The Project

This project’s title, From the Main Line, came to me since I began traveling throughout the Northeast exploring what survives and what developed as a result of the presence of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The project is the culmination of four distinct interests and their interaction: geography, history, architecture, and a life-long love of railroads. Among other reasons, I chose the Pennsylvania Railroad to satisfy a simple question; “Why would a company consider itself the Standard Railroad of the World?” I am sure many would argue that it was just plain arrogance, but that answer was not good enough. Starting in 2007 I set out to better understand the former PRR system by examining the various aspects of the railroad to create a cohesive survey of the railroad, its defining attributes and the landscape through which it traveled.

There are several concise topics that combine to create a holistic understanding of a railroad network and its effects on its surroundings. This approach can help one to identify the unique characteristics of any railroad corridor but specifically those that refer to the Pennsy.

My approach

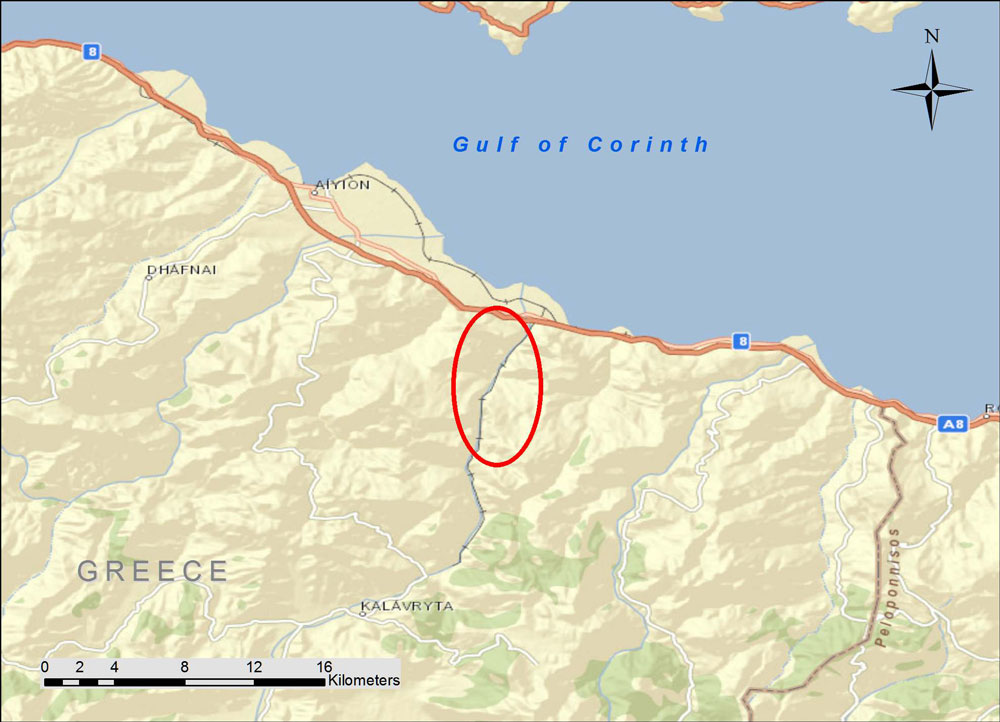

Unlike the railroads born of the United States’ westward expansion, the Pennsy was built and prospered in the established northeastern region. Much of the original route from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh followed a private rail line that was part of the Main Line of Public Works (MLPW), a combination canal and rail system that ultimately failed. In 1854 the PRR bought the MLPW, and later the canals were filled in. Forges, mines, and transportation centers had formed around the canals, but flourished after the arrival of the railroad. Highlighting this history of the neighboring landscape was important to establish the visual identity of a very distinct topography.

Over this topography, the railroad traveled through a landscape both remote and civilized, but the physical plant itself is a unique engineered landscape, often identifiable by vernacular attributes specific to the railroad that constructed it.

