Part Three

Peninsula Subdivision

Providence Forge

Margaret Askew was the agent-operator at Providence Forge which was a train order office. During the summers of 1972 and 1973 when I worked at that depot, I never met Margaret nor copied a train order. However, I did handle a couple of small Railway Express Agency shipments.

I heard Margaret on the dispatcher’s line when she OS’ed passing trains. Her voice seemed elderly and all comments about her by other personnel were complimentary. She was among the women who were hired during World War II as telegraphers and had sufficient seniority to stay at Providence Forge as other agencies were closed.

Most C&O depots with manual train order levers had the Union Switch and Signal style with rods connecting to the mast under the floor. Providence Forge and Louisa were exceptions; each had a lever frame with rods that extended through the bay window wall to cranks on the train order mast. Louisa’s were shorter and the operator could move the levers with a left hand while seated. One had to be standing to set the Providence Forge train order levers. I don’t recall ever handing up a clearance card with orders at that station. Switching instructions for car placement was left as a typed message in the telephone box adjacent to the depot.

Providence Forge was a wood, board-and-batten depot building as were most other C&O station structures. Unlike others—and like Lee Hall—it formerly had a bedroom, living room, and small kitchen area upstairs as the agent’s living quarters. I explored the vacant, dusty rooms with the only find being a few 1947 documents completed by Steven F. Thruston while he had worked there as a relief agent. As with most stations, no significant historical documents had survived into the 1970s.

Another difference was that there was an inside toilet over a waste pit. There was no running water downstairs and I don’t know if it had been piped into the upstairs kitchen area. A resident there would need to go downstairs to the commode. I understand that periodically lime would be sprinkled into the pit. This was for the agent’s use only; passengers would use an outhouse adjacent to the depot.

In the early 1970s, the Peninsula Subdivision was double-track. During daylight hours, I observed only one or two passing trains in addition to the local freight that worked from Fulton to Lee Hall. As with other subdivisions, the local freight seemed to operate during second trick. Providence Forge had carloads of lumber arriving, consigned to Mountcastle Lumber Company. It also covered a non-agency station to the west at Roxbury where fish oil and fish meal were loaded. The agent prepared a daily blind siding report and issued the bills of lading for those loads. Those cars ripened under the summer sun.

Providence Forge had mortised locks for entry into the waiting room and agent’s office. Most stations to which I was assigned, I entered through the freight room door secured by a switch lock. The key for Providence Forge was left in a combination lock-box at the Post Office; the combination was provided when a relief agent was assigned.

I hadn’t mentioned it for other train order stations, but when starting the day the agent-operator turned on the train order signal lamps. At the end of the day, they were switched off. A large black box with a toggle switch for each lamp was mounted inside the bay window above the operator’s table. It had two white jewels—one for each direction—with transformers inside to step down the current to lamp voltage.

Williamsburg

I never worked at Williamsburg or the ticket offices at Gordonsville or Main Street Station, Richmond, probably because passenger ticketing was more complicated and required handling of cash. I am unaware of any significant freight agency work for that office although during the early 1970s an Anheiser Busch brewery as well as an adjoining can factory were opened west of the city. These customers were likely handled by the agent at Williamsburg whom I never met.

Lee Hall

This station had a clerk assigned, so the relief agent-operator was responsible for train orders, train passing reports, car orders, and checking the blind sidings, which were only the unused house and team tracks. The substantial freight activity was at the Amoco spur which also led to a Virginia Electric & Power Company generating station at Yorktown. That power station had converted from coal to oil by the 1970s which diminished loading, but occasional tank cars were still handled on the Amoco spur. The other notable traffic was inbound explosives to Naval Weapons. That agency was my only opportunity to view waybills with a lading description of “bombs.”

I worked at Lee Hall only once for a few days. I don’t recall the clerk’s name but came across a note from the dispatcher’s office requesting the clerk to “look out for Scheer.” Indeed, the clerk did guide me on what I needed to do; some other agents left a list of daily activities to be performed. In many instances, it was left for me to figure out. However, if questions arose, another agent on the block line always offered helpful advice.

