Steve Crise is a professional still photographer and lighting designer based in Los Angeles, California. His love of trains led him into photography, and his work has been featured in Railfan & Railroad, Trains, CTC Board, Railroads Illustrated, Model Railroader’s four articles on Rod Stewart’s HO scale layout, and annual report work for the BNSF and Union Pacific. He teaches each February at the Nevada Northern Railway on the basics of night photography using his electronic strobe equipment. Steve is active in several organizations devoted to the preservation of railroad history and has traveled widely to document the remaining traces of our railroad heritage.

Edd Fuller, Editor, The Trackside Photographer – Steve, shortly after I started The Trackside Photographer, I wrote to you asking if you would be willing to write for us, and we subsequently published a great article by you called “Macro vs. Micro.” I want to thank you for that, and for taking the time to talk with us about your work. Although you are a professional photographer with clients in many different fields, the railroad seems to be at the heart of your work. How did your love of railroads come about?

Steve Crise – I’m not entirely sure how my interest in railroads came about but legend has it that I used to cry in my car seat at the Southern Pacific’s Fletcher Drive crossing when my mother would often get stuck at that crossing. Her accounting of the situation would have you believing that I hated those noisy trains, but I think it was more about not being able to see them well enough from three car lengths behind the gates. Whatever it was that lit the flame it has stuck with me all these years. And to add fuel to that fire, it seems as though just about every Christmas I received some sort of toy or model train as a gift. Wooden trains, plastic trains, Marx, American Flyer, Tyco—it goes on and on. Aside from the modeling, I used to draw and paint a lot when I was a kid. I always had some sort of project going on. The American Flyer was always set up around the Christmas tree and once we moved into a larger home, I was allowed to build a small HO layout. The layout added to my interest in real trains because naturally I wanted my layout to look as real as possible.

So slowly I considered the use of a camera to record things I would see on weekend trips and adventures. As I got older, I did not ask for a gift for my birthday, but instead, I would ask to go to places like the Tehachapi Loop or the Trolley Museum in Perris, California, to see the real trains in action. In August of 1967, I hit the jackpot when my family took a cross country trip on the Santa Fe to Kansas City to visit relatives. I think I stayed up the entire two days I was on the train just looking out the window and either drawing or photographing things I saw that passed by my window. I still have the color negative of the Santa Fe RSD 5 I shot through the window of the train while it was stopped in what I recall being Clovis, New Mexico. That trip sort of started it all. And thankfully my mother was very generous with the use of her Kodak Brownie and I proved to be at least adept enough to frame things decently that I was entrusted to shoot some pictures of the folks we visited on our trip. At this point in time I was still doing better with my paints and pencils then I was doing with a camera, and my teachers were always encouraging me to draw and paint more landscapes and city scenes, so for most of my youth I was pretty certain I was going to have some sort of career in art. Although there is a very funny side note to this. In 1964, I was one of those guest kids on Art Linkletter’s “House Party”. It was sort of the original mid-afternoon show for housewife’s that interviewed special guest celebrities and the like. Perhaps “Ed Sullivan Lite” is the best way to describe it. In any case I was chosen, along with four other classmates of mine, to be a “kid” on the show in which Mr. Linkletter would interview us toward the end of the episode. He’d ask the usual questions, like “what do you want to be when you grow up”? I enthusiastically answered “I want to be an Engineer on the Railroad when I grow up”. I didn’t exactly pronounce my R’s correctly; they sounded more like W’s and got a laugh out of the audience. I still have the 78 RPM audio recording of the show that they gave us kids as a memento of our visit.

Edd – You have written that your interest in railroads led to your interest in photography. Tell us about how you got started as a photographer.

Steve – I seriously thought I was going to be an illustrator or something along those lines. The camera thing was just sort of always there but I never considered it seriously as a profession. When I entered 8th grade, my art teacher somehow arranged a scholarship for me for Junior High School students at the Art Center College of Design, which in the late 1960’s was still on 3rd Street in Los Angeles. I went to weekend classes at Art Center where I studied, among other things, packaging design, lettering, transportation design and life drawing with real nude models! That was a lot to digest for a thirteen year old, but it was really great, because there was also a photo studio at the college that I would visit before and after my classes started. There I watched students lighting and shooting all kinds of projects for their classes. It was like learning the secrets of how all the photos in magazines and catalogs were made. It was very inspirational experience.

I finally received my own camera for my 9th grade graduation present. It was my very own Kodak X-15 126 format camera. And the first thing I wanted to shoot with it was trains, hence another trip to the Orange Empire Trolley Museum in Perris. By now I was transitioning quickly from drawing to photography . . . well, as quickly as anyone could shooting with an X-15 anyway. Summer jobs afforded me the purchase of an Olympus FTL 35mm single lens reflex camera, the poor man’s Pentax, with interchangeable screw-mount lenses. This was a quantum leap forward: control of exposure and focus provided me lots of opportunities to experiment. About this time I also became more aware of the names of the photographers who were making the images that I wanted to emulate, and they weren’t only the names found in the pages of Life or Look magazine, but also in Trains magazine and in the pages of the Golden West Books that I would sometimes get as a gift at Christmas. After a while, I could see the unique styles and approaches that each photographer had developed and could spot their work without having to read the credit line.

