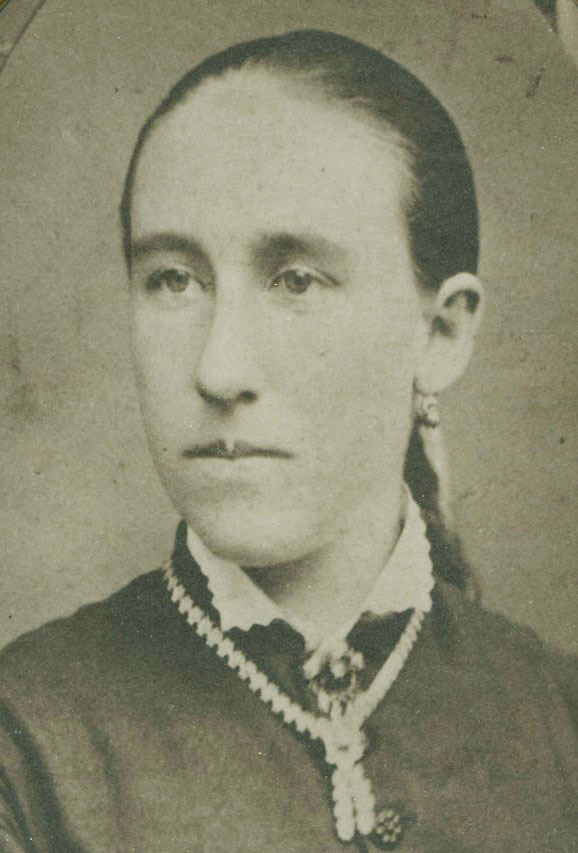

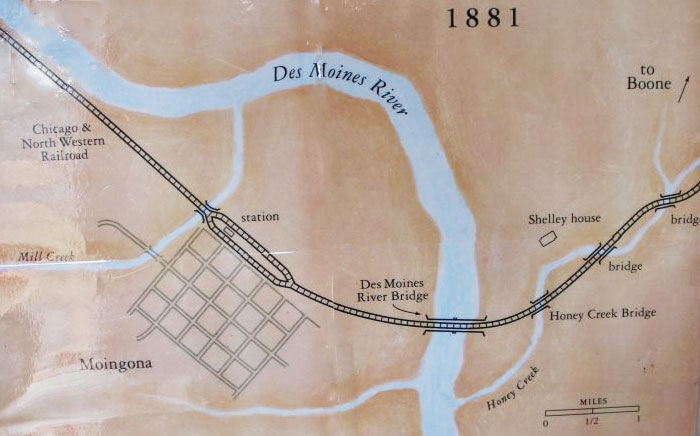

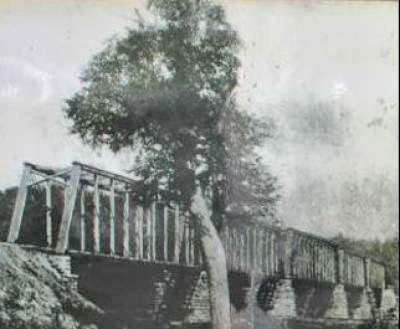

On a stormy summer night in 1881, 17-year old Kate Shelley crawled across the Des Moines river bridge in the dark to warn the approaching Midnight Express of the collapse of the Honey Creek bridge. She became a legend. This is part two of her story. Part One is here.

