Earth Day 2018, Pittsburgh and environs

Part Two

Before leaving Polish Hill, George and I did some exploring above the church, looking down the streets and alleys for vantage points. Phelan Way, which runs behind the church and climbs like crazy at its eastern end, up to Herron Avenue, offered a good example of the neighborhood’s flavor.

George found the narrow passage between two buildings attractive, and he had me walk past it a number of times on the next street down, Brereton, so he could capture me in mid-stride in the gap. The large and indolent husky who lived there watched me over the gate with some interest but expended no energy in saying so.

By shortly after noon we had reached Homestead, about seven miles up the Monongahela River from the Point. We had visited here the previous year, and we wanted to try making photos again at a good location that we had found, but first George wanted to pay up-close homage to the last remains of the United States Steel Homestead Works, which employed 15,000 people during World War II and on whose site a mall now stands, with an Ulta Beauty and a Victoria’s Secret and a Barnes & Noble and a Panera and a Starbucks and a 22-screen movie theater—and a dozen hundred-foot-high brick smokestacks on a little swath of grass at the far side of the parking lot, close to the train tracks. I looked in vain for a historical marker or anything at all that would explain these forlorn monuments. None of the steady stream of cars coming in parked anywhere near us, and I cannot imagine that anyone in them even noticed the stacks. Surrounding the stacks, huge floodlights aimed upwards, their spherical housings amply dented and bearing scuff marks that George realized came from the riding mowers used to cut the grass. I made our PB&J sandwiches for lunch and called my parents while George walked up and down the row of smokestacks, making photographs here and there.

Around 1 o’clock we found our way out of the vast parking lot (curiously devoid of directional signage) and back up to the Homestead Grays Bridge, on which we had crossed the river and that now took us into town. We turned right onto 8th Avenue and a quarter of a mile along parked on the side of the street; plenty of traffic passed us, including Port Authority transit buses, but in the next hour and a half I don’t think we saw more than two pedestrians. The stacks still have a strong presence, if one bothers to look.

Two double-track railroads separate downtown Homestead from the former mill site, Norfolk Southern’s former Pennsy Mon Line and CSX’s former Pittsburgh & Lake Erie main. In our brief visit, we saw a few trains on each, including an eastbound stack train on NS, seen here looking down Howard Street—officially closed, with a “Do Not Enter” sign at each end but no barricade.

With the street out of service and no traffic lights to control, the Electro-Matic sensing device (made by the Automatic Signal Division of Eastern Industries Inc. in Norwalk, Connecticut) no longer functions, but its cast-iron and rubber surfaces made an interesting contrast to the brick street which George surveyed:

The fire escapes on the side of the building on the east side of Howard Street cast fascinating shadows on the bricks.

On the other side of that building, an empty lot gave us another vantage to look at the rails and stacks; for this view we stood right on the sidewalk on 8th Avenue. George especially liked the red house, but the narrow field of view and all of the traffic noise behind us did not give a lot of warning of a train’s arrival, so I did not get a good picture of the head end of this westbound; nonetheless, the orange coil cars work well with the brick smokestacks and the red house.

With only a few hours before we needed to get on the road for home—I had to go to work the next morning—we packed up in Homestead and headed to Braddock, a couple of miles up the Monongahela and our last stop on 2017’s trip. Along the way we drove the length of Homestead’s business district on the main drag, 8th Avenue, Pa. Route 837. It has a lot of missing teeth (spaces where buildings used to stand, some of them now parking lots) and empty buildings (the Monongahela Trust building at the corner of Amity Street stands out as a classic needing protection and re-purposing), but overall it looks livelier than one would expect of a town whose main industry evaporated a generation ago and whose population has dropped by almost 85 percent since its peak in the 1920s. From more than 20,000 in 1930, the population had halved as early as 1950, and it dropped steadily and precipitously until 2010. Since then, the fall seems to have arrested, and some of the two and three-story late 19th and early 20th-century buildings on 8th Avenue have new businesses in them, including Honest John’s Bar & Restaurant and Blemah Doo’s African Market. We saw a few ghost signs, including one for Levine Brothers Hardware, and Lloyd Insurance has a well-done and freshly-painted sign on the side of the 1909 brick building at 434 West 8th. That sign overlooks a fenced-in grassy area that holds play equipment for the daycare center inside—not technically an empty lot, because it does get used, and for a good purpose. A few blocks farther on, an older painted sign for Commercial Textiles, on the west side of a building that now houses the office of the local district justice, faces across a parking lot a similar newer sign for Conrad Catering & Delicatessen, still open for business.

