The Great Falls & Canada Railway

In time, the Lethbridge (Alberta district, Northwest Territories) coal mines would feed all the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) steam locomotives in western Canada, as well as the stoves of its stations and many settler prairie homes. The slogan “Galt Coal Burns All Night” was emblazoned on signage wherever it was sold; lumber yards, grain elevators, and farm cooperatives. By 1890, the North-West Coal & Navigation Company (NWC&NC) averaged 90,000 tons delivered per year to Dunmore, and the CPR wanted more. Northwest Mounted Police Superintendent Deane reported the Galt mines could produce more than 1,000 tons per day – with the possibilities for more in sight.

But the CPR was uncomfortable not controlling their fuel stocks. Their eastern operations could easily import cheap Pennsylvania coal to force the Galts’ hand in pricing. What’s more, new mine works were developing in the upper Bow River corridor and the Kicking Horse Pass. In October of 1886, the Canadian Anthracite Company was formed to tap the coal reserves, surveyed a town site near Banff and built a spur line, hoping to market 250,000 tons annually. But the CPR refused the Anthracite bid. CPR president George Stephen cited loyalty to the Galt contract, while expressing buyer’s remorse: “In dealing with Sir Alexander Galt, we departed from sound business principles, and made a contract with him for five years’ supply, and upon terms we should never have thought of … he being the ‘pioneer collier,’ we wanted to get the business started… if we had not done so, it would be a ‘cold day’ now for the Galt coal mine.” Galt was getting $5 a ton at Dunmore Junction for his product, and Thomas Shaughnessy, the CPR’s assistant general manager thought it a bargain: “Even at that price, we were saving very considerably, as all our [Pennsylvania] coal was coming [via] Port Arthur.” But Stephen wanted to grind more pennies out of those five bucks, and to drive Galt’s price down. The answer for the NWC&NC was market diversification; the company needed alternate outlets to justify the Lethbridge operations (and to offset the CPR’s demands to reduce the coal price). Even with modern machinery and a trimmed workforce, Galt knew that he had to look abroad to sell his product. Across the International border, the economics of the state of Montana were driven by the popularity of newly found metals such as gold, silver, and copper, as smelting plants were erected to process the rich ore. “The productive capacity of Montana, per capita, is equal to six times that of the great wheat growing State of Minnesota,” said the Lethbridge News. How much of an industrial leap the Treasure State had on the district of Alberta was incalculable, as evidenced by the $95 million in mineral production in 1889 alone. One would be challenged to count that much cash in all western Canada at that point in history. Additionally, the railroad baron, James Jerome Hill, was a definite factor in the plan to expand south, where locomotives also required coal. As a rising St. Paul businessman, Hill was quick to the art of the deal, acting carefully as one fledgling railroad after another failed miserably in attempts to bridge Minnesota with the west coast. Using the St. Paul & Pacific Railway he co-founded with Donald Smith (a NWC&NC shareholder) as a starting point, he consolidated the remnants of the bankruptcies into the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway (SPM&MR). It was his move to counter the CPR, which he’d so spectacularly exited a few years earlier. Along the way, the Canadian coal from Lethbridge aroused his interest. With the help of powerful Montana business associates, William Conrad and Samuel Hauser, Sir Alexander & Elliot Galt planned a second railway line to take Lethbridge coal to the state capital at Helena, Montana. However, the economic downturn in the United Kingdom hit the investor base of the NWC&NC hard, leaving the Galts to adjust their lofty plan and re-align the route to the ore-reduction plant of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company at Great Falls instead. As Elliott’s talks with the Americans became public, George Stephen, president of the CPR, intervened with the Canadian federal government, invoking the monopoly clause they had against the construction of railroad lines within a thirty-mile corridor of the United States International Border. Ironically, the embargo was ignored when the Dunmore – Lethbridge narrow gauge line was constructed in 1885; that line was slightly north of the border, so no opposition was made. This time, Stephen lobbied to block the charter application for the Great Falls line – twice in 1886, and again in 1888. The CPR overplayed the hand – the influence of the aging Sir Alexander was underestimated, as the wily tycoon rallied allies in Manitoba. Galt won, and in 1888, the Federal government rescinded the border monopoly. In short order, legislation passed the House to incorporate the Alberta Railway & Coal Company (ARCC) on March 20th, 1889, as a separate company, chartered to build from Lethbridge to the United States border, a distance of approximately 65 miles. The new charter included a clause permitting takeover of the parent NWC&NC – insurance against possible bankruptcy, due to the varying worldwide recessions that could affect the investor base of the company.

