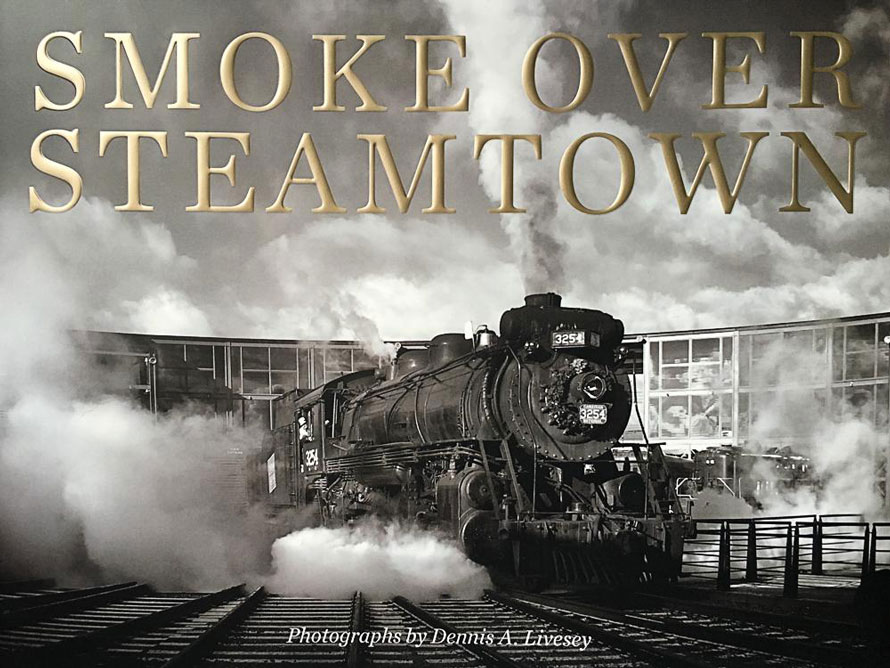

Dennis Livesey in the last few years has become a well-known and respected railroad photographer. His new book Smoke Over Steamtown was published to critical reviews in Railfan & Railroad, Railroad Heritage and on Amazon. The book is available at Ron’s Books, Amazon and other fine booksellers. Shortly after the book was published, Livesey’s photographs were introduced to the general photographic community on the Photo District News website as their “Photo of the Day”. His first art gallery show, “Echos of Steam” is on display at the Valley Railroad’s Oliver Jensen Gallery in Essex, Connecticut until 10/22/2017. In conjunction with that, The Friends of the Valley Railroad elected to use 15 of his photographs for their “Railroad Calendar 2018.” His second gallery show, “Smoke Over Steamtown” is on display at Steamtown’s Visitor Center in Scranton, PA until 3/3/2018. Closer to his home in New York City, he has three images with the New York Transit Museum’s Grand Central Annex exhibit “7 Train: Minutes To Midtown.” His work has been recognized by the Center for Railroad Photography & Art’s John Gruber Creative Photography Awards Program since 2013. Frequently in Railfan & Railroad and Trains magazines, his most notable article was “Transitscapes” in Railfan & Railroad’s August 2015 issue featuring his exploration of the New York City rail scene. Lastly, he was just awarded the Grand Prize in Trains Magazine 2017 “Lucky 7” Photo Contest.”

We recently talked to Dennis about his career in photography and his love of railroading.

Edd Fuller, Editor, The Trackside Photographer – Dennis, it is a real treat to have the opportunity to talk with you about your outstanding work. I suppose the place to start is with your love of railroads. How did that come about?

Dennis Livesey – In 1954, on one winter evening just after sunset, with red-gold light coming through the silhouetted bare trees and the cold nipping at our noses, my mother pulled me out of our ’47 Plymouth maroon woody station wagon. We were at the New Haven Railroad’s Mamaroneck, New York eastbound platform near one of the company’s characteristic New England brown-on-tan saltbox canopies. Holding me on her right hip, smiling with her blue eyes flashing, she pointed to my right and said, “Look Dennis, look! It is the train bringing Daddy home from his job in New York City!”

I looked at her, phlegmatic like any toddler, not a wit of comprehension coursing through my brain. She said again, “Go ahead! Look now Dennis!” Finally I caught on and turned in the direction of her pointing hand and saw for the first time in my little life, an object of indescribable wonder.

