Cape Horn near Celilo, Columbia River, 1867

Oregon Historical Society

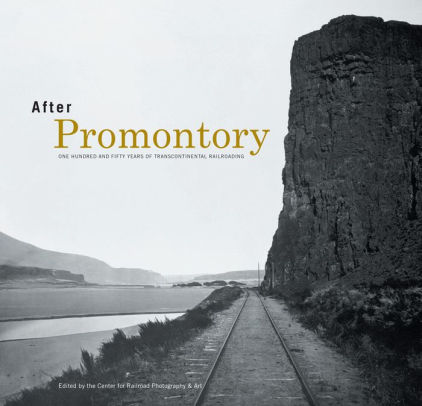

After Promontory: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Transcontinental Railroading was put together by the Center for Railroad Photography & Art and published by Indiana University Press. With the sesquicentennial of the Golden Spike looming, the creators of this book chose this time to look back not only at the Pacific Railroad, but also the subsequent transcontinental railroads, and the myriad ramifications of the industry, writ large, since Stanford wielded the maul on May 10th 1869 at Promontory Summit.

After Promontory begins with a forward by Robert D. Krebs, former Chairman, President, and CEO for BNSF Railway, which lays out the structure of the book, followed by an introduction by H. Roger Grant, historian at Clemson University. Grant provides us with a concise history leading up to the first transcontinental road, later known as the Overland Route, including Asa Whitney’s dream as well as the concrete, and prescient, results of the Pacific Railroad Surveys of 1853. He pivots nicely to how photography functioned as a marketing tool for all of the eventual railroads that made it deep into the West. Established railroad historians Keith L. Bryant, Don L. Hofsommer, and Maury Klein provide the book’s major essays—the reader may recognize these names from their own dog-eared histories of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, the Southern Pacific Railroad, and the Union Pacific Railroad respectively. Drake Hokanson, a photographer/writer who has covered the original route of the first transcontinental railroad extensively, penned the final essay, with a focus on the symbiotic relationship of railroads and photography in the 19th century, and he supplied many images as well. Peter A. Hansen, steward of the journal Railroad History, performed editing duties. (It should be noted that I contributed nine photographs to this volume—five large plates and four small illustrative vignettes.)

The knowledge and insight of these scholars serves as sturdy mortar that holds together a wealth of images, which makes up the bulk of the volume. Slightly fewer than half of the images are by 19th century practitioners, including many works by household names from the history of photography itself. It is natural, of course, that many images appear from Alfred A. Hart and A. J. Russell, who did yeoman’s work documenting the construction of the Pacific Railroad, but also from F. Jay Haynes, someone with whom I was not familiar. The remainder of the catalog is split between modern image makers from the third quarter of the 20th century, roughly speaking, and those still working in the field today. As with the stable of essayists, the photographers involved are likely familiar to those readers who study western railroading, and the book has been fortified with the work of several photographers who truly represent the canon.

The main content of the book is structured via three geographical tiers cutting across the western two-thirds of the United States—central, north, and south. The central section covers the Overland Route, which sets the table. The southern section covers the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe and Southern Pacific’s Sunset Route along with some ancillary roads. The northern section is a study of the Northern Pacific and the Great Northern along with the latecomer Milwaukee Road. Each of these tiers is covered by a lengthy historical essay by the aforementioned authors followed by two photographic galleries—the first dedicated to historical views and the second to modern and contemporary imagery. It should be said that the essay pages themselves are not without some wonderful images.

Jeff Brouws and Wendy Burton handled the layout and design work, arranging all of this content in an attractive and elegant fashion. And while their names do not appear prominently, this combined project was the brainchild of Scott Lothes, Executive Director of the Center for Railroad Photography and Art, and Alexander Benjamin Craghead, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley. Mr. Craghead curated the images for the exhibit and assisted in a similar way with the book.

The Overland Route

It is natural that the combined Pacific Railroad, made up of the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific, would function as linchpin in any discussion of transcontinental railroading, and so that is where After Promontory begins. Maury Klein, Professor Emeritus from the University of Rhode Island, well known for his three-volume history of the Union Pacific Railroad, takes on the assignment.