Wages for construction crews ran at $1.50-$1.75 for a 10-hour day, but the company store mentality saw that out of the weekly wages, $5.25 was deducted for meals, $1.00 for medical fees, and $5 for local taxes!

The AR&CC received a land grant of 413,568 acres (6,400 acres per mile) from the Federal government. This was later reduced by 12,656 acres to satisfy indebtedness on coal lands, giving the Galts control of a total of 1,101,712 acres. More to the mining mission, they had an option to purchase an additional 100,000 acres of coal lands at $10 per acre. The American portion required a second charter, under a third corporate identity as the Great Falls & Canada Railway (GF&CR), capitalized at $2 million, with equipment costs of $4 million. It was incorporated on October 3rd, 1899 to build from the International Border to Great Falls. Interestingly, the original charter called for the construction of a standard gauge railway, but the lower-cost narrow gauge was instead substituted. The charter was passed shortly after in the Montana state legislature. Through an American company, the GF&CR was controlled by Sir Alexander Galt, with virtually the same directors on the AR&CC. The directorship included railroad builder Donald Grant, Samuel Grant, Alexander Kinsman, William Barr and two of Galt’s Montreal colleagues–Walter Shanly, a Member of Parliament, and Montreal financier William Miller Ramsay.

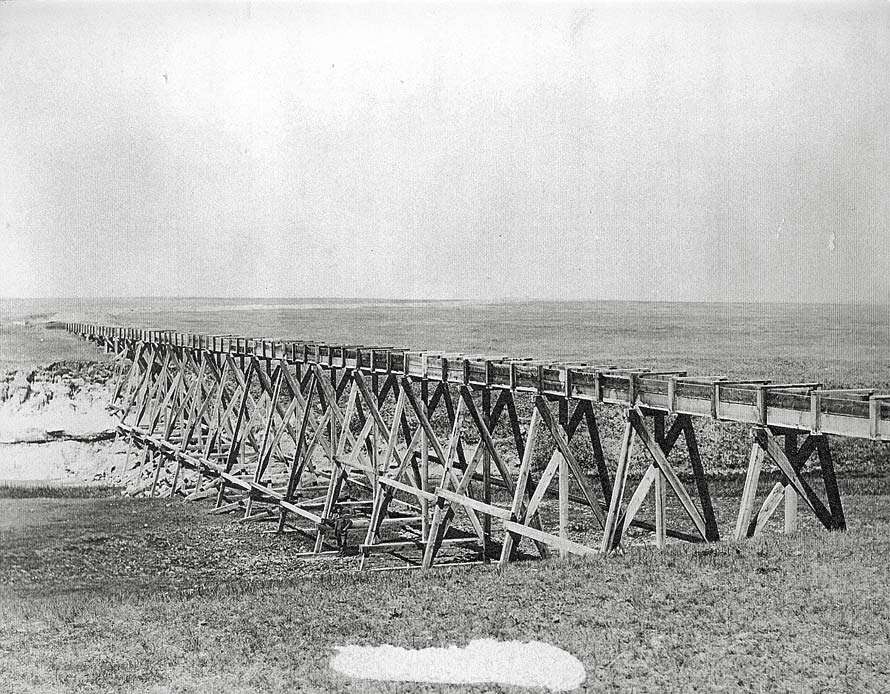

Handled as two separate identities, construction on the twin components of the Lethbridge-Great Falls lines began simultaneously in the spring of 1890. Contractor Donald Grant and partner I.S. Ross were in charge of the 65-mile Canadian route, supervised by P. Egan. Shamelessly, Grant also presided over the GF&CR, where the Samuel Hauser-controlled Fort Benton Construction Company was engaged to develop the 135-mile American section. At both ends of the planned road, carloads of rails, ties, spikes, tie plates, tools, heavy grading equipment, and teams of horses were assembled at the Montana Junction/Ghent switch near Lethbridge, and at the Willard townsite two miles west of Great Falls, where the Montana Central and Great Northern lines met. By April, some 500 labourers were on the payroll, employed grading and laying track on either side of the boundary. Wages for construction crews ran at $1.50-$1.75 for a 10-hour day, but the company store mentality saw that out of the weekly wages, $5.25 was deducted for meals, $1.00 for medical fees, and $5 for local taxes! With