In the forward to his new book, The Railroad and the Art of Place, David Kahler writes ". . . I learned that photographs of moving trains were not everything. Some of the most evocative visual images could be made without rail activity." It is a theme that resonates with the mission of The Trackside Photographer.Jeff Brouws, in his essay which appears in the book (and is reprinted below), discusses Kahler's work in relation to the depression era work of the Farm Security Administration photographers, particularly Marion Post Wolcott, as well as the photographers of the more recent New Topographics movement. With its focus on the visual and cultural landscape shaped by the railroad, The Railroad and the Art of Place holds a unique place in the context of railroad photography, and indeed, transcends the genre. With a broad appeal not only to railfans, but to anyone who loves great photography, this book will find a place in the library of railfans, artists, photographers and historians alike. David has been generous to share his work on The Trackside Photographer in the past, and we are pleased to recommend his new book to our readers.

To Order

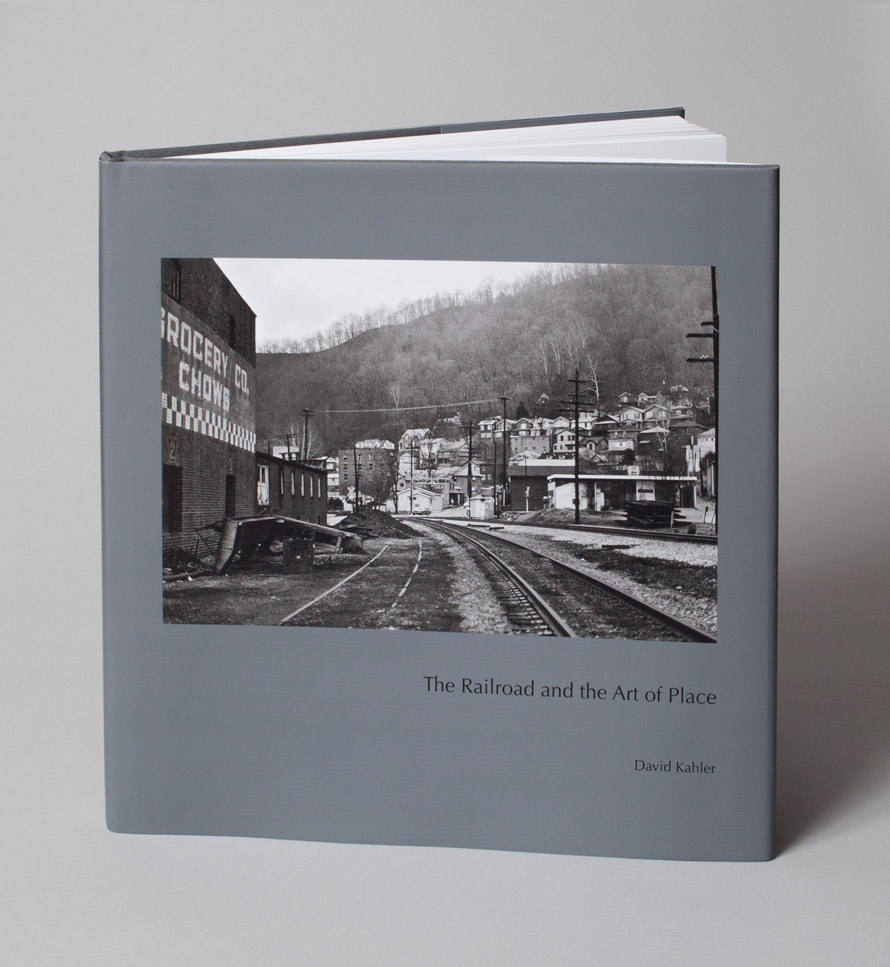

The Railroad and the Art of Place Hardcover, 11x11 inches, 152 pages, Limited edition of 1000. Now available from the Center for Railroad Photography and Art