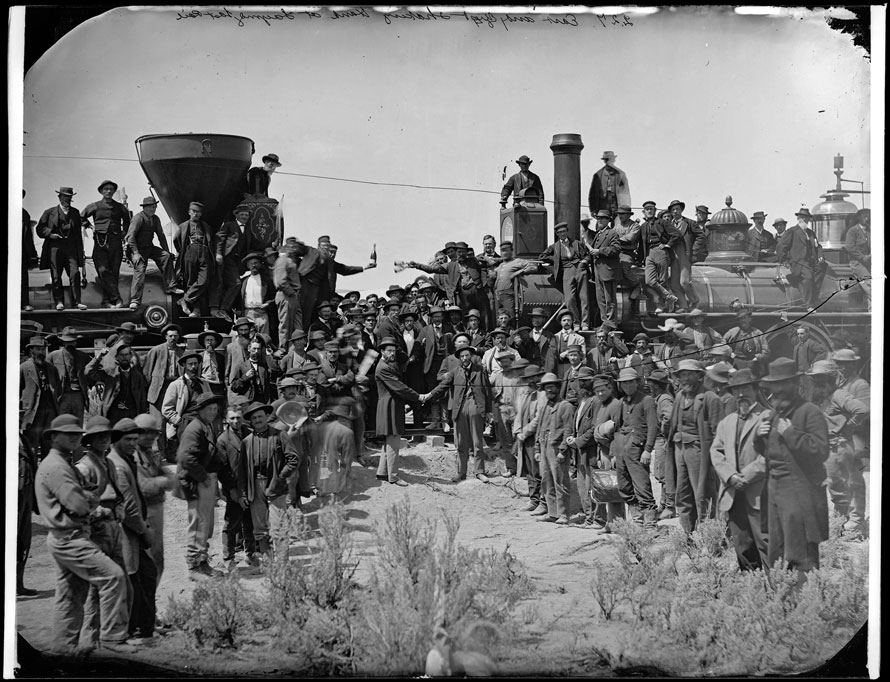

East and West Shaking Hands at Laying Last Rail, 1969

Oakland Museum of California

Klein begins with the symbolic importance of what occurred at Promontory Summit with the joining of the rails. “If there is one event that reflected the changing world of the nineteenth century for Americans, it was the driving of the golden spike, signifying completion of the first transcontinental railroad.” (p. 16) He writes of how truly transformational this achievement was—in particular the dramatically shortened travel time to California—but is quick to address controversial aspects of the line. To assist here, Klein brings in the work of historian Richard White, whose book, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America, was critical of the railroad construction boom that is the very subject of After Promontory. White argued that these railroads were built too early, too often, and had a habit of going bankrupt repeatedly. To balance these criticisms, Klein quotes Alexis de Tocqueville with his characterizations of American energy and impetuousness. Klein acknowledges lines were built ahead of demand, but that they were expected to create commerce out of emptiness and, after the extreme austerity of the Civil War, Americans were interested in a little self-interest. And so “circumstances favored the grand project of the age.” (p. 28)

After a prelude to the project, Klein provides a summation of how the building of the first transcontinental railroad progressed, both physically and as a moneymaking enterprise for the principles on both the Union Pacific and Central Pacific. Along the way Klein does acknowledge how this incursion negatively impacted bison, a primary food source for the Plains Indians, which would push them to the brink. He then delves into the scandalous aftermath of the building of the Pacific Railroad as well as how the two railroads fared generally into the next century. In the end, Klein feels that, “The first transcontinental set the pattern others would follow, leaving in its wake not only a ribbon of steel but a new and expanding economy, society, and culture all along its route.” (p. 42)

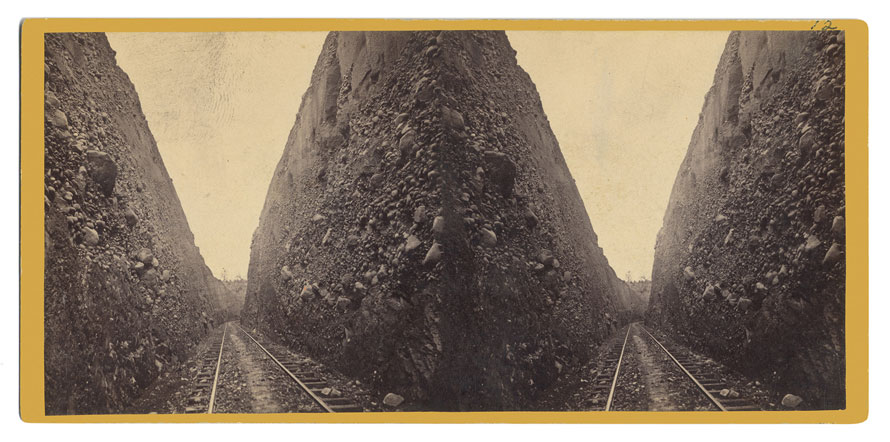

Historical Views

Having been obsessed with the first transcontinental railroad for the last nine years, I always take pleasure in viewing any and all of the historical images associated with the construction of the Pacific Railroad. One truly refreshing aspect of this volume is that the 19th century images supplied here, even when captured by well-known figures such as Russell and Hart, are not the same views one may have seen repeatedly while perusing the texts covering the building of the first transcontinental railroad. The images are served up in a thoughtful manner as well, with minimal or no cropping, allowing the details to show, such as flaking collodion emulsion on the glass plates. Hart’s stereoscopic views of the Central Pacific are often presented as a complete entity, scanned entirely with their yellow borders and accompanying text, along with a shadow that describes its thickness as a physical entity. This tends to be a distinctly 19th century characteristic of several photographic processes—these pieces are both image and object.

