It was a cool day in late October in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The buildings I had come to see were bathed in the warm light of a late autumn afternoon and all was silent and still behind the vacant windows. It wasn’t always so.

Read more

It was a cool day in late October in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The buildings I had come to see were bathed in the warm light of a late autumn afternoon and all was silent and still behind the vacant windows. It wasn’t always so.

Read more

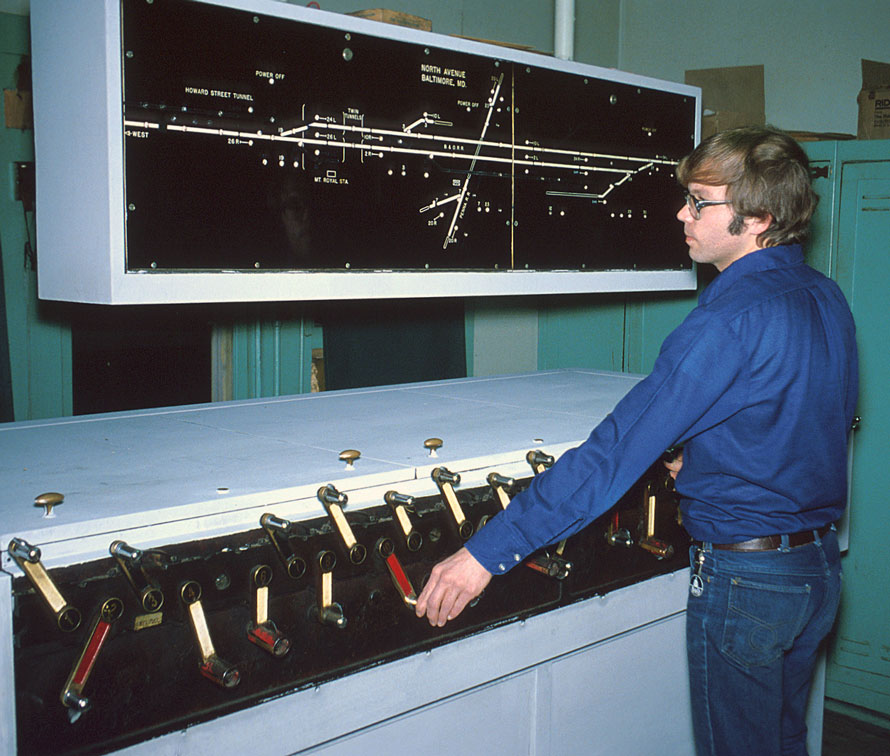

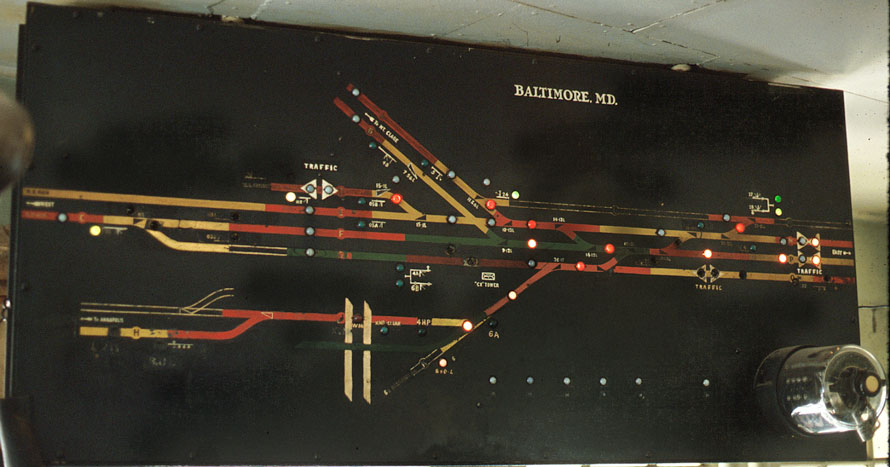

The interlocking tower, while not totally gone, has virtually vanished from the railroad scene. Whether it was a humble one story shanty or a magnificent two, three or more stories tall building, they once served a vital function. Some controlled where double track went to single; others controlled where two or more railroads crossed; others controlled a vast and complex passenger station “throat”.

