Waking a steel horse from her slumber

The morning of July 16, I got up with the sunrise to the sounds of a local radio station’s morning show. The sun had not even risen above the horizon, but there were already some wispy clouds illuminated in a magenta color. I had no time to waste; I had an 8:00 a.m. rendezvous with my friend Ross Gochenaur at the Strasburg Railroad enginehouse. Ross has worked for the Strasburg Railroad for twenty years as an engineer, fireman, and shop worker. Today, however, I would get to observe and photograph the hostling of the engine pulling the railroad’s hourly train for the day.

Hostling of the engine is done by a hostler (today would be Ross’s day as hostler) who prepares an engine for the day’s duties before her crew arrives. Back in the era of steam, hostlers were a full time position which covered the overnight span when engines were not in use. At Strasburg, hostlers do not spend the night; instead, they spend the early morning hours with the engine. Some duties of hostlers include breaking the bank, dumping the ash, lubrication, the blowdown, and many others. Surprisingly, this long winded process takes only two hours on the long end to prepare a historic engine on “The Road to Paradise”.

When you walk through the door, it is as if you are transported back to the 1930’s when this was an everyday sight.

Before leaving, I packed a light lunch into my cooler not knowing how long my adventure may last, locked the door, and off I went. Heading through the northern Maryland farmlands and Pennsylvania Amish country, sunrise was absolutely stunning (and another adventure for me in the near future). As I crossed over the Susquehanna River on the Conowingo Dam, the famed eagles flew overhead through the mist of the open gates in search of a meal. As the blue sky began to show atop the haze filled Lancaster County farmlands I pulled into the lot at Strasburg.

After walking into the enginehouse at 7:58 a.m., I was greeted by Ross, Dave Lotfi, and Gabe Bocchino exchanging talk of their week ahead at the railroad. After reacquainting myself with the trio, Ross got to work with me following right behind. I was amazed at the atmosphere inside the enginehouse with mechanics working on the other two engines as Ross went about his work on our engine for the day. When you walk through the door, it is as if you are transported back to the 1930’s when this was an everyday sight. I thought, this is the epitome of steam railroading in the modern era. That is why I enjoy taking portraits of these men and women who are truly a part of history, and who live in a bygone era as their day job.

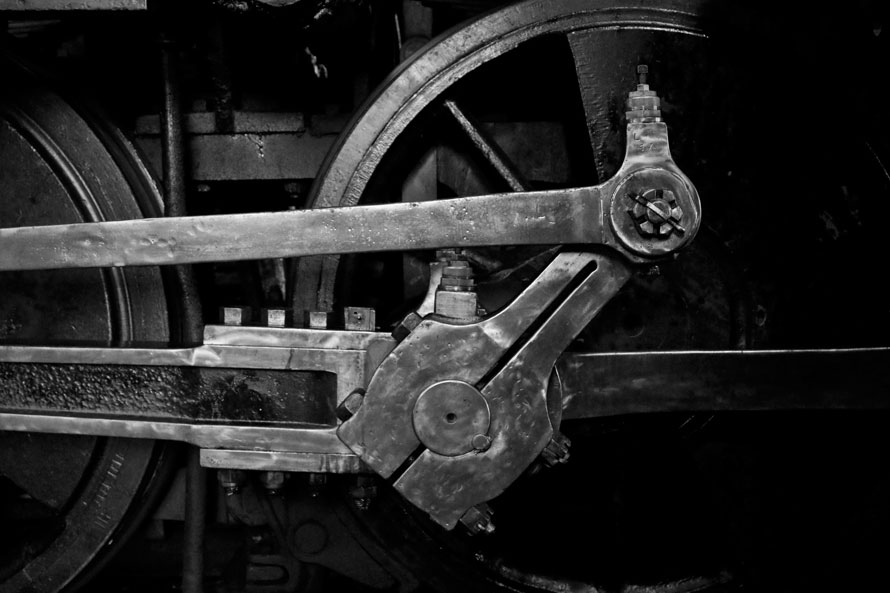

The locomotive Ross and I spent the morning on was the Norfolk and Western 475, a Mastodon class 4-8-0 (the same style as photographed by O. Winston Link on the famed Abingdon Branch) which ran on the Blacksburg Branch in Virginia. Ross familiarized me with some of the details, like the valve gear and how it varied from the other two engines that regularly run on the railroad. Strasburg acquired 475 in 1991, making it the “newest” steam locomotive on the railroad.

Ross began his day as hostler by topping off lubrication points on the engine with PB&J oil (Pin, Bearing, and Journal oil). The locomotive has points on the rods identical on both fireman and engineer side that number nearly ten per side on the rods alone, and with nearly 50 points in total from what I could tell on the locomotive as a whole. Once done with the PB&J, he used a forced grease pump to hit other points in the wheels and areas on the frame of the locomotive.