Hampton, Oyster Point, Morrison, Reservoir, Lightfoot, Norge, Diascund, and Walkers

During my three day, December 1968 hike/hitch-hike along the C&O Peninsula Subdivision, I observed structures at these locations, all of which were no longer in C&O usage. Phoebus depot had been razed and the trestle to Fortress Monroe was removed. I understood that milepost zero still stood inside the Fortress. Hampton was closed and may have been another wood-frame depot that had an agent’s living quarters upstairs. Oyster Point was a small depot while Morrison was about the size of Norge with a large freight room. Reservoir (at the Lee Hall Reservoir) was a waiting canopy without walls, having only upright four-by-four inch supports for the roof. I often wondered about its purpose because there were no other buildings within sight, just the water’s edge. Lightfoot’s depot had been moved away from the track along the north side and converted to a private residence. Norge was boarded-up and derelict at the time, looking much better after relocation and restoration. Diascund had all doors open and a few drifting papers on the floors, blowing in the wind. Finally, the operator’s bay and a waiting room portion of the Walkers depot remained standing after a fire. It’s style was similar to the Louisa, both of which were painted white instead of the usual 1970s grey. Pictures I snapped with a Kodak Instamatic camera during that hike appear below.

Rivanna Sub-Division

Westham, Thorncliff,Maidens, Irwin, Warren, Pemberton, Wingina, Hatton, Walkerford andNorwood

Westham depot had been moved to a recreational area near Parker Field in sight of Interstate 64-95. There was also RF&P business car One at that location. I never stopped to look at either, figuring they would always be there—and of course both are not. My understanding is that the depot was locked without an interior display.

Prior to working for the C&O during 1971-1973, I hiked/hitchhiked for two days during early 1970 between Maidens and Columbia. During a later driving trip, I visited stations after flood waters receded in1972. Maidens had flood waters that reached midway up the walls. A captain’s chair equipped with rollers and an Adams Express cabinet were retrieved. There was a private waiting shelter attractively constructed of stone at Thorncliff. This location doesn’t appear in public timetables as a stop but I expect that the local passenger trains would stop there to pick up or let off the owners of the adjoining estate. Irwin and Warren had open doors and caked mud; there was a wooden train bulletin board in poor condition at Warren which listed the train between Richmond and Lynchburg as well as the mixed freight that made a daily trip to Esmont for a connection with the Nelson & Albemarle Railroad. Pemberton’s train order signal had been dismantled and I retrieved the US&S train order levers and train order spectacles and blades, which I subsequently traded for Railway Post Office artifacts. Wingina was another vacant station filled with dried mud; I met the former station agent named Waddell. He had a pair of C&O Adlake short-globe lanterns without fonts for which I traded a telegraph key, relay and sounder. Near Scottsville was Hatton, where a ferry had formerly crossed the James River. There was a small trackside building which I speculated was a depot since it had a C&O-style depot sign on its side. Walkerford was West of Gladstone; while hiking along the right-of-way, I observed that the depot had been moved away from the tracks and converted to a private residence. The owners invited me inside for a chat; I doubt they received many other visitors. Like Walkerford, Norwood was on the James River Sub-Division, but the vacant station had been cleaned by a local resident who donated some motor car track line-up forms. A friend later spirited away one of the Norwood station signs. Photos of several of these locations appear below.

Sabot

This depot was the quietest place I worked despite being about fifteen miles west of Richmond on the Rivanna Sub-Division. The building was about 100 yards at the bottom of an unmarked driveway off of Virginia Route Six. The station was damaged from the Hurricane Camille flood that ruined Maidens, Irwin, and Warren stations, but had been cosmetically repaired with drywall and a drop-ceiling. Two agents were there during the 1972 and 1973 summers that I worked there. One was a Mobile Agent that covered the closed agencies between Sabot and Bremo, as well as the Virginia Air Line. The Mobile Agent’s last name was Moore and I forget his first name, as well as who the regular agent-operator was for Sabot. I covered that position, which was responsible for a spur near Dover Farms Road which received occasion loads of agricultural lime. The main responsibility was for outbound crushed stone loads from the Luck Quarry at Boscobel. About thirty cars were loaded daily during weekdays, the largest number of waybills/bills of lading and demurrage records of any location I worked. I’d receive car numbers for loads around 2 p.m. ahead of a local freight that picked up cars in the evening and spotted empties, so I’d type most of the recurring information on the bills of lading such as origin, destination, and commodity. That left adding car initials and numbers as the only remaining entries.