mild winter conditions, surveying quickly progressed from Great Falls northward in early February, and grading soon afterwards at the end of March. The grading teams worked far ahead of track layers, with double-bottom plows to loosen the ground, and a pair of state-of-the-art earth-movers working each side of the embankment–each drawn by twelve heavy horses and operated by four men. On a good day, the graders could throw up five miles of rail-ready roadbed. The track-layers were nearly as good, and could install enough ties, rails and spikes to move three to four miles per day.

The 26.5-hour train trip must have seemed like windburn to the many who could recall a three-week haul by freight wagon with the same route”

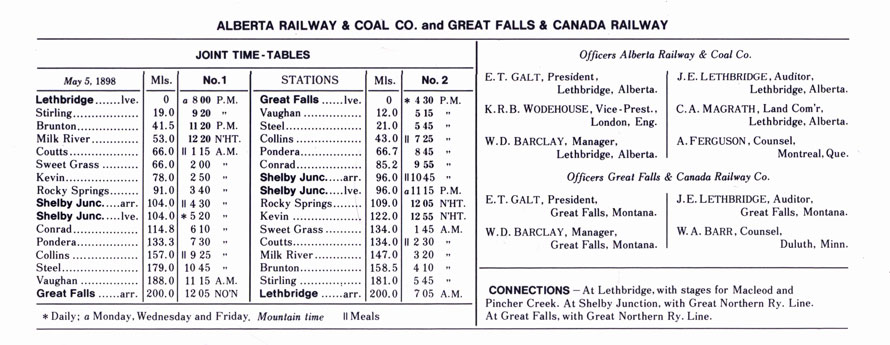

In April 1890 rails were laid down and by June, thirty-five miles were complete, with the graders 80 miles ahead of track builders, the surveyor’s stakes aiming their right-of-way toward the border. On July 1st, 1890, the 36-mile section between Sweetgrass and Shelby was completed, and crews were re-assigned to the section crews working north from Great Falls. Track gangs averaged two miles of track per day, often exceeding 3-4 miles per day. Following a rolling territory of light hills and flat plain, the track took the paths of least resistance, kept grades on the order of 1.25 % and curves with a radius of 10 degrees—all designed to save money on excavation wherever possible. Anticipating heavy traffic, the route planned for five miles of sidings between Great Falls and the border to accommodate parked cars and allow opposing trains to give each other right of way. Such sidings, as well as the voracious need for water led to the creation of more Montana towns where none had existed before. As mentioned in the previous article “Sawed in Two,” the International Train Station was established at Coutts – Sweetgrass and would be the joint station used by both the AR&CC and the GF&CR groups. On October 15th, 1890, the maiden excursion train left Great Falls at 8:30 pm in the evening, arriving at Lethbridge at 11:00 pm the next night. The 26.5-hour train trip must have seemed like windburn to the many who could recall a three-week haul by freight wagon with the same route (or a week by saddle horse). The city of Great Falls reacted in much the same way as the town of Lethbridge had with the arrival of the railway. The newspapers heralded the event and a magnificent dinner was given by Mr. Phillip Gibson at the Hotel Bristol in honor of the GF&CR officials.