David Kahler was born in 1937, spending his formative years in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, at the junction of the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Wilmington Northern Branch of the Reading Railroad. Beginning in 1951, he began exploring the railroad environment in the Keystone State with a camera borrowed from his aunt. His interest then turned to the Elmira branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Southport yard in Elmira, New York, where steam was enjoying its last breath. In the late 1980s, Kahler was deeply inspired by an exhibition of O. Winston Link photographs. A few years later, due to that influence, he began making annual trips to the West Virginia and eastern Kentucky coalfields, destinations that strongly resonated with his own aesthetic of “place.” For six years, he and his wife made weeklong trips in the dead of winter to photograph trains along the Pocohantas Division of the Norfolk Southern Railway. Nearly hundred images edited from this body of work form the core of The Railroad and the Art of Place, along with a selection of earlier PRR steam-era images that reflect Kahler’s nascent interest in the railroad landscape. Printed in lush duotone, this 152-page, hardbound, 11 x 11-inch volume also contains three essays discussing the personal motivations, historical context, and aesthetic development behind Kahler’s photography. Book designed and edited by Jeff Brouws and Wendy Burton, with texts by David Kahler, Scott Lothes and Jeff Brouws.

An Edenic Return No Longer Possible

by Jeff Brouws

A framed photograph by Marion Post Wolcott hangs on the studio wall above my desk—an image taken in 1938, near Scotts Run, West Virginia. A string of dark coal cars slants toward the picture’s central vanishing point where another black mass—the familiar outline of a mine tipple situated in the photo’s middle distance—visually anchors the composition. Dilapidated, clapboard-sided, company-owned housing borders and demarcates the right side of the frame. Low, and slightly off-center, a young girl—perhaps 7 or 8 years of age—carries a can filled with kerosene. Slack-shouldered and stooping from its cumbersome weight she wearily heads home as an end-of-day crepuscular light begins to fall.

This scene—a gray, rural tableau ringed by low hills and tinged with a sooty presence—was a photograph shot by Wolcott on 35mm film, atypical for an artist who normally wielded a 2 ¼ or 4 x 5 camera in the field when working for the Farm Security Administration during the latter stages of the Great Depression. As one of hundreds of images made by Wolcott in the border region between Maryland and The Mountain State over a four-day period in September 1938, this picture is a touchstone of the documentary tradition. In understated fashion it captures a “sense of place,” resonates with social history, and is compellingly composed. That it could easily have come from Kahler’s Leica M6 35mm camera is a given, if he too had been standing alongside Marion on this fall evening, so similar are the two photographers aesthetic approaches, interests and viewpoints.

But the comparison doesn’t stop there. The additional constellation of elements found in Wolcott’s Scotts Run photograph also characterize many of Kahler’s best images: in his work we see a broad, perceptual awareness of the railroad environment and how it interacts with human agency, an affinity for detritus and decay without nostalgic overlay, a graphic eye attuned to compositional possibilities, and an abiding interest in the vernacular and industrial architecture that sits astride the mainlines and meandering branch lines he encounters. All conspire to create what Kahler terms “the railroad and the art of place.”

