I

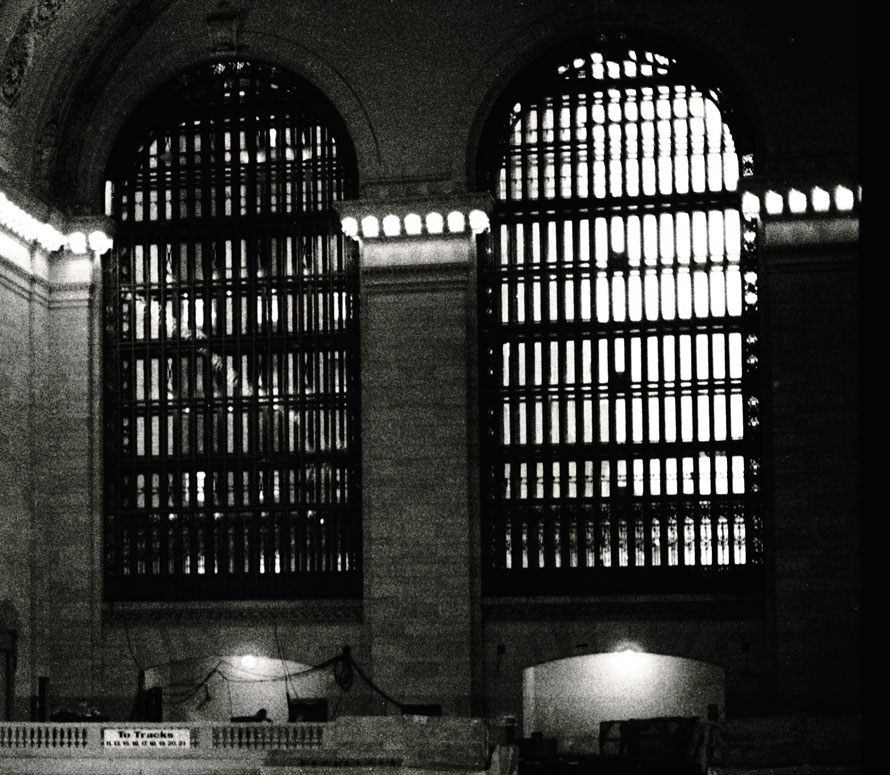

Railroad architecture isn’t only stones and cement, iron and steel, vertical elevations and so on. It’s also the spirit, or as we may say, the ‘atmosphere’ of the place. And equally, it’s the culture of the lives that have used it.

If therefore you wanted to know more about major railroad stations with a long history, you could do worse than listen to the opening clip from a radio program called Grand Central Station. The program was sponsored by the Pillsbury Flour company and it aired until 1954. Every week, the listener was drawn into a world where the railroad and the station building intersected with human life.

Read more