That turnaround time spurred a tourism initiative; On October 20th, 1890 a special excursion fare was announced, offering a week long round trip from Great Falls to Banff, via the Lethbridge-Dunmore line and the CPR– at a rock bottom $10 per person. The price of a return ticket between Lethbridge and Montreal was $62.50 in December 1891. On both lines, occasional special trains accommodated charter passenger traffic for holidays or special events. A sporting train ran between Lethbridge and a racetrack on the outskirts of Great Falls for those who didn’t want to tack up their own animals to watch other horses compete. When regular passenger service was established on December 8th, 1890; a traveller could expect a daily train between Great Falls and Shelby, and a bi-weekly schedule to Lethbridge, for $10. With regular service on mixed freight-passenger trains, the 26.5-hour trip was soon cut down to 24 hours, even 17 hours if everything ran right. But even with this miraculous delivery time, a third trip per week between the two cities was not added until 1901. The coal trains hauled 200-300 tons per trip, with as many as four trains per day. Between the International Border and Great Falls was a divisional junction called Virden (just slightly west of present day Shelby), where the GF&CR established a large siding, roundhouse, maintenance shop, and station. The siding’s low elevation made for readily available water, and a coal stockpile was supplied by Lethbridge and fed the locomotives of both the GF&CR and the GN railways. The coaling towers were well guarded, and trainmen learned not to dawdle after filling their tenders. If the train sat too long, fireman Ross Harte claimed that twenty thieves would be atop the car tossing off the fuel. As firewood in the area became scarce, a stockpile of burnable coal was tantalizing to the locals. The GF&CR pursed prosecution wherever possible. At least one thief was brought to trial, and severely fined as a warning to the others. Also at this location, parallel to the standard-gauge tracks of the Great Northern Railway, a massive thousand-foot-long, 26-foot high interchange coal dock was constructed, so that the Galt’s self-dumping narrow-gauge cars could dump their contents into 15 to 20 GN hoppers at the same time. Virden was the location where the Canadian crews would change trains with the American crews; for example, the AR&CC would operate trains from Lethbridge to Virden, and the GF&CR would operate trains from Virden to Great Falls (crossing the standard gauge GN east – west main line through Shelby).

At the GF&CR terminus, where the company stopped short of bridging the Missouri River and running into Great Falls, a roundhouse, and a turntable was established. The Panic of 1893 was a serious economic depression in the United States that was marked by the overbuilding and shaky financing of railroads, resulting in a series of bank failures. Compounding market overbuilding and the railroad bubble was a run on the gold supply. This Panic was the worst economic depression the United States had ever experienced at the time. This Panic would affect most of the railroads, including the GF&CR to a lesser-extent. The famed American railroad, the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad would declare bankruptcy, followed by the Northern Pacific Railway, the Union Pacific Railroad, and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. The prolonged effects of the Panic would also cause banks to close, businesses to fail, and numerous farms to shut down. A wave of strikes took place across the United States, most notably coal miner’s strikes that lead to violence in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois. The more serious Pullman Strike would virtually shut down all the railroads in the United States west of Detroit, Michigan from the spring to the fall of 1894. The American Railway Union fought the Pullman Company, several railroads (including Great Northern), and the federal government over massive layoffs at the Pullman company and the general reduction of wages throughout the railroad system. At its peak 250,000 in 27 states were on strike – and 30 strikers were killed in response to the riots and sabotage that caused up to $80 million in damages. The violence occurred when the federal government sent in the Army to stop strikers from interfering with trains that carried mail. However, as this was occurring the GF&CR was unaffected by the strikes and was for the summer of 1894 the only source of railroad communication open to Great Falls. As a result, the GF&CR put in special freight rates from St. Paul, Minnesota over the lines of SOO, CPR, and their own AR&CC to move items to/from Great Falls. Ironically, some of these freight rates were lower than what Great Northern was charging prior to the strike! In July 1894, surveyors were busy locating a grade for a new branch to the Boston & Montana Smelter and the citizens of Bynum, Montana were clamoring for a 16-mile railway line to their town. Plans were being prepared for a new $5,000 GF&CR station at Great Falls, to be built just west of the Montana Brewing Company’s plant. The tract of land was to have been about nine acres in area, accommodating a yard 2,000 feet long and 200 feet wide. The right-of-way, coming in from Willard, was to have been 50 feet wide by two miles long. All this enthusiasm had been generated by the recent discovery of anthracite coal in the Crowsnest Pass and vastly increased tonnage on the GF&CR was anticipated. And with good reason: Pennsylvania anthracite was $18.00 per ton in Great Falls, while the Alberta fuel was expected to sell for $10.00. Alas the best planning did not achieve the anticipated result… In 1895, the Montana state Board of Equalization, assigned to find new revenue for a growing state, looked at the GF&CR’s corporate structure, and apparently weren’t satisfied that the railroad was American enough in its ownership. It assessed taxes on the road at a crippling $2,500 per mile. Elliot Galt appealed, but the “Equalizers” remained unmoved. Then on December 27th, 1895, a passenger coach on the Lethbridge train derailed and burned. The Railroad blamed the wind which was quite blustery that day. A month later a Mrs. James Pierce and her three children filed a suit for $60,000 against the GF&CR, the plaintiff charged that the rail was defective and a wind could not blow the coach over. “This was the largest suit filed in the county up to that time.”