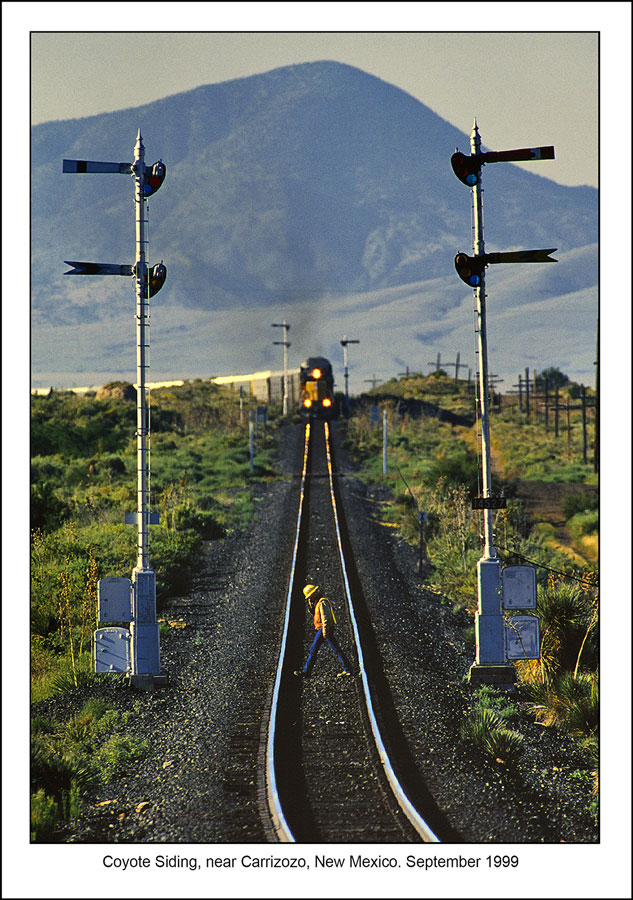

As I entered college, preparing myself for a career in the art business, I was required to take a beginning photography class, and so I did. I excelled in it without much effort, so I went on to the next level of study to see if perhaps this was something I wanted to pursue. As it turns out, I switched majors and went on to major in photography. During this period at college, a job opening became available at a studio in Hollywood that catered to the entertainment business. I applied and got the job, never finishing school. I didn’t see the need to since I was in the thick of it now. I learned more in six months of practical experience than I could have at four years of schooling. So I was off and running and shooting railroads pretty much got lost for a while. It was also pretty obvious that shooting nothing but trains and railroads was not something that you could make a great living off of unless you were employed by a railroad, and those jobs were few and becoming fewer in the 1980’s. It wasn’t until much later in my career, mid-1990’s or so, that I started working as a freelance photographer for railroads. Shooting railroad subjects before this time was more a part of my off hours endeavors. I started doing freelance work for the Union Pacific in the late 1990’s and then for the BNSF starting around 2005. These have been some of my favorite assignments, but they have also been some of the most challenging. It is quite a different experience going out on a Sunday afternoon to casually shoot along your favorite line for a few hours and go home. It’s generally not important if you got what you were going after or not, there are no consequences for failure. When you’re being paid to get results, the pressure is really on you to perform. Generally we are working to a shot list that is provided by the client. There are a number of items we need to shoot both with video and still cameras. This can include trains but often times there are also employee and customer interviews that are part of the assignment. We work in all kind of conditions, all kinds of locations from diesel shops to in Alliance, Nebraska to isolated mainline locations in California. Occasionally we’ll utilize a helicopter to assist us in telling the story. These are some of my favorite assignments. There’s nothing quite like chasing a speeding freight train in a helicopter!

Edd – At a young age, you came to know Donald Duke and became involved with the Pacific Electric Railway Historical Society. Tell us a bit about this connection and how it influenced your work?

