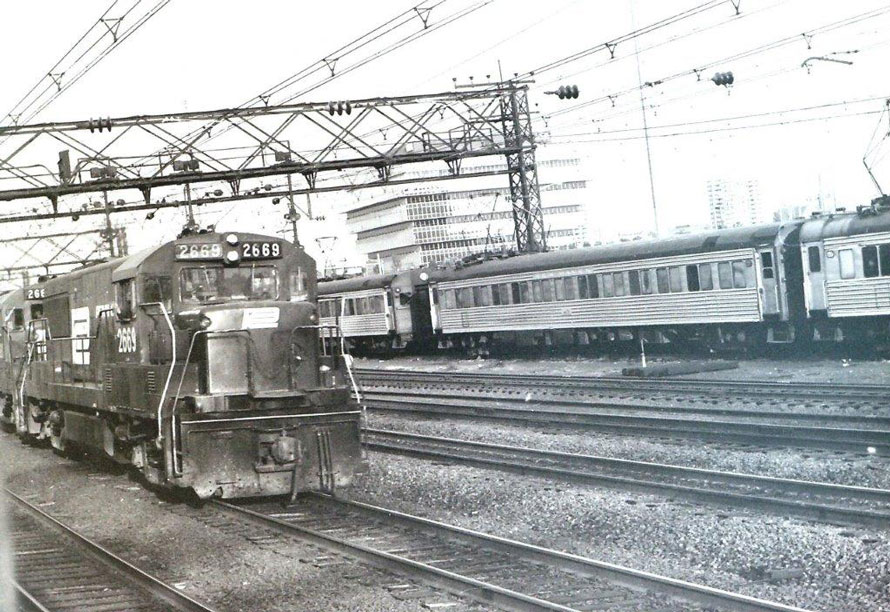

Back in 1970, we still had the sixteen-hour law and many freight jobs out of New Haven Connecticut, would work 15:59 so they did not outlaw. If you worked sixteen hours you had to have ten hours rest. But any other amount of time meant you only had to have eight hours off. Any job that went into New York had to have a fireman on it as they still had a full crew law; this was the way it was until about the 80’s. One of the jobs that went to New York was NH-1 that turned for HN-2. It was called the Drop as it made many stops along the way. The engineer on the job at that time was Joe De Cuffa, who was another great guy to work with and knew his job well. He enjoyed having firemen to teach and was the first engineer that started teaching me how to run a freight train. Before 1974, to become an engineer you were a firemen for a while, as a rule about three to four years. During that time you worked with many men and most would have you sit in the seat and show you how they ran their train. At the end of your years of doing it that way you took exams on rules, air brake, mechanical aspects of the engines and then qualifying on the characteristics of the road. That last part was where you sat with the rules examiner and he would take you from a point some place on the section of track you were doing to another part until he was satisfied you knew where you were. This meant each signal, switch, station, interlocking, speeds and any other special instruction you would have to know.

One night when Joe’s regular fireman was booked off I covered the job and while Joe was standing over me giving instruction he told me something I never forgot. He explained that on this job he counted how many times he could make a mistake, he counted how many signals, both hand as well as along the tracks he was on, how many times he put the brake on and if he did not control the slack in the train he would get a knuckle, and how many speeds he had to run between New Haven and Harlem river yard and back. When you think about an engineer’s job that way, it’s a bit mind boggling. There were none of the safety features then like today for back-up, just you and your firemen watching each other. Every engineer reading this knows what I am talking about. Each craft on the railroad has many rules to follow so there are no wrecks and/or people getting killed. At the end of each crafts day, from the people in the office to the trackmen on the ground, there is much that goes on that to seasoned railroad people becomes a way of life. That trackman standing out in the gauge has about four and a half feet that if he steps beyond has a good chance of getting hit by a train. That clerk who puts the paper work together for a freight train could make a mistake about a dangerous load in the wrong location of the train. This is a very short version of what the different crafts do to get a train over the road.

Remember, no radios so everyone had to be on top of their game. There was no room for errors.

NH-1 reported at Cedar Hill at 6:00 PM. Like all jobs, the foremen would give you the power and let you know it was ready. You would sign up and look at the bulletins that pertained to the railroad you ran over, the conductor would call the Yard Master and he would let you know when it was ok to come off the storage track and what track your train was on and if it was OK to tie on. If the car department was still working the train you would not tie on as the men were making sure doors were closed and brake shoes were all good. We still had some old style bearing’s on the freight cars that always needed to be checked for well-oiled rag waste so you did not get a hot box. After you tied on, while the engine crew did the brake test, the conductor was on the phone with the train dispatcher, the operator at New Haven East, and some other yard masters you would be dealing with along the way. If all went well we would be at the signal at Mill River about 7:30 give or take. Now the long night had begun. A good operator at New Haven East would let you know when you would get a shot through the station without stopping either in the cut or at the station. One of the best operators on second trick was Charlie Fullerton. He knew how to railroad and you always got a good move from him, he would be in the window of the tower waving to us looking the train over for sticking brakes, hand brakes, sparks of any type or doors open. Many people along the way always did that as well as trains you passed. If he saw a problem, since there were no radios back then, the operator running New Haven West would hold the signal at Woodmont against you and you would go to the phone to find out what the problem was.