A few blocks yet farther, we crossed into the borough of Munhall, and the character of the street changed, with light-industrial uses on the south side of the street (including The Battlegrounds, “Pittsburgh’s Indoor Airsoft Arena”) and a lot of empty space to the north between the road and the river, where a few sprawling pre-fab metal industrial buildings have taken the place of the old mills. In the largest of these, Marcegaglia USA does steel fabrication, but nothing visible outdoors gave any indication of what sort. Across the river, at the Carrie Furnaces, two blast furnaces still stand among a few ancillary buildings and acres and acres of empty fields—the ONLY preserved blast furnaces in the Pittsburgh District. From 1907 until 1978, they made steel for the Homestead Works—as much as 1250 tons per day at their most productive.The river valley narrows here, at least on the south side, with room for only the former Pennsy Mon Line and a parallel branch of the Union Railroad at river level. The former P. & L.E. had crossed the river west of Carrie Furnace, and Route 837, now River Road, climbs up the edge of the bluff, passing the abandoned railroad bridge that once carried the hot steel from Carrie to Homestead. At the top, we reached the intersection with the Rankin Bridge, the multi-span four-lane deck truss that we now took across the river into Braddock.

We had explored Braddock for part of a cloudy day last year, with the tour of the Carnegie Library given by the children’s librarian the highlight. Now on a sunny day, the town looked a little better, but not much. It has lost 90 percent of its population since the zenith (coincident with Homestead’s, in roughly 1920), and now only about 2,100 people call the borough home. Down the whole length of Braddock Avenue, the main street, which runs for a mile between the Rankin Bridge and the Edgar Thomson Works (the very last active blast furnace in Pennsylvania), we could count the occupied buildings on four hands—a screen printer, a small independent auto-parts store, a medical clinic, a state representative’s office in a new but still-largely-empty office building, a new Family Dollar (of course), a couple of small independent markets, a “thrift shop” (junk store, gated and locked on this Sunday, but we had seen it open on a Saturday a year ago), a couple of storefront churches, an optician, two beauty salons (one showing signs of activity, the other with a metal gate pulled across it, conceivably still in business), an employment training center, the Catholic parish hall, the post office, a union hall, and the utterly unexpected Brew Gentlemen Beer Company. In between these, rather than missing teeth, Braddock’s “business district” features yawning voids, whole empty blocks. The mayor for the past thirteen years, John Fetterman, won the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor a month after our visit. I cannot say for certain what he has accomplished in his time as mayor, but he has stuck it out and raised a family there, so he gets my vote for sheer cussedness.

George and I had come back here to look for places where we could photograph the relationship of the town and the steel mill, so we headed for higher ground, first where Frazier Street meets the Pennsy main line . . .

. . . and then on the uphill side of the Pennsy. It turned out that we had crossed into North Braddock, which we later learned has not suffered as much as its immediate neighbor (only a 70 percent decline in population), although on the streets paralleling Braddock Avenue a quarter-mile below one would never have guessed that. Along with many empty lots, we saw any number of abandoned houses—a few burned out, many simply falling in on themselves, vegetation taking them over, and bits of trash almost everywhere. (The amount of windblown trash we saw on this trip in almost every town that we passed through shocked and saddened us.) Some houses did have new siding, new shingles, and mowed grass (and of course, satellite TV dishes) . . .

. . . but the borough plainly did not have a lot of extra money to spend on tearing up and repaving, as here at the top of 13th Street (where, to my amazement, Google’s Street View camera had already gone ahead of us).