It was a New Haven multiple unit commuter train. I cannot recall at this remove if they were the “old” Osgood Bradley MUTs or the “new” Pullman Standard 4400 stainless steel “washboards.” All I do remember is that I was looking at something that was almost as big as our house, with even more windows and doors, all the while it was MOVING.

The whatchacallit, (a train?) was slowing down and even before it stopped, men started stepping off the stairwells. They were all dressed in the same manner against the winter chill in heavy toggle beige coats, fedoras, gloves and briefcases. There were some women too in dark wool business dresses, thick coats of wool or fur, with funny shaped hats defying description, wearing dark high heels and nylon stockings.

This crowd of strangers turned into a tsunami and they seemed to be all coming at Mom and me. I was getting scared but wait! Is that? Could it be? Yes it is! Coming through the crowd was the beaming face of my Daddy!

He joined his reception committee, gave Mom and me a big kiss, then hustled us off to the Plymouth and home .6 miles away. I didn’t know at the time where this adventure that is railroading would take me. All I can say now is that I am forever grateful to my parents, Jane and Herb, showing me this world.

Edd – Do you remember your first attempts to photograph trains?

Dennis – Dad was the family shutterbug dutifully recording the family events. This considerable action of cameras, albums and Kodachrome slide shows bit my interest hard. My first Lucius Beebe book was given to me by Dad who had seen, perhaps even met, Beebe. Dad’s photos and Beebe’s book made me a sponge for images, any image. I wanted them all, books, magazines, TV, movies anything that was a photograph. Adding to this, my brother Bailey was a college art student so I was surrounded by images.

Dad, when I was five, let me take my first shot. It was of our new Buick. I can say at least it was a ¾ wedgie on the fireman’s side. I was given a fine Kodak folding camera when I was 6 but it broke rather quickly in my childish hands. It was not until Christmas 1960 that I got a solid, unbreakable plastic Kodak Starmite which was to last me 10 years. (Built in flash bulb holder! Two apertures! One shutter speed!).

With the Starmite’s genuine plastic lens I took my very first train picture. And not just the MU’s or the freight trains of the New Haven, but a full-bore 4-8-4 steam locomotive, Reading No. 2124. It was taken on June 11, 1961 in Port Reading New Jersey at the beginning of an Iron Horse Ramble. I was 10 years old.

Edd – From there you went on to a career in photography as a cinematographer. Tell us a little about how that came about. How did your work in film influence your still photography?

Dennis – Besides trains and photography, growing up I also loved movies, rock music and the theater. In school, I had a working rock band, leads in school plays, a school radio DJ show, had my photos in the yearbook plus on exhibit in the school library and I made some Super 8 films. The films I made in college sophomore year. I enjoyed that tremendously. So thinking about it, I couldn’t see a career as an actor or a musician, but I could as a movie cameraman. After graduating NYU Film School, I was a motion picture camera assistant for about 35 years. From Hollywood to New York, I did mostly workaday film work but on occasion, did do projects where there was beautiful lighting, creative composition, with all the movie crafts coming together to create magic. At times, it was the greatest school and experience I could ever have. (In the movies, it is all about the credit. See mine here. (http://imdb.to/2wnsk8t)

A few years ago, Bob Lyndall, Eric Williams and Travis Dewitz, in a short period of time, all told me separately that they saw cinematic influences in my work. This was eye-opening for I had never looked at it that way. Looking back on my photos, yes, I now see the influence. (Who am I to argue with these talented men?) I am very grateful to my friends because it has helped me codify my approach. That approach would be: I wish to make the most vivid, emotional and cinematic image I can. I then look for the most dramatic, contrasty, chiaroscuro light with bold color that I can find.

Edd – You use color in your photographs exceptionally well. While digital processing offers unprecedented control over color, it is an area that is difficult for many of us to come to terms with. Would it be safe to say that this sensitive use of color is to some degree a carry-over from the craft of the cinematographer?

Dennis – Thank you for that. But I must say I feel this is ironic because I never thought my color touch was sensitive. In fact, I feel guilty about how ham-fisted I am with it because I think I am as sensitive with color as a 4-8-4 locomotive is to 70 lb rail. I hammer, crank, I explode my color. Too much is simply not enough. I want that color to send shivers down spines.

