Lamenting the loss of a classic PRR signal—

The Position Light

Like many other essential railroad technologies, signaling developed with the need to manage the ever-increasing frequency of trains safely as railways expanded in the 19th century. As companies grew they adopted various solutions, but by the first quarter of the 20th century, standard designs began to evolve, and suppliers became valuable assets to the rail industry. Union Switch & Signal and General Railway Signal became two of the most common names in American signaling. They offered stock solutions that railroads could adopt and apply to their given network, but also catered to larger roads who sought to develop proprietary designs. The more recognizable wayside signaling was of course only a fraction of the full signal system. Behind the scenes, relay cases, code generators, interlocking towers, CTC machines and dispatching offices were all tethered to miles of cable and track circuits. This complex network communicated the vitally needed information to their endpoint – the signals, that familiar line-side icon of railroading as we know it.

After World War II signaling developments continued to evolve, but to the casual observer, much of the visual character of a given railroad’s signal system remained the same. When American railroads entered their crisis years, highlighted by the disastrous Penn Central, these signals preserved the identity and heritage of a fallen road, enduring mergers, acquisitions, even abandonment. For many of us, these signals have become objects of affection, oft-sought props in photographs as a respectful nod to a specific road and technology that was lost before our time. Today, that technology is rapidly disappearing with the Federal mandate for railroads to install Positive Train Control. PTC is bringing a significant visual change to rail corridors, removing lineside signals except for interlockings and replacing familiar vintage systems with the homely “Vader” type LED signals. The former Pennsylvania Railroad territory has been no exception; the classic PRR Position Lights are falling rapidly across what NS calls its Premier Corridor, the storied main line from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh. Fortunately, not all is lost, as Amtrak and SEPTA continue to employ modern adaptations of the PRR’s classic design.

While creating images for the Main Line Project, I have focused on the landscape and surviving infrastructure of the once self-proclaimed “Standard Railroad of the World.” Though I never explicitly set out to preserve signals in detail, they have always been a significant visual element in making photographs of and about the PRR. I am pleased to present here a brief history of the PRR’s classic signaling design, accompanied by a curated selection of images. These photographs chronicle the various installations of PRR’s Position Lights and associated interlockings where appropriate, and represent an important aspect of the PRR’s surviving vernacular and engineering legacy. The loss of these signals may forever change the look and feel of the beloved Penn, but we can only work to preserve what still stands, as the rail preservation community has been doing for years.