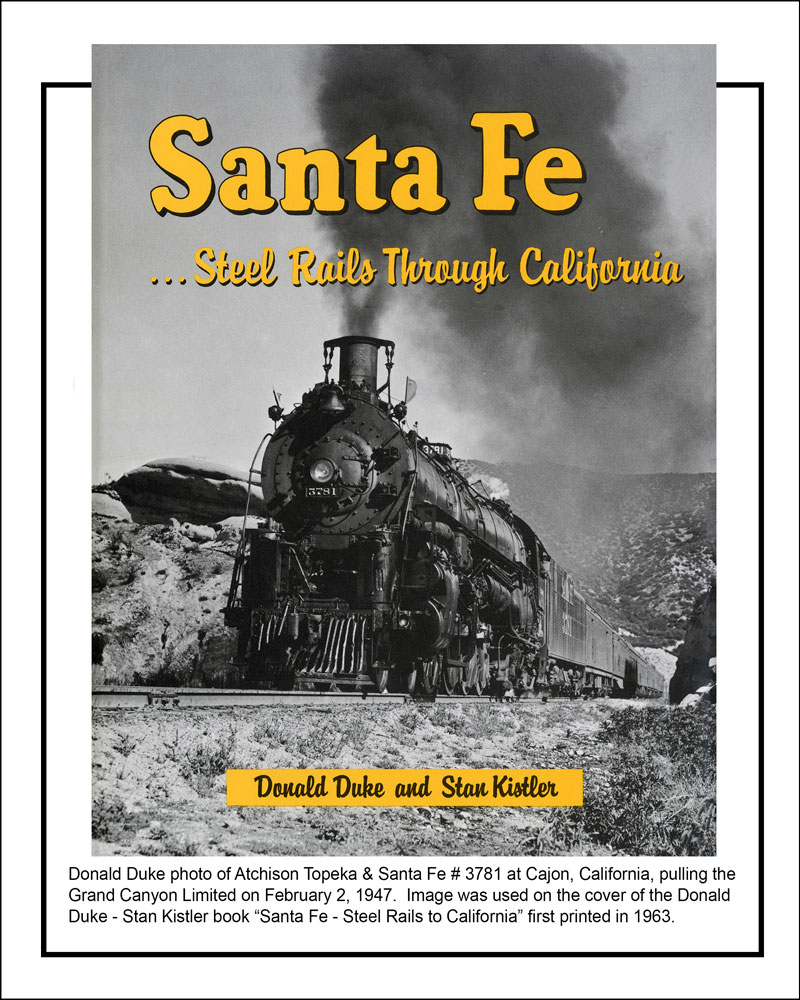

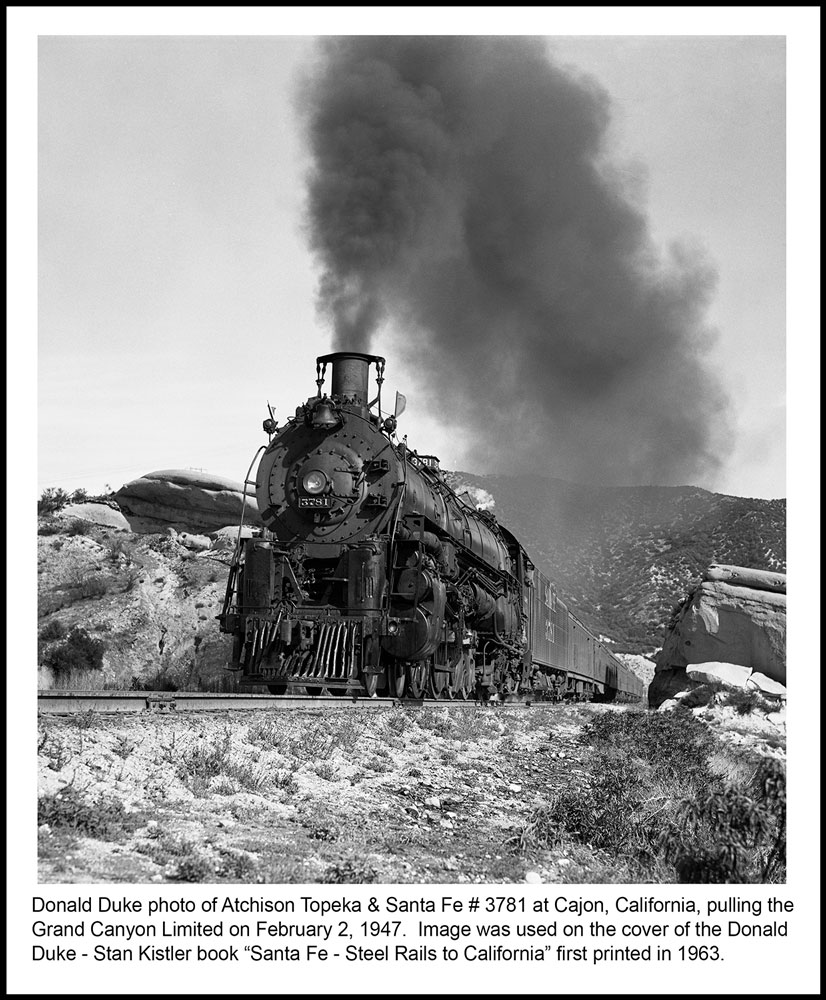

Steve – I first came to know about Donald Duke through the pages of the many books that he either authored or published. In particular, his pictorial on the Pacific Electric, simple titled “PE,” with an illustrated cover by E. S. Hammock. It was a collection of works by many different photographers, Don included, illustrating the Pacific Electric, not as a historical accounting, but as a pictorial. Originally published in 1958 under his first publishing company Pacific Railroad Publications, the soft cover had 14 or 15 printings so there’s a ton of them out there. It was the first purely photographic railroad book I owned—and it was about the mysterious and legendary Pacific Electric Railway, the interurban railway that just seemed to have completely vanished one day in 1961. As a young boy I had always heard about the PE and could still see traces of it all around if you knew what to look for and where! So from this first purchase, I continued to be a consumer of Don’s Golden West Books for many years. My interest in the PE and the history of Los Angeles and its surrounding communities made many of Don’s publications a necessary item to have in my library. I didn’t actually meet Don until the late 1990’s and I eventually had an office in his building on Electric Ave, a very appropriately named street for his business. One of the great aspects of Don’s work was his ability to capture a scene in which the main subject and its environment seemed to fit together perfectly; one was never overpowering the other. Don was also one of the early action shooters with his big giant Graflex D 4 x 5 camera. The focal plane shutter in that camera could freeze the action of a fast moving train – no problem at all. Don was never a roster shooter, he liked the dramatic action shots. He was also the publisher of sports and athlete books. Don had covered the Olympics both in Germany in 1980 and in LA in 1984; not very many people know that about him. This perfectly explains his love of action photography with both people and trains.

Dons’ legacy of Golden West Books still lives on today under the guidance of Michael Patris. The business has relocated to a new facility in Pasadena where we are still turning out new subjects on the Pacific Electric and other railroad related subjects. We have a series of monographs on the Pacific Electric that we are currently working on, with two titles that are finished and published and with a third title that is being put together right now.

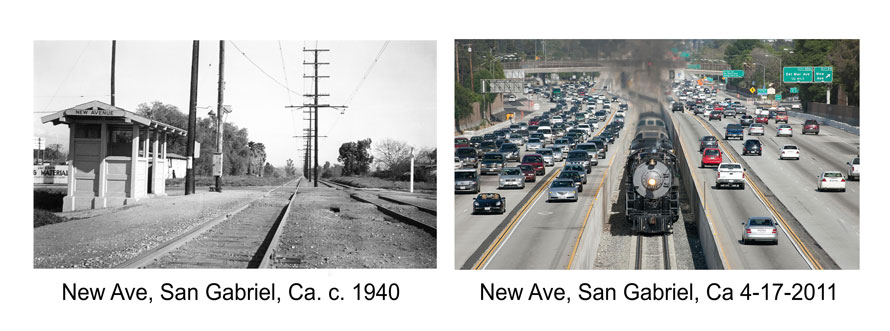

Edd – I am intrigued by your “then and now” work, mixing historical images with contemporary photographs. From your perspective, what does this approach teach us about the past in relation to the current culture.

Steve – Generally speaking, I don’t believe our public schools here in Los Angeles are doing a very good job with the teaching of history—American, Western Civilization or local history. I’ve run into many examples of this personally. I thought that by taking a subject that is all around, familiar streets and boulevards, and showing them as they were, it would be of interest to people, especially young people, and it usually is. While shooting this project, I’ve had many people, young and old, all races and colors, come up to me and ask “what am I taking a picture of?” I usually respond by simply showing them the historic images of the area I have brought with me to match my shot. Most people have a hard time believing there was ever a trolley or trains running down the middle of their street. Most people have no idea what life was like before they were born and most don’t care. But some actually take that experience of seeing their neighborhood as it once was to heart and become interested in the other details within the historic image. For example, the auto and trucks are usually the first things that are noticed, then it’s the fashions of the people in the historic photo, or the price of gasoline, or the type of people or ethnicity of the neighborhood at the time. The subject of T&N is inescapably political by its very nature. People always muse to me or themselves about “What the Hell happened?” “How did it come to this?”, usually not said in a positive light. Another example is that when I lecture about the PE Then and Now images, many people have mistakenly come to the conclusion that certain large American corporations systematically killed off the PE and other transit systems. This was not the case with the PE. The final blow was actually dealt by a publicity agency that advocated bus service over rail service. Perhaps this was done with good reasons in some cases, particularly with the lines that were unprofitable or that had street running that made it impossible to maintain a reasonable schedule. But the urban legends about the PE and other LA transit systems have been around so long, everyone accepts them as fact. I have to admit that I was a firm believer of the legend myself. I never gave it another serious thought until I did the T&N books. Things are not always as they seem.

Edd – The railroad has played an important role in the history of the United States, and your work reflects a deep interest in that history.

Steve – Well, there are many facets to railroad history. I think that’s why it has held my interest for such a long time. I’m just studying and sharing a very small portion of that history in a way that I hope will be helpful to someone in the future. One positive aspect of the T&N books is that it has given people the incentive for discovering LA’s old transit systems for themselves. I’ve had people come up to me after a lecture and they tell me they had picked a location in the book and went out and to see it and photograph it on their own. That was really nice to hear.

As a youngster I was enthralled with the stories of my uncles and grandparents; their photo albums were windows into their world seventy, eighty years before my time. It gave me an appreciation of their lives. It’s the same way with old photographs of the city. I appreciate the hard work of the generations who came before me; it only seems natural to do this sort of thing as a small homage to their efforts. I can only hope that something I do or create while I’m here can add to the life and enrich the experience of someone in the future.

Edd – There is currently a (perhaps somewhat faddish) interest in what has come to be known as “urban exploration.” In 2016, you were featured on an episode of the TV documentary “Lost LA” titled “Lost Tunnels” about the abandoned subway tunnels in Los Angeles. The story included a young photographer who I think would fit the description of “urban explorer,” who claimed he did not care to know about the history of what he was seeing. As a photographer, where do you find the balance between the artistic possibilities of a subject, and interpreting and documenting its historical significance?

Steve – I remember when this was called Urban Spelunking. At any rate, I don’t understand how one can go exploring the grimy innards of a city’s tunnels and not wonder why they are there. When we were kids, we would sneak into all kinds of places, tunnels included. We just didn’t make videos about it but we sure as hell wondered why those tunnels were there. Perhaps the only way an individual can make him or herself stand out in a crowd these days is to make their discoveries public by use of social media. I’m sure at some point their curiosity will get the best of them and they will start to investigate the history of these places.