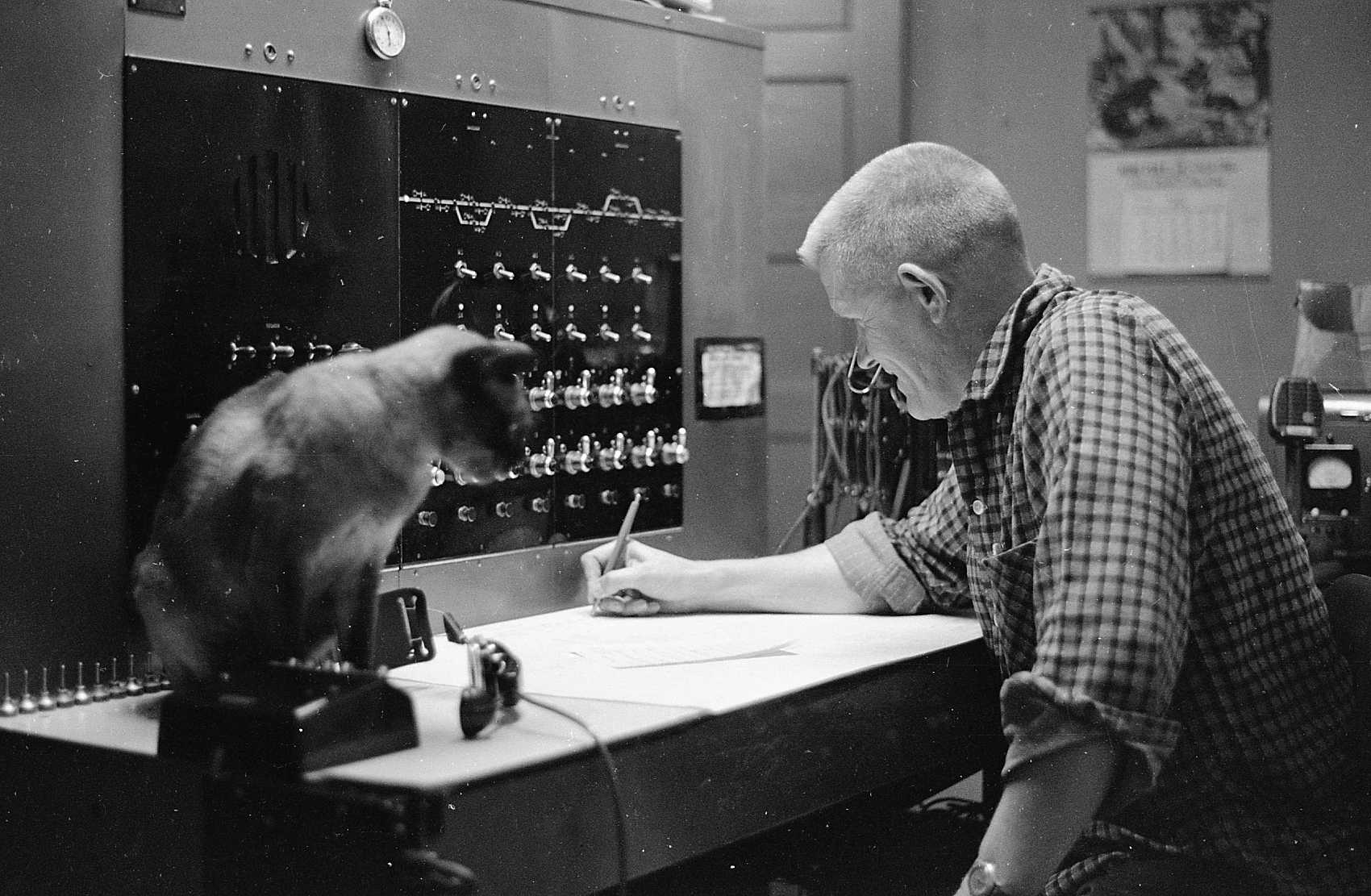

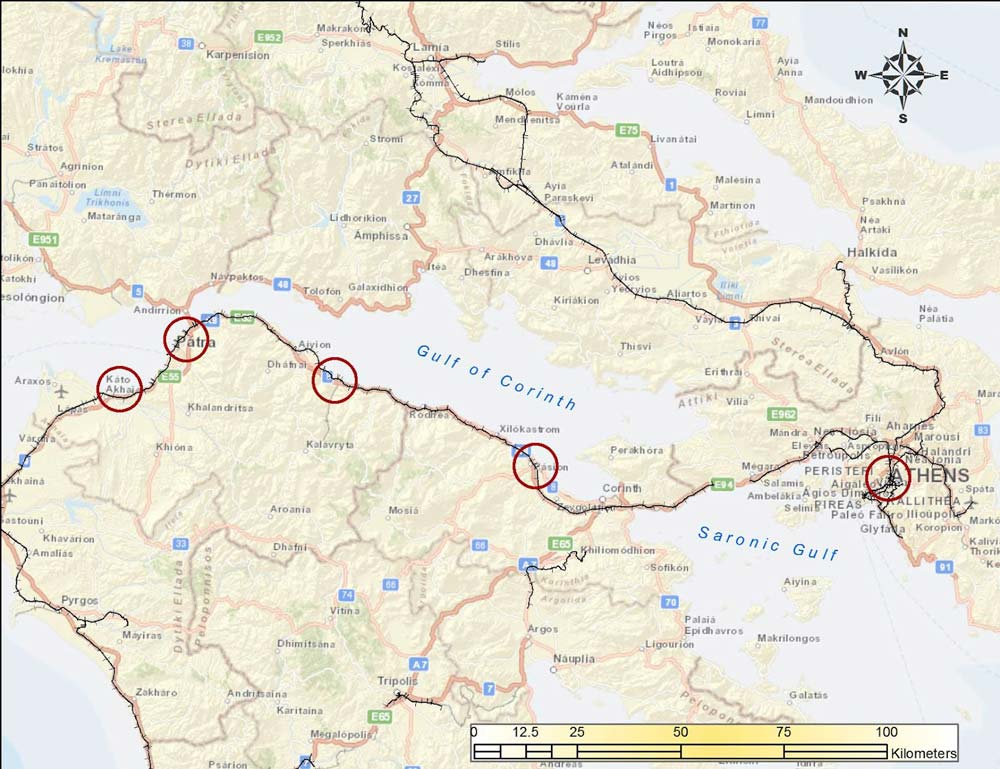

The right-of-way is perhaps the most recognizable attribute of the railroad. The Pennsylvania Railroad was a two-to-six-track wide main line that cut across the land on a highly engineered corridor largely separated from the outside world. A result of years of refinement, this infrastructure allowed the PRR to move countless trains using traffic management systems that enabled fluid operation of both freight and passenger traffic within shared track space. Linking towns, cities and industry, the right-of-way of the Pennsylvania Railroad is immediately recognizable and stands out among its peers due to its sheer magnitude. East of Harrisburg, the towering poles and tethers of wires for the electric traction system further define the right of way and has distinction as the only surviving long-distance electrified mainline in the United States.

The right-of-way supported transportation networks vital to the public and industry. An extensive passenger network moved people on long distance, regional, and commuter trains from stations that ranged from monumental metropolitan gateways to a simple frame structure. It was also the supply chain for industry, connecting line side mining, manufacturing, steel production, and deep-water ports. Most of the freight was moved on the Low Grade, a freight bypass built between the Delaware and Susquehanna rivers. This route was a testament to the PRR’s engineering prowess and a final piece of the railroad’s massive system-wide improvements at the turn of the 20th Century that would make the railroad worthy of the title, Standard Railroad of the World.

The railroad corridor is an assemblage of engineering feats used to manage high volumes of traffic, setting it apart from other railroads of the era. Ranging from bridge construction, the massive flying junction, the interlocking technologies that controlled them and the electrified rail network east of Harrisburg, the PRR spared no expense to improve efficiency and capacity. Fortunately, surviving elements provide insight on how the railroad functioned, including the many stationary and movable bridges, terminals, and extensive interlockings throughout the system.