The Position Light – A Brief History

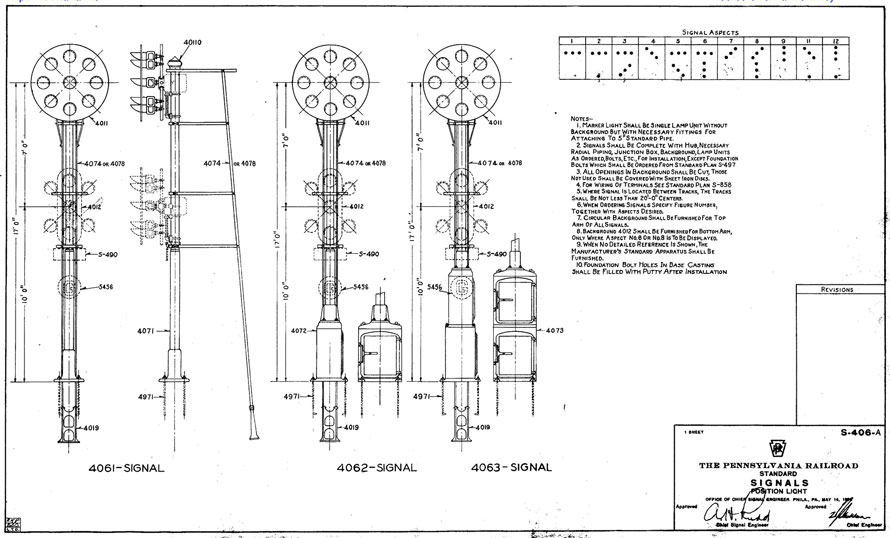

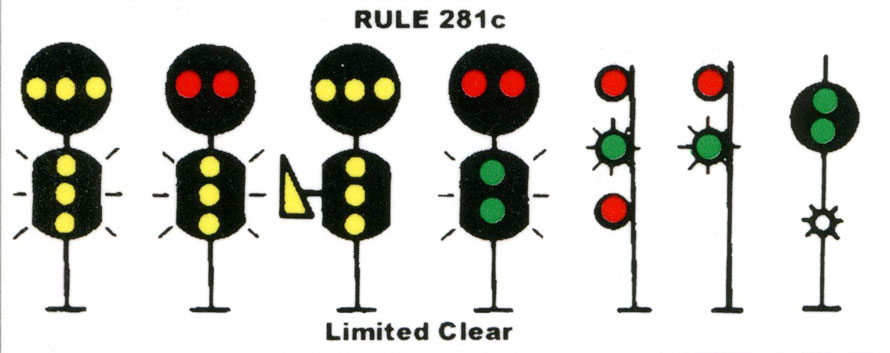

The Position Light signal, an iconic trademark of the Pennsylvania Railroad, first went into service on February 14th, 1915, between Overbrook and Paoli, on the fabled Philadelphia Main Line. The brainchild of PRR Chief Signal Engineer Alexander Holley Rudd, this preliminary design, coined the “tombstone” signal, was a prototype of what would eventually govern most of the PRR’s signaled territory by World War II. Rudd was looking for solutions necessary to eliminate the previous standard, maintenance-intensive semaphore signals. Not coincidentally, the initial installation of these prototype signals accompanied the railroad’s first phase of 11,000 volt AC overhead electrification. Their design and placement were shaped by the visual range changes and obstructions created by the addition of overhead catenary structure and line side support poles. Rudd’s use of a series of lights to mimic the position of a semaphore not only significantly enhanced night time and foul weather visibility but also reduced maintenance by eliminating moving parts and saved money, employing a highly efficient housing to focus low wattage lamps. The signal’s design used two “arms” (a reference to its roots in semaphore signals) the upper arm to display permissive signals (automatic block signals) combined with a lower arm to display speed signals (absolute signals). By 1921 the PRR’s Position Light design used only three lights per aspect and was evolving to become the standard model of signaling throughout most of the PRR system.

Consequently, the Penn was not the only railroad to utilize Position Light signals; a bitter rival, the Baltimore & Ohio, introduced its iteration of the Position Light as early as 1920, a design patented by L.F. Loree and F.P. Patenall. One of the first significant installations of the Color Position Light signals (CPL) was on the Staten Island Railway, at the time a B&O subsidiary. Though the general concept of aspects utilizing multiple lights was the same, the PRR and B&O designs were entirely different. From the perspective of the lamp design, Rudd collaborated with Dr. William Churchill of Corning Glass who was working to address headlight deficiencies of western railroads, where extended range illumination was required. Their design employed a carefully focused wide angle lens using a small low wattage bulb combined with a fog-penetrating yellow glass. Additional elements in its design included an intermediate device called a Phankill that prevented external light from infiltrating the enclosure, eliminating false indications by reflection. The B&O signals employed a simpler colorized lens design; the primary signal target was similar to the PRR’s, utilizing three lights in each position. However, the common, or center light is eliminated, leaving two green for the vertical pair, two amber for the right diagonal pair and two red for the horizontal pair. There was also an option for two lunar white lenses for the left diagonal where needed.

To indicate speed control aspects orbital lights accompany the B&O Position Light signal, located in one of six locations above and below the target. The combination of the orbitals and primary target conveys speed instructions in both the first and second blocks ahead. The PRR’s signals conveyed speed aspects utilizing a lower “arm” or quadrant, which ranged from a full target (consisting of vertical, left and right diagonal, and one center light) to any variation that a particular installation required. Most all parts for both PRR arms were standardized, making components completely interchangeable. While the debate raged regarding color indications vs. the PRR’s pale yellow, Rudd’s design addressed invaluable crew complaints that the colorized indications performed less favorably in low light and inclement weather. He even argued that a color blind engineman could accurately decipher the PRR’s signal indications. Despite differences between the PRR and B&O, redundancy was the ultimate benefit of both designs, allowing for multiple lamp failures before a signal would fail, and incorrectly display an indication.