Towers could be built to a particular railroad’s standard blueprint, but they all had their own personality. It was easy to recognize a certain railroad’s tower. Pennsy had it own look, as did the New York Central, Erie and the rest, but no hard and fast rules applied, even within the same railroad.

The inside of an interlocking was a fascinating and magical place.

Watching the operator going about his duties was a sight to behold. There was always something going on; the constant chatter on the dispatchers line, the “ding” of the bell notifying that a train was “on the circuit “, or the operator transcribing a train order. The special smell of the grease used to lubricate the throw rods added to the ambiance.

With the advent of CTC, radios, and more recently computers, it is now possible to control hundreds of miles with only one dispatcher. Downsizing the physical plant and outright abandoning of portions of the railroad helped hasten their demise.

Dan Maners – Text Copyright 2016

Photographs Copyright 2016 by the photographer credited in the photo captions.

See more of Dan’s work at his website: North American Interlockings.

Rail fans come in many flavors: train watchers, history buffs, modelers seeking details, technical enthusiasts, equipment lovers, and photographers both hobby and serious. Point of Rocks has it all with robust rail traffic as an added bonus.

The station itself is the shinning jewel. Designed by E. Francis Baldwin in the Victorian Gothic style and built by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) in 1876, it remains as one of the most beautiful of historic rail road structures. It is not opened to the public and is used by CSX as an office. In 1931 it was struck by lightning and gutted by fire. We can be thankful that the B&O ordered its full restoration.

The station sits inside a wye formed by the junction of two former B&O mainlines (all tracks are now owned by CSX). The south side of the wye (shown above) is the Metropolitan Subdivision which carries most of the traffic you will see here and moves CSX freight east and west. This is the “new” main line completed by the B&O in 1873. The north side of the wye is the Old Main Line Subdivision and carries trains to Baltimore. This is the original B&O main line completed in the mid-1800’s. The east side of the wye connects these two main lines and is used primarily by Maryland Area Regional Commuter (MARC) trains diverging from the Metropolitan Sub to the Old Main Line Sub and eventually to the Frederick Branch.

Just west of the station is the Point of Rocks tunnel. The original single-track main line is the track on the left which goes around the cliff. The tunnel was completed in 1902 when it became necessary to add a second track. The tunnel portal is an interesting brick structure with “Point of Rocks” cleverly spelled out by protruding bricks. Both the east and west portals are of the same design. Most tunnel portals are drab concrete affairs but from time to time the railroads made the decision to get fancy. Another good example is the old Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Ft. Spring, WV tunnel which is of a classy art deco design.

Just over the river bank from the original main line was the Chesapeake& Ohio Canal (C&O). Space is tight here and the rail road and canal folks were often at odds. A wall between the two was constructed to help ensure the trains did not scare the mules pulling the canal boats

“Less than the width of a baseball diamond. For a quarter mile at Point of Rocks the space between the Potomac River and the mountain is that narrow. The C&O Canal Company and its arch rival the B&O Railroad were sure both a canal and a railroad wouldn’t fit there. Which one would get the land needed for their project? Who would decide? How long would the decision take?

These are things that intrigue me about Point of Rocks. The C&O Canal Company believed they owned that strip because their predecessor, the Potowmack Company, had owned the land. The B&O Railroad fought this and the dispute went to court in 1828. It took four years for the court to decide in the Canal Company’s favor.

In the end the C&O Canal Company came to an agreement with the B&O Railroad because the canal company needed the money. They managed to squeeze a canal and railroad into this narrow strip. It still didn’t quite fit. To make more room the B&O Railroad later blasted a tunnel through the hill next to the canal. Both companies operated side by side until the canal closed in 1924.” – Ranger Lisa – CanalTrust.org

For night photography Point of Rocks has a pleasing array of lights which are helpful in illuminating the area, lessening the need to use a flash (I actually never use a flash for night photography). The well-lighted areas also provide a measure of safety when moving about trackside. My only complaint, and it’s a minor one, is that I wish the station had some exterior lighting.