Edd – I meant “sensitive” not in the sense of being delicate, but in the sense of being aware of and open to the expressive capabilities of color. The term “ham-fisted” might describe the garish HDR color that is seen so often today, but in my opinion, there is nothing ham-fisted about your work.

For example, in one of my favorite photos you use a limited palette of blues and grays with accents of yellow/orange, and the color creates the mood very effectively. I can feel the damp and smell the coal smoke. Tell us a little bit about how this picture came about.

Dennis – In every endeavor, you must learn and you must continue to learn your craft and your tools. In photography, your camera is first. Learn every button, dial, lever, menu item of the device. Learn that camera so well that it becomes invisible. This must happen because you have to shoot through the camera, not behind it.

The same goes for processing. You must take the bull by the horns and learn your processing program. Again learn what every mode, every panel, every slider, every adjustment tool does. You must be in command. When that happens, you are liberated and can soar.

This leads to the image I call “End of the Run.” Here you see Valley Railroad engineer Ken Blandina heading back to No. 3025 so that he could put the locomotive in the barn. It was overcast, lightly raining, and the sun was behind the clouds making the illumination low and soft. My processing process is such I look at the image, give it basic exposure, color, level and cropping. Then with this particular image I started to play aggressively with the highlights, shadows, whites, blacks, clarity and vibrance. This was the result that came back at me and it was because I had new confidence in my processing. I was pleased, for it has a Tim Burton-Halloween movie look. Someone made the wonderful comment that the leaves look like flecks of gold.

I wish to make the most vivid, emotional and cinematic image I can.

Edd – Among railroad photographers, whom do you most admire? Who inspires you?

Dennis – I have been admiring so many photographers for so long, any complete list I make will take us into next week.

I’ll break it down to three generations. I was first inspired by what I call the “Holy Trinity Plus Two” of Phillip Hastings, O. Winston Link, David Plowden, Jim Shaughnessy and Richard Steinheimer. Their stunning compositions and heartfelt humanity are the measure all photographers should aspire to.

The next generation took up this mantle of humanism and context and bent the rules some more. John Gruber’s photojournalism, Mel Patrick’s nocturnal inventiveness, Victor Hand’s audacity, and Ted Benson’s passion.

Today’s generation, further bending convention, is probing the outer limits of what train photography can do. Mitch Goldman is the panmaster, Joel Jenson has heart-breaking soul, Travis Dewitz knows where the unusual is, and Eric William’s takes framing were no one has gone before.

I must include my favorite lesser talked of shooters: Jim Gallagher and his inventive composition in the steam/diesel age, John Krause’s clear narrow gauge views, Don Ball for showing how it was possible to reject the wedge, Robert Hale, the original panmaster, and George Hiotis, the best photographer most people have never seen.

Edd – Are there photographers not normally associated with railroading that have influenced your photography?

Dennis – It is incumbent for any artist to look beyond the genre they are in. Don’t just look at other rail shooters, look for inspiration in other fields. As photographer Jay Maisel says, “If you want to make more interesting pictures, become a more interesting person.” I would count Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Bernice Abbot, Vivian Maier, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alfred Eisenstaedt, W. Eugene Smith, Yousuf Karsh, John and John Paul Caponigro, Gregory Crewdson and Joel Tjintjelaar as artists that expand my mind. Don’t let me forget painters like Jackson Pollack, William Turner, Edward Hopper, Rembrandt, Reginald Marsh, Ted Rose, and Adam Normandin as all affecting how I see.

Edd – Let’s talk about your book “Smoke Over Steamtown.” Tell us how this project came about.

Dennis – I have been going to Steamtown since they were in N. Walpole, New Hampshire and Riverside, Vermont in the 1960’s. I particularly enjoyed a cab ride Dad wrangled for me in the Rahway Valley No. 15. Life got in the way so I was not there for another 16 years until the 1981 Railfan weekend with Don Ball and Jim Boyd. In 1995 I was at the opening of the present Steamtown in Scranton.

Then came January 17th, 2009. Steamtown was doing an unusual winter run and boy, was it winter! It was 10 below with crystal skies and snow on the ground. When I found No. 3254 doing its brake test on the South Ash track, the light, the snow, the smoke, the steam made a combination that was utterly incredible. Few are the times have I have experienced such excitement while looking through a viewfinder.