Bloomer Cut, 63 feet high, looking West, 1869

Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Being a stickler for how images are optimized, primarily in the management of contrast and sharpness, I am happy with how nearly all of the images in After Promontory appear. In this sesquicentennial year, many of these historical documents have shown up in many publications, and the results have not always been as pleasing. While the historical plates and prints are technically monochromatic, they do have a hue of their own, and the full color reproduction employed in this book delivers this inherent warmth.

In the first “Early Views” gallery, most of the images are by revered giants from the history of photography: Timothy O’Sullivan, William Henry Jackson, Alexander Gardner, Eadweard Muybridge, as well as Carleton Watkins. This provides real substance for those of us who consume the history of photography as a complement to that of the railroad. Another name from this history is John K. Hillers, who provides us some fine historical views of the Canyon Diablo Bridge in the second historical gallery, while F. Jay Haynes dominates the third.

Southern Region

Keith L. Bryant sets the stage for this entire era of empire building via the well-known John Gast painting of 1872, American Progress. Expanding aspects of civilization—settlers, farmers, and railroads—move right to left across the frame, while Native Americans, a bear, and the all-important herd of bison flee for their lives. The center of the painting provides us with the personification of civilization itself: an ethereal, larger-than-life woman, carrying the book of knowledge and spooling out telegraph line as she moves forward. He states, “The popular work vividly depicted the concepts of Manifest Destiny and American exceptionalism that were central to the national character.” (p. 138)

It is impossible to visualize the contemporary Southwest without considering the past and present contributions of the railroads.

By the time of Gast’s painting, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe had been in existence for only a couple of years and was limited to little more than the state of Kansas. Cyrus K. Holliday, the first president of the line, had a grander vision for the road, and once again it would have to be constructed ahead of settlement. An interesting tension emerges here when Bryant acknowledges the “ecological disaster” of the slaughter of the great bison herd, but notes that the AT&SF made money moving their bones eastward for fertilizer. The Santa Fe entered New Mexico by climbing over Raton Pass; it went on to Las Vegas and thence to Albuquerque. After being distracted by first getting to the Pacific via Mexico, Holliday knew the line would have to reach California directly, and the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad charter would be the key. Bryant also describes how the line expanded southward into Texas, as well as back east to Chicago.

While attempting to claim this turf, Holliday would have to contend with a tough adversary in Collis P. Huntington, the driving force behind the Central Pacific and later the Southern Pacific. This confrontation, in which Holliday eventually prevails, provides a nice segue to the other major transcontinental line of this southern region. The Southern Pacific claimed another one of the five routes roughly charted by the Pacific Railroad Surveys in 1853; it would trace the 32nd parallel, between southern California and New Orleans, and was christened the Sunset Route.

Beyond the history of the lines in this region, Bryant addresses the many ramifications of their presence, which is a major promise of this book. Beyond compressing time and space and bringing settlers and commerce into undeveloped areas, the rail companies worked hand-in-glove with farmers to be more efficient in their practices, which was good for traffic. But the changes brought by the rails were more widespread. With the introduction of the reefer, for example, railroads changed the way people enjoyed food. Due to the marketing departments, architecture and urban spaces were altered, no less. Bryant also relates how the AT&SF hired Hispanics, Native Americans, and women as it moved through its timeline. In the end, for a myriad of reasons, Bryant states, “It is impossible to visualize the contemporary Southwest without considering the past and present contributions of the railroads.” (p. 164)

Contemporary Views

A plethora of images, made during the latter half of the 20th century, grace the pages of the “Modern Views” galleries, one gallery for each of the three geographic regions. There are many stunning works by the likes of Wallace W. Abbey, J. Parker Lamb, Jim Shaughnessy, and Richard Steinheimer, photographers who expertly captured the essence of American railroading between the end of steam and the Staggers Act. The western views curated here are well seen and solidly composed—often with landscape and railroad depicted in perfect tension.

Near Dos Cabezas, California, 1967

De Golyer, Library, SMU

In addition to these now period masterworks, there are outstanding works by contemporary photographers Wayne Depperman, Drake Hokanson, and Joel Jenson, to name just a few. As others have noted, this generation of practitioners cut their teeth in the time period following the New Topographics exhibit at the George Eastman House in 1975. This single exhibit spawned a movement of the same name, which provided for a less expressive way of looking at things. In contrast to the romantic and spiritual way of seeing nature à la Ansel Adams, these photographers began to focus their attention on the clash between nature and culture.