I grabbed a few shots of commuters de-boarding the MARC trains. I’ve never had any real objection to people showing up in my images. Most often, unless they are blocking the critical elements of a composition, they can add interest to an image. I enjoy capturing the hustle and bustle of folks coming and going about their daily routines. In large cities like Chicago or New York the mass of souls moving about can be quite fascinating.

The MARC Brunswick Line runs 9 east-bounds and 10 west-bounds through here Monday through Friday. Not all of them stop here though. I’m not clever enough about train movements to understand how that 9/10 train schedule works. In addition, the Capitol Limited goes by twice a day seven days a week—one west, one east. Those 21 passenger trains are a nice addition to the already busy freight traffic.

My recent trip to Point of Rocks (September, 2016) was my first and I look forward to a return. My primary interest in such places revolves around railroad photography and this beautiful place offers a rich array of photo opportunities. I did not explore all potential locations and following my return home I’ve thought of other compositions I’d like to explore. A little east of the station along the Old Main Line there is a grade crossing. From looking at Google maps it appears there might be some nice views looking back west towards the station.

Saying goodnight from Point of Rocks and wishing you Happy Rail Fanning!

Fred Wolfe – Photographs and text Copyright 2016

See more of Fred’s work at http://fredwolfe.Zenfolio.com or find him on Facebook at Wolfelight-Images and at http://www.facebook.com/fred.wolfe.98

Grain elevators have fascinated me as long as I can remember. Growing up in the Midwest meant seeing these unique buildings along the tracks of even the smallest communities. Symbolic of the agrarian roots of the region, they were often the tallest and most imposing structures in farm belt towns. Along the granger railroads that I grew up with, the grain elevator was as much a fixture of the trackside infrastructure as the depot. Because of that, grain elevators have long played a role in my railroad photography—so much so that I often made an effort to photograph them even if there wasn’t a train around for miles.

When I moved to Denver, Colorado in 2001, I was enthralled to find that the grain elevator was as prevalent on the high plains of eastern Colorado as it was back home in Illinois. Once again, I found myself taking photos of these magnificent structures. Something happened in early 2010 that really sealed my commitment to this exercise. One day while driving past Bennett, CO, I noticed that the old wooden elevator there was no more! Seeing the bare ground where the elevator had once stood hit me hard. Shortly thereafter, I decided that I really wanted to start documenting as many of Colorado’s remaining elevators as I could before other elevators suffered a similar fate.

My initial efforts were about as documentary as a three-quarters wedge shot is of a locomotive. I tried to shoot with good light but the compositions were all similarly nondescript. They were serviceable as illustrations but hardly noteworthy in any artistic way. I think my goal at the time was merely to photograph as many as I could before they were gone. On a very cold February 18th, 2012, though, that all changed. I arrived before dawn to get morning light on the Eastlake elevator north of Denver. When I arrived, there was a really nice crescent moon just begging to be photographed. I had my tripod and quickly set-up to photograph a “blue hour” shot of the elevator, something I hadn’t tried yet. When I got home and compared that image against my more typical shot after sunrise, I was smitten by the additional grace and beauty of the moon scene as a whole. Indeed, the elevator became even more interesting to me. After that, I really started challenging myself to see elevators in new ways by looking at details, placing the elevators in the environment where they reside, incorporating vehicles and other elements into the frame, etc. These all became new photographic tools for me.

2012 proved to be a wonderful year for the project in another way, too. That was the year that I came across the grain elevator page of Gary Rich. Gary’s PBase page (http://www.pbase.com/grainelev) was full of information about the grain elevators of Colorado and many other states. It was also full of wonderful elevator imagery. Gary has since become a great friend and we have gone on many grain elevator photographing excursions together.

That quote has come to embody precisely how I approach my grain elevator project now. When I take a photograph of an elevator, I’m hoping to convey exactly how these magnificent structures move me. I want the viewer to feel the same appreciation I do for them, both as beautiful buildings and as symbols of the men and women who have toiled for generations to feed the country. If I can succeed at that, the project has been worth the effort I have put into it.

Click on photograph to open in viewer

The 1,067mm (3’6″) gauge network in the Australian state of Queensland is dominated by heavy coal and mineral traffic moving from mines to ports, and some intermodal traffic heading up the coast from the capital of Brisbane. Until a few years ago though, there were some scattered remnants of trains that belonged very much to the previous century—in spirit at least.