Our first stop was East Bridgeport Yard for a set off. The conductor and brakemen would bail off as you went by the home board at Central Tower. The conductor went to the phone to call the yardmaster to get the track you would leave the cars on while the brakemen would swing you up with his light when you were getting close to the car he was to make the cut behind. After you stopped with the slack bunched up he would give you a go ahead and you pulled west toward the board at Peck Bridge and stopped. You were now clear of the eastbound signal at Central and after the hand-thrown yard switches were lined for the correct track, the conductor waved his light to the operator. At this point the operator at Central would line you from track one into the yard. Then he would tell the operator at Peck and he would dim and brighten the home board three times, and you knew it was safe to back up. After about a quarter of a mile, because the track is straight by this time, you could see the brakeman giving a big back up. He was watching the conductor east of him in the yard for a signal. You would drop your cars head pin and go back and tie on to the train and continue west, next stop East Norwalk.

When you made your stop at the East Norwalk station, the conductor had already spoken to the dispatcher and he knew you were going to be a few minutes while the firemen went to the diner up the street for coffees for the crew. Then you pulled down to the signal at Norwalk and blew the horn a few times. This let the operator at Berk Tower know you were ready to take some cars and shove them into Dock Yard for NX-6 and a yard switcher that worked there. Again, the conductor bailed off going by the switch for the Danbury main and walked to the yard, making sure the hand thrown switches were thrown, and relayed that he was ready to the tower. He in turn would give us the signal to shove into the yard. Most of this move was all done without hand signals because of the curves making this move. Remember, no radios so everyone had to be on top of their game. There was no room for errors. After putting the cars in the clear we would head pin and go back out and tie onto our train and be on our way to Stamford. I don’t think we stopped there every night. I believe BG-1 handled the cars for Stamford. So our next stop was New Rochelle New Yard where we left some cars and would then head down the branch.

Back then the signals were in service on tracks 5 & 6. Pelham Bay would cross us over to 5 and our next stop was Oak Point Yard. The operator at Market Tower knew you were coming and let the Yard Master know. They did everything they could so they did not have to stop you east of the tower. Back then,this area of the Bronx had people who were experts at disabling the train. If you stopped, they knew to close the angle cock and the brakes would not pump off when you went to move. During that time they always seemed to know what cars had beer or liquor in it. They were thieves, like you see on TV today. So everyone did their best to not stop you. You would pull down and the conductor made a cut and you continue with the head-end of the train to Oak Tower and he let you continue to Harlem River where you dropped the last of the train. You took the light engines back to Oak Point and the yard master had you come up an empty track and you would tie onto your train you would be going east with. While you were at Harlem River a yard crew would grab our caboose and tie it onto our train, we would get a brake test and let Market know we were ready to go east.

After leaving Oak Point we had a slot of time to get through New Rochelle, the morning rush hour trains were running and we had to get to Stamford for our next stop for picking up cars. We would leave our train on track 2, head pin, go to the yard, make our pick up after a break test and would shove out to our train on track 2, tie on, and head east to Bridgeport where we cut off and went into the east end of the yard. There was a diner up there and we would get coffee and some food. Then we grabbed a sting of cars, shove out to track 2, tie on and head east for New Haven. Next stop was the East Hump; we would drop the train head pin and bring the power back to the pit.

The paper work for the power would be taken care of by the engineer. The conductor had left the way bills for the train with the hump Yard Master and we called it a day. You worked all evening, night and half the morning back then. Went home, slept and did it again the next night. I hired in 1970 and saw the hours of service reduced from sixteen to fourteen, then twelve, which was one of the best things to happen to engine and train crews.

It’s been almost fifty years since what I told you about happened. As I always say, I am not writer, just a story teller. Hope you enjoyed this memory.

John Springer – Text and Photographs Copyright 2022

This story first appeared in the Penn Central Post, put out by the Penn Central Historical Society

Between 1965 and 1970, I routed NH1 and HN2 many times at most of the towers between SS4 Market and SS44 Berk. The story and photos bring back many fond memories.

Yes Steve I’m sure it does. And as I said in my story everyone had to be at the top of their game, no radio and night after night these moves were made flawlessly. We did the same thing at New London on NU-2 UN-1

If you ever wanted to feel like you were there, this story will make that happen. John Springer’s crews must have always been glad when he was handling their train because they would know he would be looking out for them at every move, and that at the end of that 16(!) hour day, everybody would go home safe. I will be re-reading this detailed and vivid slice of railroad history many times.

Thank you John, as I say I’m not a writer just a story teller and these are stories of my life as well as many other railroad men and women who did and do their jobs day in and day out. None of this takes place anymore so perhaps for some people I’m sure it’s hard to imagine even. Glad you enjoyed it.

Another exceptional trip down memory lane John ! The days of men of iron rails of steel and box cars made of wood. You brought those great old memories back to life for me.

Love the incredible detail here, John. Railroading has changed a lot in many ways since then.

Yes it has some for the better certainly not all.

Glad you enjoyed it Russ, I’m try to do these before I don’t remember them 🙂

I hired out in 1956 and worked all the towers east of New Rochelle SS22 to SS75 and handled NH-1,HN-2 many times. Railroading then was great and interesting. Todays operations are far from what they were then and not as interesting because the is almost no human contact any more. Railroading has turned a corner that it will never recover from. What it is today is the best it will ever be.

Hello Brother John. Very well written story. When I used to work BG-1 from time to time, all the old New York Freight conductors would talk about “The Drop” and they all said it was called The Drop because the entire engineer’s extra board would drop if the job was open.

Hi John. Thanks for the (not so fond) memory. But, most important, you must remember that all writing is “story-telling”. You are a writer, and your words reach us.

Epic storytelling! Thank you for the “memories”!

I would appreciate it if someone told me what “Head Pin” means.