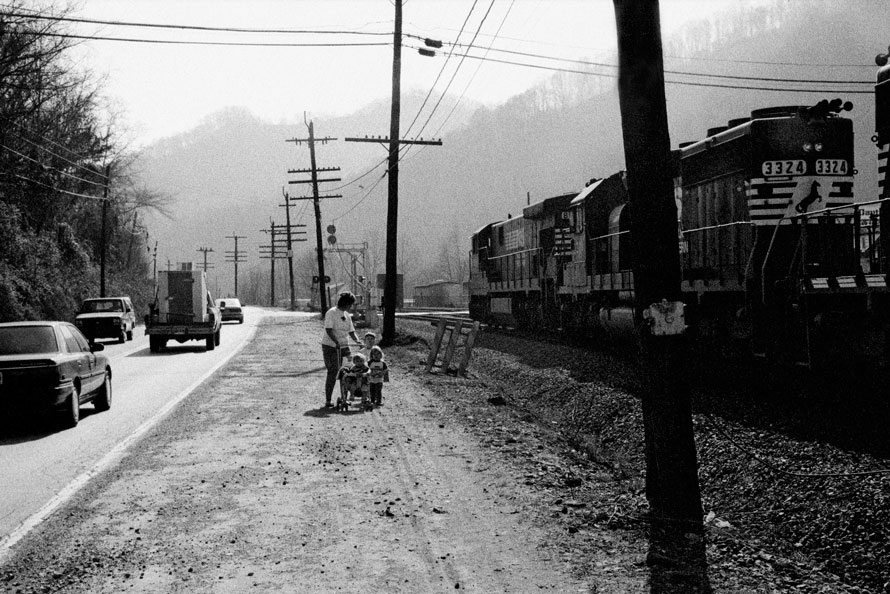

In fact the image David calls “The Sound and the Fury in the Garden” —the title conflating and referencing both William Faulkner’s novel and Leo Marx’s tome on the intersection of technology and nature—echoes and updates Wolcott’s “kerosene girl” perfectly.

In Kahler’s image we see a young, modern mother, presumably without a car or money for gas, walking the mile or two into town for provisions. Pushing a baby carriage with two other children in hand, she traces the well-trod path beside the rail line because it’s the easiest way to get there. Dramatically, unexpectedly, two black behemoth Norfolk Southern diesels roar past with train-in-tow—not unlike the massive coal cars towering over a youngster heading for home in the Wolcott image. While this is Nolan, West Virginia, circa 1992, Scotts Run—as seen in 1938—seems not so distant or different in time, tone, or circumstance. The railroad in both photos dominates the scene—is in fact the main actor on the stage—and simultaneously represents both the constant and change-agent in the garden regardless of era.

As a way of life it scents the air—like coal smoke floating above the hollows on a Sunday morning’s wintery dawn.”

Today, a quiet poverty inhabits parts of West Virginia and Kentucky as it has for the past 90 years. This impoverishment, often out of view, envelops segments of the rural countryside like a slow-growing, intractable cancer. Low-wages and stalled incomes define these places. As a way of life it scents the air—like coal smoke floating above the hollows on a Sunday morning’s wintery dawn. Many of Kahler’s images capture this ineffable mood successfully. The extractive industries have pillaged the landscape in order to feed a nation hungry for energy resources. The railroads, right behind them, have also profited by moving the merchandise to market. In both cases not much of that wealth got transferred to the miners (or train crews) that dug or transported the coal. Aptly, Kahler symbolically captures these hard realities on film; the railroad is seen running through the garden, but is not of the garden.