But the writing was on the wall for the Canadian coal imports. In May 1896, the Galts exclusivity ended when coal deposits began to be exploited at Sand Coulee, in Cascade County, just seven miles from Great Falls. The GN quickly purchased the coal mine and delivered local product to Great Falls at $2.50 per ton, undercutting Galt’s coal by 50%. Suddenly the bloom was off the rose; the American market dwindled, and with it, the GF&CR’s main reason to exist. Further speculation around town was that the GF&CR might soon be sold, or parceled off. An unsubstantiated story had Elliott Galt selling off four locomotives to a speculator in Alaska, and that eighty miles of track were going to be pulled up and shipped to the far north for use of a railroad in the Klondike. All of those reports proved to be false – just so much gold rush rhetoric. In the early part of 1897 the Railroad made a surprise move. According to the Great Falls newspaper, “The Great Falls and Canada Railway recently filed an application at Washington to become a bonded road. It has been approved by the Treasury Department. It is hoped the line is changing to standard gauge and will have through access north & south, and a possible connection to the Burlington Railroad construction from Great Falls to Billings.”

But a bright light was on the horizon – as mentioned previously, the federal government granted AR&CC (and its predecessor NWC&NC) large tracts of land (in excess of one million acres) in return for building the rail lines (from Dunmore to Lethbridge and Lethbridge to Great Falls). Land sales would offer profit back to the AR&CC, but the AR&CC needed people to buy the land and farm. But on the semi-arid prairie, irrigation would be the key to keep people on the land. Irrigation was proposed back in 1881 by William C. Pearce, a senior federal civil servant in Calgary, after a study of systems in Colorado and Utah. The only people with the extensive knowledge of irrigation at that time were the Mormons, based out of Utah, USA. In negotiations between the company and the Mormons, it was decided that the AR&CC would sell the land to the Mormons for $1 per acre, on the basis that the Mormons would dig an irrigation canal. However, two obstacles came up; the first was the church did not want to assume the whole burden of the project, and the custom of granting alternate sections of land prevented efficient irrigation, because they would have to dig the canal through government, school, and private lands as well as their own. The deal was put on the back burner for a few years, while talks continued. After the federal election of 1896 Clifford Sifton, the new Liberal minister of the interior, became involved with the negotiations and offered assistance to speed up the processes. The minister worked with the Galts’ land commissioner, Charles Magrath, and the lobbying efforts of the Lethbridge News, to allow the AR&CC to consolidate its land holdings into large blocks, and assisted with the necessary survey and research work into where the proposed irrigation canals were to be built. Again, the AR&CC re-approached the Mormons and this time was able to work out a suitable agreement. The Mormons would supply all the labor to build 100 kilometers of irrigation canals from the St. Mary’s River, in return for a payment of one-half in cash and one-half in land with the water rights included. As well, the Mormons were to establish two settlements with 250 inhabitants in each (future Stirling & Magrath). With the deal signed on November 3rd, 1897, the Mormon leader, Charles Orca Card, plowed the first furrow for the irrigation canal ten months later. The GF&CR gained its new form of railway traffic – transporting Mormon settlers north from Great Falls into southern Alberta. The railway would lessen the new settler’s feelings of isolation from Utah, and speed up the colonization of the AR&CC owned land.