What we try to do with the T&N books, and I say we because Michael Patris and I co-authored these books together, is that the subject matter we choose for the studies be as familiar a location as possible. Some of the locations we choose you can see from your car or by walking down the street. This makes it part of the viewers personal daily experience. It’s a personal connection to their day to day, perhaps monotonous, journey that they have made thousands of time before on their way to work or home, which they can appreciate in a brand new way. That building on the corner of Pico Street and Vermont Ave has been there since 1906! It still has the original gargoyle over the front door! We love to use images that have that sort of connective quality to them. On the other hand, we will sometime use an image that bears little or no resemblance to its present day counterpart. These are fun images to do as well, but use too many of them and you can cause your reader to lose that personal connection you are trying to create with the viewer. In one instance we used an old Pacific Electric car as the T&N featured subject. PE 1001, one of the old wooden cars that still survives today was shot at its present home at the Orange Empire Museum to match a photo if the same car in service in 1939 in San Pedro, California. So there are more than a few ways to illustrate a Then and Now image. It’s a balance we are always having fun with. I’m not sure I would call what we’re doing with the Then & Now studies “art”. Maybe on a few occasions we get lucky and something beyond their original intent to just illustrate our changing environment comes through in a special and meaningful way, but that’s generally not our goal with these images, it’s a bonus if that happens, but it is not our intent.

It’s one thing to have the opportunity to shoot a subject, it’s quite another to properly take advantage of all the possibilities afforded to you.

Edd – Perhaps this is a good place to discuss your work with the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely, Nevada. [Click here for NNRY video featuring Steve] Since 2006, you have produced night photo shoots for the NNRY. Tell us about these shoots and your involvement with the NNRY.

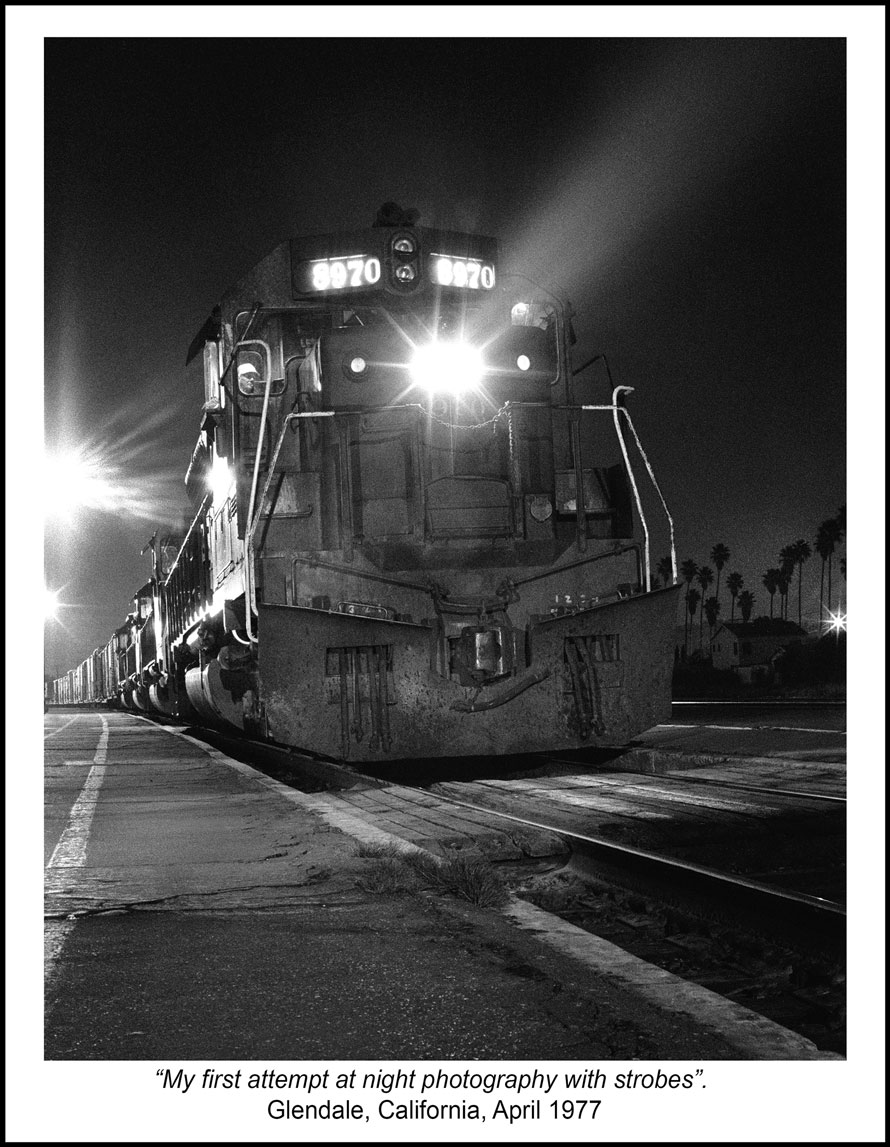

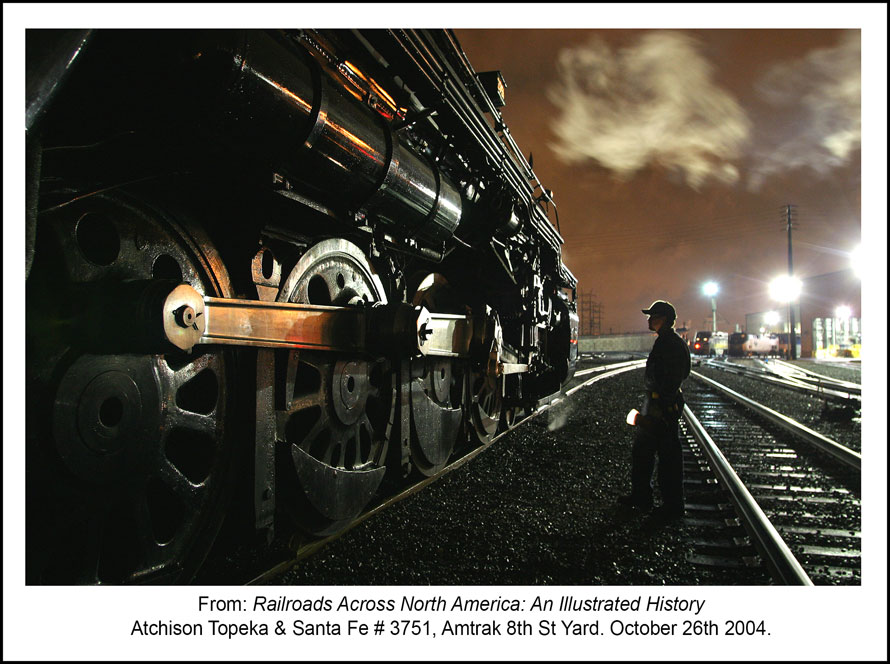

Steve – Prior to 2005, I wasn’t that much involved with doing large scale photo shoots of steam locomotives at night. I really didn’t pursue this type of photography very much at all. I had done some personal night photography work with the AT&SF 3751 as a crew member starting in 1999, but nothing that was formally organized where tickets were sold. I don’t recall exactly how it all came about, but in 2005 I was asked to produce a night photo shoot for the Grand Canyon Railway for an excursion they were running and billed as perhaps their last steam run for a while. Since I didn’t use flashbulbs or hand held flashes for these types of set up shoots, I was able to give the photographers a lot of “bites at the apple” since the strobes recycle rather quickly and frequently. The repeatability of these lights gives photographers the chance to try different views and exposures. Lots of experimentation can happen in one evening. Generally speaking, we can shoot upwards of fifty to seventy-five exposures per session. This was a big improvement over the other two methods. Word got to the Nevada Northern about this kind of strobe lighting and Mark Bassett, president of the NNRY, asked me if I would be interested in doing a night photo shoot for him at Ely. I agreed and I’ve been going back there two or three times a year ever since. I’m on my thirteenth year now in 2018.

