The Athens to Peloponnese Railroad Station

Corinth, Greece

The Piraeus, Athens and Peloponnese Railways or SPAP (in Greek: Σιδηρόδρομοι Πειραιώς-Αθηνών-Πελοποννήσου or Σ.Π.Α.Π.) was founded in 1882 to connect the port of Piraeus (Πειραιεύς) with Athens and the Peloponnese region of southern Greece. The late-1800s was the era of great railroad building throughout the world. Greece, at that time a poor nation with isolated market towns and limited roads, hoped to support economic development by building a rail system. The Peloponnese line reached Corinth in 1885 and Patras in 1887. SPAP was absorbed by the Hellenic State Railways in 1962, now called OSE (Greek: Οργανισμός Σιδηροδρόμων Ελλάδος or Ο.Σ.Ε.). The Peloponnese rail was 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 ⅜ in.) narrow-gauge, in contrast to the continental-standard 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 ½ in.) used in most of mainland Greece. The line from Piraeus to Corinth was 99 km long. In the 1890s, it was the fastest way to make the journey, the alternate being a steamship trip.

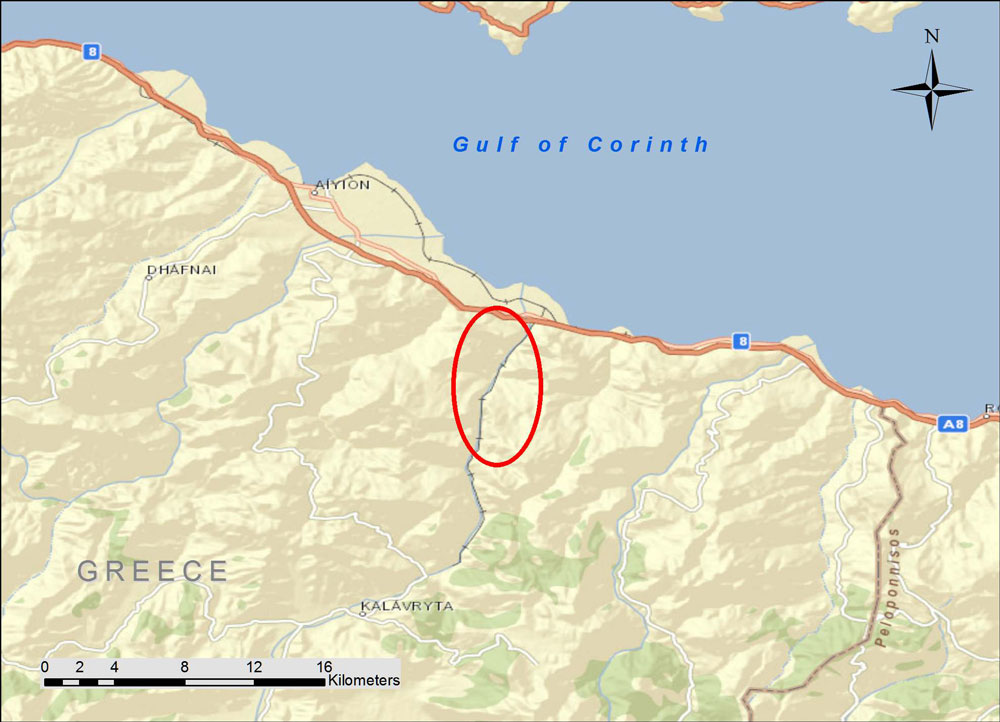

The map shows the location (background street map from ESRI maps and data). During the mid-20th century, tourists arriving from Italy typically took a ferry boat from one of the Italian Adriatic ports to the city of Patras, where they disembarked. Then the SPAP train took them on a leisurely day-long ride to the old central rail station in Athens. Once the modern highway was built in the 1960s, many travelers took diesel buses instead. As a result, they rushed past the charming little market towns clustered along the shore of the Gulf of Corinth and missed the train experience.