One such service was a weekly train that ran to the south-west outpost of Dirranbandi. Built in stages starting in 1904, the line arrived at its eventual terminus in May 1913. The line was built to serve small communities in the area, and like most such lines around the world, carried out its role of bringing in the essential supplies needed for rural living, and taking out the products of the land, in this case cattle, sheep, wool and grain. This line served a second purpose, hinted at by its early nickname of the Border Fence: to prevent this traffic from moving south to travel over the rails of the rival state of New South Wales.

The importance of the line was declining rapidly when I travelled out that way in 2007 and 2008. General freight was virtually non-existent, but the line beyond the major grain silo at Thallon still saw a weekly freight train working out and back. The train wasn’t much to look at—a handful of vans—but still a sight worth seeing if only for its anachronistic nature, a fact acknowledged by the train’s driver who, when we got to talk at one of the stops along the way, cheerily exclaimed that it was good to see someone photographing one of Queensland Rail’s last dinosaurs.

The country out this way is pretty lonely. Large grazing stations and very little population are the order of the day, with the little train heading over the light 42 pound rail and spindly track well away from pretty much anything, apart from the endless scrub and the occasional siding with a disused woolshed. Sometimes a kangaroo or two might nonchalantly cross the line. Not far from Dirranbandi, the grain silo at Noondoo would be passed. For the line’s recent history, it was this silo that justified keeping the line open. The light track meant that grain wagons could only be partially loaded. The obvious solution was to upgrade the line, but the railway and the grain shippers couldn’t agree on who’d pay, so rail service stopped and the grain had to be trucked over to Thallon, which still happens.

On my first trip, Noondoo was a silo-in-waiting, with the surrounding paddocks barren of grain but a year later, after the first decent rains in years, the land was alive with activity. The railway though, played no part.

Here at Hawkston, about halfway on the very light rail, there is some evidence of human activity, with a small but quite elaborate storage box built to receive the newspapers that used to be dropped off by the passing train until quite recently. Located on the long dirt road to the grazier’s home, a stop by the train would eventually be followed by the farmer driving out to collect the newspapers.

I’m not sure if there was ever what could really be described as a station at Hawkston, and it’s a pretty safe bet to say that if there was it would never have had a station master, but I liked the ironic humour of the locals, allowing such a minor item of infrastructure to take on added importance, while the train disappears into the hazy distance.