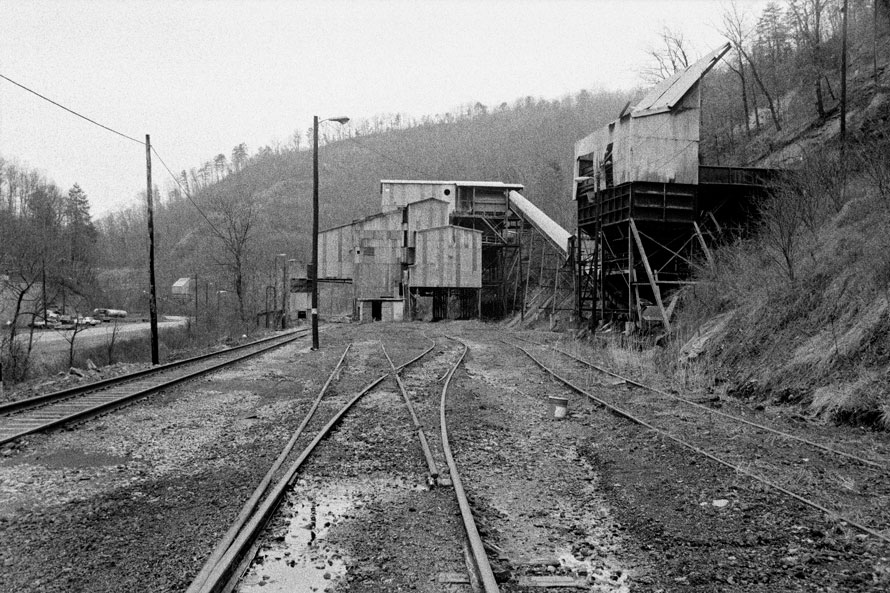

With these thoughts in mind Kahler came to the region in 1992 on an exploratory mission. Searching for photographs along both states’ rail lines—right-of-ways that ran by rivers and sliced through hills, hamlets and villages—he had a feeling that the end was already foretold, the land adjacent to the railroad speaking to him, revealing what was to come. Townscapes and industrial infrastructure seemed worn out, exhausted, and near collapse.

“Creative destruction,” a favorite term of Kahler’s, was manifest everywhere. Paradoxically the chances for evocative photography were plentiful for those attuned to this creeping devolution beside the tracks. To that end, and employing an architectonic approach to picture making, Kahler tends to place aesthetics on equal footing with his subject matter. As a former architect, now retired, how could he not? He sees shape, form and line intuitively and utilizes these formalist underpinnings to transform the physical reality of the scene before him into dramatic and often surprisingly graphic compositions.

This ability to see the “geometry of the everyday” grants him a singular vision. Oftentimes, too, he relegates the train to the background, making it a tertiary figure in the photo—ironically de-emphasized but better integrated into the overall scene. This also becomes another unique attribute of his visual sensibilities.

. . .he created images that withheld no truths, with the roughed up film stock matching the naked and urgent rawness of all he was seeing . . .”

As with Wolcott’s work, Kahler had little fore knowledge of other aspects of contemporary photographic practice or history; he was a neophyte in this regard when he began making his West Virginia photographs as well as the Kodak Brownie images taken in 1957. Yet the aesthetics he chose to employ for both the earlier and later work often foreshadowed or paralleled the photos done by David Plowden, the New Topographic photographers from the 1970s, or Lee Friedlander images found in his book from 1982 entitled Factory Valleys. These artists were front-line witnesses documenting the transformative effects of the machine in the garden but seen from different perspectives. In the case of the Plowden, he caught the final flowering of steam power in America and composed a heartfelt requiem for same; with the New Topographics photographers it was the build-out of suburbia and its impact on the natural world that garnered their attentions; with Friedlander it was the deindustrialization then metastasizing across America’s manufacturing centers in the late 1970s and early 1980s that was subjected to his focus.

Like Kahler, these photographers and movements chose the medium of black and white to tell their stories and did so with acuity. With the same resolve, Kahler compiled his visual record about two railroads—CSX and Norfolk Southern—between Ashland, Kentucky, and Capels, West Virginia, returning yearly from 1992 to 1997. Shooting in gritty monotone, and then purposely intensifying the emotional tenor of his imagery by overexposing Tri-X to enhance the film grain, he created images that withheld no truths, with the roughed up film stock matching the naked and urgent rawness of all he was seeing.

While the hinterlands of West Virginia hold great beauty, part of the state’s geography is also defined by a foreboding abandonment, by a feeling of cultural “left-behind-ness.”

Kahler’s photograph at Iaeger, West Virginia, speaks to these points. Once a bustling terminal site on the Norfolk & Western this image captures this elegiac tone, the true essence of Kahler’s project. While on the surface it could be read as a quiet lament for that which has passed, taken collectively, it along with the other 109 images in this book, conveys something greater—that the machine despoiled the garden and an Edenic return is no longer an option.

Thanks to David Kahler, Jeff Brouws, Scott Lothes and the Center for Railroad Photography & Art for their cooperation and assistance in preparing this article.

Copyright 2016, David Kahler

Excellent!

Terrific essay.