I used Sabot as overnight lodging during weeks that I was assigned to R Cabin during day shifts, covering Scotty’s vacations. Evening or night tricks were rarely five consecutive days so when covering those assignments, I drove from and to Charlottesville, submitting mileage and per diem expenses for each trip. When staying at Sabot, the two agents departed by 5 p.m. before I arrived. I left the following morning by 7 a.m. prior to their start time at 8 a.m. Access to the station was via a switch lock on the freight room door. I carried a cot in my car along with a box fan. Usually it was warm inside the depot with the air conditioner off and the fan kept me cool until around midnight. Wood-frame C&O stations had no insulation so as June through August temperatures dropped to the 50s along the James River, a sheet or blanket was required instead of a fan. There was no running water at Sabot; I filled a drinking water container from a nearby spring. The outhouse was rustic as they were at other locations, usually home to hornets. Fortunately, they did little buzzing overnight during darkness and cooler temperatures. When using the outhouse, the door was left open so that if they did stir, they had a clear flight path to outside rather than circling my head seeking an exit.

The mobile agent had a station wagon which was driven into the freight room and secured at night behind the sliding doors. I thought about sleeping inside the station wagon once—and only one time. Mr. Moore was a chain smoker that kept the Phillip Morris factory running at full capacity. I could only stand about fifteen minutes inside the car before resorting to a cot in the office area. The office area included the space of two small waiting rooms; interior walls dividing those rooms and the agent’s office were removed so that there was an L-shaped office area around the freight room where the car was stored.

Mr. Moore described the Mobile Agent’s daily itinerary. Starting from Sabot in the morning, he drove to each of the closed stations such as Maidens and Pemberton where pulp wood was loaded, usually consigned to either West Point or Covington, Virginia. Pulp Wood was also loaded at Troy on the Virginia Air Line although there were occasional highway department carloads spotted at Zion for unloading. At locations where there were outbound loads for the day, he used a portable typewriter to prepare bills of lading. Mr. Moore said that it was challenging to sit sideways on the front bench seat and type. A restaurant adjacent to the Fork Union Military Academy was the preferred lunch stop or coffee break location en route. After completing his stops along US Highway 15, he returned at the end of his shift to Sabot via Virginia Route 6. Back at Sabot depot, he updated demurrage records, ordered cars, prepared blind siding reports, and submitted freight invoice copies to the Zone Accounting Bueau at Richmond.