During these past dozen plus years Mark has really grown the experience at the railroad and has come up with some really great new attractions at the NNRY besides the Winter Photo Freights. I’m involved with two of these new events, “Steam, Steel & Strobes Scholarship” and “Nevada Northern Photography Workshop” (http://www.nnry.com/pages/photo-workshop.php). “Steam, Steel & Strobes Scholarship” is basically a contest we have where younger photographers between the ages of 18 & 30 submit 3 images and a short essay for review. Mark and I decide on four winners, two first place winners who receive free admission to the Winter Photo Freights, lodging in Ely and a $500.00 travel stipend. The two second place winners receive free admission to the Winter Photo Freights, lodging in Ely, and a $250.00 travel stipend. We had the largest response to date this year with over 30 entrees. Our idea here is get younger people interested in photography of steam railroading and give them a chance to hone their skills without breaking their budgets. “Nevada Northern Photography Workshop” will be a three day intensive study and shooting program that I will be teaching along with Mike Massee. It’s limited to only 15 people. It combines classroom lectures and hands on shooting around the NNRY yards and facilities. We’ll go out on the line to help you with capturing the best images. There will be instruction on strobe lighting with strobes and a night photo shoot. Mike and I will be on hand all three days to help and answer any questions you may have while shooting. We think this will be a great experience for both the intermediate and experienced shooter.

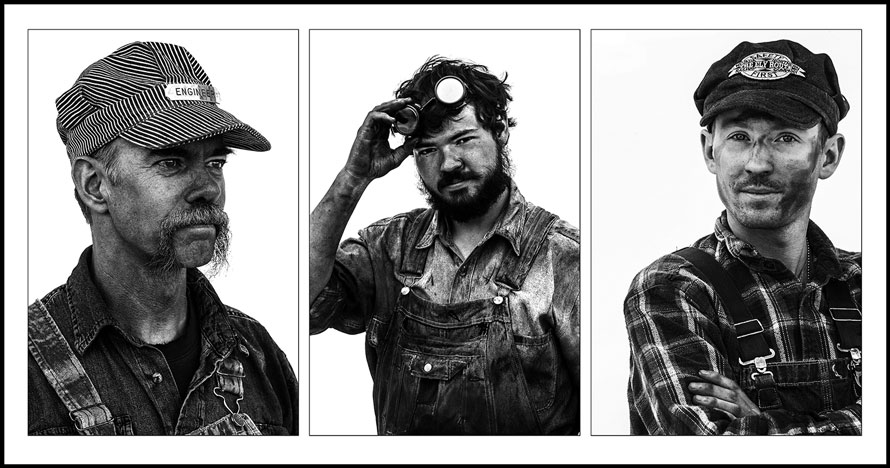

My personal work at the NNRY has been concentrated more on portraiture of the steam crews and shop personnel then on the equipment or locomotives. My inspiration for this was very slow in coming. Although I had always tried to make portraiture of railroad employees an important part of my work, I didn’t have the opportunity to really dig into it until I got to the Nevada Northern. In 1985, Richard Avedon’s exhibition and subsequent book titled “In the American West” was released. It was a groundbreaking study of portraits he shot of coal miners, drifters, waitresses, mental patients and prison inmates throughout the American West from 1979 to 1984. It was a startling and disturbing discovery for me as a young photographer. I was both repelled and attracted to these graphically stark, disturbingly beautiful photographs. Many of the characters contained in his book seemed to come to life for me during my first visit to Ely in 2006. The idea to emulate this type of portraiture floated around in my head for another decade until I was burnt out on shooting the railroad equipment. Finally, in 2015 I started to re-trace Avedon’s steps in my own small way. Forty years after seeing his stunning and revealing works, I began my homage to the working railroader emulating his style. This effort has become the main focus of photography for me at the railroad. Although part of the allure of Richard Avedon’s work was his decision to use an 8 x 10 view camera, I’ve had to adapt his techniques to fit in the digital world we now live in. The set up for shooting the type of portraiture Avedon produced for his book requires no lighting equipment other than a white paper backdrop and a fill card or two. It was exactly the opposite type of set up I had been doing for the night shoots. It’s been a great departure from the complicated sculpting of light with strobes to the use of simple open shade lighting. This effort has yielded some positive results. My wife Yoko and I curated a show of my photography and her paintings at the Orange County Fine Arts Gallery in Santa Ana, California. Yoko’s paintings of the Nevada Northern’s rolling stock and my portraits of the crews were shown together in an exhibit titled “Portraitures in Steam”. This show was up for a year at the NNRY’s depot waiting room as well. Oddly enough, we had better sales of our work in Ely Nevada than we did in Orange County California.

Edd – As a rule, portraiture is an area that is neglected by many railroad photographers, so it is great to see your work in this area. I particularly enjoy the fact that your subjects are seen in context– in their working environment. How do you approach this work? Any advice for those of us who would like to include railroaders in our work?

Steve– I agree with you that portraiture is very much neglected in railroad photography. My theory is that the simple task of capturing a train or locomotive is the most basic step in railroad photography. I think a lot of people simply stick to the basics and make a lifetime of creating this kind of art, and there’s nothing wrong with that. My problem was that after I felt that I knew how to capture a locomotive or train on film fairly well, I felt as though all my pictures started to look the same. Basically I got bored and wanted to try something else with my photography. Maybe that was the genesis of my night work as well, I simply got bored and wanted to try something new. There is a different kind of drama you can create at night. Sometimes you find the light is already waiting there for you to discover, other times, like at the Nevada Northern and other venues, I have to create the drama with the lights that I bring with me. I just finished my 13th year producing night photo shoots for the NNRY Winter Photo Freights event. These are typically very large scale lighting projects and can get a bit complicated. We do involve models in these shoots but they’re not typically the focus of these shoots, they are more like set dressing to add scale and reference. The size and scale of these types of night shoots and the lack of attention it offers to the human element is yet two more reasons I wanted to do something less complicated lighting wise and that would dramatically emphasize the people that work at the Nevada Northern rather than the equipment.

Edd – In the book Railroads Across North America: An Illustrated History, you are quoted saying “Cold weather, damp air and darkness make for great steam railroad pictures.” Aside from the technical challenge of night photography, what is the appeal of photographing trains at night?

Steve – The appeal is that after the sun goes down, everyone else has usually gone home and you have the subject matter all to yourself. The other aspect is that the light sources are so varied and come from so many different angles and directions, the haphazardness of it all can be better than anything you could have possibly planned for. The trick is being aware of the different points of light and how best to take advantage of them. It’s one thing to have the opportunity to shoot a subject, it’s quite another to properly take advantage of all the possibilities afforded to you. In college we had an assignment in photo class that was titled the Ten Transparency Test. The assignment was that you had to pick one subject for a studio shoot, usually a still life, and shoot ten different and interesting views with your 4 x 5 camera and studio lights. It’s really a great exercise because it’s something you’re called on time and time again by clients to do as a professional photographer. A lot of the techniques I’ve developed as a professional photographer I’ve grafted into my railroad work. It’s really no different than shooting anything else.

