Each year for thirty-five years, I go to Montana to fly fish for trout. Known as the Big Sky Country, it truly is the last best place for such fishing. At this point, you’re possibly wondering why you’re reading a fishing story in a railroad publication and I’ll tell you why. About three years ago, I saw a picture of an old interlocking tower located in Guilford, Connecticut and in studying this picture I noticed a wind-up clock and oil lamps. In a photo taken in the 1970’s, one can see that the board is black paper and at this time electric lights had been added to it like all the towers I’ve previously visited. So, the old picture I saw was before electricity was added to the tower

Back about 1959 or so, my parents were in a car accident and my mother got hurt badly. They had just built our home and my dad had no money for a baby sitter or family nearby so he took me to the tower each day and I sat there for eight hours. When things got back to normal, and because he had Tuesday and Wednesday off, he would take me with him each Saturday because I enjoyed going with him very much and it became our time together. That became our day together until I hired out in engine service in May of 1970.

In all those years and even after hiring out and working forty-two years, I had not given any thought to how the trains ran before electricity and phone lines. It became a real eye opener for me. When information was passed to me from my friend Jon Chase about all the towers along the New Haven Railroad from New York to Boston, I wanted to know more about Morse code as the method of communication on the railroad. Through my quest for knowledge about American Morse on the railroad, I came to know Chris Hausler and a small group of others that helped me learn and understand a great deal about this subject. After several years of friendship, Chris still helps me and this is how some of the information for this story came to me.

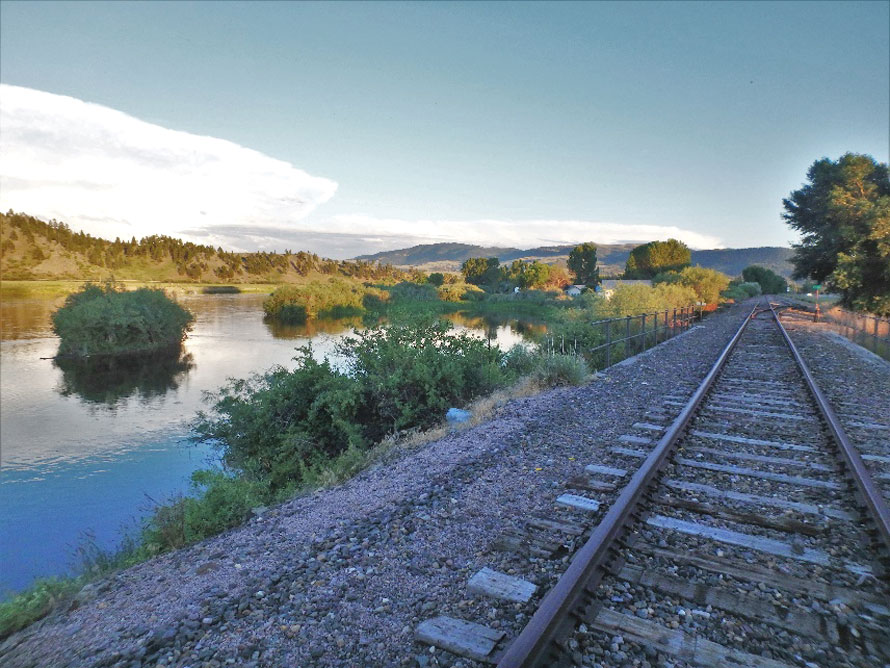

Back to fishing the Missouri River. For many years there was a place I would walk into from the old Great Northern track and I noticed wire lying along the track. Fishermen are used to seeing wire out west because it’s how the ranchers keep their cattle in one area. I always thought that what I was looking at was wire for electric fences. With electricity going through it if the cow touches it, it gets a shock and backs off. But, as time went on and I learned more and saw pictures of the wire used for the telegraph, I realized what I had been looking at all these years.

This summer 2022, I fished in an area I had not been to and while looking at some nice trout feeding, I saw that coil of wire you see in a picture. I had no idea how long it’s been laying on the ground all coiled up but I started thinking about it and with Chris’s help from a list of calls that a past President of the Morse Code Telegraph Club had given him, I can tell you that train orders, the OS’ing of trains, receipt and transmittal of telegrams, and from what I have read in some books, the baseball scores during the World Series, were transmitted by telegraph on this roll of coiled wire. Any members of the Morse Code Telegraph Club reading this know far more than I do about the wire because I’m still learning about the telegraph systems of individual railroads.