But things didn’t really hit until I got home and processed the images. For the previous few months, I had been using Apple’s Aperture program timidly. This time I was a little more aggressive, tried a B&W conversion and BAM! My dropping jaw broke the computer table. This was for me, after decades of taking train pictures, (some of them pretty good, some we won’t talk about) the first time I got in the final image what had been in my head and heart. Immediately my brain went back to one of my earliest and most favorite B&W steam images, Jim Shaughnessy’s Canadian Pacific 2-8-2 double header pulling away in Lennoxville, Quebec, 1956. [http://rlhs.org/Publications/Quarterly/PDF/nl28-3.pdf – See Plate 22 on Page 19] Jim’s was an image I loved as a boy and finally, I got an image that was good enough to pay homage. I even got to tell Jim that in person.

I had read many times that rail photographers made it a point to send photos to train crews. I had never done so but I felt so strongly about this image, I sent copies to “The Ice Train Engineer, C/O Steamtown.” That is how I met Engineer Arron Stout. He was the one who encouraged me to volunteer.

The results changed my life.

Edd – You became involved as a volunteer, and worked alongside the crews that maintain and operate Steamtown National Historic Site. You were not only an observer, but a participant. How did your active participation at Steamtown affect your photography? Without this level of involvement, I suspect Smoke Over Steamtown would have been a very different book.

Dennis – Not only different, I think the book, had there even been one, would have been the much poorer for it if I had not been a volunteer. The truth is the experience profoundly affected not only my relationship with railroading but it changed my life in ways I could have never foreseen.

It can be broken down to three things. 1. It answered my question of what is was actually like to be a railroader. This was huge. 2. I had full access to non-public areas enabling me to get on the roundhouse floor, the shop, occasionally the cab and get angles I had never, ever had access to before. 3. I had never known railroaders in my adult life. Now not only did I go to Steamtown to see steam, I went to see my friends who ran steam trains!

After a while of being at Steamtown, I started taking pictures. When my wife and creative partner Mel saw them, she said, “These are good. You ought to make a book.” My inspired, learned response was along the lines of “Whaddyanuts?” In point of fact, Aaron and I had talked about a book but, like with Mel, I didn’t think of it seriously. But with Mel’s persistence, I started to put one together. The book is the result of my sticktoitiveness and Mel’s vision. (That whole effort of publishing in today’s world is a story for another time.)

Let me expound on the number 1 reason stated above: being a volunteer meant I got to learn how to do really cool things, things I had always wanted to do like throw a switch, signal an engineer to stop his locomotive on my command, to operate a 90’ turntable with a huge, hot steam locomotive on it, to help passengers on/off cars and to say “Tickets please!” I got to interact with the public with the kids being particularly gratifying. To realize that while railfans only care what the train looks like, the railroader only cares, “Will this thing make it to the end terminal?”

Ironically I got some railfan comeuppance. Since the tables were turned, I now had to look out for bad, unsafe behavior of the general public and railfans. Fortunately, true danger has been rare but still a constant concern. However, the funniest thing is now I see railfan cameras pointed at me! Ha!

But the most important realization was this, I found out WHY people go railroading. They go in spite of the difficulty because in the end, it is the satisfaction of a team job well done. There have been times I thought I was crazy spending so much time and money at Steamtown and I would be slow to go. But once I got there, and I put on my black/white/gold uniform, did the morning meeting, helped assemble the train, helped spot it for passengers, helped load them on, then checked with the dispatcher, checked my 992B Hamilton [The 992b is a pocket watch that was approved for railroad service, considered by many to be the epitome of the “railroad watch” – Edd], called “All Aboard,” then hopped on, radioed the engine, “NKP 514, ready to highball east” and with that tug, and the ground moving beneath me, the air crossing my face, THIS was the moment that made it all worthwhile and why I kept coming back to this fountain of youth.

Edd – I am sure that being part of the crew opened many doors. Many railroad photographers neglect taking pictures of railroad people because they find it uncomfortable, or they just don’t quite know how to go about it. One of the great strengths of your book is the wonderful portraits of the men and women at work. What advice can you share to help photographers bring more of the human element into their photography?

Dennis– The answer as to why this project worked as well as it has comes down to one thing: intimacy. I was a part of the experience and part of a team running a train, with hundreds of people in our care, safely up and down a mountain. In time the crew saw I was safe and reliable. Now they not only knew me, they had worked with me and I was no longer just some foamer with a camera but a colleague. And this went both ways. I now knew them and cared about them for they were not just some anonymous railroaders. Some of these folks will be life-long friends. It comes down to not just taking a picture of some railroader, it is of someone I respect and care for.