Edd – In general, what are the elements that you look for in a good photograph, be it steam, diesel or the structures and landscape that surround the railroad?

Steve – I look for basic shapes, circles, squares, triangles, etc., within the frame and how they interact with each other as a composition. Size and distance relationships are just as important too, and of course light and shadow. This is where a lot of knowledge of art history is helpful. Painters throughout history had to master perspective drawing and understand how shapes within shapes can draw, push and enhance the eye to the main theme of the work. Photography is no different. If you read nothing else in this article, please read and understand this one simple fact; do not live by just shooting railroads alone In order to expand and enhance your visual language skills, you have to expand your vocabulary by shooting other subject matter. Learn and borrow from others. A great way to do this is to study the masters of the Renaissance. You’ll find no better examples of the most extraordinary use of perspective, light and shadow than you will find by studying these works. I just spent all day at the Prado Museum in Madrid this summer with my wife studying their collection of works. A single day really wasn’t enough, but that’s all the time we had. I hope to use what I’ve learned from that adventure in future projects, railroad subjects not excluded.

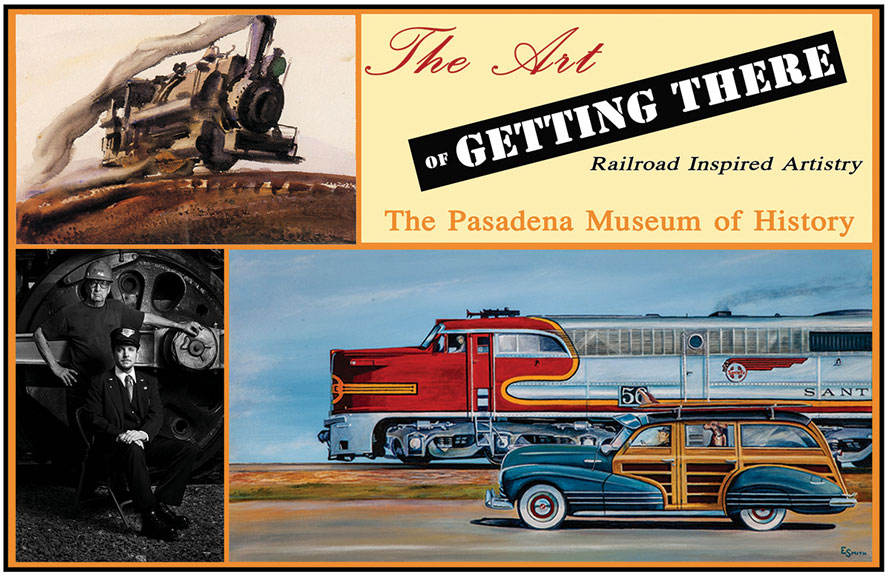

Edd – Last year, you co-curated an art exhibit at the Pasadena Museum of History called “The Art of Getting There: Railroad Inspired Artistry.” The show included works of artists and photographers. Tell us how you approached the selection process, and how you found common ground between painters and photographers.

Steve– Lucky for me you put this question after my speech about Renaissance painters.

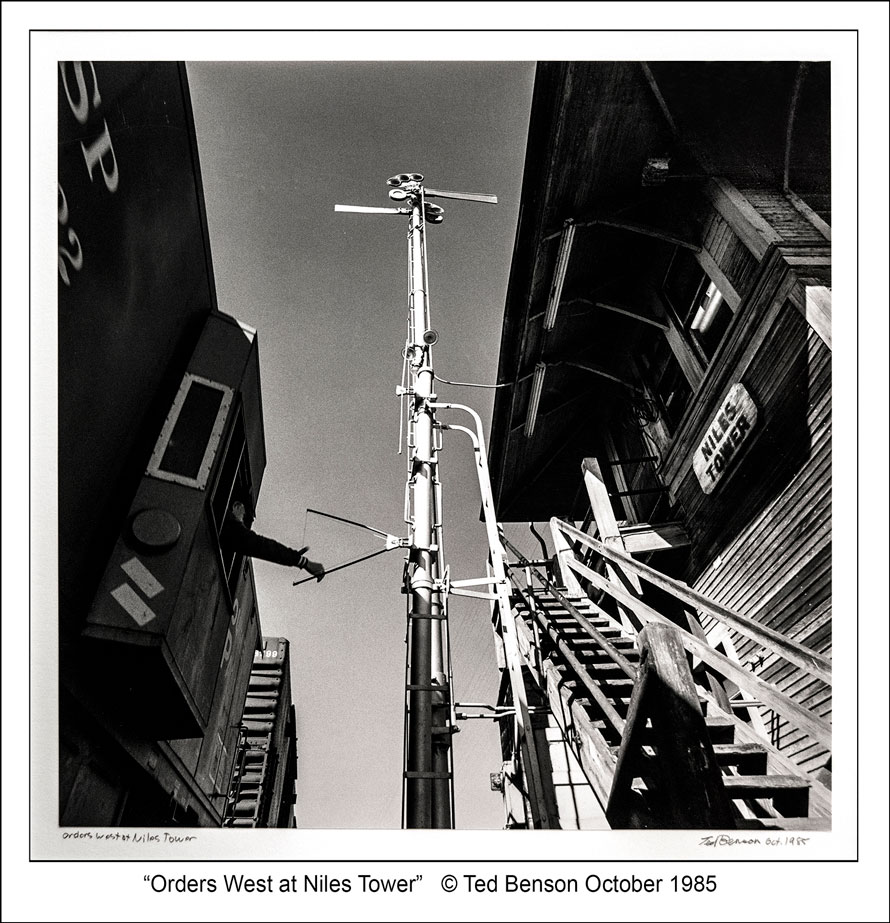

I co-curate these shows with Michael Patris, who is my co-author on the Then & Now projects as well. We had done another show for the Pasadena Museum of History in 2013 based on our book The Pacific Electric Then & Now, and the show was exactly that. Basically color enlargements from the pages of the book with some three dimensional transit related items and printed material displayed alongside the prints. In discussing the approach and concept of “The Art of Getting There” we decided early on that we wanted to expand beyond the confines of just using Southern California based images so that we would be able to examine a large scope of rail history and travel. With that goal in mind, we set out to locate some early works of rail images to give the show a good span of time. Fortunately I knew of a collector of late 19th century Japanese wood block prints and had photographed his collection for a portion of his collection book project. His next book effort was to concentrate again on Japanese wood block prints but this time depicting the arrival of railroads in Japan in 1871. We were graciously allowed to borrow four works for the show and these turned out to be among my favorite pieces. Private collectors that we were associated with also opened up their homes and made it possible for us to display works from the likes of Sam Hyde Harris and Raymond Loewy. Another great source for the show was oils, water colors and pastels that were on loan from the renowned collection housed at the Hilbert Museum in Orange County, California. From the Hilbert Museum we were allowed to display over a dozen works from artist such as Emil Kosa Jr., Jack Laycox and Bradford J. Salamon. My wife, Yoko Mazza, an accomplished painter in her own right, was also featured in the show with four of her own original paintings. We also were able to include some more familiar names from the railroad art world from our own personal collections such as John Winfield, Howard Fogg, John Signor, Harlan Hiney and Eric Smith. Photographers in the show included Donald Duke, Ted Benson, Frank J Peterson, Matthew Malkiewicz and myself. I think we had over forty-five different artists represented in the show with almost every kind of medium represented too. We had several wood carvings and reliefs by Jackie Hadnot. One piece he carved of the Santa Fe Super Chief weight three hundred plus pounds! It was incredible the support we received when we went out trying to procure pieces for this show. And of course the biggest challenge of them all was the arrangement of all these pieces so that they told a cohesive story. The best way I can describe this process is that it lies somewhere between architectural planning, page layout and set design and construction. But perhaps to answer your original question on how we found common ground between painters and photographers, it is best explained by the simple fact that they all shared a common subject – railroads and travel.