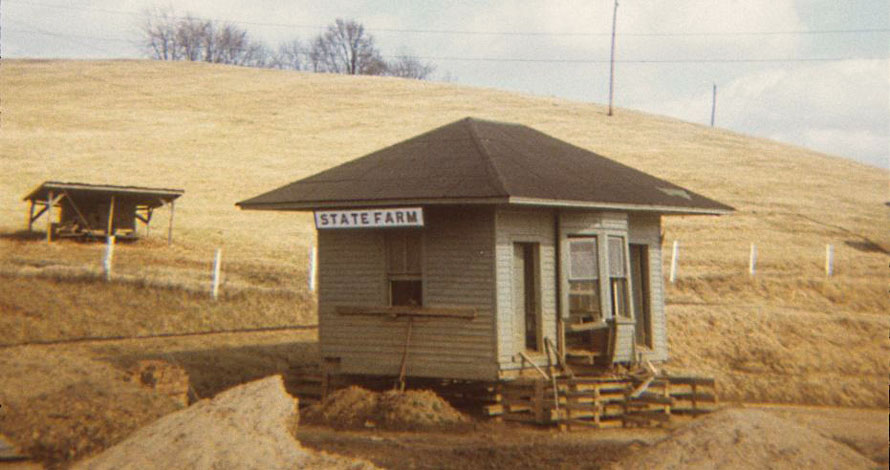

I never had any scary occurrences at Sabot. Mr. Moore told me that one time earlier in his career when he was staying at Maidens depot that someone was rattling the doorknobs late at night. It turned out that an inmate at the “State Farm” nearby had escaped and had probably been seeking a place to hide.

There may have been a small community at Sabot. By 1972, the only other structure in sight was a former general store building inside the fenced area for a farm. It was being used for hay storage. Although Sabot was perhaps fifteen miles from downtown Richmond, it seemed like the most remote place anywhere along the C&O. It was absolutely dark with only starlight or moonlight at night. Crickets orchestrated nightly concerts with the dull sound of the rushing James River as background. It was easy to imagine earlier years of approaching steam engines. Sabot depot was at the eastern edge of a long curve adjoining the riverbank. Looking out the operator’s bay window at night, the headlight haze was visible for several miles before the beam burst around the curve, sweeping towards the station. Black shadows of hopper cars followed, caboose markers pierced the night as it passed, then all was still again with the faint rumble of diesel engines fading in the distance.

During the Hurricane Agnes recovery in August 1973—my final summer working—theRivanna sub-division signals were dark. For about two weeks after the roadway was reopened to traffic, the line between Sabot and Gladstone was divided into three manual blocks: Sabot-Shores, Shores-Scottsville and Scottsville-Gladstone. I’ll describe my work at Shores and Scottsville later, but will mention Sabot now. The office had been flooded up to the ceiling so that all paper records and phone equipment was destroyed or inoperable. There was a shortage of extra operators, so that anyone available worked twelve hour tricks at those three manual block offices. James L. Pickett, the Chief Train Dispatcher, filled one of the overnight vacancies at Sabot, using a portable telephone connected to a twisted-pair cable laid along the right of way for communications. Lacking train order forms and clearance cards, he wrote the manual block order and clearance card on plain paper for a westbound empty hoppers extra train. It was an interesting anomaly for him to copy a dispatcher’s order with the initials J.L.P.—his own as Chief TrainDispatcher—then sign the order “Pickett, Opr.” I was at Scottsville copying the hold-order for eastbound trains. When I handed up the clearance card and order at Scottsville for that train,I included a self-addressed stamped envelope and note to each conductor and engineer. My request was that if they didn’t want to save the order copied by Jim Pickett, to please mail it to me after the trip. I received the order from one of them and still have it somewhere.

Bremo

Prior to working summers on the C&O, I had visited Bremo. The Hurricane Agnes flood had damaged the depot but it was returned to service briefly before being razed and replaced by a portable building. That was swept away between 1971 and 1972, then replaced with a former troop sleeper converted to a camp car. A track panel was set on the depot site and the camp car on its trucks was placed on the rails. The clerk who worked there whose name I don’t recall quipped that he was the only clerk who had his own private car. He drove a boat-tail Cutlass and had an easy-going demeanor.

There was a good reason for a clerk at the Bremo agency. Virginia Electric and Power’s coal-fired generating station was a spur off the east end of the doubletrack between Bremo and Shores. Mainline coal trains set off loads into Strathmore yard, which westbound empties trains pick up hoppers. A local freight from Fulton spotted about twenty-five to thirty-five loads at the power station daily, as well as pulled a similar number of empties. The local freight crew picked up loads according to the car numbers specified by a switch list that generally moved the oldest-arriving cars first, then shoved the empties into Strathmore yard before continuing to Dillwyn to switch the aplite mine. This same local worked Luck Stone en route during its return to Fulton during late afternoon or early evening. Other stations between Westham and Bremo were spotted with empties as required during the morning westbound trip, then loads were picked up during the eastbound return.

