In the fall of 2015, the War on Coal claimed its first two major casualties near and dear to the rail enthusiast’s heart—CSX deemed the mighty Clinchfield to no longer be a through-route, and Norfolk Southern mothballed fifty miles of its ex-Virginian Princeton-Deepwater District. Lines revered as the epitome of railroading in the Appalachians suddenly went quiet. The cacophony of loaded coal trains grinding and groaning upgrade, protesting against the forces of gravity, was replaced with stillness and silence.

It seemed then that the end must be in sight for coal in the Appalachians. All good things must end. But we certainly didn’t expect the end like this, so suddenly, and not before our very eyes.

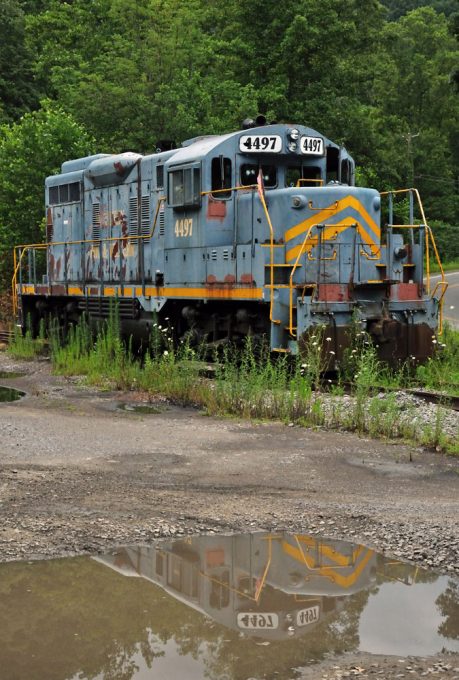

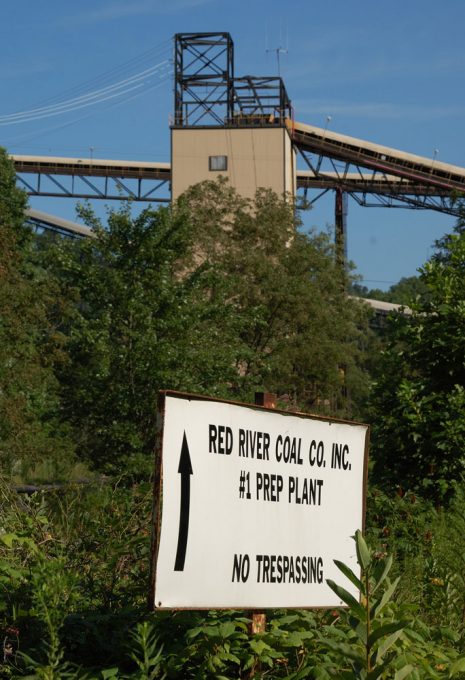

This great misty, mysterious land is increasingly becoming a vast necropolis of closed, decaying and forgotten coal tipples, silos and washers and chutes and loading bins like sad monoliths, monuments to a way of life that is gradually fading away.

Since the first documented coal mining in the United States in 1748, the pasts and futures of coal and railroads have been inextricably intertwined. Ups and downs, booms and busts, good times and bad times, the cyclical swings in the coal business have been felt by both miners and railroaders. Whatever the economy and fate have dealt them, the railroads and the coal industry have faced it together, arm in arm and hand in hand, growing rich and poor together.

My family has coal in its DNA, and coal mining is part of who I am. Both of my grandfathers, and one of my great-grandfathers, were coal miners. They were proud members of the United Mine Workers of America, so much so that one of them had a framed portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt and legendary UMWA boss John L. Lewis, with the inscription “OUR PRESIDENTS” emblazoned across the top. My dad retired from a coal company, the very same company for which I myself worked for a time. Our family’s fortunes and misfortunes could almost always be traced, directly or indirectly, for better or for worse, to the coal industry. Like the railroads, my very being is enmeshed with coal. It should come as no surprise, then, that I would become a railfan photographer, and that my stomping grounds would be the coalfields of Appalachia. Coal—and the dogged pursuit of the coal train—has been such a big part of who I am, and I derive no pleasure from being a first-hand witness to its downfall.

Appalachians are a tenacious lot, and hope springs eternal. Anything is possible. The revival could come tomorrow, or the next day.

What happened here is more complex, more nuanced, than a simple political calculation. To be sure, the policies of the Obama administration were not kind to coal. But to suggest that the malady affecting the Appalachian coal industry is all due to a single political era is disingenuous. Mechanization and automation of the work of mining, beginning as far back as the 1920’s, and the inexorable depletion of reserves, at least ones that are economically feasible to recover, are also to blame. And so is cheap natural gas, and low-cost, low-sulfur, and easily mined coal from the western United States.

The War on Coal is now over. The pendulum has swung back the other way. The political winds have shifted. The scales have been tipped, all in favor of coal. But in Appalachia, the industry doesn’t seem to have gotten the news. The much-anticipated return of thousands of lost coal jobs has yet to happen. My goodness, how I wish that it had. As for the railroads, while some coal has indeed returned to the Clinchfield, the route is but a shadow of its former self, the ex-Virginian mainline remains mothballed, and word is that CSX is considering the sale of many its coalfield lines, including the Clinchfield, the L&N Cumberland Valley Subdivision, and even the ex-L&N Cincinnati-Atlanta mainline.

Appalachians are a tenacious lot, and hope springs eternal. Anything is possible. The revival could come tomorrow, or the next day.

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The handwriting is on the wall, for those brave enough to read it. The end, it seems, is still in sight, even if you turn away and force yourself not to look. And denial has never slowed down the relentless march of nightfall. Rejection of reality only makes the heartache harder.

In the distance, is that the blat of a locomotive horn? The glint of a headlight? The rumble of coal truck, gearing down? The droning roar of the tipple, coal cascading into the gaping maws of hopper cars?

No. An echo, only an echo, or some other sound, mistaken. Wishful thinking. A trick of the light, a fabrication of the heart.

Comes now the darkness, for the torch has gone out.

§

Eric Miller – Photographs and text Copyright 2018

See more of Eric’s work at https://www.flickr.com/photos/ericmiller72

Image Gallery - Click on photo to open in viewer.

A powerful editorial, with photos to match.

Nice writing! I could hear the folk song “The L & N don’t stop here anymore” play in my head as I read your essay.

Great commentary and photos.

I grew up in Floyd County Kentucky which was in the heart of the coalfields. I can remember when growing up there were coal tipples all over the county.There was railroad tracks near my home and loaded coal trains would pass by several times a day.There were trucks on the roads hauling coal to the many coal tipples in the county. My dad was a coal miner, He worked in the mines for 40 years.I have a lot of memories about coal mining in Eastern Kentucky.Its sad but I don`t think the coal mining business will ever come back the way it once was because there is great interest in clean energy today.I think solar,wind ,natural gas and other clean energy has left coal behind.

Thank you for this essay…the coal industry has slowed up here..Crowsnest Pass..Alberta Canada..has always been boom and bust economy…hopefully it will boom once more!!