A New Mainline

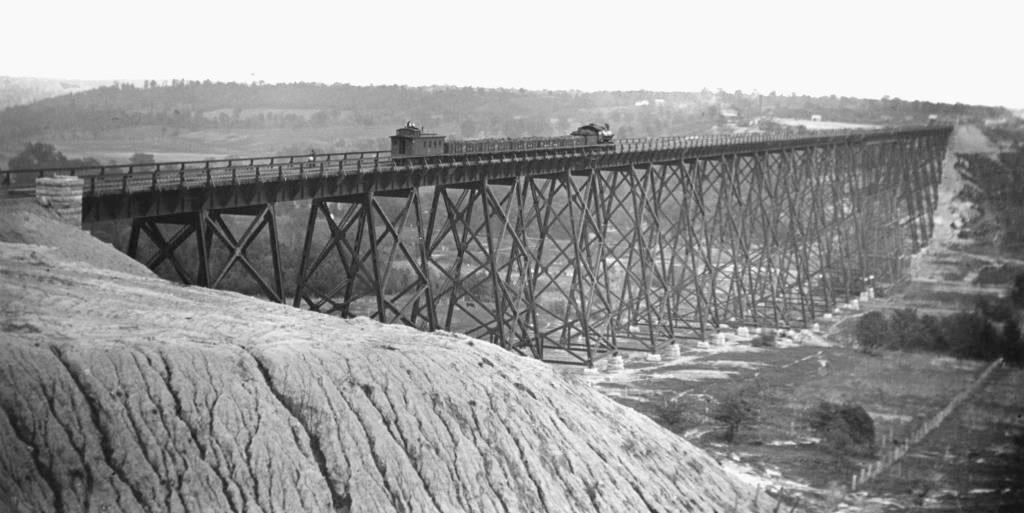

Some 18 years after the dramatic events of July 6th, 1881, the Chicago & North Western Railway began construction on a new high tech mainline located several miles north of the Shelley Homestead, near Moingona, Iowa. This new cutoff was part of a multi-year project to rebuild the highly important mainline between Council Bluffs and Chicago. Construction of the portion through the Boone area began in 1898, and work on a new viaduct over the Des Moines River began in 1899.