So we did find a couple of places to photograph the mill through the houses, but not with the drama that we had hoped for. At the corner of Bell Avenue and Verona Street, in a much more prosperous looking neighborhood, we parked so George could look at a view that included the girder bridge on which the Pennsy’s main line crossed over the street. A middle-aged couple sitting on their porch hailed us; they thought we might have something to do with the history trail through the neighborhood that marks General Braddock’s defeat here by the combined French and Indian forces in 1755. (Interesting and quite ironic that these towns bear the name of an Englishman who suffered mortal wounds in a battle “characterized as one of the most disastrous in British colonial history” [Wikipedia] only a few years before we fought to get the English out of America entirely.) John and Becky (much more John—Becky mostly smoked and sipped something clear from a wine glass) gave us a brief rundown of the local affairs: North Braddock had always had a more residential flavor than Braddock, even though it turns out that most of the steel mill sits in North Braddock, and only a little in Braddock (with the rest in East Pittsburgh), and they seemed generally upbeat about the borough’s prospects. Their dog, Arrow, a mixed-breed rescue, displayed only passing interest in us. George photographed John and the dog, Becky preferring not to have her picture taken.

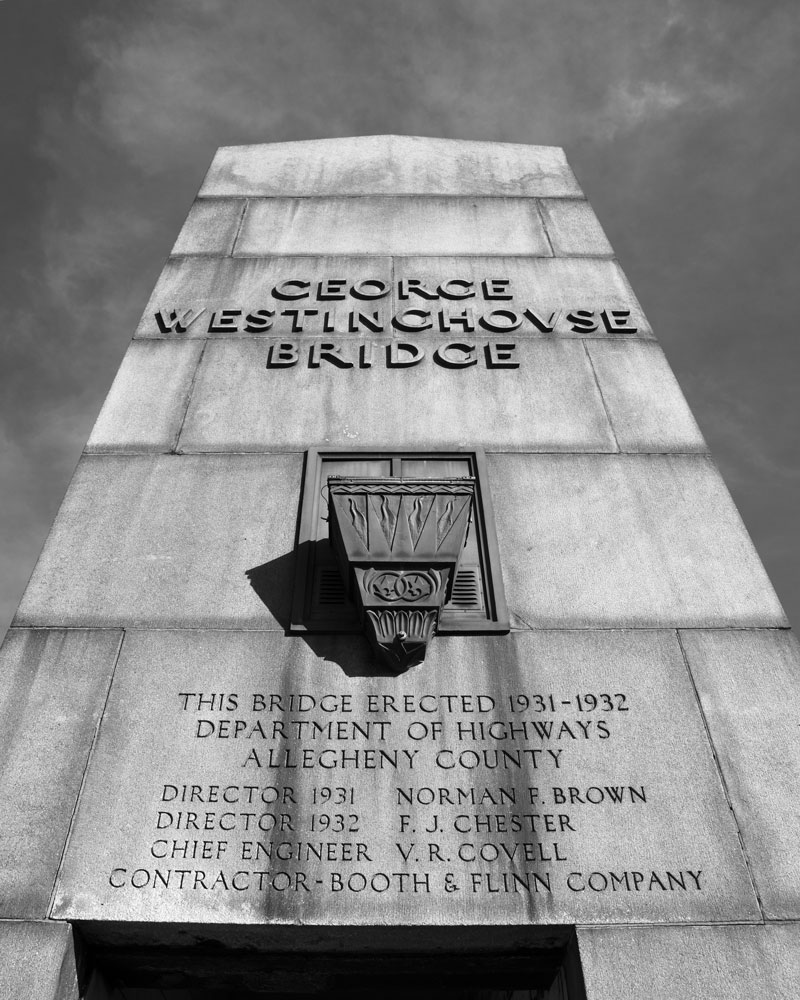

From there we went east, out Bell Avenue, past the dead car-wash in the no-man’s-land between North Braddock and East Pittsburgh, and into the latter borough, passing more tired but lived-in houses. At the T intersection with U.S. 30, the Lincoln Highway, a sign indicated that due to construction we could not turn left to go west, but we could go east, almost immediately onto the George Westinghouse Bridge, a landmark multi-span concrete-arch masterpiece dating from 1931-32. On the way over it we did not stop—we would come back later—because we wanted to find the spot in North Versailles from which an earlier photographer had made a picture that George really liked of the bridge and East Pittsburgh. Between the old-fashioned AAA map that George had marked up and the GPS-directed map on the dashboard, we found our way to the right neighborhood, and we slowly cruised the street on the edge of the ridge, looking for an opening between the trees. The houses varied between well kept and unkempt, and while we did not see a lot of household trash blowing in the grass, we did see plenty of dead cars and scrap tires on gravel driveways.