Today, the rail station in Corinth on Dimokratias Street stands semi-abandoned. As of 2005, the modern suburban rail connects the Athens Elefthérios Venizélos (Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος) International Airport with Corinth and, now continues further west to the town of Kiato. Eventually, the modern rail will extend all the way to Patras, and the rest of the historic narrow gauge train will be discontinued.

This station looks like it is late-1940s or 1950s-vintage. Corinth was badly damaged by an earthquake in 1928, and possibly that eventually necessitated a new station. Another hypothesis: The railroad suffered extensive damage during the second World War, and maybe the original station was damaged.

In 2011, the rail yard was pretty quiet, with abandoned rolling stock sitting on sidings. The arm sticking out in front of a graffiti-covered box car is an old water tap for filling the tenders of steam locomotives.

Finally, these mechanical control units actuated track switches. Oddly, they were on the platform in front of the station waiting room. Wouldn’t tourists be tempted to fiddle with them? It’s strange they had never been electrified or adapted to control from a central control room.

The Kalávryta Narrow-Gauge Rack Railroad

Peloponnese, Greece

The Kálavrita (Καλάβρυτα) Railway was engineered by an Italian company in 1885-1895 in the fantastic gorge of the Vouraikós River. The original steam locomotives are long gone and have been replaced with modern diesel-electric cars, but nothing detracts from the magnificent scenery or from the achievement of the engineers some 120 years ago. The route starts in the coastal town of Dhiakftó and proceeds south (uphill) through the gorge to a high fertile plateau. Kalávryta is in the East Central part of the prefecture of Achaea. You can drive there through the mountainous and scenic Peloponnese, but many people opt to park their car at Dhiakftó and take the famous train for a day-long excursion.