Edd – How do you find the balance between your professional commitments and your more personal work?

Steve – Well Edd, you’re assuming that I actually find a balance. As a freelancer, I’m always juggling between too little work and too much. You simply have to get used to the ups and down. When I do have some free time and choose to spend it around railroads, I use the time to look for unusual views, angles and lighting to experiment with for possible use in future assignments. I don’t always have the luxury to search for new possibilities on the job so railfanning has become more of a laboratory for experimentation that has no deadline attached to it. If I spend a few hours at one attempt at an image and retain some useful new ideas, I feel that it was time well spent.

Edd – Outside of photography, where do you turn to recharge you creative batteries.

Steve – My wife and I do a fair amount of gallery hopping. As mentioned before, we devoted a day of our vacation at the Prado Museum in Madrid, another day traveling to the Dali Museum and home, and an afternoon at Museu Picasso de Barcelona. I draw a lot of inspiration from the classical painters. I’m not much of a post-modernist so I tend to stay away from most contemporary art museums. I’ve co-curated two shows for the Pasadena Museum of History so I feel it is somewhat important to see what’s going on in that world, both good and bad. I also rely heavily upon books to help me arrive at some of the concepts I use on assignment. This sort of thing has helped me a lot with shooting both prototype and model railroads.

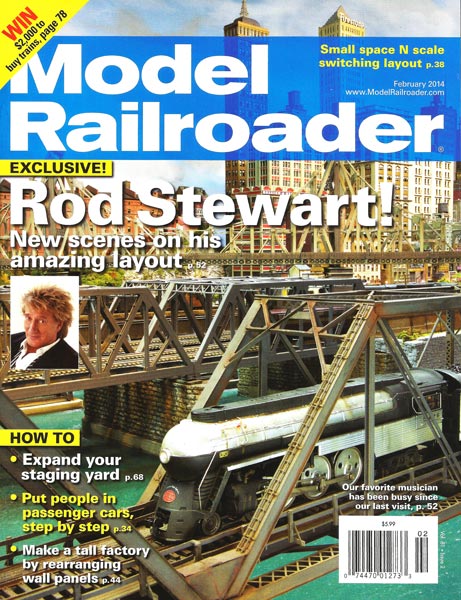

One example that comes to mind is one of the four covers on Rod Stewart’s layout I shot for Model Railroader, in particular the cover for the February 2014 issue. This is an example where I used several ideas from various Leslie Ragan paintings that he created depicting New York Central streamlined Hudsons at various points between New York and Chicago. There were a lot of cooler hues in his depictions of the Hudson’s so I thought that would be a great way to approach this cover. Admittedly I haven’t spent a lot of time in the eastern part of the United States. I’ve only been to up-state New York once in the autumn so I really needed to study that part of the country. Leslie Ragan was the perfect fit for this since he captured that area so well both in terms of trains and foliage. I think it worked quite nicely. For two of the other covers I borrowed colorization ideas from Griff Teller’s Pennsylvania Railroad calendar paintings. Teller’s works favored the warmer tones and so complemented the coolness of the other covers.

Edd – Who are other photographers that inspire and challenge you?

Steve – I’ve had the privilege to work with a lot of different photographers in my career, both as a lighting technician and when I managed my rental studio in Culver City, California. Each one of these gifted people had an area that he or she specialized in. I was constantly amused by their different approaches in solving problems and dealing with the unexpected issues that often occurred in producing photo shoots. These folks were the day to day shooters that provided a constant stream of images for their entertainment and corporate clientele. I think the one person that stands out in my mind that constantly came up with very creative portraiture concepts is David Strick. He has an impressive list of notable celebrities, scientist, actors and actresses that he’s worked with over the years and I have always admired his approach to shooting people. I’ve learned a lot from David and I’m grateful to have been able to work with him.

Other photographers that have had an influence on me and may be more familiar to readers of this list are Donald Duke, both for his photography skills and his publishing efforts of other authors work. Of course Richard Steinheimer has had a profound influence as well as Ted Benson; both were working professional photographers in their chosen fileds. But perhaps the guy I can most identify with is Lynn H. Westcott of Model Railroader magazine fame. I say this because Lynn had his feet firmly planted in both camps of railroad photography. He was a pioneering photographer in shooting model railroads and a very decent prototype shooter as well. I’m not much of a modeler anymore, so I wouldn’t want to challenge that aspect of his life. Lynn was truly a leader in model photography simply because he wanted good images to accompany his many books on the subject of modeling. I had several of Lynn’s books when I was starting my first layout. I’m sure he provided a lot of inspiration to countless modelers for, as near as I can figure, at least forty years!

One last mention I’d like to make with regards to influential photographers and that is of Margaret Bourke-White. I just think she was tremendously talented photographer at a time when it was difficult for anyone, men or women, to get the images she got. She sacrificed a lot in terms of her personal life and had a rather tragic ending at age sixty-seven. But she was one of the first photographers I became aware of as a child mostly due to the fact that my grandmother had a pile of old magazines at her home. My favorite thing was to plow through them and look at the old advertisements and photos. I think this was also the time I started to take notice of the photo credits and recall her as being one of the first names I became familiar with. Keeping track of photo credits became sort of a thing with me and eventually spilled over into railroad photography, Don Duke being one of the first names I recalled in that genre. To this day, with the images that I collect and research, I still believe it’s vitally important to give credit to the creative behind the work.

Edd – Over the years, I am sure you have had many interesting encounters trackside. Can you share a story about a particularly memorable experience?