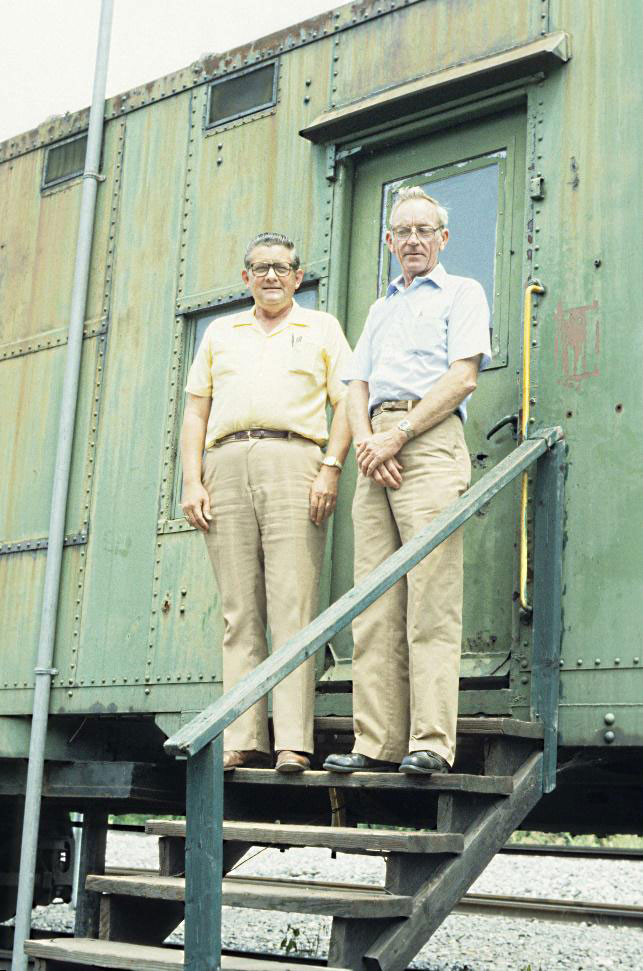

The clerk who I worked with—shown in the photograph above—took care of records-keeping such as the average agreement demurrage, filing waybills, and sending the freight bills to the Zone Accounting Bureau. The agent prepared and executed bills of lading, handled car orders, and received the information for the next day’s switching of the power plant coal yard. The agent also drove over to Strathmore to prepare blind siding reports for each track. If the first and last car initial and number on a track matched the prior day’s listing, then no further check was required. Otherwise, the agent walked the track and recorded the car identification from west to east on the blind siding report card.

There was no train order signal at the replacement station buildings. The Rivanna Sub-Division was entirely Centralized Traffic Control territory, so Bremo had not been a train order office since nearby Strathmore—while it was still open—was. Train passings were reported to the dispatcher but that was an anachronism since the track display on the dispatchers CTC machine alerted him to train locations. I believe the Rivannna CTC machine had graph paper with inking needles that recorded train movements.

The other responsibility at Bremo, as well as at G Cabin, Sabot, and Columbia, was requesting train line-ups from the dispatcher for maintenance of way forces. One foreman was named Mr. Wilkerson. I assume his gang handled spot maintenance needs in between rail and tie programs by travel.

Shores

Shores was at the west end of double track. It became a block station during the couple of weeks without trackside signals and CTC controlled turnouts. I did one and perhaps two nights there by driving to a road that dead-ended at the C&O right-of-way. I pulled over along the gravel, connected a portable lineman’s phone to the twisted pair cable laying along the track, then sat in the car for twelve hours. Most of the time I kept the windows rolled up even though my 1965 Dodge Coronet wasn’t air conditioned. The reason to endure stuffiness was that it proved to be a better alternative than swarms of mosquitoes that hatched from flooded meadowlands. That was a dusk to dawn assignment with only one or two trains during a twelve hour period. My responsibilities were to insure that the turnout was spiked in addition to copying manual block clearance cards and reporting train passings as they cleared a block.