To anyone else, you can learn a bit of history along with me on how the telegraph was used to expedite the movement of trains and some other uses. Of course, while fly fishing you spend time waiting for fish to eat and then try to figure out what fly to use to catch them. As I did that and looking at the track as well as seeing that coil of wire, I was certain that I could hear the train dispatcher giving instructions as well as answering the operators at Craig, Wolf Creek and Silver when they would give their OS and report train 235 by them on time. All while I was searching for feeding trout. Then I heard the dispatcher issue the train orders for train 673 a third class Local Freight. out of Great Falls. He was calling the operator’s at Ulm–(M): DS M DS M . . . M DS Q DS Q (Q is Cascade, with a large yard at the station) Q DS . . . DS copy 3 (this would be a 19 order, make 3 copies) the order might look like this:

Order #5 to C&E (Conductor & Engineer) Eng (Engine) 529 Eng 529 run extra Ulm to Cascade.

Then the operator at M would tap out this order for the dispatcher to hear. And, if repeated correctly, the train dispatcher would issue “Com” (complete) and the time at that moment which the operator at M would handwrite in the spaces provided at the bottom of the train order form. If additional train orders were necessary to protect Extra 529 west against any east bound movements coming out of Q, the train dispatcher would instruct the operator at Q to copy seven and the operator at M to copy three, issuing the order first to Q as a restricting order at Q to “C&E westbound trains” and to the operator at M to “C&E Extra 529 west” as a “helping order.” The operator at Q would repeat the order first and the train dispatcher would give a complete time and upon completion of issuance of any other orders for the Extra GN 529 west, the train dispatcher would then issue a clearance card for Extra GN 529 west, listing all train orders (movement and track orders) in effect for the train.

Train order signals at both stations would be displaying STOP prior to initiation of transmittal of train orders by the train dispatcher. Because Ulm would be the initial station for Extra 529 West, that train would likely receive its train orders and clearance at the train order office and enter the main track at the leaving switch of the siding at that station because the train order, as issued, does not entitle the train to occupy main track at Ulm. Upon departure of the markers of Extra GN 529 West from Ulm, the operator would “OS” (report the departure) of the train to DS At that point he would have come back and gotten on the wire M DS M DS…. DS M… Extra 529 West and given the time he departed.

Upon arrival of Extra 529 West at Cascade, the train would not have any authority to the main track at the station and would have to enter the station siding or yard track at the first track switch. Once the markers on the caboose have vacated the main track and the leaving switch is restored to the main track and locked, the operator at Cascade can “OS” (report) the arrival of Extra 529 West to the train dispatcher, getting on the wire and tapping out OS Q OS Q ….. And he would have heard his sounder click out DS Q…. and Q would tap out Extra 529 West arrived at Q at 1050 am. And the wire would go quiet again.

Train 673 had much work to do in Cascade yard as there still stands today tall grain silos for feed for the local ranchers. Upon completing their work x 673 would be fixed up with his orders to run from Cascade to Wolf Creek where he would go in the clear as shown in the employee timetable #19 in effect at that time.

Soon the operator at Silver got on the wire RN DS RN DS…….. DS RN….. And RN would say train 238 Out of Helena OT should we fix him up…… and you might hear DS WC DS WC (Wolf Creek) DS WC DS DS copy 3 and the operator at RN and WC would have their train order pad with double-sided carbon paper ready and again an order was sent over this wire in front of me while I stand in the Missouri River. Order # 6 to C&E Eng 2019 run extra Silver to Wolf Creek and meet #673 Eng 529 #673 take siding. (This is a Timetable meet in Employee Time Table #19 in Effect in 1913). And again these two telegraphers would do a repeat and if it was repeated exactly as given, only then the DS would give a complete time and his initials. The operator at RN would put his semaphore signal to clear and hoop up the order as the train came into their station. At Silver the engineer might climb down from the engine and speak to the conductor and have an understanding of what will happen at Wolf Creek. Upon the arrival of 238 at Wolf Creek at 1221 PM the operator would get on is key WC DS WC DS……. DS WC 238 departed 1221 ready to copy order for X673 the dispatcher would call DS RN DS RN RN DS he would then say Copy 3 and then tap out the order for 673 to continue west from Wolf Creek to Silver.

This happened thousands of times over that coil of wire you see in my picture. The coil of wire became surplus around the 1920’s with the increasing installation of voice telephone train dispatching systems on railroads throughout the Nation. However, for economic reasons, many US and Canadian carriers maintained Morse telegraph systems into the late 1960’s on branch lines and lesser-used main track operations. Even into the mid-1980’s, many Mexican carriers maintain Morse telegraph systems on major main track networks.

I want to thank my first student engineer on Amtrak, Chris Gorick, who gave me the title of this story. Chris Hausler, Don Riser, and Martin Le Roy for helping me so much to understand so much about Morse Code. And Bill Neill, a retired Train Dispatcher as well as former Rules Examiner, for becoming my friend and checking my dictation of those train orders that I could hear while standing in a river and fly fishing in a beautiful place.

Note, so you know, I am not a writer, just a story teller who has had an amazing life because of my parents and my wonderful wife Sandy who has always given me encouragement with anything I do.

John Springer – Photographs and text Copyright 2023