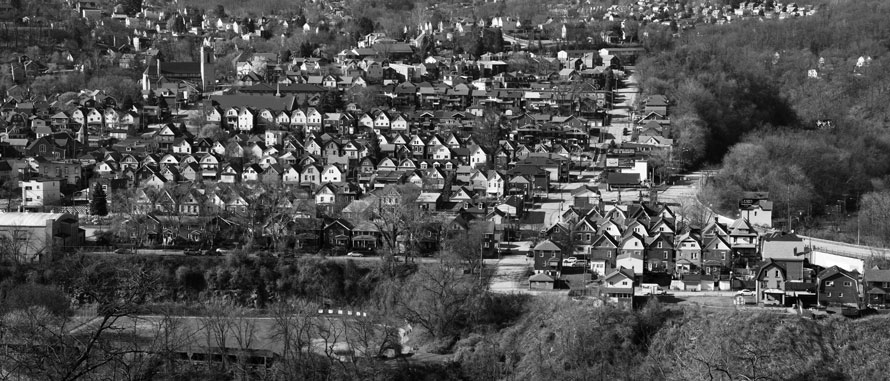

A ways on, we stopped alongside a white-haired woman getting into her car. We showed her the picture that George had copied onto his tablet and asked if she knew where we might go to find that point of view. The longer she talked, the more apparent it became that she did not, for although surely she stood not more than a couple of hundred yards from where the photographer had stood, she directed us all around Robin Hood’s barn to some overlook or other in the next township, or so it seemed. We thanked her, sighed deeply, and drove on. The street started to descend, plainly away from whatever possible prospect we might find, so I turned the car around and right there we caught a glimpse of the gables of East Pittsburgh, half a mile away. The house here looked well-taken-care-of, with a new addition going up in the back, and the backyard looked clear of trees. A handful of vehicles stood in the driveway, so it seemed likely we would find someone at home. On the front porch, a pail full of cigarette butts gave off a foul aroma. The man who answered my knock, perhaps 45, wore a sleeveless t-shirt and a lot of tattoos and not a smile, but he said that we could go into the backyard. “Just be careful, I just had some fill put in, it’s gonna be soft.” He had not used the cleanest fill—down over the edge we could see a minor junkyard poking out from the dirt—but it did give us a view:

Too many trees blocked the bridge. Just to the right you can see the ramp curving up to it at the very edge of the photo. The bland hillside between the houses and the railroads below, plus the modern four-lane slicing through it (out of view below my photo), made for a disappointing location; perhaps we had missed a spot where we could see the bridge better? We drove back up the road, peering between the houses. One gap showed an absence of trees, so we again parked and I knocked on another front door. A teenaged boy answered it, and I explained what we wanted. In the background, I could hear sports announcers on TV. His mother came to the door, wearing a shirt that said something like “You can take the girl out of New York, but you can’t take New York out of the girl.”

“I grew up in New York City,” I told her, after saying yet again that we would like to traipse through the backyard. “Syracuse,” she said to me simply—but she told her son to take us around back. A narrow concrete sidewalk led down into the backyard, and while we could see the bridge, a thicket of trees and brush obscured it: no luck here either. We thanked the boy, and I asked after the game; ice hockey, it turned out, and his team, the Penguins, led Philadelphia by a couple of goals, and he seemed confident. (The Pens would indeed go on to win that game and thus take the series, although they would not make it to the Stanley Cup finals.)