“How many ounces are there in a gallon, John?” Ross asked me. This information is needed to determine the amount of chemical agent to add to the tender to prevent a number of issues such as scale from occurring in the boiler.

I promptly replied, “I don’t know. I’m on summer vacation and you expect me to know that?”

We shared a good laugh and found another employee to steer us in the right direction (the answer is 128 ounces in a gallon). Afterwards, Ross climbed the tender ladder to dump the mix into the tender as the sun shone on his back and into the enginehouse.

Once he had gotten down from the tender, Ross climbed into the cab to see how much pressure the engine had from the day before and prepared to turn on the air compressor. I was forewarned about how the condensation from the compressor would shoot out. In an effort to keep my gear as dry as possible, I heeded the warning and moved next to the pilot truck of the engine so I could intentionally shoot towards the sun and let the condensation released catch the light. Ross got only a couple drops of water on him while he let the compressor fire the up rest of the way. After five minutes the compressor was running (no longer spewing condensation) and Ross was in the cab ready to back the engine to the coal loading bay.

Once we were stopped on his spot, Ross climbed down to fetch the front end loader and fill the tender. It took only four trips and some impressive aim to fill the tender for the eight round-trips to Paradise and back. If you ever photograph this event, I recommend bringing a cloth to wipe your lens, because it will get dusty. Next we backed up over the ash pit to dump all the previous day’s ash once the bank was broken up. Ross fetched the rake from the tender to smooth out the bank of coals that kept the engine warm overnight. Even this simple sounding task is very technical, needing to keep everything even and wake the fire up so it can be ready for new coals. He then shook the front grates and dumped the ash, and then the rear with a constant flow of water to make a slurry of the contents (this is also another very dusty event to photograph).

We made the run up the hill with the cylinder cocks open to run the engine rather hard to detect any issues.

As the pressure began to rise above the 120psi mark and the ash pans were closed, we backed to our last stop on the enginehouse lead right next to the newly expanded back shop. This is where all engines perform their constitutional daily blowdowns. A blowdown is initiated when the hostler pulls a lever leading to the bottom of the boiler which drains it and leads to the elimination of toxins from the boiler. Three ten second blowdowns are performed each morning before the engine gets run up the hill towards Fairview crossing, and back down the main towards the station. I joined Ross in the cab as he went out on the fireman’s side running board to pull the lever, while turning on other appliances on the engine like the dynamo. Through the fog I heard Ross call out to me jokingly, “Whew! That’ll clean out your pores.” I concurred as my arms became coated in sweat from the warm condensate cloud inside of the cab.

Finally, once all three blowdowns were complete and the pressure neared the operating pressure, we made the run up the hill with the cylinder cocks open to run the engine rather hard to detect any issues. No issues during today’s trip, so we drifted down the hill past the freight yard towards he station lead, where we brought the engine to a safe stop. Ross topped off the firebox with a couple scoops of coal and used some more PB&J oil on the running gear before handing the engine over to the crew for the day.

I thanked Ross for a great morning and the opportunity to photograph him and we parted ways. I stayed around and chatted with a few other railfans who had congregated around the engine. After chatting, I went back to the car and headed to a favorite spot of mine at the Red Caboose Motel to watch the train pass and have my lunch before heading home.

Johnathan Riley – Text and photographs Copyright 2018

This is a great article and I wondered if I might have your permission to republish this in the NMRA British Region magazine Roundhouse for the December 2018 issue?

Love this description of how a hostler wakes up a steam engine from its overnight slumber, ready to do another day’s work.

Thank you very much!

Enjoyed the article very much. My only thought was. You mentioned loading up with coal. but I don’t remember seeing anything about water.

Bruce, water is topped off in the tender before they put the engine to bed every day, so there is usually no need in the morning.

Great story! You forgot one thing, the word Hostler means keeper of horses, the only reason I know that Jonathan is from working with a bunch of Hostler’s in New Haven Ct many years ago. Beautiful pictures also.

Don’t know how my name did not appear 🙂

Thank you! The meaning of hostler is something O had not discovered yet. Thanks for sharing!

Jonathan, this is a fantastic article accompanied by equally as great photos. As a fellow fan of steam railroading I appreciate and applaud your talents to capture the experiences for others to enjoy; please continue to do so. The Strasburg Railroad is a well photographed venue, but it continually yields new and fresh views of vintage train operations. Hopefully I will see you there again soon – let’s shoot around together.

Matthew

Matthew, thank you so much for the compliment. This means a lot coming from someone I look so highly of in photography. I love the challenge of finding new angles anywhere I travel. Indeed we should shoot together very soon!