Edd – You must have had some interesting experiences during your years working on the Steamtown project. Is there a story that stands out in your memory?

Dennis– I have mentioned the big things, so here are few other highlights. In prep for a Railfest a few years ago, we had to take Reading No. 2124 from the shop track and spot it to the Diesel Sand track. No. 2124 had just finished it’s asbestos abatement project, had been reassembled, and it had a new very shiny black paint job. I was on the ground with several others as we nursed No. 2124’s huge 220 tons, through tight yard switches and boy, that track did protest! Still, the great moment was when I was walking beside those huge 70” drivers and I could see them move for the first time since June 11, 1961.

My first steam cab ride was at Steamtown Riverside in Rahway Valley No. 15. Now 50 years later, I still can see her. (And sneak a sit in the fireman’s seat again.)

Another moment was when the “Lackawanna F’s” had just come on line and I got to ride the cab of an F for the first time. From that cab I could see, and hear, the Delaware-Lackawanna Alco’s chugging out of town.

Another time, we were doing a trip to the Gap. We dropped all the passengers at Gap station so they could go downtown and enjoy the Founders Day festival. To switch ends with the locomotives, we had to go several miles east to Slateford Junction where the engines could run around. Well, I volunteered to ride the EB trip on the rear end. Normally, this is just a vestibule on a CNJ commuter coach. However, the end this time was the Lehigh Valley Railroad observation business car. So I got to ride, all by myself, on a soft, plush couch in air-conditioned comfort the entire length of the lovely Delaware Water Gap. For a half hour, I was a railroad tycoon!

It was all in that voice sounding like railroad ballast and the magic of hearing it the first time.

I must mention engineer Bernie O’Brien.

When I first started working at Steamtown, I heard the name Bernie O’Brien spoken in almost reverential tones. I imagined someone the size of Paul Bunyan. When I first saw Bernie and saw a very short man, I thought, “THIS is the guy?”

The first time I worked with him, I was riding the fireman seat in NKP GP9 No. 514 and Bernie was the engineer on the Yard Shuttle. He didn’t talk much, didn’t move fast, but had a little smile of “I love my job” and boy, did he have hands. By that I mean there was no wasted motion, every move on the throttle and brake handles was perfect from decades of doing these motions. It was poetry and I got to see it with my own eyes.

But Bernie didn’t really hit me until I did two telephone interviews with him for my book. In his gravely monotone Bernie would spin these utterly amazing true tales of the rails in the plainest, matter of fact way. Just imagine hearing a first hand account of five D&H E-5 2-8-0 Consolidation locomotives slugging it out of Moosic PA, chugging past Steamtown’s future Scranton home, going on to Carbondale (site of the first run of a steam locomotive in the USA) and there changing out from the most world’s most powerful 2-8-0’s to a sleek, beautiful 4-6-6-4 Class J Challenger! And it was not over yet for there was still the slog over the Ararat grade before racing (literally!) to Oneonta.

I worked with many, many brilliant people in the movie business. But none were a better motivational speaker than Bernie. He had the greatest ability of anyone I ever met to crystallize a life-lesson, hand it over and let it burst within you with the finest epiphany you had ever experienced.

If you were to read the interview transcript, you would think I am nuts for it does not convey what Bernie’s magic was. It was all in that voice sounding like railroad ballast and the magic of hearing it the first time. He did this to all people he met and that is the reason for the reverential tone of all who knew him.

Edd – In our correspondence, you mentioned that, for you, photography is all about the attempt to “capture not just a record, but the meaning and emotion of the scene.” Smoke Over Steamtown does this remarkably well.

Dennis – Anyone who has stood trackside has felt the excitement (and fear) of a train as it roars past. I felt it that first time in Mamaroneck; I feel it every workday at Second Ave and 86th Street as the Q train bursts past me. This emotion motivates every rail photographer, compelling them to go again and again to try to record and thus pass on to others that heightened state of awareness. Being next to objects bigger, (like the Grand Canyon) and more powerful (like a locomotive) the experience releases you from day to day mentality and opens your eyes to being alive. I just try to convey that excitement. I hope I do not sound pretentious but at the root of it all, that is what I desire to do. I am thrilled by this experience; I want others to feel it as well.

