Henry Theodore Wilhelm was born in 1905, in the middle of arguably the most exciting and constructive decade in American history. The Panama Canal, electrification of mainline railroads such as the New Haven, huge new steel bridges and other infrastructure improvements, all were part of investment in America and her future. The list of what was deemed possible, and then doable, goes on and on.

At age 14, Henry became fascinated with railroads, and especially with the thousands of manned interlocking stations and cabins. This led to his lifelong hobby of documenting these unusual places, which the railroads had built as a necessity for preventing collisions, given the high volume of trains transporting passengers, mail, and freight all across the country. Over time, he photographed more than 2,500 junctions and the towers that controlled them. His notes were precise and detailed, and his negatives individually numbered and described in his log books.

Following graduation from college, Henry took a job in engineering, working for the Bell Labs division of AT&T in New York City, and then suburban New Jersey. Fortunately for us, he applied his remarkable talents in photography, logistics, organization, and enthusiasm to embark on a lifelong hobby of photography that is a pleasure to all of us reading The Trackside Photographer.

Henry was what we today call a “railfan,” and his records and photographs are a treasure trove of railroading history that can be shared electronically with others. Henry died in 1986, and so did not enjoy the benefits of the internet, but I am sure he imagined it happening in the future and would have loved it. After all, he was working at Bell Labs.

There are around 7,000 black and white negatives in the Wilhelm archives. During one of his railfan adventures, Henry met and befriended a 14 year old enthusiast on a 1947 New Haven Railroad fan trip from New Haven to Maybrook New York, over the famous Poughkeepsie Bridge. Henry and his new young friend were both standing in the vestibule of the last car, where Henry was taking notes of mileposts, sidings, and especially signals. The young boy thought this an interesting exercise, so he started taking notes, too. Henry became a mentor for his new friend, Dick Carpenter and together they shared many other railroad adventures over the years. Later, Dick Carpenter created and produced a remarkable set of volumes of meticulously hand drawn maps of the entire United States as the railroads were in 1946, published by The Johns Hopkins University Press. https://www.amazon.com/s?k=richard+carpenter+railroad+maps&ref=nb_sb_noss

Henry’s documentation of railroad structures, scenes, stations, and of course trains, included meticulous notes and records of every photograph, including file number, railroad, tower designation, town and state location, and date. Much of his work was done between 1927, when he was twenty two, and 1939, during which time he met, courted and married Margaret Mitchell. The couple continued to travel extensively, always with notebook and camera at the ready.

They also had a son, Alec, and when Henry passed away in 1986 at age 81, Alec gave this collection of negatives, drawings, and records to Dick Carpenter, who in turn donated them to the National Railway Historical Society affiliated SONO Switch Tower Museum in Norwalk, Connecticut, with John Garofalo as custodian of the material.

People emerge from the shadows, and we can only wonder what they were thinking when they saw Henry with his camera.

I have been digitizing images from slides, glass plate negatives, prints, and B&W negatives for more than twelve years, and have now completed more than 104,000 images. So when John asked me for help in scanning Henry’s original negatives, I enthusiastically agreed.