Columbia

It’s a pity that I never met the agent at Columbia, nor do I remember his name. During 1972 and 1973, I worked at the depot in that village for a couple of weeks each summer. I enjoyed the location for a few reasons. First, it had steady—but manageable—agency work. Unlike preparing fifty or so bills of lading at Sabot for the Luck Quarry crushed stone shipments, there were an average of five pulpwood carloads daily. Second, there was AMO’S CAFÉ a block away which had little business, but their country ham sandwiches are still tasty in memory and a welcome break from canned stew which was my usual fare during out-of-town meals. If canned stew sounds rustic, it wasn’t much better than the Swanson “TV” dinners that I baked in the over at my Charlottesville apartment. Finally, the community was interesting to browse, measuring only three blocks along Virginia Route 6. It had been devastated by the Camille flooding during 1969. Hurricane Agnes finished the job four years later; the second of a one-two punch.

The highway bridge across the James River to Cartersville was damaged by Camille flooding. By the time I worked there during in 1972, it had been rebuilt. Water had reached halfway up the walls in the depot during 1969, so there was nothing of significant age in the station. Waiting rooms were empty, as was the freight room. The operator’s desk in the bay window had screw holes which depicted the placement of telegraph instruments before they were removed during the 1950s. I was told that all of the removed instruments had been stored in the freight room at Covington depot but of course were long gone by the 1970s.

Pulpwood loading was across the road from the depot along a team track. The consignor would stop by about 3 p.m. with the car initials and numbers and the consignee information. Loaded wood rack cars either went to West Point or to Covington for paper production from the pine pulpwood. I had heard that the C&O wanted to discontinue handling pulp wood loads because of low revenue as well as that sometimes a log would loosen and protrude beyond the edge of the car body, creating a potential hazards for trackside structures or passing trains. Nonetheless, during the early 1970s, pulpwood loads were the principal commodity shipped from stations along the Rivanna Sub-Division.

While sleeping at Columbia overnights between Monday and Friday, I’d usually awaken for an approaching train, watching the headlight flash past followed by dark shadows of hopper cars. The local freight from Gladstone also visited Columbia during the midnight hours, stopping to pick up the previous day’s loads and spotting empty wood-rack cars for the coming morning.

During one of the days that I was working at Columbia, P. D. Hulbert stopped by for an audit. He supervised agencies on the Richmond Division, and I surmised that he selected a day when the assigned agent-operator was on leave. I’m uncertain what he reviewed or why, but concluded it was to support a decision whether to close the agency.

After 1973, Columbia was indeed closed following Hurricane Agnes flooding moved it off its foundation. The depot building was relocated to a lot about a quarter-mile west along Virginia Route 6. It was planned to be a community center but during a 2016 visit the building is unused and vacant, but intact.

Scottsville

Scottsville depot was a neat, small brick depot in which flood waters during 1972 reached the ceiling. It was the only masonry station building in which I worked on the Richmond Division other than Beaverdam. C&O had a propensity for wooden structures and if Scottsville had also been of board-and-batten construction, it likely would have floated down the James River.

The depot had been partially cleared of caked mud but some remained on furnishings and walls. Nothing of use remained in the depot. I don’t know who the regular agent-operator was at Scottsville and never met that person. There were no usual agency activities during the two weeks I was there following the Hurricane Agnes flooding. I was solely an operator at a manual block station in dark territory. There was a single twisted-pair cable along the right-of-way between Gladstone and Richmond, linking block stations at Sabot, Shores, and Scottsville. These blocks were very long and trains were fleeted, so that all during a twelve hour period they were operated in the same direction. I recall only two trains at the most during a twelve hour shift and I was always assigned to the 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. trick. There was little to do other than prepare a clearance card for the block after another office reported a train had cleared the station, watch for an approaching train to hand up a clearance card and any orders, and to report train passings. Now that decades have passed, I’ll confess that I pulled out the cot from the car and napped during the lulls. There was little else to do by the light of a battery-operated hand lantern; electricity had not been restored to the town. When a train approached, I positioned my car so the headlights shined upon me for the engineer and conductor to see where I was standing with train order forks in hand. I used this same technique during the nights at Shores.