Alan Shaw – Photographs and text Copyright 2016

See more of Alan’s work on his Flickr page

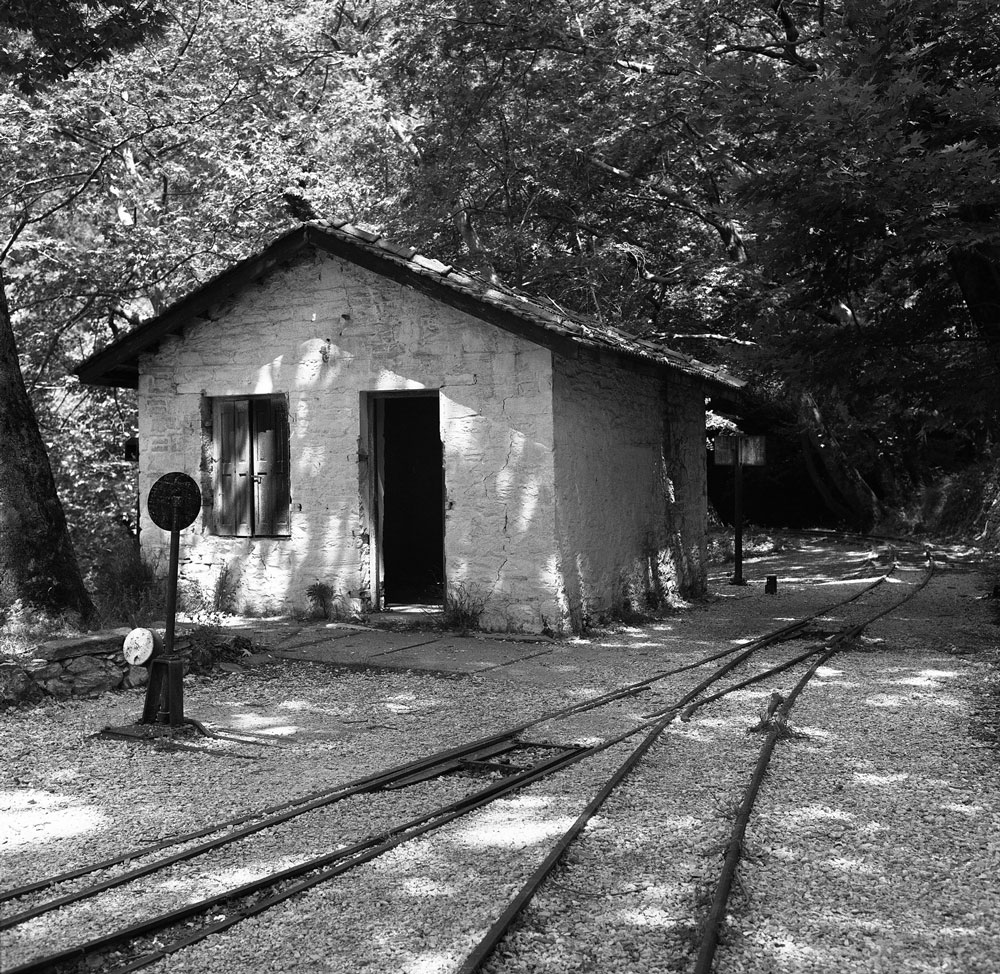

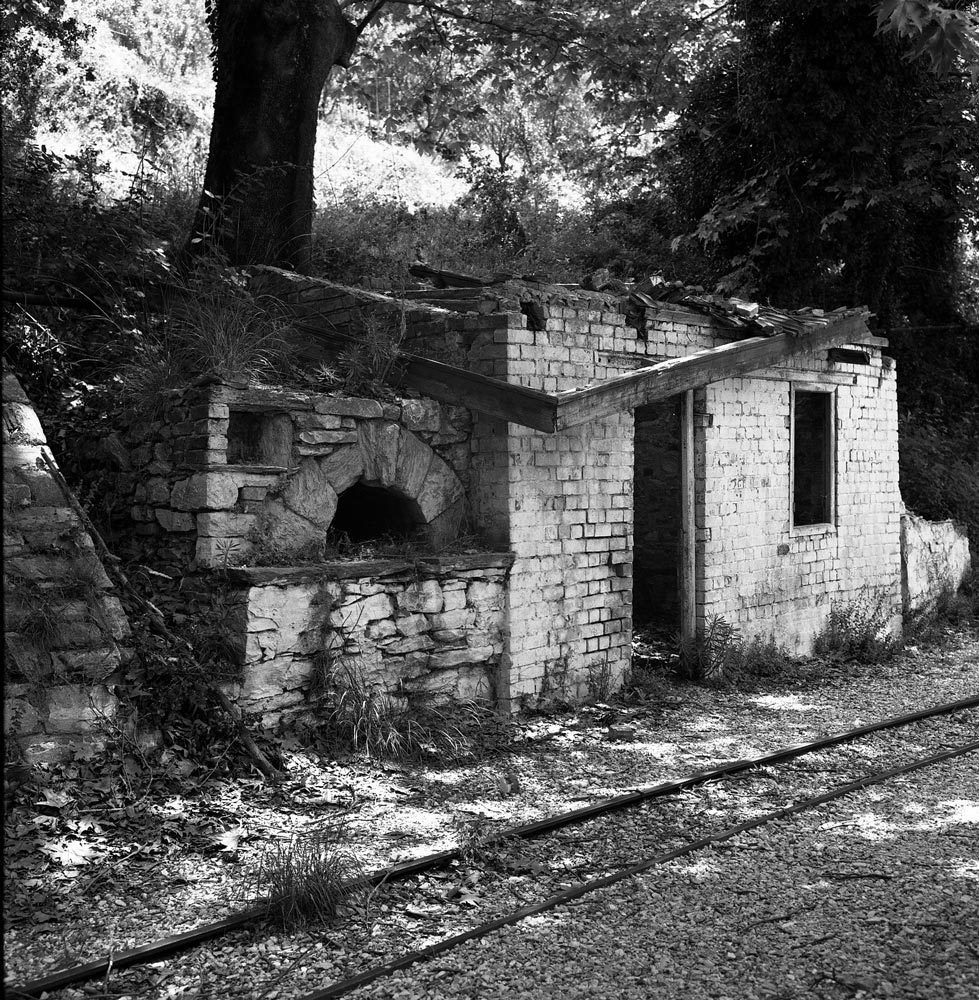

The quiet village of Milies (Greek: Μηλιές) is the end station for the narrow gauge line that runs from the seaport of Volos into the interior of the Pelion Peninsula. Pelio is a rugged, mountainous region in east central Greece.

The lush mountainsides are draped with forests of beech, chestnut and plane trees, and the cherries, apples, and apricots are said to be the finest in Greece. Pelio was so rugged, it had little communication with the rest of Greece until the late 1800s. In winter, heavy snow makes roads impassible. During the centuries of Turkish occupation, the Greek villagers here were renowned freedom fighters.

Because access to the mountainous peninsula was so difficult, the goal of the railroad project was to improve transport and integrate the area into Greece’s economy. According to Wikipedia, “The 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) gauge 27 km line from Volos to Milies, a distance of 28 km, was constructed between 1903 and 1906 by the Italian engineer Evaristo De Chirico.” Service began in 1906. Construction was very difficult because of the need for six stone bridges, one iron bridge, many protective walls, tunnels, and aerial pedestrian bridges. The photograph above shows an example of the arch bridges, all built by hand by skilled rock masons.

When I took these photographs in 1994, the line was unused and the setting had a charming, sleepy, overgrown look to it. Service was discontinued in the 1970s, but may have been restored recently for steam locomotive tourist trains.

In the 1990s, there was a well-known bakery here where Athenians would buy bread before returning to the city (about a 5-hour drive to the south). The village ladies above had probably seen it all—strange tourists with tripods and cameras, and city-slickers with bags of fresh bread and cherries.

The Piraeus, Athens and Peloponnese Railway was a narrow gauge (1.00-meter) line that once connected small towns in the Peleponnese area of Greece with Athens. Our trip will carry us along the rails from the west end of the Gulf of Corinth to Athens.

The circles show locations of photographs. Background maps from ESRI Maps and Data.