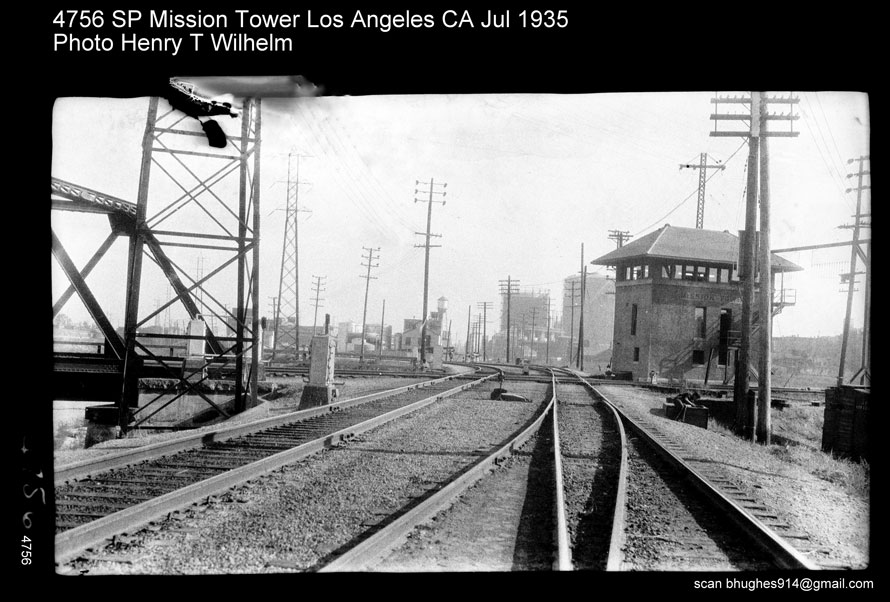

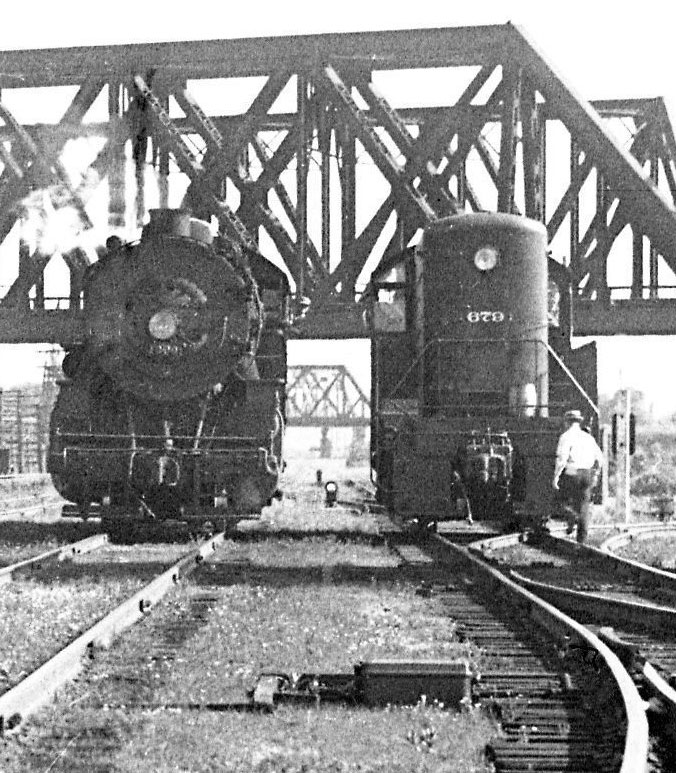

Here are some examples of the structures and the people which Henry so diligently photographed, made possible through the wonders of computers and scanning technologies, which Henry would have loved.

The photographs are remarkable not just as a record of the railroad signal towers which were found in great abundance, protecting virtually every switch, diamond crossing of different lines, junction and station. Some were taken after driving to often remote locations, and many others were taken from Henry’s favorite place to ride—standing in the open vestibule of the last car of his train, recording the network of switches, signals, signs, stations, and of course, towers and people as they receded into the distance.

But the photographs provide much more than an architectural record of the towers. Steam engines and the railroads they ran on, with frequent stops to resupply water, coal, and to lubricate the countless moving parts of the locomotive, were very labor intensive. Track maintenance was performed by gangs of twenty of more men, not by sophisticated machines operated by a skilled operator working in air conditioned control cabs.