Edd – What’s up next? Do you have a new project in mind? What future directions do you see for your work? What new paths would you like to follow?

Dennis – A few years ago Eric Williams said to me that shooting B&W steam locomotives has been done by the finest rail photographers in the world for decades and to do anything different would be extremely difficult. He urged me to immerse myself in my coverage of the New York City subway. This area had not been given its do and I would free to explore. Did I take this wise advice? Of course not! I continued to look for my smoky locomotives. But as Minor White said to David Plowden, I have (mostly) gotten my “damn engines” out of my system and I am now concentrating on my next book, “Transitscapes” which consists my images of (mostly) the New York City subway. I also hope to do a third book that will have a sampling of all my rail images. Lastly, the possibility of photography beyond trains is beginning to beckon me.

Edd – If you could travel back in time to any place in any period of history to photograph railroads, what era would you be most interested in and where would you go?

Dennis – It has been said, and I certainly concur, that history minded people want to explore the time 20 years before their birth. My daughter Kate would have loved to been in the time of the 1960’s jet-set age. I, in turn, would love to go to New York then across the nation to Hollywood in 1939. It was a watershed year in Hollywood as well as for the rails with the New Haven’s Baldwin I-5 Hudson’s streaking between New Haven and Boston and the New York Central’s Dreyfuss Hudsons gliding up their namesake river. Can you imagine taking the Century to Chicago, seeing the huge variety of railroads in Chi Town, then on the Super Chief to LA with a stop over in Colorado for a trip over the Rio Grande Southern? That would be heaven. Even if I had to use film!

Edd – Up until about fifty years ago, railroad photography was almost exclusively black & white. You work in both color and black & white. What makes you decide between black & white and color? Do you know at the time you press the shutter, or do you decide during post-processing?

Dennis –For me, when I am in a special place with lots of action and great light, you will see me running around like a NH I-5 making up time on the “Yankee Clipper.” I am shooting fast, with three cameras, capturing all the moments I can. Frame, focus, expose, shoot, repeat. When I get home I can relax and see the images in 29” iMac razor sharp glory. Then I have a chance, to look, to play, to decide what process the image will be best served by.

Lightroom is for working pros looking to quickly process their images and get them out the door ASAP. It is set up so that you can quickly cull the “best of the best.” That is fine for them, however for me, many times I have gone back to the images I first passed over, gave them more time and attention. As a result some of my favorite images have come out of this process. Lightroom is not as good for this as compared to Aperture.

Yes, when shooting I can say that certain skies, like puffy or angry clouds, do make me think B&W but normally, I am not thinking that far ahead. One side note: B&W imaging is built on contrast and shape and if the contrast/shape is bad, so is the B&W.

Which brings me to contrast. One of my favorite cinematographers, two-time Academy Award winning Conrad Hall had this to say about great images. “Think of the most beautiful pictures you have ever seen, the ones that make you gasp at their beauty. If you stop and look, you began to see the magic comes from the light being ‘light against dark and dark against light.’” I take this and say that our eyes love beautiful contrast; so much so they dance with delight when they see it. Therefore, that is my goal in color and B&W, to make the viewers eyes move like Fred Astaire.

Edd – When you are not photographing railroads, what other subjects catch your eye?

Dennis – Ever since my Dad took me by a New Haven commuter train to New York City, I have been in love with that amalgam of humanity. I find endless angles, endless types of light and endless opportunities to convey the emotion (there is that word again) I feel living in my favorite place on earth.

Edd – Do you have a favorite among your own photographs, one that is particularly meaningful to you? Tell us about it.

Dennis– I imagine all photographers feel protective of their favorite images as their “babies.” At this point I have many, many babies so picking just one would be impossible. However, in the words of Imogen Cunningham, “Which of my photographs is my favorite? The one I’m going to take tomorrow,” let me show a recent “baby,” , one that I call “Green Circle Arch.”