Back at the intersection with 30, the sign said “Road Closed”, but since we had just crossed from the other direction and had seen no actual barriers, I drove us onto the bridge and parked in the right lane; we would surely not get in anyone’s way there. Taking our cameras, we crossed the active lanes (which did not require dodging much traffic: for long stretches no cars crossed the bridge) and we hopped over the low concrete wall and onto the sidewalk. What a view! The steel mill dominated the scene, silhouetted against the far bank of the Monongahela, with a tangle of railroads and tracks in the foreground. I didn’t even know which railroads operated all of them: The former Pennsy main line, the Broad Way, curved against the hillside to the right, and the Union Railroad, once owned by U.S. Steel, crossed over the Pennsy almost under the Westinghouse Bridge, its two-track main heading for a bridge across the Monongahela just west of the mill. But I knew not a thing about the single track on the opposite side of Turtle Creek from the other lines. (I later learned that Norfolk Southern owns it—once the Pennsy’s Port Perry Branch—and that it connects the main line just east of here with the Mon Line on the far side of the river.)

That single track brought us our first train, an intermodal with two Norfolk Southern diesels on the head end, slowly moving under us. The head end of the train had trailers on flat cars—increasingly rare in this age of containers. I photographed it from a couple of vantage points:

As the train slowed to a crawl and I looked away from the viewfinder, I realized that another train had started coming our way, out of the steel mill yard and up the ramp to the Union main. And man, what a sight, as three Union switchers shoved two dozen gondolas loaded with slabs of steel, with a caboose leading, up the steep grade and the locomotives throwing up a vast cloud of exhaust smoke that made a mockery of Earth Day. I hadn’t noticed this train until it had gotten halfway up the ramp, and it caught me quite by surprise. I fumbled with compositions and did not even look closely enough at the time to notice the crewman keeping an eye on the move from the front platform of the caboose, (not that I could have photographed him well from this distance and in this lighting, but I still felt foolish for not even seeing him). In the second photo here the caboose has even started to get obscured by trees.

Just two minutes later, as the Union switchers disappeared under the bridge and out of view, Norfolk Southern sent a train of empty oil cans west on the main, and I could see that their lead units, under their own smoky cloud, would make a fine sight as they hit the reverse curve and aimed towards the sun, but I only had time to make one exposure, the engines still headed away from the sun and their visible flanks in shadow. Behind me I heard someone hail us, and I looked out of the corner of my eye to see a police SUV stopped next to the Subaru. Decision time: Do I wave him off, shout “Just a minute!” and make my picture, or do I do the right thing? Discretion won out, and I climbed over the barrier to talk to the officer, from East Pittsburgh, who had gotten out of his vehicle. “Gentlemen, you can’t park here,” he said, entirely courteously, for which I felt instantly grateful. Okay, I said, I will move the car right away.

“And you really shouldn’t photograph from here.” All of my libertarian – and First Amendment – bells started going off. I do not remember how I asked him why, but evidently politely enough that he gave me an answer which had something of an eye-roll to it.

“Every time people drive by and see someone standing on the bridge, they call us and say ‘He’s going to jump!’ We get a lot of jumpers.”

Okay, I said, thinking fast, how about if we stay out here a little while longer but make sure we keep moving on the sidewalk? “I can’t tell you not to do that,” he said, and he got back in the vehicle and drove off. So I moved the car off the bridge and parked it at the Sunoco mini-mart right at the end of the ramp, walking back in plenty of time to see the next NS westbound go by, an empty hopper train with two units on the front and another two pushing. The pushers made more smoke, but the photo with the lead engines has more of the train in it.

I found the journey overall so satisfying because of the many people whom we met, the memories of whom we will always cherish.

We had set 7:00 p.m. as the witching hour, when we would absolutely, positively, have to get out of town, so I started walking towards the west end of the bridge, to photograph some of it. On another visit we will have to see what we can do to capture the arches from below, but even the pylons above the deck make for very impressive subjects.

I had gone out into the middle of the roadway to photograph the raised-relief sculpture when I saw a group of boys coming up the closed lanes, just out for a walk in the now crystal-clear early evening. Their long shadows struck me like lightning, and I shouted to George, still a ways out on the span and looking at the scenery, “Look at this!”

When the boys saw me, they all shouted “Hey, man, take my picture!” They jumped up on the concrete wall and struck gang poses, complete with hand signs and a handful of cash – but they kept smiling.