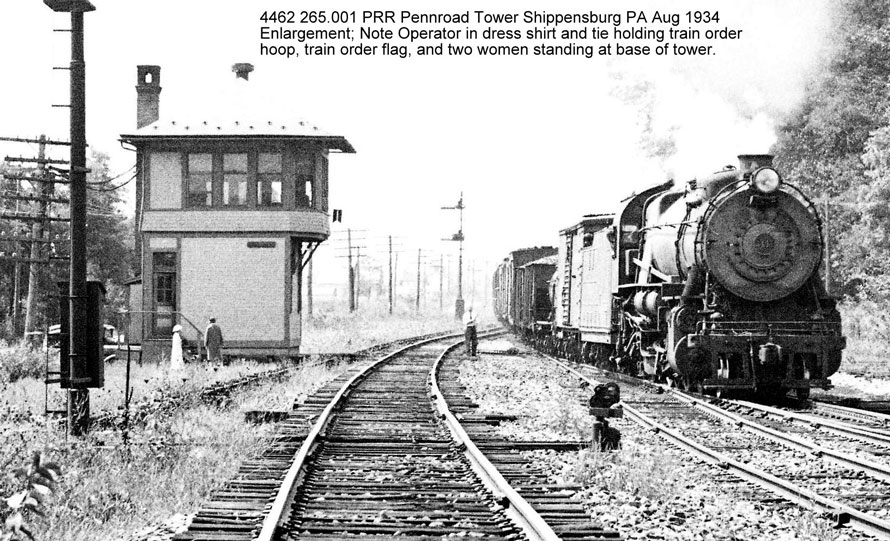

It is these people, often not even noticed in the photo until after the negative has been scanned (I use 1200 dpi settings for B&W negatives) and enlarged on the computer screen who make the photos so fascinating. People emerge from the shadows, and we can only wonder what they were thinking when they saw Henry with his camera. Who is that guy with a camera taking a picture of the tower when there is no train around? Why does anyone want a picture of ME? It is a fascinating record of railroading in the era from after World War I and through World War II, which Henry Wilhelm’s photos and Dick Carpenter’s Railroad Atlas document so thoroughly.

Here are some examples of the structures and the people Henry so diligently photographed, made possible through the wonders of computers and scanning technologies, which Henry would have loved. We are very fortunate that the collection exists to provide such a wonderful view of life, and of railroading in the United States as it was one hundred years ago

A nice ride with the top down, visiting Erie Towers!

Tracks, signals, and a Tower with no trains

Mom and three daughters in their Sunday best for an after church visit to Dad in his tower

Train leaving Eastview on a sunny summer day

Steam engine, Diesel Engine, Tower and Yard, Seneca NY

Two proud engineers wanting to be in the photo of their cabs

Signal Cabin on the LIRR – Cold on the winter nights!

Union Pacific Station from rear vestibule of departing train

Enlargement with conductor’s salute and baggagemen with cart

Passengers awaiting their train, grouped with other travelers

Tower A – Pennsylvania Station before the station’s destruction.

PRR Pennroad Tower with train and signals

Detail of operator, engineer, and lady friends who have joined a summer outing chasing trains

Signal Cabin on ACL with operators expected to wear suits and ties

Notice the tower, operator, automobile, and oncoming train…

To impress your railfan boyfriend, stand next to a speeding doubleheaded steam train in lovely summer dress and white high heels!

Easy to miss the two people behind the left telephone pole if you are watching the oncoming train!

Bike, car, and foot traffic resumes once the gates go up

OK boys, let’s get these switches cleaned

Marine traffic has the right of way

Ready for the most famous train, the Twentieth Century Limited, on the New York Central

Keep the camera at the ready for the most interesting train and watch for interesting things from that rear vestibule

The records and photographs made by Henry Wilhelm and many others comprise a wonderful view into railroading and railroaders, and deserve to be preserved for history. If you decide to scan your images, either your own or others, you’ll derive great enjoyment from your work and learn things you never knew about railroads in the last century.

Bob Hughes – Photographs and text Copyright 2019

Excellent!

Great work! Are any other of his images available online, or will they be? Thanks.

Dan, some images can be found on North American Interlocking, and as the article says, there are about 7,000 images in total. Each one takes about 20 minutes to scan, position, correct exposures, add contrast and balance, then label with file details and name. Finally, it can take another 20 minutes to go through the image to remove minor specs or dirt from the scan. Time consuming, but well worth the effort.

