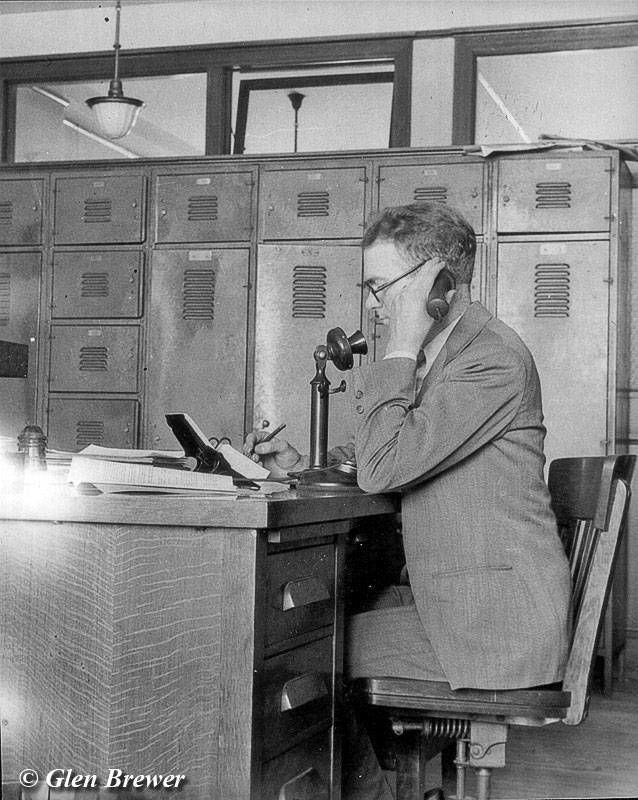

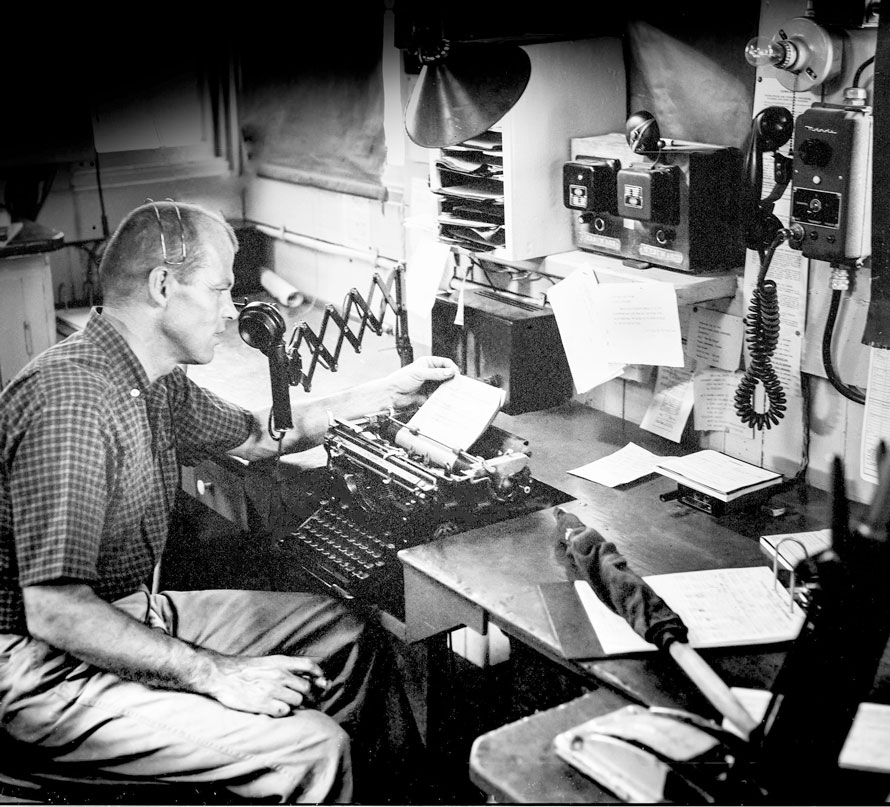

This is Dale Bryan, thirty-three-year-old Southern Pacific relief second-trick telegrapher-clerk at Paso Robles, California (Paso de Robles/pass of oaks) on a warm July evening in 1960. And these are the tools of his trade:

Clockwise: earphone; scissors phone; shelves for 3-, 5-, 7- and 9-copy blank train-order forms (with carbons at the ready); dispatcher’s loudspeaker; westbound and eastbound annunciators (‘bells’); Motorola radio; clearance cards; telephone line ‘jacks’; ‘O.S.’ sheet; levers for westbound and eastbound train-order semaphores (‘order boards’ on the SP); a red flag and of course a classic Underwood typewriter. Although he is still referred to officially as a ‘telegrapher,’ Dale no longer has Morse code in his job description: the key and sounder were removed three years earlier. The new-fangled Motorola is the future of train control.

By 1960 Paso Robles, with its single overhead bulb burning in the dark, was the only fully-open, 24-hour train-order office remaining between Santa Margarita (which is north of San Luis Obispo and at the foot of the Cuesta grade) and King City. This is a distance of 75 miles.

What I remember is the understated manner with which Dale handled his duties while engaged in a great enterprise with all its dangers and opportunities to make consequential mistakes. Train-orders on single track were often about taking time from superior trains and lending it to inferior ones. Dale needed to transcribe his dispatcher’s orders quickly and with complete accuracy because as little as a typo would invalidate the order and stop a train. What’s more, that error would be magnified over distance causing further delays and recalculations up the line. No pressure then!

And Paso Robles’ annunciators gave minimal warning. How much ground did No. 99, the westbound Coast Daylight, cover in two-and-a-half minutes? The classic Hollywood films High Noon (Gary Cooper) and Suddenly (Frank Sinatra) drew on the dramatic potential in a rural California station like Paso Robles. Cue the ticking clock and the unseen inevitability of a fast-closing express.

The railroad will always be about time and distance

It’s worth remembering that the railroad in those days didn’t run only on rails. It ran also on an invisible matrix with real people passing detailed computations of time and distance from one to another. And these computations were of great importance, since the railroad was literally the main line of commerce and communication.

Now I guess it’s only natural that the sight of my old friend at his operator’s desk sixty years ago will shout analog, even if many of us do find historical railroad technology important and interesting. But whether analog or digital, steam or turbocharged diesel-electric, the railroad will always be about time and distance. From this modest station and using comparatively primitive and manually-dependent communications, time was given and time taken away. How many people could put that in their job description?

Read more