The Position Light design served the Penn well and went largely unchanged after 1921. Significant design changes included the development of the early and later models of the slow speed dwarf or pot signals. The “new” redesign switched the rounded edge of the signal toward the track, providing more clearance to keep larger equipment from clipping the signal and providing enhanced access to the lamp assemblies. Another notable development was the introduction of the pedestal signal, which was capable of displaying a full range of aspects like the standard Position Light design, but fit in tight spaces where clearance was an issue. The signal employed a simpler short range 2-light per aspect, 2-arm indication layout instead of the three lamps used on traditional Position Lights. Some sources say this particular design was a product of the Philadelphia Improvements Project during the late 1920’s through the 1930’s where clearances were extremely tight in the dense terminal. The last notable change in the PRR, Penn Central and even early Conrail era was the introduction of red lenses in the stop aspect, which replaced the traditional yellow lights in signals protecting interlockings.

Come the ill-fated Penn Central, the fate of PRR Position Light designs would take divergent paths as the PRR system evolved into new independent operations. Design & maintenance of signaling on the Northeast Corridor and mainline to Harrisburg went to Amtrak, while the mainline west of Harrisburg and connecting lines in the Northeast fell to Conrail and ultimately Norfolk Southern.

Norfolk Southern’s Pittsburgh Line

Perhaps one of the last bastions of classic PRR Position Lights was on what Norfolk Southern now calls its Premier Corridor: a high-density railroad laid out in the 1850s by the first chief engineer of the PRR, visionary leader J. Edgar Thomson. In addition to the PRR’s original Main Line, this corridor includes the Columbia & Port Deposit Branch and Trenton Cut-Off among other lines that provide connections along the Northeast Corridor.

Despite the implementation of bi-directional signaling and the closing of most interlocking towers early in the Conrail era, the route retained much of its PRR character. The line still employed several towers into the 1990’s, dispatching trains over the busy mountain grades east and west of the Allegheny summit in Gallitzin, Pennsylvania, and many wayside signals along the route. One significant change came as a result of double stack clearance improvements in the mid-90’s, spelling the end for most of the remaining towers, and a handful of signals protecting these interlockings. C Interlocking tower in Conemaugh, SO in Southfork, MO in Cresson and AR in Gallitzin all lost local control, and many of the Position Light signals that protected the home limits of these critical interlockings fell too. Shortly after that, Conrail itself vanished, split between CSX and Norfolk Southern, the latter assuming control of former PRR Main Line.

The Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008 set in motion the final blow to the remaining PRR signals, requiring new signaling and communication installations system-wide. NS petitioned the Federal Railroad Administration in 2012 for the elimination of all automatic block signals on the Pittsburgh Line in Train Control Systems (TCS) territory; trains would now rely solely on cab signals except at interlockings. While enthusiasts may lament the loss of traditional signaling, Rule 562 is not exactly a new idea. The Pennsy operated the Conemaugh Line as early as 1940 solely on cab signaling outside of interlockings between AJ Interlocking at Kiski Junction and JD Interlocking in Conpitt, a system that still operates today under Norfolk Southern.

With the impending PTC, NS tackled that last major challenge left by the PRR and its predecessors—reconfiguring and remoting ALTO tower’s territory—on June 16th, 2012. The $6.3 million project eliminated the last remaining manned tower on the Pittsburgh line, which controlled five interlockings in the Altoona terminal area. By 2014, work was progressing rapidly up the Port Road, and material stockpiles began to grow in earnest at strategic points including Enola Yard near Harrisburg and Rose Yard in Altoona. Over the past year, signal crews have been working at a fever pitch, moving west from Enola, systematically removing what remains of the PRR signal system, a significant visual asset of the former PRR Main Line.