My exploration of the New York City subway system reached a pinnacle with my visits to the closed City Hall Station. Unlike the rest of the brand new 1904 subway system which had tastefully, if minimally, decorated rectangular stations, Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. insisted that the one under his City Hall be a celebration of progress and public improvement in the brand new 20th century. To persuade reluctant New Yorkers, for whom going underground could only mean burial, designers Heins & LaFarge with the help of Rafael Guastavino built a palace underground. Ochre colored, with delicious emerald/black Arts and Crafts tiles, it was illuminated by twelve brass chandeliers for use at night with nine delicately ornate leaded glass skylights in the top of every fourth arch for use during the day. (It is sad to note however, many of the skylights are gone and the ones that remain need rehabilitation) Even though it has been closed since 1945 due to incompatibility with new rolling stock and diminished ridership (less than 200 people a day) the station still makes visitors gasp in humility when stepping out into its stunning multi-arched curved environment.

Tickets for the tours of the City Hall Station that are hosted by the New York Transit Museum are harder to procure than ones for a Taylor Swift concert. These tours, for Museum members only, are few in number throughout the year and pricey for the actual amount of time you are there. (Click here for instructions if you wish to go.) However in spite of this, I have gone three times, each an effort for THE shot. This is one I am happy with for it shows the place with a train but without tourists while showing the best remaining skylight and revels in the sensual curvaceousness of this sepulcherian space. To capture the curves in this confined space, I used a Canon 8-15mm lens on my full frame Canon 6D camera. Its barrel distortion lent itself perfectly to the subject. It also was my very last picture on my third trip before stepping back on the train. Finally, it is one of my favorites because it captures the essence of the transit fan’s ne plus ultra of subway locations.

Edd – What’s in your camera bag these days?

Dennis – I have two Canon 6D’s, one 40D that I bought off Mitch Goldman (some of my favorite images that he took he took with that camera), 70-200mm f/4 IS L and Sigma 100-400mm f/5.0-6.3 DG in Think Tank bags. I use Lightroom on an Apple 29” iMac and OPT/TECH USA shoulder harnesses.

Edd – Is your work mostly digital, or do you still shoot film?

Dennis – As a movie camera assistant, I figure during a 35-year career I ran approximately 3 million feet of Kodak’s finest film through movie cameras. For my personal still work, I went digital in 2006 and have done about 4 rolls of film since. Don’t get me wrong, I love film cameras and I still have all of mine. Today I greatly admire and respect anyone who shoots film since it will long continue to be a valid, if exacting, way to work. But in the end, I really only like it when other people shoot film.

Edd – How has the advent of digital changed the way you work?

Dennis – I cannot think of a way it has not. For me, the first advantage was being able to obtain correct exposure which was something that was unobtainable for me in the reversal film days. Then by having a darkroom for the first time (in a computer) I could finally play with ideas that were impossible when paying a film processing company $12 for a 8×10 print.

Edd – And finally, I am sure you remember “Desert Island Discs”, the radio program where the guests were asked what recordings they would take with them if they were stranded on a desert island. So let’s play “Desert Island Railroad Books.” What three books would you take with you to a desert island, and why?

Dennis – This is easy for I always thought I could only have one book! OK, first one, since I would plan to be there a long time, is a book with every word David P. Morgan ever wrote. However, since that book does not exist, in order to fit the rules, I will go with Morgan’s and Phillip Hastings “The Mohawk That Refused to Abdicate.” Second would be “Starlight on the Rails” by Jeff Brouws and Ed Delvers. This work, with a brilliant forward by Richard Steinheimer, is a collection of the best photographers the world over and is thus unique. It is unique because most photo books about great rail photography are about one artist. This one has a variety of the best night shooters. (A time of day near and dear to my heart.) The third book is a rather obscure title and I relish the opportunity to promote it. It is “The New Haven: A Fond Look Back” by Andrew Pavlucik. The New Haven, being the first railroad I ever knew, is my personal favorite. This book covers the great years of the ‘30’s and ‘40’s before the hideous ‘50’s decline. This is the New Haven of fantastic steam-electric-diesel operations from the shiny iron of the Shoreline to somnolent branchlines. There is plenty of technical and operational stuff to drool over, but the thrust of the book is its view from the men on the engine deck. What ties it all together is Pavlucik’s brilliant writing, writing that is, I kid you not, on par with Morgan.

Edd – Thanks so much for taking the time to be with us, and best of luck to you wherever the tracks may take you.

Dennis – No, thank you for this wonderful opportunity to organize the jumble of thoughts in my head. I can only hope that the reader has come away with an idea or two they might be able to use in their quest of interpreting this fascinating business of railroading.

Photographs and text Copyright 2017 by Dennis Livesey

See more of Dennis' work on his website Livesey Images.