Gladstone

During the daylight shift, there were only a couple of trains departing. After eastward trains were called, I called the dispatcher to prepare a clearance card. The arrival and departure information was passed to me for me to relay to the dispatcher since I couldn’t see train activities through a window. There was no car billing activity or blind siding car checks since Gladstone was a yard. Frankly, I don’t recall what filled my time for eight hours. The position was obsolete and didn’t last long after my final day during 1973.

The yardmaster was upstairs in the depot. I don’t know what the actual yard activity was other than making up local freight trains. Gladstone was a holding point for tidewater coal, so some trains called were bound for the Newport News Piers. However, most trains from Clifton Forge ran through Gladstone and stayed on the main line as a run-through train, as did trainloads of empty hoppers from Richmond heading back to the mines. I don’t recall manifest trains passing through Gladstone and believe they mostly operated over the Mountain and Piedmont sub-divisions.

The only remarkable incident I recall local employees mention was some prior summer that the thermometer in the roundhouse was 111 degrees. There was also a Railroad YMCA with a 24-hours lunch counter in a relatively new cinderblock building. Train and engine crews not living in Gladstone laid over there, which was roughly across the main line from the depot.

The Richmond Division operator’s desk was a free-standing wooden desk with telephone, plug box, bells, and ringer mounted on the desktop. The only additional item I never observed elsewhere was a strap key that was no longer connected with wires. I suppose it had been connected to a wall clock which allowed the operator to listen to the time signal and reset the clock precisely at noon. By 1972, only a Telechron clock was on the office wall, not marked “Standard Clock,” and no one that I recall set their watches to its time. That tradition was obsolete in the era of Centralized Traffic Control when all trains were extras and trains moved according to signal indications, not by timetables and train orders.

Virginia Air Line Sub-Division

During 1970 while attending the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, I did not have an automobile. While others were attending fraternity, entertainment, or athletic activities, I explored the Southern and Chesapeake & Ohio Railways by hiking along the right-of-ways. My first adventure during the Winter break was a ride with a student heading to Newport News, then hiking to Phoebus one day, between Newport News and Norge the next day, and from Norge to Providence Forge on the third day with hitch-hiking back to Richmond and a train ride back to Alexandria.

Another hike was from the east end of Charlottesville Yard to Orange, returning by Greyhound bus. Along the way, I paused at Lindsay looking at the sidings and an approach signal. Being a novice, I was unaware that there were no longer trains operating regularly over the full length of the Virginia Air Line. I learned later that there was an occasional local freight that traveled from Lindsay to Troy to spot empty wood rack cars and pull loads.

Spurred by an interest in the thirty-eight miles between Lindsay and Strathmore and figuring that at about three miles per hour I could cover most of the route within two days, I began hiking from Charlottesville to Lindsay shortly after midnight so that I would reach Lindsay before dawn. The only nervousness along the way was crossing the Rivanna River trestle at the Woolen Mills. Rushing water underneath made it difficult hearing approaching trains, but trains between Charlottesville and Gordonsville were scarce between midnight and 6 a.m.

Reaching Lindsay, I turned south along the VAL and learned why the signal heading down the branch was always showing an approach indication. There were unused, rust-covered set-out tracks between Lindsay and Whitlock. At Whitlock, there was a home signal set at stop.

From Whitlock down to Zion, there was mostly tangent single track. A road crossing bell near Zion malfunctioned and was ringing incessantly. All of the automatic block signals en route were approach-lit and all were dark. Coming around a curve, I entered the village of Troy where a couple of pulpwood cars were being loaded. As the end of daylight approached, I reached Palmyra where I spent the night.

I learned that as a result of Hurricane Camille a year earlier which devastated Nelson County, there were two areas of erosion at which ballast had been dumped to stabilize the roadbed. One was a curve about a half-mile north of Palmyra. The other, more severe, stabilization was a mile or two north of Strathmore.