I gave each of them one of my business cards, telling them that if they wanted copies of the pictures they should e-mail me. “Sure, thanks, man!” they said and continued on their way, a small happy din wrapped around them as they went. Road traffic had not increased.

Thanks to the ’net, I later learned that sculptor Frank Vittor had studied with Rodin in Paris, came to the U.S. to work for McKim, Mead & White, and settled in Pittsburgh. Judging by the examples of his work here, he certainly lived up to his reputation for having a “preference for the heroic and colossal” (Wikipedia): These reliefs pretty much define “muscular” in every way. George and I wonder: Do the sconces hold lights, and do they work, and if so, what does this look like at night?

Before we left the bridge, I made one more portrait of the two photographers:

The sound of airhorns propelled us back out onto the main span one last time, and fittingly for the end of our trip, the last train we saw had a caboose, as a Union Railroad crew headed south. I’d like to have seen this scene before the four lanes of Braddock Avenue went in. East of here the route becomes the “Tri-Boro Expressway”, Pa. 130, and perhaps the builders had in mind thousands of steel workers pouring into East Pittsburgh each morning and out again each afternoon, but really, can more than a few hundred cars use these ramps every day? How many people really need to get to Braddock quickly anymore, or at all?

At just a few minutes before 7:00 we got back to our car, where we found four more of the neighborhood kids hanging out, right under the “No Loitering” sign. George could not forbear giving them a hard time about their illegal bivouac, and he asked their names; when he could not figure them out (Janiya at the right, then TT – “CC?” he said. “No, TT!” “GG?”) everyone started laughing.

I gave them each my card too, and Janiya emailed me the next day; so did Eric, the boy on the far right in the photo on the bridge, and I sent them their pictures.

It made an entirely satisfying last stop on our photographic odyssey. Okay, third-to-last stop: We did not get on 130 but stuck to the paralleling streets through Turtle Creek and Wilmerding, and I parked briefly alongside the old Westinghouse plant, now a multi-user “industrial mall”, so I could photograph one of the street signs. My friend Ross Gochenaur had sent me a picture he made of one of these after he went there for railroad airbrake instruction not long ago, and I wanted to send him one in return.

A few miles later, in Pitcairn (across the creek from Norfolk Southern’s intermodal yard of the same name), we stopped at a Sheetz to fill up the car with gas and get some supper for ourselves (we had lived by “PB&J ONCE a day” for two weeks). Darkness did not overtake us until we crested the Alleghenies almost two hours later near Horseshoe Curve, and at 11:15 I backed the car into the driveway in Bloomsburg – 262.1 miles behind us for the day, and 2,264 miles since we had left Bloom 13 days, 16 hours, and 15 minutes earlier.

If I had come home with only that second-to-last picture, of the four kids in East Pittsburgh, I would have no complaints, because it shows happiness, and the human connection that even complete strangers can make in no time at all. I found the journey overall so satisfying because of the many people whom we met, the memories of whom we will always cherish.

Let’s go again, George: start making plans!

Oren Helbok – Photographs and text Copyright 2018

Read "Sunday in the Car with George" Part One here.

Great photos and narrative. Especially the enjoy interaction with locals which add a human touch to this.

Very glad you enjoyed it, Jerry, and yes, the human interaction turned a good day of photos into a very special and unforgettable day.

Fantastic photos and text.. they really tell a story. I too like the human touch.

Thank you, Traingeek!

Nice story, there is nothing like meeting strangers and talking about something local to them that is an everyday thing but special to us because we’ve never seen it.

Exactly, John: As I learned from my father, and the way he approached perfect strangers, people like talking about themselves and their lives and what they do and where they live; give them an opportunity and they will welcome someone into their world most generously. I’ve got a list a mile long of experiences that came from this, from a coal mine in Hazleton, Pa. (we drove right down into the pit one Sunday morning in 1985 and got to tour the immense dragline shovel with its crew), to the engine room of a steam-powered Staten Island Ferry (1977 or so), to the clock tower in my hometown’s county courthouse (two months ago). Tell us about your adventures!