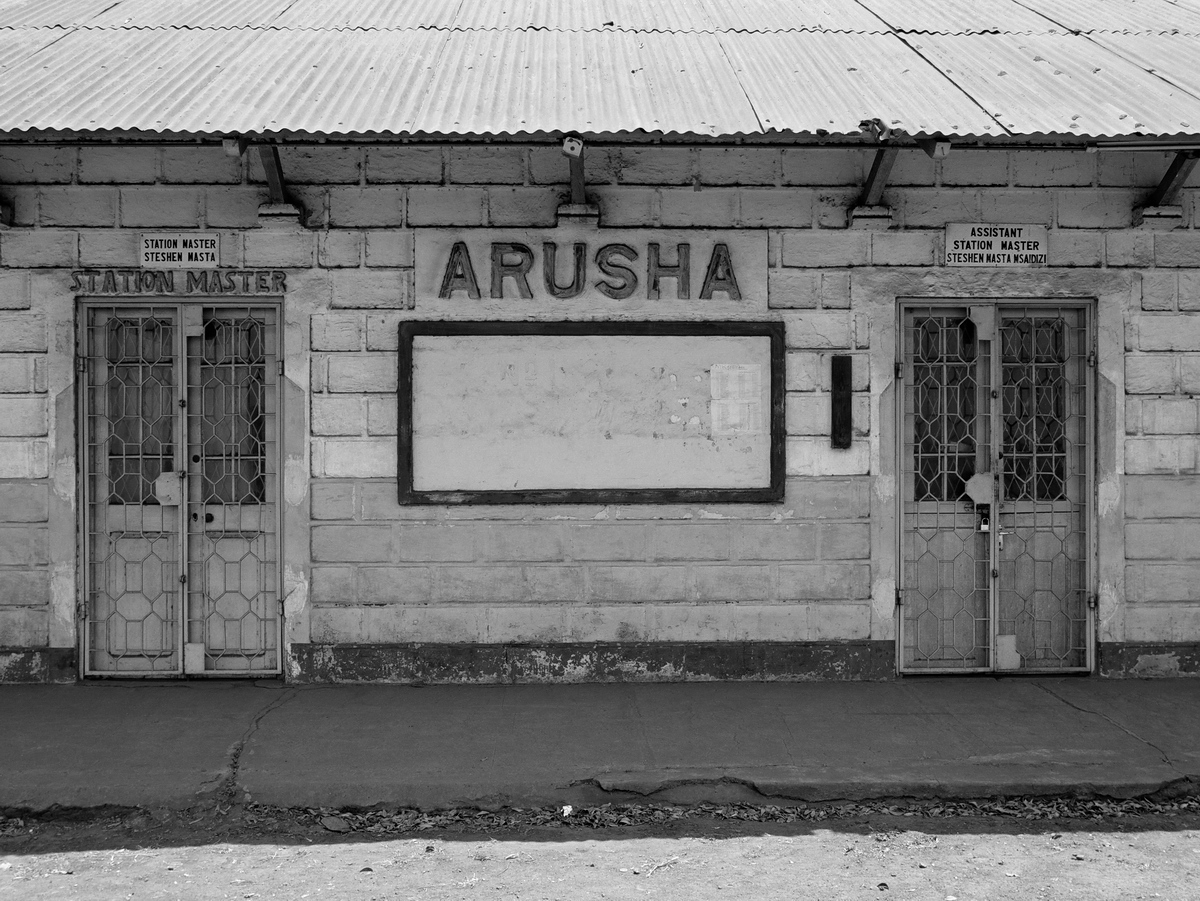

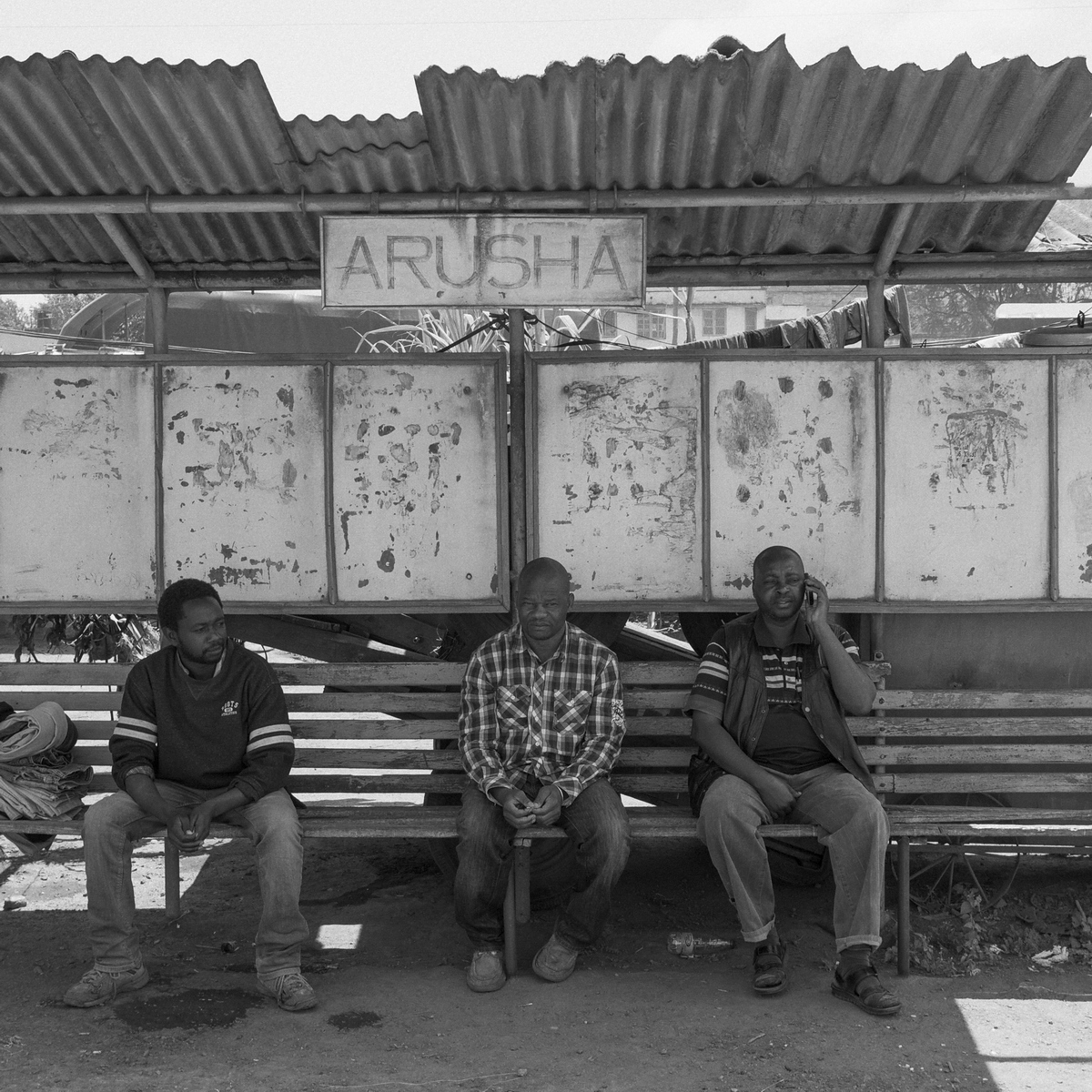

This is the station in Kalávryta (2480 ft altitude). Although in use on weekends, it is pretty quiet and has a lost-in-time look to it. The town is historically noteworthy for two events. First, at the nearby Monastery of Ayia Lávra, Germanos, the Bishop of Patras, raised the flag of revolution against the occupying Turks on March 21, 1821. This eventually led to Greek Independence. The second event is more tragic. On December 13, 1943, German occupying troops massacred 1436 males over the age of 15 and burnt the town (from Blue Guide Greece, 1973 edition).

Here are the young beauties in the old rail car.

Zachloroú is the first stop north of Kalávryta, where many people get off the train and hike downhill through the gorge. In my case, I took a taxi from the coast to this station to begin the hike. The route is part of the E4 European long distance hiking path (if you are really energetic, you can walk the E4 from Tarifa, the southernmost point of mainland Spain, to Crete!). There are two tavernas right at the edge of the rail line. One of them specializes in delicious roasted rooster and local retsina, where you can fortify yourself with calories in preparation for the 4-hr trek. One of the nice things about travel in Greece is that even small rural places prepare amazingly good food. There is also a nice little hotel if you want to stay the night (perhaps you had too much retsina…).

As you proceed downhill, you pass stone work sheds and water tanks, which have been restored and painted. The Ο.Σ.Ε. must have put a lot of money into the project.