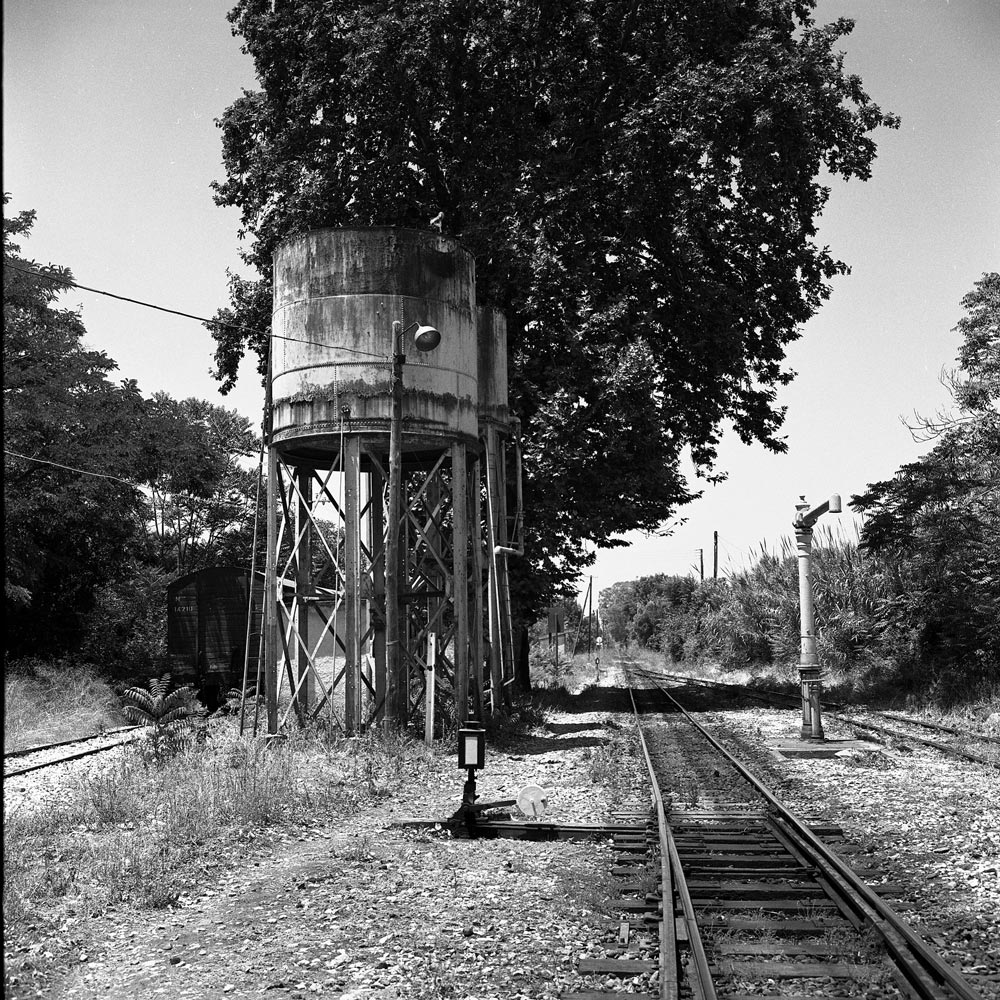

This is the station at Kato Achaia, a farming community west of Patras. It has a sleepy land-that-time-forgot look to it. The water tank for steam locomotives still stands. As I recall, the train was delayed and we sat at a café for an hour or two.

As of 1997, the train consisted of modern but well-used diesel-electric rail cars. The windows were open and the train trundled along through vineyards and orange groves.

In Patras, we had to change trains for the main line to Athens. This was a busy station because tourists from Italy disembarked from ferry boats and many boarded the train here.

You see some refugees or gypsies on a bench. A historical note: After the Communist Bloc collapsed in 1989, thousands of Greeks from Bulgaria, Romania, and other countries were finally free to return home. Some had been stranded in the Soviet Union since the 1917 revolution. In Czarist Russia, Greeks were an important part of the merchant class and traveled throughout the vast land, but when the Bolsheviks imposed Communism, the Greeks were unable to leave. Many of their descendants spoke no Greek and had not been able to worship in Orthodox churches. After 1989, Gypsies (the Roma) also were able to travel across borders that had formerly been sealed. Finally, Albania, once a forbidden dictatorship every bit as secretive as North Korea is now, collapsed, opening the borders to thousands of impoverished Albanians who desperately wanted to find work in Greece. The people on the bench may be gypsies. These refugees have caused major disruptions to Greek society and its fragile economy.

This “Splendid” hotel was across the street from the Patras rail station. It was probably clean enough but noisy; I will pass.

The next major junction was Diakopto, where tourists could take the famous rack train up the gorge to Kalavrita.

Further east, the station at Narantza has not been used in decades. I used to vacation near here, and from my sister’s house we would hear the trains periodically rumble by. One engineer was distinctive because he tooted the horn more than other train drivers. Continuing east, the train would have stopped in the city of Korinthos.

Then the train crosses the narrow Corinth Canal (Διώρυγα της Κορίνθου), which connects the Gulf of Corinth (Korinthiakos Kolpos) with the Saronic Gulf (Saronikos Kolpos). The canal, dug in the 1890s, is narrow and mostly used by cruise boats.

Finally, after chugging through the industrial suburbs of west Athens, we reached the Peloponnese Railroad Station on Sidirodromon Street (built in 1889). It was pretty sleepy in 1997 and some men were sitting around playing backgammon and drinking coffee (Greek gents do a lot of this). I think the station is now unused and am not sure what its fate will be.

(This is Part 2 of a two part article on the Railways of Greece. Click here to read Part 1)

Andrew Morang – Photographs and text Copyright 2016

See more of Andrew’s work at his blog, Urban Decay.