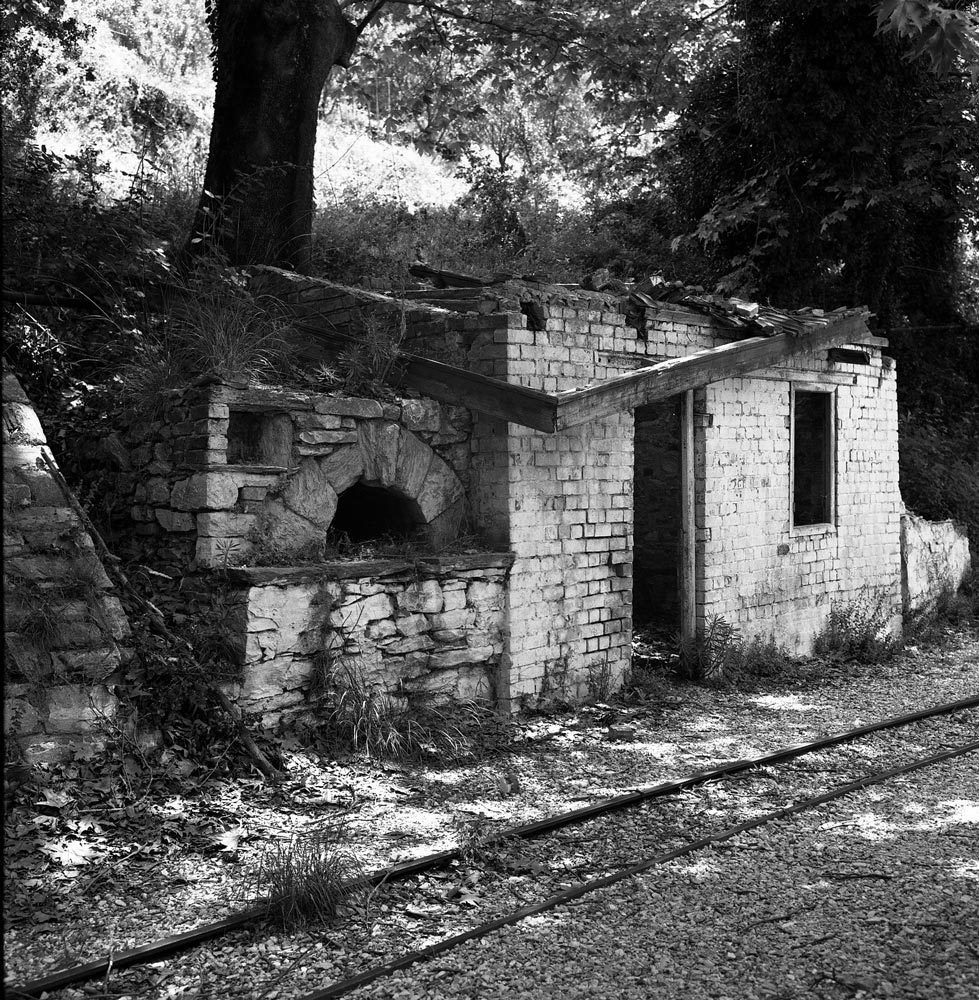

Perhaps one of the most challenging aspects of documenting a railroad that has been gone for more than 45 years is envisioning what was lost in order to understand how the original network worked. Whether a result of recent or ancient railroad history, it is the archeological aspect of this project that requires the most imagination to complete the puzzle that was the Main Line network. There was considerable abandonment and change after the fallout of Penn Central and the creation of Conrail and Amtrak which forever changed the railroad landscape and operations. As a result, defining attributes like the Low Grade and many of the interlocking towers and stations were abandoned, eliminating evidence of the larger unified system.

Research is the element that ties everything together: the stories, history, triumphs and failures behind the surviving objects and places. Utilizing historical photographs and maps adds a layer of context to the contemporary images, something that was absent in my earlier work. Understanding the historical significance gives me a better perspective of a place before I visit and allows me to create more informed images. Putting together my findings, and sharing information fuels the creative process. This element in the Main Line project allows me to expand the reach of my audience beyond the rail community, connecting with the casual observer, historian, architect, and engineer alike.

A Conclusion

My goal when I set out was to satisfy a curiosity, but what I think I have done is expand my use of photography to become part of a larger idea interpreting the social, industrial and railroad history in a creative and accessible way. As this project continues I start to ask the question, was the PRR the Standard or the exception in the railroad world, doing things differently literally from the ground up? When will it be done? I don’t really know. I just know railroads have been a life long interest, and it’s nice to combine it with my creative work. I hope that my approach to railroad photography will inspire others to explore and understand their favorite railroad differently the next time they are out on the main or even a branch line operation.

The Trackside Photographer is pleased to present a gallery displaying 40 images from Michael's project. Click here to view the gallery, or go to the Galleries menu at the top of the page.

Michael Froio – Photographs and text Copyright 2016

See more Michael’s work and his blog Photographs & History at www.michaelfroio.com