Amtrak

Interestingly enough, Amtrak’s former PRR properties remain a stronghold for the Position Light design but look carefully, not all are what they seem. Amtrak began converting PRR Position Light signals to color light signals as early as the late 1980’s. Today they are known as Position Color Light signals, to differentiate them from the B&O’s Color Position Lights. Built on the same premise of having redundancies to provide fail-safe signaling, the modern signals utilize incredibly bright and efficient LED lighting. One could speculate this is a direction the PRR might have taken had they still been around. Like NS, the railroad is slowly eliminating wayside signals as they systematically implement an advanced cab signal and train control system known as ACSES (short for Advanced Civil Speed Enforcement System).

ACSES, a precursor to PTC, is not a new concept on Amtrak; it was first implemented along with the electrification between New Haven and Boston to increase maximum authorized speeds up to 150 MPH with the introduction of Acela equipment. The Keystone Corridor, a highly successful State funded operation between Philadelphia and Harrisburg, PA is also undergoing a significant overhaul implementing (to date) ACSES between Park (Parkesburg) and State (Harrisburg Station). Ironically, the other half of the line between Park and Zoo is one of the last remaining examples of a PRR Main Line circa the late 1930’s. You can still admire a nearly-complete PRR railroad; trademark yellow Position Light signals, PRR stations, two eras of electric traction infrastructure including two 1915 substation buildings and to top it off the line still employs several manned towers. Yes, the role of the interlocking tower is still a part of operations, with Zoo, Overbrook, Paoli, and Thorn, still governing traffic 24 hours a day.

While some of the imagery here depicts signals and interlocking installations that remain in service, many are going fast. Whether you are on Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor or the NS mainline across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, be sure to take a moment and get your images of original PRR signaling and infrastructure while you can, even if there are no trains present. These classic PRR position light signals have now long outlasted the company they were built to serve, yet in varied ways shapes and forms, they have continued to govern many trains under the banners of the Penn’s many successors. One can only wonder if the signal designs implemented with PTC can last over 100 years like the PRR’s venerable old Position Light, or what the next step will be in the progress of railway signaling. Today, we can only document the disappearing past and look to the future for what is to come.

Author's Note: I would like to thank the many people who helped with this article. Your input on both technical and editorial aspects was critical to the success of this piece. I would also like to note; all images featured in this article where track access was required, were made with proper permission and protection with the appropriate railroad officials. I do not condone any behavior that may risk your safety or the welfare of others. We should all be out documenting the railroad, but please stay off the right-of-way!

Michael Froio – Photographs and text Copyright 2017

See more Michael’s work and his blog Photographs & History at www.michaelfroio.com

Click on the image to open in viewer.

Very interesting & informative

Michael:

Masterfully done, both your written words and exceptional photographs. And yes these are ‘photographs’, not just pictures or snapshots. I admire your work, the use of large format film cameras and brilliant well thought out compositions. And in black/white – which speaks to me even more.

Your last sentence says it all, not only for the PRR position lights, but all aspects of the railroad landscape from a disappearing bygone era.

“Today, we can only document the disappearing past and look to the future for what is to come.” Well said.

Great to see your work featured here!

Matthew

You’ve neglected to mention why the original 4 light Position Lights were deservedly called “Tombstone Signals”. When you find a photo or two notice the out of service, but still in place, two position electro-pneumatic Union semaphores on the nearby bracket masts. And why do you youngsters always leave out the Hall Switch & Signal Company, The Federal Signal Company and the predecessors of G.R.S. (National, Pneumatic etc.) and those of US&S?

Alas, you teenage types also have no thoughts or comments on the beauty, yes the outright visual superiority over any light signal, the aesthetic delight of the form and color of semaphore signals. A mere handful of which are still in service in northern New Mexico.

Some 40 years ago as you are now bemoaning the “loss” of these, I felt the same about the once ubiquitous semaphore signal. So as a dude in his mid twenties I went out and “saved” several examples. I expect you to do the same with these.

Michael, very nice work. I like the drawings of the signals, nice touch.

Exceptional ! Thx Michael, from an old PRR into PC into CR signalman. Note Figures 5 & 6 were for searchlights and color lights also.