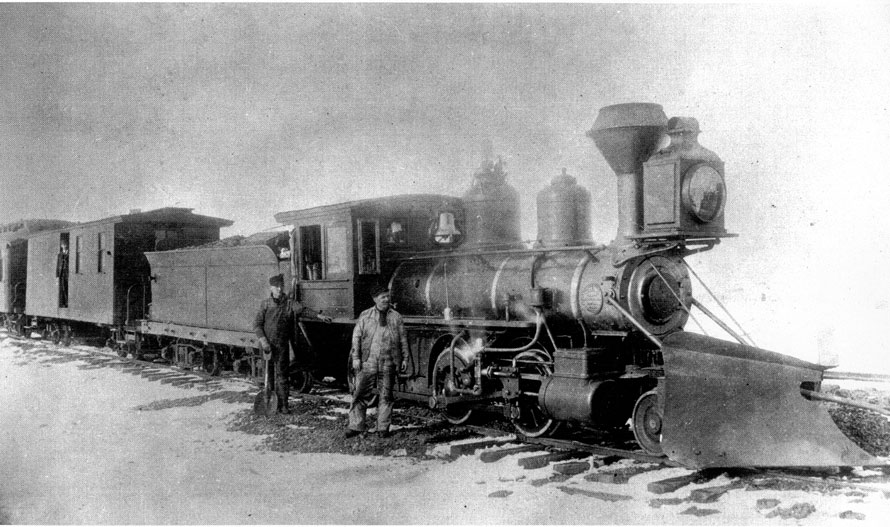

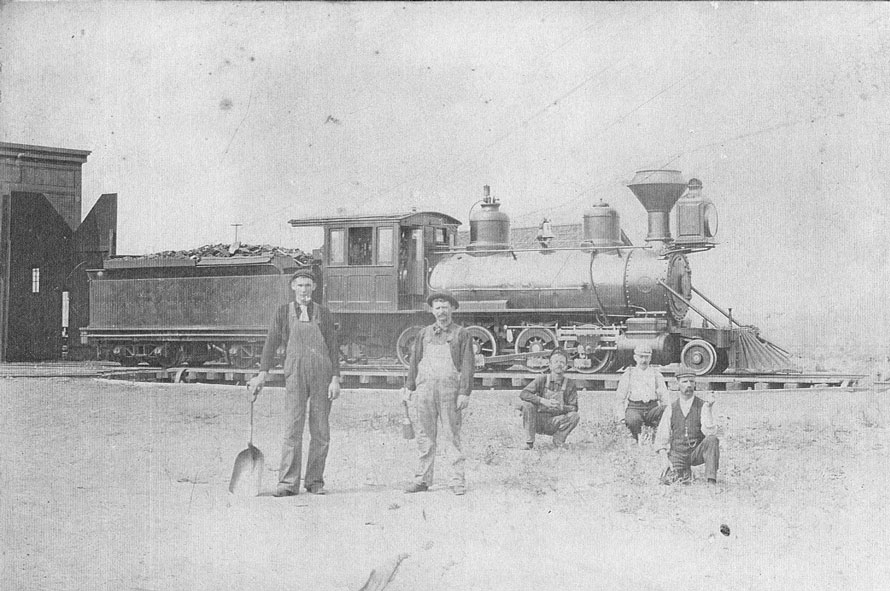

With the Lethbridge – Dunmore line being upgraded in 1893 to standard gauge (as part of the lease agreement with the CPR), the remaining narrow-gauge engines were transferred to service on the Lethbridge – Great Falls line. Seven of the original Baldwin 2-6-0 engines, were converted into “Consolidation” units, adapted for dual gauge usage. Eventually two of the Baldwin Moguls were deemed surplus. In the summer of 1895, the AR&CC Engines Number 13 and 14 were sold and moved to the Kaslo & Slocan Railway (KSR) in the Slocan mountain range of British Columbia’s West Kootenay region – and renumbered as KSR Numbers 1 & 2, respectively. Number 1 was retired in 1908, while Number 2 was used by the CPR in converting the KSR to standard gauge. Both were scrapped in Vancouver in 1917 to meet wartime steel needs. On a side note, two of the former Galt locomotives (NWC&NC #6 & #7) were used on the construction of the CPR Spiral Tunnels by Field, British Columbia by the construction firm of MacDonnell & Gzowksi in the early 1900s. After construction of the tunnel, #6 was shoved over the side of the mountain and its remains still exist today. A person can hike up to them and look at them! In 1901, Elliot petitioned Ottawa to amend his charter to allow him to lease the Lethbridge – Great Falls line to the CPR, on both sides of the border. As that was being reviewed, Elliot left for England to seek the shareholders’ blessing to upgrade the line to standard gauge, creating a more reliable product for the potential sale. Elliott publicized both ideas widely, but should either ploy fail, there was the rumor of pulling up the tracks and selling everything to the Alaskan speculators. The idea of CPR controlling the line from Lethbridge to Great Falls concerned James J. Hill; wary that Galt’s CPR alliance might bring his hated competitor virtually to the Great Northern’s turf and doorstep. Galt’s rumor mill worked! His stories designed to motivate Hill into action, enticed his GN to purchase the American portion. The ploy worked, and Hill recognized a threat when he saw one. The CPR-controlled St. Paul & Sault Ste. Marie Railway (the “Soo Line”) had already penetrated his perceived regime in the northeast. Hill got his lawyers into action quickly, and incorporated the Montana & Great Northern Railway (M&GNR) on June 6th, 1901, a new group to build branch lines and a telegraph system for Great Northern railway in Montana. One of the objectives of the M&GNR was to purchase the GF&CR assets. Within months of the incorporation, Hill was poised: “The recently incorporated Montana and Great Northern will enable the Great Northern to shut out all competition in northern Montana, unless other systems desire to build parallel lines.” What may have surprised the officials of the Great Falls and Canada was the purchase price – apparently, Hill paid only $750,000 for his new property (payable to the Bank of Montreal in New York City), but simultaneously assumed indebtedness of $2 million, most of which was held by a New York City bank (which would be paid off by 1922). The Montana and Great Northern was not to assume control of the property until October 30th, 1902, thus giving the GF&CR time to upgrade the line to standard