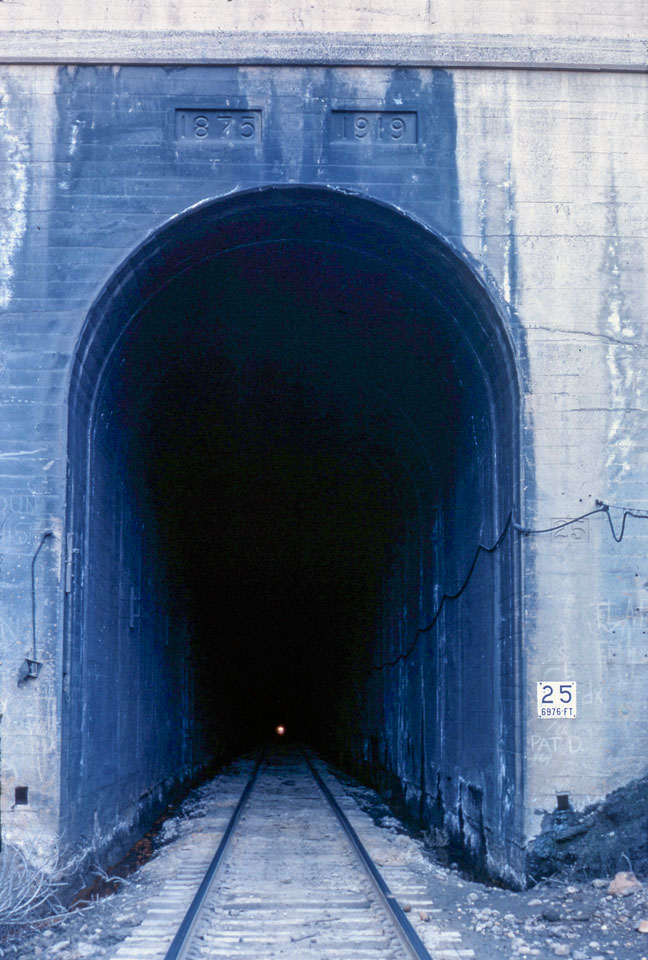

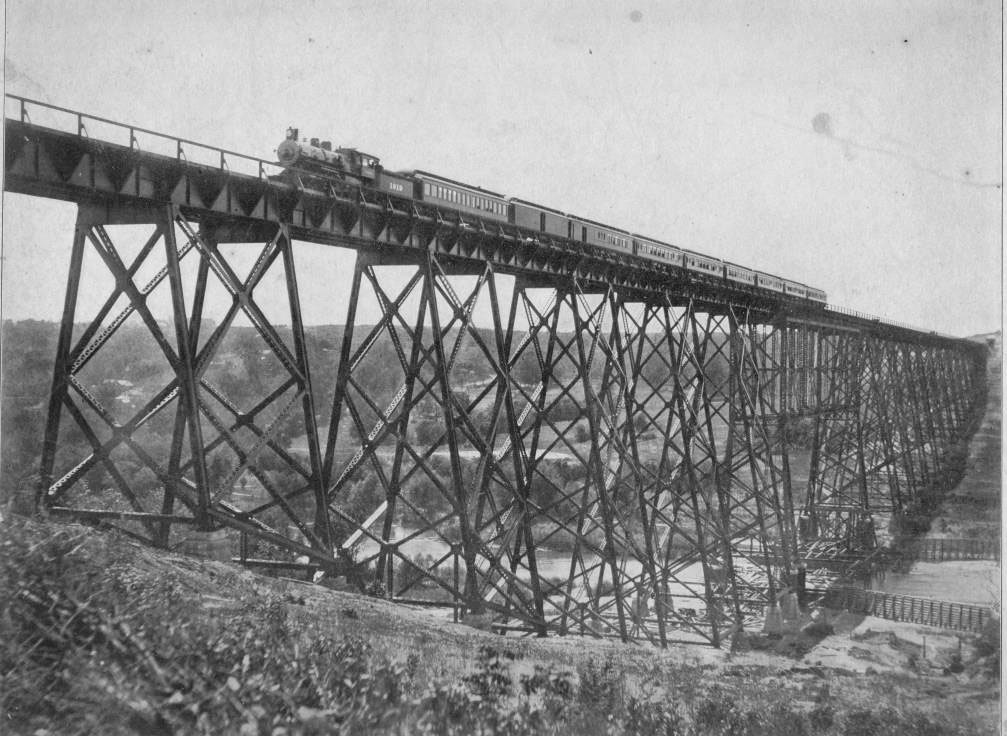

In early 1901, the new cutoff opened to traffic. The highlight was a half mile long, 185-foot-high viaduct over the Des Moines River. Originally referred to as the Boone Viaduct, it gradually became known as the Kate Shelley High Bridge, as a tribute to the young girl who saved the Midnight Express in Moingona. The viaduct was engineered by famed engineer George S. Morrison, and was one of his final projects. Both American Bridge Company and Union Bridge Company supplied the structural components for the bridge. At 2,685 feet long; it is still regarded as one of the largest double track railroad bridges in the world. Soon after the new line was opened, the Moingona line was downgraded to a branch line.

Despite the constant attempts by the railway to hire her, Kate oftentimes had other jobs; working at the Iowa State House as menial labor, or as a school teacher in the area. However, Kate finally took the job of station agent in Moingona. She remained unmarried through her life, despite the interest of coworkers in the area. Her mother died in 1909, and she stayed with her brother, John, who also worked for the railroad. In 1910, Kate’s health began to fail. She had some brief stints in hospitals, before returning to Boone County, where, in September of 1912, she succumbed to Bright’s disease.

In 1930, the Moingona line was removed in preference of the Chicago & North Western route north of the area. All traces of the line were removed, including the Honey Creek Bridge that had collapsed and set in motion the events of that night in 1881, and the Des Moines River bridge that Kate Shelley crawled across in the dark to save the Midnight Express. The remaining artifacts included the 1901 depot, which replaced the original structure that burned the same year, a stone arch in Moingona over Mill Creek, and several miles of railroad grade.

Over the years, Kate Shelley became a legend in the area. The Chicago & North Western designated a train from Chicago to Omaha as the Kate Shelley 400. The name was created in 1955, and removed from service in 1971. Boone County created a museum at the Moingona station, called the Kate Shelley Railroad Museum. The portions of the rail bed around Honey Creek and the Des Moines River are footpaths for those seeking to follow in the foot-steps of Kate’s heroic run in 1881. The Boone Viaduct, while never officially renamed the Kate Shelley High Bridge, still stands and can be visited very easily. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. In addition, a number of documents pertaining to Kate and her family are in a special collection at the Iowa State University Parks Library.

The Kate Shelley High Bridge

In 2006, after 105 years of use, a project began to replace the High Bridge near Boone. Chicago & North Western was purchased by Union Pacific in 1995 and the Union Pacific continued to use the line to full capacity. The new bridge opened in 2009. At 190 feet high and 2,813 feet long; it is larger than the old structure. This bridge was officially christened as the New Kate Shelley High Bridge. In 2016, the old structure is closed to trains, while the new concrete and steel structure carries the traffic. Side by side, the two bridges create one of the most impressive spectacles in Iowa.

Epilogue

While Kate passed away over 100 years ago, her legend and story is one of the most inspirational and common stories passed to children in Iowa. At college in Ames, Iowa; I was hard pressed to find a student who grew up in Iowa not knowing the story of Kate Shelley. The two high bridges off Juneberry Road between Boone and Ogden attract tourists, rail fans and history buffs alike. While the new bridge oftentimes serves over 100 trains a day, the old bridge has been closed since 2009. It is hoped that it can someday become part of a memorial walkway. One would find it very difficult to visit Central Iowa without at least a glimpse of the legend of Kate Shelley.

John Marvig – Photographs and text Copyright 2016

See more of John’s work at John Marvig’s Railroad Bridge Photography