Forgot to add the link: http://northamericaninterlockings.com/

Thanks, Bob. Some of the images are from where I grew up, and others from where I live now. Thanks for taking the time to scan and post them.

If you ever find a photo of Glendale, CA tower (where the PE crossed the SP mainlines) I’d love to have a scan, all for personal reasons. I grew up in a house a block from the tower and as a kid was there a lot. The operators let me throw some levers…..armstrong but I could move all but No. 2. PE line shut down in June 1955 and the tower closed in January 1957 after automatic gates were installed.

Alan Miller

ALAN,

Glad to see you on here.I wonder where that ACL Florida location is.

Joseph, here’s info about Carbur https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbur

Alan, I’ll make a note to look for Glendale. I know there are California scenes that have not yet been scanned.

Bob, it is, indeed, diligent work to scan older negatives. In my experience, a decent scan can take more than 20 minutes with a medium format film scanner. And retouching blobs and scratches with Photoshop’s heal tool – well, 20 min, 30 min, often 45 min.

Dan, I might add that we are planning to publish another group of Wilhelm’s images on The Trackside Photographer next month. Edd Fuller

Thanks, Edd.

Thanks for sharing!! Wonderful!!

You’re spending 20 minutes retouching every scan, but only scanning them at 1200dpi?

Replied earlier, but it did not go through. Yes to 1200 dpi; I did numerous tests at 300 dpi, 600 dpi, and 2400 dpi, and settled on 1200 dpi. Higher resolutions did not reveal more detail, since the original B&W film is 90 years old. Each negative is 120 format roll film, measuring 4.25 inches long by 2.5 inches wide, and takes between two and three minutes to scan this size at 1200 dpi. Scanner histograms then allow five different adjustments to correct under/over exposure, contrast and density. The retouching can be tedious, because some of the negatives contain up to dozens of blemishes (usually tiny white dots, not apparent to the naked eye) which can only be removed one at a time without changing the original photo.

Appreciate these photos. They could have been taken by my dad, a “train nut” , later a ” feroequinologist”or “lover of the iron hose. We saw a lot of our are by going with him to get in the right spot to photograph a certain train.It was great fun and we learned a lot,too.When I see these pictures It immediately brings dad back.

Don’t know who you are (anonymous) but if you are in the Northeast, I might have photos you would be interested in. Bob. bhughes914@gmail.com

Thanks for info on Carbur.AFAIK the plant is still running.

Great story Bob, thank you so much for taking the time to do this and share them. You brought to life some things in the pictures that would not have been noticed

Great story, well written, and a nice “ slice of Americana”!

Heartwarming memories of a time gone by.

Thanks to all involved in this Project. I really like seeing the western images, esp. LA and Mission Tower, since that’s my home zone. But all of it is a veritable treasure trove.

What an wonderful story and an incredible treasure of a bygone era.

Great article and greater photos Bob…I especially LOVED the tower shots.

Dan Maners

Thanks Dan. All the scanned images have been sent to John Garofalo, and I know he intends to submit tower shots to you for your website. I enjoyed writing the narrative, and scanning/correcting all the negatives. What a fascinating story these photos tell. Bob.

Thank you for a very interesting story. I find the last photograph the most interesting to me. It appears to show the M10000, Union Pacific’s (and America’) first lightweight, articulated, internal combustion passenger train. After it’s initial grand tour, and display at Chicago’s railroad fair, it went into service as the City of Salinas, running between it’s namesake and Kansas City. Being constructed of aluminum, it was sacrificed to be recycled (into aircraft?) in WWII.

A very interesting story of the bygone era of the Iron Horse and it’s various train stations thru out our country. The time and process to extract the photographic images from negatives is just an amazing process. I have enjoyed seeing this today and I hope there will be more.

Thank you for sharing this story with me.