I suspect the Rephotographic Survey Project, conducted by Mark Klett et al. at the end of the 1970s, also got under the skin of these photographers. Klett, himself influenced by the Eastman House exhibit, worked to precisely re-photograph over one hundred images made during the four major governmental surveys of the 1860s and 1870s (named for King, Powell, Hayden, and Wheeler). Some of these historical images include views made along the just completed Pacific Railroad, such as Devil’s Slide, by William Henry Jackson.

Dale Creek Bridge Site

Sherman Summit, Wyoming, 2013

The New Topographics movement was more than a passing fad and is still influencing many of these post-modern practitioners. In particular, see the work of Mark Ruwedel who published his own important book called, Westward the Course of Empire (Yale University Press, 2008), and has many pieces included here. While some viewers may describe these images as empty, clinical, or even banal, others see them as straightforward artifacts with a beauty all their own, which, in the end, may be considered something closer to what we might call the truth.

The Northwest

Hofsommer begins his essay by stating just how revolutionary the railroads of the 19th century were for the United States before diving into his purview, the northern tier. He begins with the Northern Pacific, which was to be built between Lake Superior and Puget Sound according to its 1864 charter. The project stalled until Jay Cooke got involved in 1870. The eastern portion of this construction met the western at Gold Creek, Montana in 1883. The Northern Pacific would have competition from James J. Hill and his road that would become the Great Northern. It took an additional decade to have his transcontinental line completed at what is now called Scenic, Washington. The latecomer to the party, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul, would complete its western expansion at Garrison, Montana, in 1909.

All three roads stressed the opportunities available in the Northwest at that time and offered special fares to encourage settlers; they named towns in such a way as to appeal to certain nationalities. Like the Santa Fe, they worked with farmers to be more productive. The cattle industry helped to provide much traffic beginning in the 1880s. Hofsommer describes how these roads linked the “hinterlands” to urban centers, such as Minneapolis/St. Paul, to create an economic boom. While less impactful in terms of revenue, passenger trains, along with their advertisements, shaped “popular perceptions of the West.” (p.226) To intensify the allure, Jay Cooke petitioned the government to create Yellowstone National Park, while Louis W. Hill, James Hill’s son, then president of the Great Northern, lobbied for Glacier National Park.

Sully Springs, North Dakota, 2013

Hofsommer then describes the slow, but inevitable, path from prosperity to decline for railroads generally, and their eventual revitalization. The largest attack came from public-supported competition; highways become impactful earlier than I would have imagined. After the burst of activity during WWII, earnings returned to a downward trend. The introduction of wonderful streamlined trains would serve as a last ditch effort but was not up to the task, given increasing competition on many fronts. The “age of railways” had passed, but Hofsommer reminds us that, “for much of the nation, and certainly for that gigantic expanse of land from the Great Lakes to Puget Sound, rails had blazed the trail.” (p. 241)

Cognitive Dissonance

To complete the book, Drake Hokanson connects railroads with photography, which grew alongside one another during the 19th century. Hokanson nicely describes the production challenges of the collodion wet-plate process, which most photographers used in the latter half of that century. He goes on to relate how photography morphed and moved forward in the 20th century, including the influence of the New Topographics movement. I had the pleasure of bumping into Mr. Hokanson in the dusty middle of nowhere, during the summer of 2012, where we both were working to capture something of the near-nothing that remained of the Central Pacific between Lucin and Promontory Summit.

In the end, the rich and textured essays, paired with stunning and well-optimized imagery, provides for a book with the appropriate gravitas for the sesquicentennial of the Golden Spike, and the reflection that it demands. May 10th 1869 was a watershed moment in this nation’s history. The first transcontinental railroad was a monumental engineering achievement that pierced the sublime and opened the West, which drove settlement and economic development. Alfred A. Hart was not averse to using titles for his works to convey the importance of what was unfolding during the construction. Advance of Civilization: End of Track Near Iron Point, taken in the midst of a vast and desolate Nevada, is not hyperbole. The building of the Pacific Railroad, and the subsequent transcontinental roads, described in this book, contributed to this economic development and united a vast nation.

And while all of this is true, some of us also see, with cognitive dissonance, the other side of the coin. This might include the beginning of the end of the West as frontier, discrimination against the Chinese workers who performed so well for the Central Pacific, and conflict with indigenous peoples that led to the Indian Wars. While dwelling on the positive, After Promontory does not shirk its duty to touch on this other side, which is often left only to the imagination.

Richard Koenig

Genevieve U. Gilmore Professor of Art, Kalamazoo College

Copyright 2019

After Promontory:

150 Years of Transcontinental Railroading

Hardcover, 10X10, 320 pages – color and B&W – $50.00

§

Click Here to Order Your Copy

Thanks to Scott Lothes, Executive Director of the Center for Railroad Photography & Art for his cooperation and assistance in preparing this article.