All the track was replaced in 2008-2010. From Wikipedia: “The railway is single line with 750 mm (2 ft 5½ in) gauge. It climbs from sea level to 720 m in 22.3 km with a maximum gradient of 17.5%. There are three sections with Abt system rack for a total of 3.8 km. Maximum speed is 40 km/h for adhesion sections and 12 km/h for rack sections.” The total route is 33 km.

The gorge gets more and more rugged, and you wonder how the engineers managed to tunnel and bridge their way up this valley. What ambition. The tunnels are interesting because you need to be sure you are not in one when the train comes. The first time I walked the route in 2008, the system was closed while the tracks were being replaced, but the next time, I had to remember to look for the train. It’s really not a problem except for the bridges and tunnels.

Finally, as you approach the coastal plain, the gradient levels out and you have an easy walk to the depot in Dhiakftó. The geology is also fascinating, and you pass through regions of conglomerate, sandstone, limestone, and alluvial outwash.

At Dhiakftó, the excursion train meets the main Athens-Peloponnese line (also narrow-gauge). A new full-gauge rail is being built to connect to Patras, but I do not know if the new line will come to this rail yard or be routed further inland.

(This is Part 1 of a two part article on the Railways of Greece. Be sure to check back next Thursday for Part 2)

Andrew Morang – Photographs and text Copyright 2016

See more of Andrew’s work at his blog, Urban Decay.