gauge. With the sale agreement came the joint use by both M&GN and the AR&CC of the Coutts-Sweetgrass International Train station. As soon as the sale agreement was signed, the AR&CC installed a third rail on their line from Lethbridge to Coutts to be able to bring up the narrow-gauge locomotives and rolling stock from Montana, but also to service their narrow-gauge track from Stirling west towards Cardston. In the spring of 1902, heavy rains caused severe flooding and innumerable washouts, with several major bridges on the line from Great Falls to the International Border being swept away by roaring streams. The M&GN closed the line to traffic, and rapidly undertook a $2.8 million-dollar upgrade program to replace bridges and culverts, relocate portions of the line to reduce the curvature, improve the grades as required, and upgrade the light track iron with heavier rails. On January 1st, 1903, standard gauge service commenced between Lethbridge and Great Falls, Montana. Ironically, the M&GN was merged into the Great Northern family on July 1st, 1907.

While a narrow-gauge railway had at first appeared to be a viable enterprise to the Directors of the AR&CC, it had some negative aspects. At a time when most railways in North America were building to a 4-foot-8 1/2-in standard gauge, Galt and his associates chose to build to the less expensive 3-foot narrow gauge. They saved on the main line costs, but spent much more on expensive freight transfer facilities, necessary wherever the narrow gauge touched the standard gauge. Moreover, the AR&CC/GF&CR had been built primarily for the purpose of hauling coal and little effort had been made to diversify its traffic into general merchandise until it was too late. The final blow was dealt when the Montana Sand Coulee coal mines began to produce. This destroyed the GF&CR’s main source of revenue and, to economize, the railway deferred equipment and right-of-way maintenance, a decision that resulted in rapid deterioration of the plant that rising profits could not forestall.

Jason Sailer – Text and photographs Copyright 2017

Jason, this is a great historical article, can I have your permission to republish this in the NMRA British Region Roundhouse?

Hi Peter, sorry for not seeing this sooner. If you are still interested please let me know and we can arrange something. Thanks

Jason, I am the great granddaughter of Thomas Nolan, the engineer in the third picture in your article. This is an excellent historical article and I would like your permission to include some of it in a family history that I am currently working on with my two sisters.

Beverly, I have emailed your comment to Jason in case he does not see this and you should be hearing from him. Thanks – Edd Fuller, Editor

Thanks Edd, much appreciated

Jason, this article is so full of wonderful history. I am currently researching my grandfathers trip west through Canada and then his first few years in Montana. I do believe he may have worked on putting in the narrow guage between Great Falls and Shelby, MT. What would I have to do to get a copy of this to add to our family history that I am compiling?

Hi Christine that is very cool. If you want to email me or message me on my photography facebook page (Jason Paul Sailer Photographics) I can get you a copy of this. Thank you