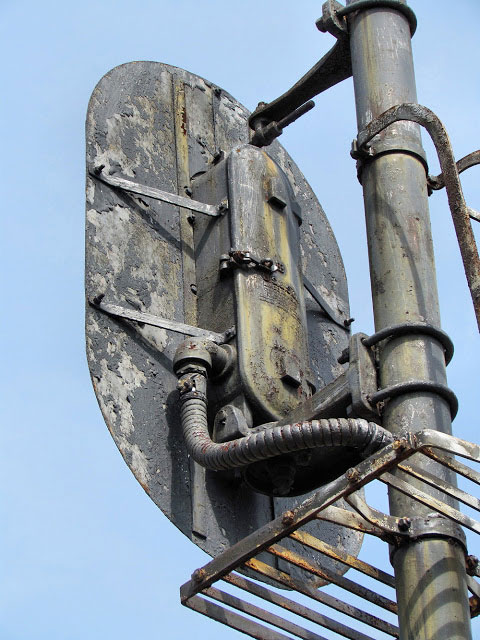

Lamenting the loss of a classic PRR signal—

The Position Light

Like many other essential railroad technologies, signaling developed with the need to manage the ever-increasing frequency of trains safely as railways expanded in the 19th century. As companies grew they adopted various solutions, but by the first quarter of the 20th century, standard designs began to evolve, and suppliers became valuable assets to the rail industry. Union Switch & Signal and General Railway Signal became two of the most common names in American signaling. They offered stock solutions that railroads could adopt and apply to their given network, but also catered to larger roads who sought to develop proprietary designs. The more recognizable wayside signaling was of course only a fraction of the full signal system. Behind the scenes, relay cases, code generators, interlocking towers, CTC machines and dispatching offices were all tethered to miles of cable and track circuits. This complex network communicated the vitally needed information to their endpoint – the signals, that familiar line-side icon of railroading as we know it. Read more