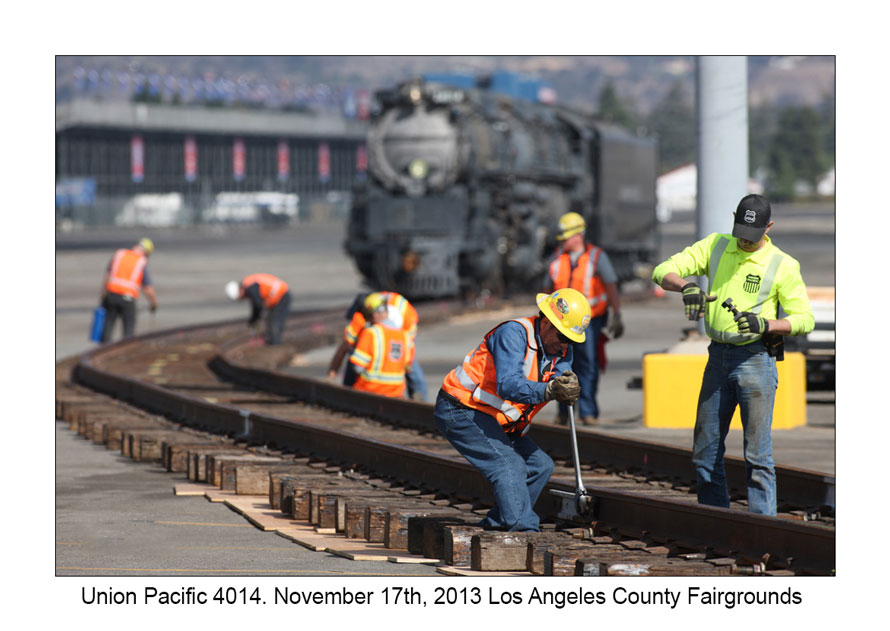

Steve – Oh God, there are so many! Perhaps my most recent and relevant recollection is the moving of Union Pacific’s Big Boy 4014 out of the Railgiants Museum at the Pomona Fairgounds here in California. As most of us know, the Union Pacific has re-acquired Big Boy 4014 for restoration to celebrate the sesquicentennial of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. Union Pacific chose the 4014 to restore her, hopefully in time for this event in 2019. The first hurdle was to get it ready to make the journey from Pomona, California to Cheyenne, Wyoming, a distance of 1100 miles by rail. Since this was taking place just a few miles away from my home, I spent months documenting the process which included rolling the locomotive across the parking lot to the Metrolink San Bernardino Line trackage, a distance of over a mile. This was done by using sections of panel track and rolling the engine over the short sections till it reached the end of the track. Sections of track that were behind the locomotive were disconnected and moved in front of the locomotive and it was pulled over the new section, slowly making its way toward the mainline. Eventually the day came when the tracks of the Metrolink line were cut and slid over to be connected to the temporary panel tracks that the 4014 was resting on. Finally, after fifty-two years of sitting in the park, she was back on the mainline. This was a pretty exciting moment for me and many other folks that were there that evening, I should mention that over 1000 people gathered at the Pomona Fairgrounds to see her roll back onto the main. I followed the procession all the way to the Union Pacific’s West Colton Yard in Bloomington, California. Eventually she made the journey to Cheyenne after several more months of preparation at West Colton. I followed her as far as Yermo, and turned back home. Other than the documentation work I’ve done with the ATSF 3751, this was probably the longest self-assigned project I’ve ever done and it really won’t be complete until 2019.

. . . you can’t expand your photographic skills by just shooting railroads.

Edd – It is always difficult to select a single “ favorite” from a body of work, but share with us a photo that is particularly meaningful to you or that has been important to your development as an artist, and tell us the story behind it.

Steve – I’d have to say that portraiture project I’m doing at the Nevada Northern Railway is the most meaningful body of work that I’m shooting at the moment. One likes to believe that whatever their pet project is presently, that somehow it represents an accumulation of all their knowledge and skill. I’d be happy with this summation in regards to this effort. I think in a larger sense, it’s me looking for a simpler way to shoot, although this type of portraiture is anything but easy. Perhaps what I mean to say is that I want to be able to satisfy my creative urges with the use of less equipment, and this style of shooting definitely fit that bill. I’d like to be able to expand this project to other steam preservation groups at some point. I did a group shot of 4014’s crew when they were in Pomona. I got off a good shot but it wasn’t done in this exact style. Maybe when they’re back in town in 2019 I can work out something to make that happen.

Edd – Do you have any new railroad related projects coming up?

Steve– Yes I do. I’m looking at two assignments in the near future for the BNSF railway, one here in California and another assignment in Arizona or New Mexico. I’m currently working on a video project that unfortunately I cannot speak much about right now but I promise it will be interesting when it is finally done, perhaps later this year. I’m working on a third and final Then & Now book for Arcadia Publishing on the Los Angeles Railway. At Golden West Books, we are continuing the publication of new monographs based on individuals’ experiences with the Pacific Electric Railway and the Los Angeles Railway. So far we have completed two titles on this subject with a third one in the works and it is being assembled at the designers right now. The first in the series is Alan Weeks’s remembrances of the PE through his remarkable black and white photography. Alan was about 14 years old when he started photographing the trolley systems of LA. Our second monograph is based on the photography of Jack L Whitmeyer, a local railfan who primarily documented the PE’s eastern part of the system from the late 1930’s till the 1960’s. The third monograph is by a gentleman by the name of Harvey Laner, a founding member of the Orange Empire Railway Museum at Perris, California. It will chronicle the transition between the demise of electric rail transportation in Los Angeles to its preservation at the museum. Harvey played a key role in starting the OERM and is founding member # 007. The book is due out in a few months and will be available on Amazon, as all of our monographs series are, as a print on demand book.

Edd – From your experience as a working photographer and railfan, what advice would you give a person, young or old, who is just starting out in railroad photography?

Steve – As discussed earlier, you can’t expand your photographic skills by just shooting railroads. Find additional subjects that interest you and photograph those subjects too. You will find that this will be mutually beneficial to everything you encounter.

Edd – For the last question, let me return to the “then and now” theme. If you could photograph a current location, and then be granted the wish to travel back in time to photograph the same location, what location would you choose for the “now” photos, and to what period of history would you travel for the “then” photos?

Steve – I think I would chose to witness a great victory on a battlefield or a great navel victory, something along the lines of the Battle of Midway or the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown. Another could be the sinking of the Spanish Armada by England in 1588. Any of these events or events with a similar weight in history would be absolutely breathtaking to witness! I suppose a “Now” photo of the South Pacific Ocean where the Battle of Midway took place wouldn’t exactly be a real showstopper, but it’s really the event that took place there that counts isn’t it.

Edd – Steve, it’s been great talking to you. Thanks again for sharing your work with us and I look forward to seeing where your photographic journey leads.

Steve – You’re welcome Edd! It’s been an enjoyable task trying encapsulate an entire career on paper! I hope we can visit again sometime.

Steve Crise – Photographs and text Copyright 2018.

Thank you Steve and Edd!

This is a great interview of someone who has been an influence on my work habits. The first I’ve heard of the NN day-and-a-half workshops with Mike Massee, who is another very accomplished photographer. You’ve peaked my interest; I feel the need to attend. I have attended a few of the NN winter weekends where Steve was leading the night photo shoots, his setup and execution is so well thought out. He makes it look easy. At the end of the evening even the most novice patron walks away with very compelling and intriguing images.

Steve’s attention to detail with his oil lamp and lantern series has taught me to look beyond the obvious and iconic; focus more on the subtleties in a scene. His portrait work, the gritty railroad workers against the plain white backdrop, has pushed me into the realm of the same type of imagery. I also appreciate his tasteful use with depth-of-field, using blur and sharpness to control where the viewer’s eye should land.

Matthew