The station at Palmyra was still in existence, although its days were numbered. One of the Williams brothers was agent for a half-day at Palmyra; the other half was at Fork Union for which the depot was two miles away at Carysbrook. Neither were train order offices. I unlocked the freight room door with a Southern switch key which happened to fit into the C&O Adlake lock keyway. About as much as I remember about that office was that it had an Automatic Electric desk phone for the block line and dispatcher line. Palmyra was the agency that covered the wood loading at Troy, which by 1972 was shifted to a mobile agent operating out of Sabot. There was no other freight traffic that I observed at other locations, including Palmyra.

The next morning came early as I continued walking into the most isolated but scenic section of the VAL. The railroad followed the curve of the Rivanna River from the overpass above US Highway 15 at Palmyra—now removed—to a road crossing a mile north of Dixie, Virginia. Rockaway was midway; all that marked the location were the concrete footings for a water tank. After crossing the highway, the Carys Creek trestle was just beyond, which was the highest bridge on the VAL. I decided not to cross that bridge and instead hitch-hiked to Fork Union via Virginia Route 6. At the east side of town, I walked down West River Road to the VAL at Cohasset.

The depot remains without a track as of two years ago and is derelict. The remaining six miles to Strathmore were covered on foot; the more significant roadway embankment repairs from 1969 flooding were visible about a mile from Strathmore.

The depot at Strathmore was still standing but mud-caked and unused. Flooded out papers and furnishings were strewn within the open doors and windows. An adjacent crew dormitory was on higher ground with less flood evidence but likewise abandoned. There was a mile-long gravel-and-dirt driveway back to US Highway 15 at Bremo, which is where I concluded the day by hitch-hiking back to Charlottesville.

Near the end of the 1973 summer, Assistant Trainmaster Frank Schumaker alerted me that the final train would cross the Virginia Air Line. He offered a cab ride with him and the crew to observe the end of service prior to abandonment. We departed from Charlottesville yard, ran around a cut of cars at Lindsay, the proceeded down the VAL. Frank sat outside on the steps to the cab on one side, while I sat on the steps along the other side. The speed limit was about 25 miles per hour and so during the trip down to Strathmore and back to Charlottesville via Lindsay, everything I had seen two years earlier at a slow pace seemed to streak by. I also saw the portion of the VAL I skipped over the Carys Creek trestle and another bridge a little further south before passing the Fork Union depot at Cohasset. It was the end of the day by the time we were back at Charlottesville aboard light engines, with memories to last a lifetime of the Virginia Air Line, where there are now no rails.

Frank Scheer – Photographs and text Copyright 2018

This is the conclusion of the three-part series on the C&O Richmond Division. Part One is here, and Part Two is here.

What a marvelous recollection ! The photos are priceless…..some of them are of stations (Bremo, etc) that I’ve never seen before. Thank you for this great trip down memory rail….er….lane.

Thank you for sharing all of this, glad you took all those pictures I’m sure all of us agree we never took enough pictures thinking “it” would always be there

Enjoy reading anything I can find on the peninsula subdivision. Just one slight correction. It was the Ewell (or Ewell Hall) station that was moved and turned into a private residence. Ewell was between Lightfoot and Williamsburg. Lightfoot station was never moved and was torn down. I was there when they tore it down. My grandfather was The station agent there at one time in his house was next to the station.

My uncle, James B Tindall Jr, was stationmaster in the 1950’s of the Hatton depot. He also ran the general store and post office located a short distance from the depot, and I believe his grandfather or father had been instrumental in helping to run the Hatton ferry before turning it over to the state in 1940. He and my aunt lived in the large Victorian style house located on the hill above the store/depot. Sometime in the late 1960’s he purchased the depot from the C & O and did convert it into a small summer cottage. Camille came through and flooded the area, but it was Agnes in 1972 that picked the depot up and floated it downstream if my memory serves me correctly. It was a real pleasure to see this picture, as I have not seen it in many, many years. Would it be possible to obtain a copy of the image?